The 2016 Mayoral Elections in London Timothy Whitton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Democratic Audit: What Does Boris Johnson's Political Record Tell Us

Democratic Audit: What does Boris Johnson’s political record tell us about his prospects as Prime Minister? Page 1 of 3 What does Boris Johnson’s political record tell us about his prospects as Prime Minister? As Conservative MPs whittle the contest to be next leader of the party – and so next Prime Minister – down to a final two who will face the party membership, Ben Worthy assesses the record of the clear frontrunner, Boris Johnson, and what his time as London Mayor and Foreign Secretary indicate about his aptitude for the top job. Boris Johnson speaking to Foreign Office staff, 14 July 2016. Picture: Foreign and Commonwealth Office/ (CC BY 2.0) licence ‘Prime Minister Boris Johnson’: I know, as I write those words, what you have all just thought, said or shouted aloud. His performance in the five-way BBC debate filled no one with confidence. But we need to take care with our snap judgements. Many Prime Ministers were viewed very differently before their arrival in power. Churchill was seen as a reckless war-monger, and Thatcher a temporary female stop-gap. Remember too that Theresa May, and before her Gordon Brown, were to be diligent, strong, decisive leaders. Clement Attlee’s limerick about his own life says it all. To measure leaders, we need to understand both the person and the context. To take the person of ‘Boris’ first, Johnson’s own time in high office leaves us with some pretty mixed messages as to how he would be in Number 10. As Rafael Behr points out, we have a selection of different Boris’s to choose from. -

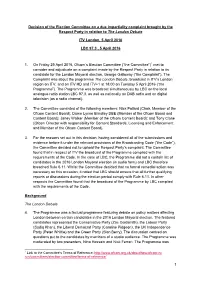

1 Decision of the Election Committee on a Due Impartiality Complaint Brought by the Respect Party in Relation to the London Deba

Decision of the Election Committee on a due impartiality complaint brought by the Respect Party in relation to The London Debate ITV London, 5 April 2016 LBC 97.3 , 5 April 2016 1. On Friday 29 April 2016, Ofcom’s Election Committee (“the Committee”)1 met to consider and adjudicate on a complaint made by the Respect Party in relation to its candidate for the London Mayoral election, George Galloway (“the Complaint”). The Complaint was about the programme The London Debate, broadcast in ITV’s London region on ITV, and on ITV HD and ITV+1 at 18:00 on Tuesday 5 April 2016 (“the Programme”). The Programme was broadcast simultaneously by LBC on the local analogue radio station LBC 97.3, as well as nationally on DAB radio and on digital television (as a radio channel). 2. The Committee consisted of the following members: Nick Pollard (Chair, Member of the Ofcom Content Board); Dame Lynne Brindley DBE (Member of the Ofcom Board and Content Board); Janey Walker (Member of the Ofcom Content Board); and Tony Close (Ofcom Director with responsibility for Content Standards, Licensing and Enforcement and Member of the Ofcom Content Board). 3. For the reasons set out in this decision, having considered all of the submissions and evidence before it under the relevant provisions of the Broadcasting Code (“the Code”), the Committee decided not to uphold the Respect Party’s complaint. The Committee found that in respect of ITV the broadcast of the Programme complied with the requirements of the Code. In the case of LBC, the Programme did not a contain list of candidates in the 2016 London Mayoral election (in audio form) and LBC therefore breached Rule 6.11. -

(CAL) Calls for Caroline Spelman MP to Be Held

19 March 2012 ‘Clean Air in London’ (CAL) calls for Caroline Spelman MP to be held accountable and resign for the UK misleading the European Commission (Commission) over its Plans and Programmes for nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and other serious public health failings Commission will be asking the UK authorities to comment on CAL’s claim that the UK unlawfully obtained a time extension until 2011 to comply with the PM10 daily limit value in London because the public was not consulted on time on the updated air quality plan UK set to be fast-tracked to the Court of Justice of the European Union if breaches of PM10 air quality laws are confirmed in London i.e. just two steps short of £300m per annum fines Three cheers for Jean Lambert MEP, Keith Taylor MEP, Darren Johnson AM, Jenny Jones AM, Caroline Lucas MP and the Green Party for their effective teamwork and action to protect public health. We now need others to act urgently Clean Air in London (CAL) lodged a formal complaint in two parts with the European Commission (Commission) on 15 January 2012 over the UK’s failure to comply with air quality laws in London and elsewhere (the Complaint). Details can be seen at: http://cleanairinlondon.org/legal/clean-air-in-london-lodges-complaint-over-breaches-of-air-pollution- laws-in-london/ Jean Lambert and Keith Taylor, Green Party MEPs for London and the South East of England, wrote to Commissioner Potočnik, European Commissioner for the Environment, in support of CAL’s Complaint and have now received a formal response. -

Leisure Opportunities 6Th September 2016 Issue

Find great staffTM leisure opportunities 6 - 19 SEPTEMBER 2016 ISSUE 692 Daily news & jobs: www.leisureopportunities.co.uk DW Sports moves for Fitness First clubs The long-running saga of the south – particularly London – a sale of Fitness First’s UK clubs successful deal would see the UK’s looks to be in its final act, as up second largest health club chain to five operators are understood boast an enviable spread of sites. to have completed separate The former Wigan Athletic deals to buy out the nearly chair also said he “wasn’t 70-strong portfolio – with DW expecting any trouble from the Sports leading the way. competition people” in terms of The deals, expected to be the deal, with the geographical confirmed by Fitness First differences between DW Sports owner Oaktree Capital later and Fitness First reducing the this month, will see Fitness likelihood of intense scrutiny First carved up by DW Sports, from the Competition and The Gym Group and GLL Markets Authority (CMA), (Greenwich Leisure Ltd) – which previously proved the while other firms are circling. downfall of a proposed merger DW Sports, owned by between Pure Gym and The multimillionaire Dave Whelan, Gym Group. is expected to pick up a total of Whelan is optimistic the move would not be scuppered by competition authorities If the deal goes through, it 63 clubs, nearly doubling its will immediately make DW existing number of clubs operated under the have so much of a presence” in an interview Sports – which has around 80 sites – one DW Fitness banner. with the Wigan Evening Post. -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

Thursday Volume 506 25 February 2010 No. 45 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Thursday 25 February 2010 £5·00 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2010 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Parliamentary Click-Use Licence, available online through the Office of Public Sector Information website at www.opsi.gov.uk/click-use/ Enquiries to the Office of Public Sector Information, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 4DU; e-mail: [email protected] 427 25 FEBRUARY 2010 428 Dr. Alan Whitehead (Southampton, Test) (Lab): Does House of Commons my hon. Friend accept that a large element of fuel poverty relates to the energy efficiency of the homes in Thursday 25 February 2010 which fuel-poor people live? Does he also accept that efforts to ensure that those homes are made properly energy efficient are a vital part of our attack on fuel The House met at half-past Ten o’clock poverty? What is his assessment of the likely impact of community energy response teams, community energy saving programmes, and other schemes, such as the PRAYERS Great British Refurb, on improving the energy efficiency of homes? [MR.SPEAKER in the Chair] Mr. Kidney: I agree that the most sustainable way of BUSINESS BEFORE QUESTIONS helping people to stay out of fuel poverty is to ensure that their homes are energy efficient. That is why we have concentrated so much on the energy companies’ LONDON LOCAL AUTHORITIES BILL [LORDS] obligation, under which more than 6 million homes (BY ORDER) have been insulated. Another 2 million have been insulated Second Reading opposed and deferred until Thursday under Warm Front. -

Department of English and American Studies UKIP And

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Anders Heger UKIP and British Politics Bachelor‟s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Stephen Paul Hardy, Ph.D. 2015 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. ..................................................... Author‟s signature Acknowledgement I would like to express my thanks towards the Masaryk University and the Czech Republic for providing me with free education and I would also like to thank my supervisor, Mr. Hardy, for his support and much appreciated counsel. Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 5 The History of UKIP ..................................................................................................................... 8 Allan Sked and the First Years .................................................................................................. 8 Change of Leadership and Becoming the Fourth Largest Party ............................................. 12 Becoming a Political Party ...................................................................................................... 16 The Beginning of a New Era ................................................................................................... 21 Analysing the Party‟s Policies ................................................................................................... -

Number of Votes Recorded Rathy ALAGARATNAM UK Independence

GLA 2016 ELECTIONS ELECTION OF A CONSTITUENCY MEMBER OF THE LONDON ASSEMBLY RESULTS Constituency Brent & Harrow Declaration of Results of Poll I hereby give notice as Constituency Returning Officer at the election of a constituency member of the London Assembly for the Brent & Harrow constituency held on 5 May 2016 that the number of votes recorded at the election is as follows: - Name of Candidates Name of Registered Political Party (if any) Number of Votes Recorded Rathy ALAGARATNAM UK Independence Party (UKIP) 9074 Joel Erne DAVIDSON The Conservative Party Candidate 59147 Anton GEORGIOU London Liberal Democrats 11534 Jafar HASSAN Green Party 9874 Akib MAHMOOD Respect (George Galloway) 5170 Navin SHAH Labour Party 79902 The number of ballot papers rejected was as follows:- (a) Unmarked 1814 (b) Uncertain 107 (c) Voting for too many 569 (d) Writing identifying voter 14 (e) Want of official mark 2 Total 2506 And I do hereby declare the said Navin SHAH, Labour Party is duly elected as constituency member of the Greater London Authority for the said constituency. Signed - Constituency Returning Officer Carolyn Downs Page 1 of 1 Generated On: 13/05/2016 12:27:25 Final Results GLA 2016 ELECTIONS CONSTITUENCY MEMBER OF THE LONDON ASSEMBLY RESULTS Constituency Brent & Harrow Total number of ballot papers counted 177207 Name of Candidates Name of Registered Political Party Number of Votes Recorded (if any) Rathy ALAGARATNAM UK Independence Party (UKIP) 9074 Joel Erne DAVIDSON The Conservative Party Candidate 59147 Anton GEORGIOU London Liberal -

Anti-Zionism and Antisemitism Cosmopolitan Reflections

Anti-Zionism and Antisemitism Cosmopolitan Reflections David Hirsh Department of Sociology, Goldsmiths, University of London, New Cross, London SE14 6NW, UK The Working Papers Series is intended to initiate discussion, debate and discourse on a wide variety of issues as it pertains to the analysis of antisemitism, and to further the study of this subject matter. Please feel free to submit papers to the ISGAP working paper series. Contact the ISGAP Coordinator or the Editor of the Working Paper Series, Charles Asher Small. Working Paper Hirsh 2007 ISSN: 1940-610X © Institute for the Study of Global Antisemitism and Policy ISGAP 165 East 56th Street, Second floor New York, NY 10022 United States Office Telephone: 212-230-1840 www.isgap.org ABSTRACT This paper aims to disentangle the difficult relationship between anti-Zionism and antisemitism. On one side, antisemitism appears as a pressing contemporary problem, intimately connected to an intensification of hostility to Israel. Opposing accounts downplay the fact of antisemitism and tend to treat the charge as an instrumental attempt to de-legitimize criticism of Israel. I address the central relationship both conceptually and through a number of empirical case studies which lie in the disputed territory between criticism and demonization. The paper focuses on current debates in the British public sphere and in particular on the campaign to boycott Israeli academia. Sociologically the paper seeks to develop a cosmopolitan framework to confront the methodological nationalism of both Zionism and anti-Zionism. It does not assume that exaggerated hostility to Israel is caused by underlying antisemitism but it explores the possibility that antisemitism may be an effect even of some antiracist forms of anti- Zionism. -

Revue Française De Civilisation Britannique, XV-4 | 2010 All ‘Kens’ to All Men

Revue Française de Civilisation Britannique French Journal of British Studies XV-4 | 2010 Présentations, re-présentations, représentations All ‘Kens’ to all Men. Ken the Chameleon: reinvention and representation, from the GLC to the GLA À chacun son « Ken ». Ken le caméléon: réinvention et représentation, du Greater London Council à la Greater London Authority Timothy Whitton Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/rfcb/6151 ISSN: 2429-4373 Publisher CRECIB - Centre de recherche et d'études en civilisation britannique Printed version Date of publication: 1 June 2010 ISSN: 0248-9015 Electronic reference Timothy Whitton, “All ‘Kens’ to all Men. Ken the Chameleon: reinvention and representation, from the GLC to the GLA”, Revue Française de Civilisation Britannique [Online], XV-4 | 2010, Online since 01 June 2010, connection on 07 January 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/rfcb/6151 This text was automatically generated on 7 January 2021. Revue française de civilisation britannique est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. All ‘Kens’ to all Men. Ken the Chameleon: reinvention and representation, fro... 1 All ‘Kens’ to all Men. Ken the Chameleon: reinvention and representation, from the GLC to the GLA À chacun son « Ken ». Ken le caméléon: réinvention et représentation, du Greater London Council à la Greater London Authority Timothy Whitton 1 Ken Livingstone’s last two official biographies speak volumes about the sort of politician he comes across as being. John Carvel’s title1 is slightly ambiguous and can be interpreted in a variety of ways: Turn Again Livingstone suggests that the one time leader of the Greater London Council (GLC) and twice elected mayor of London shows great skill in steering himself out of any tight corners he gets trapped in. -

European Parliament Elections 2014

European Parliament Elections 2014 Updated 12 March 2014 Overview of Candidates in the United Kingdom Contents 1.0 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 2 2.0 CANDIDATE SELECTION PROCESS ............................................................................................. 2 3.0 EUROPEAN ELECTIONS: VOTING METHOD IN THE UK ................................................................ 3 4.0 PRELIMINARY OVERVIEW OF CANDIDATES BY UK CONSTITUENCY ............................................ 3 5.0 ANNEX: LIST OF SITTING UK MEMBERS OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT ................................ 16 6.0 ABOUT US ............................................................................................................................. 17 All images used in this briefing are © Barryob / Wikimedia Commons / CC-BY-SA-3.0 / GFDL © DeHavilland EU Ltd 2014. All rights reserved. 1 | 18 European Parliament Elections 2014 1.0 Introduction This briefing is part of DeHavilland EU’s Foresight Report series on the 2014 European elections and provides a preliminary overview of the candidates standing in the UK for election to the European Parliament in 2014. In the United Kingdom, the election for the country’s 73 Members of the European Parliament will be held on Thursday 22 May 2014. The elections come at a crucial junction for UK-EU relations, and are likely to have far-reaching consequences for the UK’s relationship with the rest of Europe: a surge in support for the UK Independence Party (UKIP) could lead to a Britain that is increasingly dis-engaged from the EU policy-making process. In parallel, the current UK Government is also conducting a review of the EU’s powers and Prime Minister David Cameron has repeatedly pushed for a ‘repatriation’ of powers from the European to the national level. These long-term political developments aside, the elections will also have more direct and tangible consequences. -

Routes 289 and 455 Consultation Report July 2017

Consultation on proposed changes to bus routes 289 and 455 Consultation Report July 2017 Contents Executive summary ..................................................................................................... 4 Summary of issues raised during consultation ......................................................... 4 Next steps ................................................................................................................ 4 1. About the proposals ............................................................................................ 5 1.1 Introduction .................................................................................................... 5 1.2 Purpose .......................................................................................................... 5 1.3 Detailed description ........................................................................................ 5 2. About the consultation ........................................................................................ 7 2.1 Purpose .......................................................................................................... 7 2.2 Potential outcomes ......................................................................................... 7 2.4 Who we consulted .......................................................................................... 7 2.5 Dates and duration ......................................................................................... 7 2.6 What we asked .............................................................................................. -

Icm Research Job No (1-6) 960416

ICM RESEARCH JOB NO (1-6) KNIGHTON HOUSE 56 MORTIMER STREET SERIAL NO (7-10) LONDON W1N 7DG TEL: 0171-436-3114 CARD NO (11) 1 2004 LONDON ELECTIONS QUESTIONNAIRE INTRODUCTION: Good morning/afternoon. I am ⇒ IF NO 2ND CHOICE SAY: from ICM, the independent opinion research Q7 So can I confirm, you only marked one company. We are conducting a survey in this area choice in the London Assembly election? today and I would be grateful if you could help by (14) answering a few questions … Yes 1 No 2 ⇒ CHECK QUOTAS AND CONTINUE IF ON Don’t know 3 QUOTA Q1 First of all, in the recent election for the ***TAKE BACK THE BALLOT PAPERS*** new London Mayor and Assembly many people were not able to go and vote. Can you tell me, did ♦ SHOW CARD Q8 you manage to go to the polling station and cast Q8 When you were voting in the elections for your vote? the London Assembly and London Mayor, what (12) was most important to you? Of the following Yes 1 possible answers, can you let me know which were No 2 the two most important as far as you were Don’t know 3 concerned (15) ⇒ IF NO/DON’T KNOW, GO TO Q9 Q2 Here is a version of the ballot paper like the These elections were a chance to let one used for the MAYOR ELECTION. the national government know what 1 (INTERVIEWER: HAND TO RESPONDENT). Could you think about national issues you please mark with an X who you voted for as I felt it was my duty to vote 2 your FIRST choice as London Mayor? MAKE SURE Choosing the best people to run 3 RESPONDENT MARKS BALLOT PAPER IN London CORRECT COLUMN I wanted to support a particular party 4 I wanted to let the government know Q3 And could you mark with an X who you my view on the Iraq war 5 voted for as your SECOND choice? ? MAKE SURE RESPONDENT MARKS BALLOT PAPER IN ⇒ VOTERS SKIP TO Q16 CORRECT COLUMN Q9 Here is a version of the ballot paper like the ND one used for the MAYOR ELECTION.