'Colored' Orphan Asylums in Virginia, 1867–1930

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maryland Historical Magazine

)- i-5 5o Maryland 2 3 0. Historical Magazine 0 3. iE. CO 00 2 0 D. 3 Published Quarterly by the Museum and Library of Maryland History Maryland Historical Society Spring 1993 THE MARYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY OFFICERS AND BOARD OF TRUSTEES, 1992-93 L. Patrick Deering, Chairman Jack S. Griswold, President Dorothy Mcllvain Scott, Vice President Bryson L. Cook, Counsel A. MacDonough Plant, Secretary William R. Amos, Treasurer Term expires 1993 Term Expires 1996 Clarence W. Blount Gary Black, Jr. E. Phillips Hathaway Louis G. Hecht Charles McC Mathias J. Jefferson Miller II Walter D. Pinkard, Sr. Howard R. Rawlings Orwin C. Talbott Jacques T Schlenger David Mel. Williams Trustees Representing Baltimore City and Counties Term Expires 1994 Baltimore City, Kurt L. Schmoke (Ex Officio) Forrest F. Bramble, Jr. Allegany Co.,J. Glenn Bealljr. (1993) Stiles T. Colwill Anne Arundel Co., Robert R. Neall (Ex Officio) George D. Edwards II Baltimore Co., Roger B. Hayden (Ex Officio) Bryden B. Hyde Calvert Co., Louis L. Goldstein (1995) Stanard T. Klinefelter Carroll Co., William B. Dulany (1995) Mrs. Timothy E. Parker Frederick Co., Richard R. Kline (1996) Richard H. Randall, Jr. Harford Co., Mignon Cameron (1995) Truman T Semans Kent Co., J. Hurst Purnell, Jr. (1995) M. David Testa Montgomery Co., George R. Tydings (1995) H. Mebane Turner Prince George's Co., John W Mitchell (1995) Term Expires 1995 Washington Co., E. Mason Hendrickson (1993) James C. Alban III Worcester Co., Mrs. Brice Phillips (1995) H. Furlong Baldwin Chairman Emeritus P. McEvoy Cromwell Samuel Hopkins Benjamin H. Griswold III J. Fife Symington, Jr. -

Women's Suffrage and Citizenship Marker

Women’s Suffrage and Citizenship Marker Blurbs 1. Sen. Arcada Stark Balz: JOHNSON, MARION, MONROE COs.—Bloomington native Arcada Stark Balz grew up in Indianapolis, where she attended Normal College. In the 1930s, she served as president of the Indiana Federation of Women’s Clubs and director of the General Federation of Women’s Clubs. In her club work, she delivered speeches encouraging women to get involved in policy making and advised on the Indiana club’s legislative department. Balz became the first woman to serve in the Indiana Senate when voters elected her to office in 1942; she was reelected in 1944. As a representative of Marion and Johnson Counties, the Republican Senator authored legislation to eliminate neglect and abuse in nursing homes. Sen. Balz also served as chairman of the Postwar Planning Committee in World War II. 2. Carrie Barnes: MARION CO.—African American public school teacher Carrie Barnes served as president of Branch No. 7 of the Equal Suffrage Association of Indiana (ESA) in 1912. Of the branch’s work, Barnes proclaimed “We all feel that colored women have need for the ballot that white women have, and a great many needs that they have not.” While branch president and later as president of the Women’s Council, she spearheaded local black suffrage work, collaborating with white branches and trade unions to obtain the right to vote. 3. Virginia Brooks: LAKE CO., IN, COOK CO., IL—Dubbed the “Joan of Arc” of West Hammond, social reformer Virginia Brooks organized for suffrage in the Calumet Region. Determined to end the mistreatment of immigrants and expel corrupt politicians from West Hammond (now Calumet City)—an Illinois town that overlapped into Indiana—she delivered speeches in barrooms, confronted law enforcement officials, and founded her own publication. -

Black Vote Remains Crucial "I'm an Atheist and I'd Go to by D

AUGUST 2016 HEALTH WELLNESS & NUTRITION SUPPLEMENT EYE HEALTH AND IMMUNIZATION VOL. 51, NO. 44 • AUGUST 11 - 17, 2016 PRESENTED BY WI Health SupplementSPONSORS Pressure Leads to Councilman Orange’s Early Resignation - Hot Topics, Page 4 Center Section Rev. Barber First Day of Moving Forward, School Comes Before and After Early for Some DNC Convention D.C. Students By William J. Ford WI Staff Writer @jabariwill A pep-rally atmosphere greet- ed students and parents Mon- day, Aug. 8 at Turner Elementary School in southeast D.C. to begin the first day of school — a day that came a full two weeks earlier than for most of the city. Turner is one of 10 city schools taking part in the District's ex- 5Rev. William Barber II / Photo tended-school year, in which 20 by Shevry Lassiter extra days have been added for By Stacy M. Brown schools with at least 55 percent WI Senior Writer of its students not fully meeting expectations on the English and The headlines blared almost non- math portions of standardized as- stop. sessment tests in the 2014-2015 "Rev. William Barber Rattles the academic year. Windows, Shakes the DNC Walls," During that year, Turner had one of the lowest rankings among NBC News said. 5Turner Elementary School Principal Eric Bethel greets a student on Aug. 8, the first day of the extended school year for D.C. "The Rev. William Barber public schools. Turner is one of 10 schools to partake in the program to boost student achievement. / Photo by William J. Ford DCPS Page 8 dropped the mic," The Washington Post marveled. -

July 22, 1983, Dear Mr. Mcdaniel

- .. THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON July 22, 1983, Dear Mr. McDaniel: I want to thank you for sending a copy of Building on Yesterday, Becoming To morrow: The Washington Hospital Center's First 25 Years to Mr. Deaver for his perusal. He is traveling out of the country at present, but I know that he will enjoy looking at it upon his return. Again, thank you for your thoughtfulness. Sincerely, Donna L. Blume Staff Assistant to Michael K. Deaver Mr. John McDaniel President The Washington Hospital Center 110 Irving Street, N.W. Washington, D. C. 20010 [ I THE WASHINGTON HOSPITAL CENTER II II II II July 14, 1983 Michael K. Deaver Deputy Chief of Staff Asst. to President 1600 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W. Washington, D.C. 20500 Dear Mr. Deaver: Enclosed you will find a copy of Building on Yesterday, Becoming Tomorrow: The Washington Hospital Center's First 25 Years. The hospital's history is significant in its own right because it was a struggle to provide Washington with the hospital people had been clamoring for. It was a response to the concern reflected in a 1946 Washington Post story headline which said, "District's Hospital 'Worst' in U.S., Medical Board Finds". It also seems that The Washington Hospital Center's history mirrors the history of the period which brought dramatic changes in America's approach to patient care and hospital management. Now, health care providers and managers find themselves in a new era which demands innovative strategies and financial skills that would challenge the best of the Fortune 500 scientists and executives. -

<Uke, Cdmfe^^Lmlimicmdji^

<Uke, Cdmfe^^lmlimicmdJi^ Chancellor John Stewart Bryan Twentieth President of the College 1934-1942 VOLUME X OCTOBER, 1942 8ininc=c=csESE3fca=a3£a£3£3£3fcifcS3e3rio&^ ^^^s^ri^is^s=K^s^^s^s^^s=^&^^s^^s^s^^s^s^i^s^s^^ ALUMNI ALWAYS THE WELCOME WlLLIAMSBURG * THEATRE SHOWS 3:30—7:00—9:00 DAILY WlLLIAMSBURG LODGE (SUNDAYS AT 2:00—4:00 ONLY!) CHOWNING'S TAVERN THE ENTERTAINMENT CENTER OF WlLLIAMSBURG * OPERATED BY ENJOY THE BEST IN MOTION WlLLIAMSBURG RESTORATION, INC. PICTURES. THEY ALL PLAY HERE! GREETINGS The FROM Mr. PEANUT! WlLLIAMSBURG DRUG COMPANY Welcomes the Alumni 1M Send your student sons and daughters to us for dependable pharmacy service. We will be glad to supply them with school supplies, stationery and accessories. — DELICIOUSLY FRESH — *M PLANTERS Sandwiches 1 Tobaccos / Fountain Service (SALTED) PEANUTS 8^3^»-=»=0=&3»Mra»P5M«H3^^ THE ALUMNI GAZETTE ^Jm College d(iMuam twaJiaMf inH^ima VOLUME X OCTOBER, 1942 No. 1 JOHN STEWART BRYAN RESIGNS Eight Successful Years in Review On April 11, 1942, at a meeting of the Board of Visitors, John Stewart Bryan, twentieth president of the College of William and Mary in Virginia, tendered his resignation to become effective January 1, 1943 or upon the selection of his successor. Mr. Bryan has been president of the College since the summer of 1934 when he was elected to succeed the late Dr. Julian Alvin Car- roll Chandler. He was inaugurated on October 20, 1934, in the presence of a distinguished gathering of national and state officials including the President of the United States, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and the Governor of Virginia, George Campbell Peery, both of whom received honorary degrees. -

Maryland Historical Magazine, 1986, Volume 81, Issue No. 2

Maryland Historical Masazine & o o' < GC 2 o p 3 3 re N f-' CO Published Quarterly by the Museum and Library of Maryland History The Maryland Historical Society Summer 1986 THE MARYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY OFFICERS, 1986-1987 William C. Whitridge, Chairman* Robert G. Merrick, Sr., Honorary Chairman* Brian B. Topping, President* Mrs. Charles W. Cole, Jr., Vice President* E. Phillips Hathaway, Treasurer* Mrs. Frederick W. Lafferty, Vice President* Samuel Hopkins, Asst. Secretary/Treasurer* Walter D. Pinkard, Sr., Vice President* Bryson L. Cook, Counsel* Truman T. Semans, Vice President* Leonard C. Crewe, Jr., Past President* Frank H. Weller, Jr., Vice President* J. Fife Symington, Jr.,* Richard P. Moran, Secretary* Past Chairman of the Board* The officers listed above constitute the Society's Executive Committee. BOARD OF TRUSTEES, 1986-1987 H. Furlong Baldwin Hon. Charles McC. Mathias, Jr. Mrs. Emory J. Barber, St. Mary's Co. Robert G. Merrick, Jr. Gary Black Michael Middleton, Charles Co. John E. Boulais, Caroline Co. Jack Moseley Mrs. James Frederick Colwill (Honorary) Thomas S. Nichols (Honorary) Donald L. DeVries James O. Olfson, Anne Arundel Co. Leslie B. Disharoon Mrs. David R. Owen Jerome Geckle Mrs. Brice Phillips, Worcester Co. William C. Gilchrist, Allegany Co. J. Hurst Purnell, Jr., Kent Co. Hon. Louis L. Goldstein, Calvert Co. George M. Radcliffe Kingdon Gould, Jr., Howard Co. Adrian P. Reed, Queen Anne's Co. Benjamin H. Griswold III G. Donald Riley, Carroll Co. Willard Hackerman Mrs. Timothy Rodgers R. Patrick Hayman, Somerset Co. John D. Schapiro Louis G. Hecht Jacques T. Schlenger E. Mason Hendrickson, Washington Co. Jess Joseph Smith, Jr., Prince George's Co. -

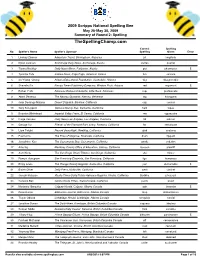

Round 2: Spelling Thespellingchamp.Com

2009 Scripps National Spelling Bee May 28-May 30, 2009 Summary of Round 2: Spelling TheSpellingChamp.com Correct Spelling No. Speller's Name Speller's Sponsor Spelling Given Error 1 Lindsey Zimmer Adventure Travel, Birmingham, Alabama jet longitude 2 Dylan Jackson Anchorage Daily News, Anchorage, Alaska sorites quarrel 3 Tianna Beckley Daily News-Miner, Fairbanks, Alaska got pharmecist E 4 Tynishia Tufu Samoa News, Pago Pago, American Samoa fun concise 5 So-Young Chung Arizona Educational Foundation, Scottsdale, Arizona wig disagreeable 6 Shevelle Six Navajo Times Publishing Company, Window Rock, Arizona red regamont E 7 Esther Park Arkansas Democrat Gazette, Little Rock, Arkansas nap promenade 8 Abeni Deveaux The Nassau Guardian, Nassau, Bahamas leg hexagonal 9 Juan Domingo Malana Desert Dispatch, Barstow, California cup census 10 Cory Klingsporn Ventura County Star, Camarillo, California ham topaz 11 Brandon Whitehead Imperial Valley Press, El Centro, California see oppressive 12 Paige Vasseur Daily News Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California lid pelican 13 George Liu Friends of the Diamond Bar Library, Pomona, California far reevaluate 14 Liam Twight Record Searchlight, Redding, California glad anatomy 15 Paul Uzzo The Press-Enterprise, Riverside, California drum flippant 16 Josephine Kao The Sacramento Bee, Sacramento, California syndic sedative 17 Amy Ng Monterey County Office of Education, Salinas, California laocoon plaintiff 18 Alex Wells The San Diego Union-Tribune, San Diego, California she mince 19 Ramya Auroprem San Francisco -

The Business Issue

VOL. 52, NO. 06 • NOVEMBER 24 - 30, 2016 Don't Miss the WI Bridge Trump Seeks Apology as ‘Hamilton’ Cast Challenges Pence - Hot Topics/Page 4 The BusinessCenter Section Issue NOVEMBER 2016 | VOL 2, ISSUE 10 Protests Continue Ahead of Trump Presidency By Stacy M. Brown cles published on Breitbart, the con- WI Senior Writer servative news website he oversaw, ABC News reported. The fallout for African Americans, President Barack Obama, the na- Muslims, Latinos and other mi- tion's first African-American presi- norities over the election of Donald dent, said Trump had "tapped into Trump as president has continued a troubling strain" in the country to with ongoing protests around the help him win the election, which has nation. led to unprecedented protests and Trump, the New York business- even a push led by some celebrities man who won more Electoral Col- to get the electorate to change its vote lege votes than Democrat Hillary when the official voting takes place on Clinton in the Nov. 8 election, has Dec. 19. managed to make matters worse by A Change.org petition, which has naming former Breitbart News chief now been signed by more than 4.3 Stephen Bannon as his chief strategist. million people, encourages members Bannon has been accused by many of the Electoral College to cast their critics of peddling or being complicit votes for Hillary Clinton when the 5 Imam Talib Shareef of Masjid Muhammad, The Nation's Mosque, stands with dozens of Christians, Jewish in white supremacy, anti-Semitism leaders and Muslims to address recent hate crimes and discrimination against Muslims during a news conference and sexism in interviews and in arti- TRUMP Page 30 before daily prayer on Friday, Nov. -

ED350369.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 350 369 UD 028 888 TITLE Introducing African American Role Models into Mathematics and Science Lesson Plans: Grades K-6. INSTITUTION American Univ., Washington, DC. Mid-Atlantic Equity Center. SPONS AGENCY Department of Education, Washington, DC. PUB DATE 92 NOTE 313p. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher)(052) Collected Works General (020) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Biographies; *Black Achievement; Black History; Black Students; *Classroom Techniques; Cultural Awareness; Curriculum Development; Elementary Education; Instructional Materials; Intermediate Grades; Lesson Plans; *Mathematics Instruction; Minority Groups; *Role Models; *Science Instruction; Student Attitudes; Teaching Guides IDENfIFIERS *African Americans ABSTRACT This guide presents lesson plans, with handouts, biographical sketches, and teaching guides, which show ways of integrating African American role models into mathematics and science lessons in kindergarten through grade 6. The guide is divided into mathematics and science sections, which each are subdivided into groupings: kindergarten through grade 2, grades 3 and 4, and grades 5 and 6. Many of the lessons can be adjusted for other grade levels. Each lesson has the following nine components:(1) concept statement; (2) instructional objectives;(3) male and female African American role models;(4) affective factors;(5) materials;(6) vocabulary; (7) teaching procedures;(8) follow-up activities; and (9) resources. The lesson plans are designed to supplement teacher-designed and textbook lessons, encourage teachers to integrate black history in their classrooms, assist students in developing an appreciation for the cultural heritage of others, elevate black students' self-esteem by presenting positive role models, and address affective factors that contribute to the achievement of blacks and other minority students in mathematics and science. -

Interpreting Racial Politics

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2013 Interpreting Racial Politics: Black and Mainstream Press Web Site Tea Party Coverage Benjamin Rex LaPoe II Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation LaPoe II, Benjamin Rex, "Interpreting Racial Politics: Black and Mainstream Press Web Site Tea Party Coverage" (2013). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 45. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/45 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. INTERPRETING RACIAL POLITICS: BLACK AND MAINSTREAM PRESS WEB SITE TEA PARTY COVERAGE A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Manship School of Mass Communication by Benjamin Rex LaPoe II B.A. West Virginia University, 2003 M.S. West Virginia University, 2008 August 2013 Table of Contents Abstract .......................................................................................................................................... iii Introduction -

RIVER ROAD MOSES CEMETERY: a Historic Preservation Evaluation

Gibson Grove Cemetery, Montgomery County THE RIVER ROAD MOSES CEMETERY: A Historic Preservation Evaluation Report prepared for the River Road African American community descendants David S. Rotenstein, PhD Silver Spring, Maryland September 2018 [email protected] (404) 326-9244 Management Summary This report presents research on the River Road Moses Cemetery site in Bethesda, Maryland. It was prepared on behalf of the River Road African American descendant community. The following sections include a historic context divided into periods developed by the Maryland Historical Trust for the evaluation of historic properties. The historic context presents substantive archival and oral history research documenting the cemetery site, the community within which it is located, the fraternal organization that founded it, and its historical connections to Washington, D.C. The historic context is used as a baseline to evaluate the property against the Montgomery County criteria for designation in the Master Plan for Historic Preservation and the National Register of Historic Places. This report finds that the River Road Moses Cemetery appears to be eligible for designation in the Montgomery County Master Plan for Historic Preservation under four criteria: for its associations with the development of Montgomery County and the region; because it exemplifies multiple aspects of Montgomery County’s heritage; because it embodies distinctive characteristics typical of its historic property type; and, because it represents a distinguishable entity within a cultural landscape. The River Road Moses Cemetery furthermore appears to be eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places under three criteria. The site appears to be eligible for listing under Criterion A for its associations with African American and suburban history; Criterion C for its architectural and landscape qualities; and, Criterion D for its potential to yield significant new information in history. -

African American Newsline Distribution Points

African American Newsline Distribution Points Deliver your targeted news efficiently and effectively through NewMediaWire’s African−American Newsline. Reach 700 leading trades and journalists dealing with political, finance, education, community, lifestyle and legal issues impacting African Americans as well as The Associated Press and Online databases and websites that feature or cover African−American news and issues. Please note, NewMediaWire includes free distribution to trade publications and newsletters. Because these are unique to each industry, they are not included in the list below. To get your complete NewMediaWire distribution, please contact your NewMediaWire account representative at 310.492.4001. A.C.C. News Weekly Newspaper African American AIDS Policy &Training Newsletter African American News &Issues Newspaper African American Observer Newspaper African American Times Weekly Newspaper AIM Community News Weekly Newspaper Albany−Southwest Georgian Newspaper Alexandria News Weekly Weekly Newspaper Amen Outreach Newsletter Newsletter Annapolis Times Newspaper Arizona Informant Weekly Newspaper Around Montgomery County Newspaper Atlanta Daily World Weekly Newspaper Atlanta Journal Constitution Newspaper Atlanta News Leader Newspaper Atlanta Voice Weekly Newspaper AUC Digest Newspaper Austin Villager Newspaper Austin Weekly News Newspaper Bakersfield News Observer Weekly Newspaper Baton Rouge Weekly Press Weekly Newspaper Bay State Banner Newspaper Belgrave News Newspaper Berkeley Tri−City Post Newspaper Berkley Tri−City Post