Shell Industries at Mohenjodaro Kenoyer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Herein After Termed As Gulf) Occupying an Area of 7300 Km2 Is Biologically One of the Most Productive and Diversified Habitats Along the West Coast of India

6. SUMMARY Gulf of Katchchh (herein after termed as Gulf) occupying an area of 7300 Km2 is biologically one of the most productive and diversified habitats along the west coast of India. The southern shore has numerous Islands and inlets which harbour vast areas of mangroves and coral reefs with living corals. The northern shore with numerous shoals and creeks also sustains large stretches of mangroves. A variety of marine wealth existing in the Gulf includes algae, mangroves, corals, sponges, molluscs, prawns, fishes, reptiles, birds and mammals. Industrial and other developments along the Gulf have accelerated in recent years and many industries make use of the Gulf either directly or indirectly. Hence, it is necessary that the existing and proposed developments are planned in an ecofriendly manner to maintain the high productivity and biodiversity of the Gulf region. In this context, Department of Ocean Development, Government of India is planning a strategy for management of the Gulf adopting the framework of Integrated Coastal and Marine Area Management (ICMAM) which is the most appropriate way to achieve the balance between the environment and development. The work has been awarded to National Institute of Oceanography (NIO), Goa. NIO engaged Vijayalakshmi R. Nair as a Consultant to compile and submit a report on the status of flora and fauna of the Gulf based on secondary data. The objective of this compilation is to (a) evolve baseline for marine flora and fauna of the Gulf based on secondary data (b) establish the prevailing biological characteristics for different segments of the Gulf at macrolevel and (c) assess the present biotic status of the Gulf. -

Convention on Migratory Species

CMS Distribution: General CONVENTION ON UNEP/CMS/COP11/Inf.21 MIGRATORY 16 July 2014 SPECIES Original: English 11th MEETING OF THE CONFERENCE OF THE PARTIES Quito, Ecuador, 4-9 November 2014 Agenda Item 23.3.1 ASSESSMENT OF GAPS AND NEEDS IN MIGRATORY MAMMALS CONSERVATION IN CENTRAL ASIA 1. In response to multiple mandates (notably Concerted and Cooperative Actions, Rec.8.23 and 9.1, Res.10.3 and 10.9), CMS has strengthened its work for the conservation of large mammals in the central Asian region and inter alia initiated a gap analysis and needs assessment, including status reports of prioritized central Asian migratory mammals to obtain a better picture of the situation in the region and to identify priorities for conservation. Range States and a large number of relevant experts were engaged in the process, and national stakeholder consultation meetings organized in several countries. 2. The Meeting Document along with the Executive Summary of the assessment is available as UNEP/CMS/COP11/Doc.23.3.1. For reasons of economy, documents are printed in a limited number, and will not be distributed at the Meeting. Delegates are requested to bring their copy to the meeting and not to request additional copies. UNEP/CMS/COP11/Inf.21 Assessment of gaps and needs in migratory mammal conservation in Central Asia Report prepared for the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS) and the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH. Financed by the Ecosystem Restoration in Central Asia (ERCA) component of the European Union Forest and Biodiversity Governance Including Environmental Monitoring Project (FLERMONECA). -

Status of Indian Wild Ass (Equus Hemionus Khur ) in the Little Rann of Kutch

PAPER ZOOS' PRINT JOURNAL 15(5): 253-256 STATUS OF INDIAN WILD ASS (EQUUS HEMIONUS KHUR) IN THE LITTLE RANN OF KUTCH H.S. Singh Director, GEER Foundation, Indroda Park, Gandhinagar, Gujarat 382009, India Abstract The Indian Wild Ass, Equus hemionus khur is found restricted to the Rann of Kutch in Gujarat and its surrounding areas. The population of the sub species is on the increase in the ninetees since the last debilitating effects of the drought in 1987. The numbers are slowly increasing to the carrying capacity of the area, towards the recommended numbers suggested in the IUCN Action Plan. The numbers of Wild Ass may reach 4000 by 2010AD, if current conditions prevail and there is no severe setback by droughts. However, the study on the status of the Wild Assess indicates that the increasing numbers may cause problems to the local inhabitants. The threats by the loss of habitat due to exotic plants, salt manufacturing activities, defence activites and cattle grazing may affect the population, which is also likely to get dispersed in the coming years to the adjacent Thar Desert areas in Rajasthan. The paper discusses the population trends of the WIld Ass over the years and its effects, as also the need for alternate measures of conservation. Key words Indian Wild Ass, population, distribution, status, migration, conservation, Wild Ass Sanctuary Introduction data collected during the period. The Rann, fringe area, Bets of The Little Rann of Kutch in Gujarat State in India is a unique the Sanctuary and Khadir Bet were surveyed during the study. -

Western: Desert Specials Forest Owlet Extension

India Western: Desert Specials 17th January to 29th January 2021 (13 days) Forest Owlet Extension 29th January to 31st January 2021 (4 days) Demoiselle Cranes by David Shackelford The wonderfully diverse nation of India is well-known for its verdant landscapes and the snow-capped Himalayas. It therefore surprises many people to learn that India is also blessed with some incredible deserts, and our tour showcases this much-underrated habitat by exploring some of India’s less RBL India - Western Desert Specials and Forest Owlet Extension Itinerary 2 frequented parks and reserves in the county’s dry, western parts. Desert National Park, Tal Chappar and the Great and Little Ranns of Kutch are amongst the most important of the protected areas of western India and we will visit all of them. We will also pay a visit to the more verdant Mt Abu along with an extension to the deciduous forests of Tansa Reserve. Along the way we are going to see some of the most threatened and rare birds not only of India but of the whole world. Species we are searching for include the Great Indian Bustard which sadly teeters on the brink of extinction, the almost equally rare White-browed Bush Chat, along with Indian Spotted Creeper, Yellow-eyed Pigeon, Green Avadavat, Sociable Lapwing, Macqueen’s Bustard, White-naped Tit, Marshall’s Iora, and for those doing the extension the recently rediscovered Forest Owlet. We also stand a great chance at picking up two of the more difficult monotypic families in the world, namely Crab-Plover and Grey Hypocolius. -

Gastropods Diversity in Thondaimanaru Lagoon (Class: Gastropoda), Northern Province, Sri Lanka

Journal of Geoscience and Environment Protection, 2021, 9, 21-30 https://www.scirp.org/journal/gep ISSN Online: 2327-4344 ISSN Print: 2327-4336 Gastropods Diversity in Thondaimanaru Lagoon (Class: Gastropoda), Northern Province, Sri Lanka Amarasinghe Arachchige Tiruni Nilundika Amarasinghe, Thampoe Eswaramohan, Raji Gnaneswaran Department of Zoology, Faculty of Science, University of Jaffna, Jaffna, Sri Lanka How to cite this paper: Amarasinghe, A. Abstract A. T. N., Eswaramohan, T., & Gnaneswa- ran, R. (2021). Gastropods Diversity in Thondaimanaru lagoon (TL) is one of the three lagoons in the Jaffna Penin- Thondaimanaru Lagoon (Class: Gastropo- sula, Sri Lanka. TL (N-9.819584, E-80.134086), which is 74.5 Km2. Fringing da), Northern Province, Sri Lanka. Journal these lagoons are mangroves, large tidal flats and salt marshes. The present of Geoscience and Environment Protection, 9, 21-30. study is carried out to assess the diversity of gastropods in the northern part https://doi.org/10.4236/gep.2021.93002 of the TL. The sampling of gastropods was performed by using quadrat me- thod from July 2015 to June 2016. Different sites were selected and rainfall Received: January 25, 2020 data, water temperature, salinity of the water and GPS values were collected. Accepted: March 9, 2021 Published: March 12, 2021 Collected gastropod shells were classified using standard taxonomic keys and their morphological as well as morphometrical characteristics were analyzed. Copyright © 2021 by author(s) and A total of 23 individual gastropods were identified from the lagoon which Scientific Research Publishing Inc. belongs to 21 genera of 15 families among them 11 gastropods were identified This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International up to species level. -

The Amazing Life in the Indian Desert

THE AMAZING LIFE IN THE INDIAN DESERT BY ISHWAR PRAKASH CENTRAL ARID ZONE RESEARCH INSTITUTE JODHPUR Printed June, 1977 Reprinted from Tbe Illustrated Weekly of India AnDual1975 CAZRI Monogra,pp No. 6 , I Publtshed by the Director, Central Arid Zone Research Institute, Jodhpur, and printed by B. R. Chowdhri, Press Manager at Hl!ryana Agricultural University Press, Hissar CONTENTS A Sorcerer's magic wand 2 The greenery is transient 3 Burst of colour 4 Grasses galore 5 Destruction of priceless teak 8 Exciting "night life" 8 Injectors of death 9 Desert symphony 11 The hallowed National Bird 12 The spectacular bustard 12 Flamingo city 13 Trigger-happy man 15 Sad fate of the lord of the jungle 16 17 Desert antelopes THE AMAZING LIFE IN THE INDIAN DESERT The Indian Desert is not an endless stretch of sand-dunes bereft of life or vegetation. During certain seasons it blooms with a colourful range of trees and grasses and abounds in an amazing variety of bird and animal life. This rich natural region must be saved from the over powering encroachment of man. To most of us, the word "desert" conjures up the vision of a vast, tree-less, undulating, buff expanse of sand, crisscrossed by caravans of heavily-robed nomads on camel-back. Perhaps the vision includes a lonely cactus plant here and the s~ull of some animal there and, perhaps a few mini-groves of date-palm, nourished by an artesian well, beckoning the tired traveller to rest awhile before riding off again to the horizon beyond. This vision is a projection of the reality of the Saharan or the Arabian deserts. -

A Taste of Africa

BIRDING OUT OF AFRICA: INDIA Gujarat A TASTE OF AFRICA ndia is a vast, sprawling country, teeming with people, but it also supports more than 1 200 bird species. Most birders visiting India for the first time do a Inorthern loop, centred on Bharatpur and the Himalayan foothills (see Nick Garbutt’s article in volume 9, number 4). While this offers a good cross-section of Indian birds, as well as the chance to chase tigers, African birders might consider cutting their teeth in the state of Gujarat, which has more in common with this continent than the rest of India. Peter Ryan reports on some of the region’s birding attractions. TEXT & PHOTOGRAPHS BY PETER RYAN 58 BIRDING INDIA AFRICA – BIRDS & BIRDING irthplace of Mahatma Gandhi, for viewing and photography. Indeed, I pakistan INDIA Gujarat lies north of Mumbai on frequently found myself comparing it to India’s north-west coast. At Ethiopia in this regard. The Jainist tradi- Great Rann Gujarat some 196 000 square kilometres, tion of jiv daya is similar to that of ubuntu, of Kutch State itB is half the size of Zimbabwe, yet com- but extends to wildlife as well as people. Little Rann prises only five per cent of India’s land Birds and other wildlife are part of local of Kutch Gulf of Kutch Ahmedabad area. It offers a wide range of habitats, culture, and Gujaratis take pleasure in Jamnagar Velavadar NP from verdant woodland in the southern sharing their land with thousands of mi- Porbandar hill country, where the annual rainfall grant birds. -

Shell Working Industries of the Indus Civilization: a Summary

PALEORIENT, vol. 1011· 1984 SHELL WORKING INDUSTRIES OF THE INDUS CIVILIZATION: A SUMMARY J. M. KENOYER ABSTRACT. - The production and use of marine shell objects during the Mature Indus Civilization (2500-1700 B.C.) is used as a framework within which to analyse developments in technology, regional variation and the stratification of socio-economic systems. Major species of marine mollusca used in the shell industry are discussed in detail and possible ancient shelt"source areas are identified. Variations in shell artifacts within and between various urban, rural and coastal sites are presented as evidence for specialized production, hierarchical internal trade networks and regional interaction spheres. On the basis of ethnographic continuities, general socio-ritual aspects of shell use are discussed. RESUME. - Production et utilisation d'objets confectionnes apartir de coqui//es marines pendant la periode harappeenne (2500-1700) servent ;ci de cadre a une analyse des developpements technolog;ques, des variations regionales et de la stratification des systemes socio-economiques. Les principales especes de mollusques marins utilises pour l'industrie sur coqui//age et leurs origines possibles soht identifiees. Les variations observees sur les objets en coqui//age a/'interieur des sites urbains, ruraux ou cotiers sont autant de preuves des differences existant tant dans la production specialisee que dans les reseaux d'echange hierarchises et dans l'interaction des spheres regionales. Certains aspects socio-rituels de l'utilisation des coqui//ages sont egalement discutes en prenant appui sur les donnees ethnographiques. INTRODUCfION undeciphered writing system. The presence of cer tain diagnostic artifacts in the neighboring regions of Afghanistan, the Persian Gulf, and Mesopotamia In recent years the Indus Civilization· of Pakistan indicates that the Indus peoples also had contacts and Western India has been the focus of important with other contemporaneous civilizations. -

Shelled Molluscs

Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS) Archimer http://www.ifremer.fr/docelec/ ©UNESCO-EOLSS Archive Institutionnelle de l’Ifremer Shelled Molluscs Berthou P.1, Poutiers J.M.2, Goulletquer P.1, Dao J.C.1 1 : Institut Français de Recherche pour l'Exploitation de la Mer, Plouzané, France 2 : Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris, France Abstract: Shelled molluscs are comprised of bivalves and gastropods. They are settled mainly on the continental shelf as benthic and sedentary animals due to their heavy protective shell. They can stand a wide range of environmental conditions. They are found in the whole trophic chain and are particle feeders, herbivorous, carnivorous, and predators. Exploited mollusc species are numerous. The main groups of gastropods are the whelks, conchs, abalones, tops, and turbans; and those of bivalve species are oysters, mussels, scallops, and clams. They are mainly used for food, but also for ornamental purposes, in shellcraft industries and jewelery. Consumed species are produced by fisheries and aquaculture, the latter representing 75% of the total 11.4 millions metric tons landed worldwide in 1996. Aquaculture, which mainly concerns bivalves (oysters, scallops, and mussels) relies on the simple techniques of producing juveniles, natural spat collection, and hatchery, and the fact that many species are planktivores. Keywords: bivalves, gastropods, fisheries, aquaculture, biology, fishing gears, management To cite this chapter Berthou P., Poutiers J.M., Goulletquer P., Dao J.C., SHELLED MOLLUSCS, in FISHERIES AND AQUACULTURE, from Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS), Developed under the Auspices of the UNESCO, Eolss Publishers, Oxford ,UK, [http://www.eolss.net] 1 1. -

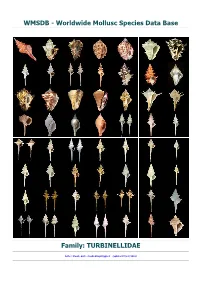

Turbinellidae

WMSDB - Worldwide Mollusc Species Data Base Family: TURBINELLIDAE Author: Claudio Galli - [email protected] (updated 07/set/2015) Class: GASTROPODA --- Clade: CAENOGASTROPODA-HYPSOGASTROPODA-NEOGASTROPODA-MURICOIDEA ------ Family: TURBINELLIDAE Swainson, 1835 (Sea) - Alphabetic order - when first name is in bold the species has images Taxa=276, Genus=12, Subgenus=4, Species=91, Subspecies=13, Synonyms=155, Images=87 aapta , Coluzea aapta M.G. Harasewych, 1986 acuminata, Turbinella acuminata L.C. Kiener, 1840 - syn of: Latirus acuminatus (L.C. Kiener, 1840) aequilonius, Fulgurofusus aequilonius A.V. Sysoev, 2000 agrestis, Turbinella agrestis H.E. Anton, 1838 - syn of: Nicema subrostrata (J.E. Gray, 1839) aldridgei , Vasum aldridgei G.W. Nowell-Usticke, 1969 - syn of: Attiliosa aldridgei (G.W. Nowell-Usticke, 1969) altocanalis , Coluzea altocanalis R.K. Dell, 1956 amaliae , Turbinella amaliae H.C. Küster & W. Kobelt, 1874 - syn of: Hemipolygona amaliae (H.C. Küster & W. Kobelt, 1874) angularis , Coluzea angularis (K.H. Barnard, 1959) angularis , Turbinella angularis L.A. Reeve, 1847 - syn of: Leucozonia nassa (J.F. Gmelin, 1791) angularis riiseana , Turbinella angularis riiseana H.C. Küster & W. Kobelt, 1874 - syn of: Leucozonia nassa (J.F. Gmelin, 1791) angulata , Turbinella angulata (J. Lightfoot, 1786) annulata, Syrinx annulata P.F. Röding, 1798 - syn of: Pustulatirus annulatus (P.F. Röding, 1798) aptos , Columbarium aptos M.G. Harasewych, 1986 - syn of: Coluzea aapta M.G. Harasewych, 1986 ardeola , Vasum ardeola A. Valenciennes, 1832 - syn of: Vasum caestus (W.J. Broderip, 1833) armatum , Vasum armatum (W.J. Broderip, 1833) armigera , Tudivasum armigera A. Adams, 1855 - syn of: Tudivasum armigerum (A. Adams, 1856) armigera , Turbinella armigera J.B.P.A. -

Proceedings of the United States National Museum

a Proceedings of the United States National Museum SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION • WASHINGTON, D.C. Volume 121 1967 Number 3579 VALID ZOOLOGICAL NAMES OF THE PORTLAND CATALOGUE By Harald a. Rehder Research Curator, Division of Mollusks Introduction An outstanding patroness of the arts and sciences in eighteenth- century England was Lady Margaret Cavendish Bentinck, Duchess of Portland, wife of William, Second Duke of Portland. At Bulstrode in Buckinghamshire, magnificent summer residence of the Dukes of Portland, and in her London house in Whitehall, Lady Margaret— widow for the last 23 years of her life— entertained gentlemen in- terested in her extensive collection of natural history and objets d'art. Among these visitors were Sir Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander, pupil of Linnaeus. As her own particular interest was in conchology, she received from both of these men many specimens of shells gathered on Captain Cook's voyages. Apparently Solander spent considerable time working on the conchological collection, for his manuscript on descriptions of new shells was based largely on the "Portland Museum." When Lady Margaret died in 1785, her "Museum" was sold at auction. The task of preparing the collection for sale and compiling the sales catalogue fell to the Reverend John Lightfoot (1735-1788). For many years librarian and chaplain to the Duchess and scientif- 1 2 PROCEEDINGS OF THE NATIONAL MUSEUM vol. 121 ically inclined with a special leaning toward botany and conchology, he was well acquainted with the collection. It is not surprising he went to considerable trouble to give names and figure references to so many of the mollusks and other invertebrates that he listed. -

Elixir Journal

46093 Nilesh S. Chavan and Rahul N. Jadhav / Elixir Appl. Zoology 105C (2017) 46093-46099 Available online at www.elixirpublishers.com (Elixir International Journal) Applied Zoology Elixir Appl. Zoology 105C (2017) 46093-46099 Survey of Marine Molluscan diversity along the coasts of Shreewardhan (M.S.) Nilesh S. Chavan1 and Rahul N. Jadhav2 Department of Zoology, G.E.Society’s Arts, Commerce & Science College, Shreewardhan-402110,Dist.- Raigad. Department of Zoology, Vidyavardhini’s College of Arts, Commerce and Science, Vasai (W), Maharashtra 401202,India. ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: The preliminary survey of marine molluscs at 5 coasts of Shreewardhan namely Received: 23 February 2017; Shreewardhan coast, Shekhadi coast, Dive Agar coast, Sarva coast and Harihareshwar Received in revised form: coast were carried out. The occurrence of 65 species belonging to 52 genera, 35 families, 29 March 2017; 8 orders and 3 classes was noted. The Class- Gastropoda was diverse and represented by Accepted: 4 April 2017; 3 orders, 24 families, 32 genera and 42 species. Class- Scaphopoda was represented by single order, family, genus and species whereas Class- Bivalvia was represented by Keywords 4orders, 10 families, 19 genera and 22 species of molluscs. Among these 65% of the Marine, species are gastropods, 34% are bivalvia and only 1% is Scaphopoda were noted. The Molluscs, present survey indicates that Sarva coast and Shekhadi coast are diversity rich followed Diversity, by Shreewardhan coast, Harihareshwar coast and Dive Agar coast as far as molluscan Shreewardhan coasts. diversity is concerned. © 2017 Elixir All rights reserved. Introduction Sea shells play an important role in geological as well as Area of Research biological processes (Soni and Thakur,2015).