RIVER ROAD MOSES CEMETERY: a Historic Preservation Evaluation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black Vote Remains Crucial "I'm an Atheist and I'd Go to by D

AUGUST 2016 HEALTH WELLNESS & NUTRITION SUPPLEMENT EYE HEALTH AND IMMUNIZATION VOL. 51, NO. 44 • AUGUST 11 - 17, 2016 PRESENTED BY WI Health SupplementSPONSORS Pressure Leads to Councilman Orange’s Early Resignation - Hot Topics, Page 4 Center Section Rev. Barber First Day of Moving Forward, School Comes Before and After Early for Some DNC Convention D.C. Students By William J. Ford WI Staff Writer @jabariwill A pep-rally atmosphere greet- ed students and parents Mon- day, Aug. 8 at Turner Elementary School in southeast D.C. to begin the first day of school — a day that came a full two weeks earlier than for most of the city. Turner is one of 10 city schools taking part in the District's ex- 5Rev. William Barber II / Photo tended-school year, in which 20 by Shevry Lassiter extra days have been added for By Stacy M. Brown schools with at least 55 percent WI Senior Writer of its students not fully meeting expectations on the English and The headlines blared almost non- math portions of standardized as- stop. sessment tests in the 2014-2015 "Rev. William Barber Rattles the academic year. Windows, Shakes the DNC Walls," During that year, Turner had one of the lowest rankings among NBC News said. 5Turner Elementary School Principal Eric Bethel greets a student on Aug. 8, the first day of the extended school year for D.C. "The Rev. William Barber public schools. Turner is one of 10 schools to partake in the program to boost student achievement. / Photo by William J. Ford DCPS Page 8 dropped the mic," The Washington Post marveled. -

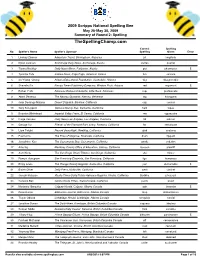

Round 2: Spelling Thespellingchamp.Com

2009 Scripps National Spelling Bee May 28-May 30, 2009 Summary of Round 2: Spelling TheSpellingChamp.com Correct Spelling No. Speller's Name Speller's Sponsor Spelling Given Error 1 Lindsey Zimmer Adventure Travel, Birmingham, Alabama jet longitude 2 Dylan Jackson Anchorage Daily News, Anchorage, Alaska sorites quarrel 3 Tianna Beckley Daily News-Miner, Fairbanks, Alaska got pharmecist E 4 Tynishia Tufu Samoa News, Pago Pago, American Samoa fun concise 5 So-Young Chung Arizona Educational Foundation, Scottsdale, Arizona wig disagreeable 6 Shevelle Six Navajo Times Publishing Company, Window Rock, Arizona red regamont E 7 Esther Park Arkansas Democrat Gazette, Little Rock, Arkansas nap promenade 8 Abeni Deveaux The Nassau Guardian, Nassau, Bahamas leg hexagonal 9 Juan Domingo Malana Desert Dispatch, Barstow, California cup census 10 Cory Klingsporn Ventura County Star, Camarillo, California ham topaz 11 Brandon Whitehead Imperial Valley Press, El Centro, California see oppressive 12 Paige Vasseur Daily News Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California lid pelican 13 George Liu Friends of the Diamond Bar Library, Pomona, California far reevaluate 14 Liam Twight Record Searchlight, Redding, California glad anatomy 15 Paul Uzzo The Press-Enterprise, Riverside, California drum flippant 16 Josephine Kao The Sacramento Bee, Sacramento, California syndic sedative 17 Amy Ng Monterey County Office of Education, Salinas, California laocoon plaintiff 18 Alex Wells The San Diego Union-Tribune, San Diego, California she mince 19 Ramya Auroprem San Francisco -

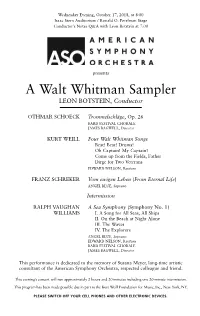

A Walt Whitman Sampler LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor

Wednesday Evening, October 17, 2018, at 8:00 Isaac Stern Auditorium / Ronald O. Perelman Stage Conductor’s Notes Q&A with Leon Botstein at 7:00 presents A Walt Whitman Sampler LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor OTHMAR SCHOECK Trommelschläge, Op. 26 BARD FESTIVAL CHORALE JAMES BAGWELL, Director KURT WEILL Four Walt Whitman Songs Beat! Beat! Drums! Oh Captain! My Captain! Come up from the Fields, Father Dirge for Two Veterans EDWARD NELSON, Baritone FRANZ SCHREKER Vom ewigen Leben (From Eternal Life) ANGEL BLUE, Soprano Intermission RALPH VAUGHAN A Sea Symphony (Symphony No. 1) WILLIAMS I. A Song for All Seas, All Ships II. On the Beach at Night Alone III. The Waves IV. The Explorers ANGEL BLUE, Soprano EDWARD NELSON, Baritone BARD FESTIVAL CHORALE JAMES BAGWELL, Director This performance is dedicated to the memory of Susana Meyer, long-time artistic consultant of the American Symphony Orchestra, respected colleague and friend. This evening’s concert will run approximately 2 hours and 20 minutes including one 20-minute intermission. This program has been made possible due in part to the Kurt Weill Foundation for Music, Inc., New York, NY. PLEASE SWITCH OFF YOUR CELL PHONES AND OTHER ELECTRONIC DEVICES. FROM THE Music Director Whitman and Democracy comprehend the English of Shakespeare by Leon Botstein or even Jane Austen without some reflection. (Indeed, even the space Among the most arguably difficult of between one generation and the next literary enterprises is the art of transla- can be daunting.) But this is because tion. Vladimir Nabokov was obsessed language is a living thing. There is a about the matter; his complicated and decided family resemblance over time controversial views on the processes of within a language, but the differences transferring the sensibilities evoked by in usage and meaning and in rhetoric one language to another have them- and significance are always developing. -

The Business Issue

VOL. 52, NO. 06 • NOVEMBER 24 - 30, 2016 Don't Miss the WI Bridge Trump Seeks Apology as ‘Hamilton’ Cast Challenges Pence - Hot Topics/Page 4 The BusinessCenter Section Issue NOVEMBER 2016 | VOL 2, ISSUE 10 Protests Continue Ahead of Trump Presidency By Stacy M. Brown cles published on Breitbart, the con- WI Senior Writer servative news website he oversaw, ABC News reported. The fallout for African Americans, President Barack Obama, the na- Muslims, Latinos and other mi- tion's first African-American presi- norities over the election of Donald dent, said Trump had "tapped into Trump as president has continued a troubling strain" in the country to with ongoing protests around the help him win the election, which has nation. led to unprecedented protests and Trump, the New York business- even a push led by some celebrities man who won more Electoral Col- to get the electorate to change its vote lege votes than Democrat Hillary when the official voting takes place on Clinton in the Nov. 8 election, has Dec. 19. managed to make matters worse by A Change.org petition, which has naming former Breitbart News chief now been signed by more than 4.3 Stephen Bannon as his chief strategist. million people, encourages members Bannon has been accused by many of the Electoral College to cast their critics of peddling or being complicit votes for Hillary Clinton when the 5 Imam Talib Shareef of Masjid Muhammad, The Nation's Mosque, stands with dozens of Christians, Jewish in white supremacy, anti-Semitism leaders and Muslims to address recent hate crimes and discrimination against Muslims during a news conference and sexism in interviews and in arti- TRUMP Page 30 before daily prayer on Friday, Nov. -

ED350369.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 350 369 UD 028 888 TITLE Introducing African American Role Models into Mathematics and Science Lesson Plans: Grades K-6. INSTITUTION American Univ., Washington, DC. Mid-Atlantic Equity Center. SPONS AGENCY Department of Education, Washington, DC. PUB DATE 92 NOTE 313p. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher)(052) Collected Works General (020) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Biographies; *Black Achievement; Black History; Black Students; *Classroom Techniques; Cultural Awareness; Curriculum Development; Elementary Education; Instructional Materials; Intermediate Grades; Lesson Plans; *Mathematics Instruction; Minority Groups; *Role Models; *Science Instruction; Student Attitudes; Teaching Guides IDENfIFIERS *African Americans ABSTRACT This guide presents lesson plans, with handouts, biographical sketches, and teaching guides, which show ways of integrating African American role models into mathematics and science lessons in kindergarten through grade 6. The guide is divided into mathematics and science sections, which each are subdivided into groupings: kindergarten through grade 2, grades 3 and 4, and grades 5 and 6. Many of the lessons can be adjusted for other grade levels. Each lesson has the following nine components:(1) concept statement; (2) instructional objectives;(3) male and female African American role models;(4) affective factors;(5) materials;(6) vocabulary; (7) teaching procedures;(8) follow-up activities; and (9) resources. The lesson plans are designed to supplement teacher-designed and textbook lessons, encourage teachers to integrate black history in their classrooms, assist students in developing an appreciation for the cultural heritage of others, elevate black students' self-esteem by presenting positive role models, and address affective factors that contribute to the achievement of blacks and other minority students in mathematics and science. -

Interpreting Racial Politics

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2013 Interpreting Racial Politics: Black and Mainstream Press Web Site Tea Party Coverage Benjamin Rex LaPoe II Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation LaPoe II, Benjamin Rex, "Interpreting Racial Politics: Black and Mainstream Press Web Site Tea Party Coverage" (2013). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 45. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/45 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. INTERPRETING RACIAL POLITICS: BLACK AND MAINSTREAM PRESS WEB SITE TEA PARTY COVERAGE A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Manship School of Mass Communication by Benjamin Rex LaPoe II B.A. West Virginia University, 2003 M.S. West Virginia University, 2008 August 2013 Table of Contents Abstract .......................................................................................................................................... iii Introduction -

Amalie Joachim's 1892 American Tour

Volume XXXV, Number 1 Spring 2017 Amalie Joachim’s 1892 American Tour By the 1890s, American audiences had grown accustomed to the tours of major European artists, and the successes of Jenny Lind and Anton Rubinstein created high expectations for the performers who came after them. Amalie Joachim toured from March to May of 1892, during the same months as Paderewski, Edward Lloyd, and George and Lillian Henschel.1 Although scholars have explored the tours of artists such as Hans von Bülow and Rubinstein, Joachim’s tour has gone largely unnoticed. Beatrix Borchard, Joachim’s biographer, has used privately held family letters to chronicle some of Joachim’s own responses to the tour, as well as a sampling of the reviews of the performer’s New York appearances. She does not provide complete details of Joachim’s itinerary, however, or performances outside of New York. Although Borchard notes that Villa Whitney White traveled with Joachim and that the two performed duets, she did not realize that White was an American student of Joachim who significantly influenced the tour.2 The women’s activities, however, can be traced through reviews and advertisements in newspapers and music journals, as well as brief descriptions in college yearbooks. These sources include the places Joachim performed, her repertoire, and descriptions of the condition of her voice and health. Most of Joachim’s performances were in and around Boston. During some of her time in this city, she stayed with her Amalie Joachim, portrait given to Clara Kathleen Rogers. friend, the former opera singer Clara Kathleen Rogers. -

News and Events

Volume 15 Number 1 topical Weill Spring 1997 A supplement to the Kurt Weill Newsletter news &news events The Royal National Theatre Ushers in Lady in the Dark &news events Opening Catherine Ashmore (right). Catherine Ashmore Scenes (left), Damm Photos: Van Then and Now . Gertrude Lawrence as Liza in 1941 Maria Friedman as Liza in 1997 (with Richard Hale). (with Hugh Ross). The production by Francesca Zambello is stylish, The show is original and appealing and, as heroines go, so is Maria Friedman. Her Liza Elliott stalks into her restrained, cerebral. Weill’s music is plangent and shrink’s eyrie radiating nervy, brittle assurance, then sinuous, a remarkable synthesis of Weimar jazz and spins rapturously off into the first of the dream- pre-Sondheim querulousness. Maria Friedman, sure- sequences that interrupt the more realistic proceed- ly confirmed now as our supreme musical actress, ings. Our own Tina Brown would have to be promot- negotiates her backward spiral with exuberant grace ed from the chair of the New Yorker to the throne of and wit, swirling in mists and ballgowns, defiantly zip- England to match a fantasy like that. ping on the Schiaparelli frock when she takes off with — Benedict Nightingale, “Freudian drama that does not a movie star hunk (the Victor Mature role is occupied shrink from emotion,” The Times (12 March 1997) by a suitably anaemic grinner, Steven Edward Moore) and even stepping daintily across a tightrope, in Adrianne Lobel has designed a conceptual setting of sail-like Stoppardian vein, to prove she is a “proponent of triangles which introduces a number of staging constraints. -

African American Newsline Distribution Points

African American Newsline Distribution Points Deliver your targeted news efficiently and effectively through NewMediaWire’s African−American Newsline. Reach 700 leading trades and journalists dealing with political, finance, education, community, lifestyle and legal issues impacting African Americans as well as The Associated Press and Online databases and websites that feature or cover African−American news and issues. Please note, NewMediaWire includes free distribution to trade publications and newsletters. Because these are unique to each industry, they are not included in the list below. To get your complete NewMediaWire distribution, please contact your NewMediaWire account representative at 310.492.4001. A.C.C. News Weekly Newspaper African American AIDS Policy &Training Newsletter African American News &Issues Newspaper African American Observer Newspaper African American Times Weekly Newspaper AIM Community News Weekly Newspaper Albany−Southwest Georgian Newspaper Alexandria News Weekly Weekly Newspaper Amen Outreach Newsletter Newsletter Annapolis Times Newspaper Arizona Informant Weekly Newspaper Around Montgomery County Newspaper Atlanta Daily World Weekly Newspaper Atlanta Journal Constitution Newspaper Atlanta News Leader Newspaper Atlanta Voice Weekly Newspaper AUC Digest Newspaper Austin Villager Newspaper Austin Weekly News Newspaper Bakersfield News Observer Weekly Newspaper Baton Rouge Weekly Press Weekly Newspaper Bay State Banner Newspaper Belgrave News Newspaper Berkeley Tri−City Post Newspaper Berkley Tri−City Post -

The Presideut's Column

KURT WEILL NEWSLETTER PUBLISHED BY THE KURT WEILL FOUNDATION FOR MUSIC HENRY MARX, EDITOR FALL 1983 lishers and vendors throughout the world. performances, recordings, productions, he Presideut's My own research and performing ac workshops, fellowships, and scholar Column: tivities had to be suspended while I ships. Already the Foundation staff of doggedly learned about international Mrs. Symonette and Mr. Farneth, with the A PROFILE OF copyright laws, terminations, extensions, aid of a half-time secretary, are answering T the differences between small, grand inquiries and assisting scholars, perform THE FOUNDATION and print rights, performing rights so ers, conductors, and producers with vari It's hard for me to believe that Lenya has cieties, and the curious internal mecha ous projects. Now that the Foundation's been gone nearly two years. When she nisms of the "publishing" industry existence is secure and its role defined, asked me to succeed her as President of wherein few "publishers" actually print we are entering an exciting new phase of the Foundation, I had no inkling that music anymore. My naivete was neces activities. This is the first issue of a sem, these two years would be the most hec sarily short-lived as I reviewed contracts annual newsletter; 1984 will witness the tic. frustrating, rewarding and exhilarating and accounts that apparently had never publication of Volume I of a Weill Year of my life. Although it had been chartered been verified, much less audited. I would book; long-term plans are being formu nearly twenty years ago and had been hope that soon it will no longer be impos lated for publication, performance, or active sporadically during those two de sible to purchase or rent certain scores in recording of such "lost'' works as Der cades, the Foundation had been little this country because the U.S. -

Events Around Town for the Festival!

“The jealous are troublesome to others, but a torment to themselves.” – William Penn Edelman Examines Hidden Leaders of Social Change See Page 27 • Celebrating 49 Years of Service • Serving More Than 50,000 African American Readers Throughout The Metropolitan Area / Vol. 49, No.24 Mar. 27 - Apr. 2, 2014 Events Around Town for the Festival! District residents and tourists alike, are looking forward to the upcoming National Cherry Blossom Festival Parade which will take place on Saturday, April 12 along Constitution Avenue in Northwest. Meanwhile, a number of events throughout the festival will provide an opportunity to enjoy various cuisines, music and art. See Story on Page 28. /Photo by Ron Engle for the National Cherry Blossom Festival Deadline Nears for Health Care Enrollment for insurance under President as many individuals as possible Benefit Exchange Authority in The president and officials in Signup Drive Barack Obama’s signature health before the Monday, March 31, Northwest. his administration said they’re Locations Include care law, recruiters in the District cut off date. “The young people, the seeking as many as seven million Laundromats, Lounges are leaving no stone unturned. “Our philosophy is to take it young invincibles, we are taking individuals to sign up for insur- Workers and volunteers are to the streets, take it to places of it to them at the nightclubs, at ance under the Affordable Care By Stacy M. Brown targeting young people, partic- work, where people eat, drink, the sports bars and where they Act, or ACA. WI Contributing Writer ularly those between the ages and pray,” said Dr. -

Passioned, Radical Leader Who Incorporating Their Own

Vol. 59 No. 11 March 13 - 19, 2019 CELEBRATING MARCH 14, 2018 25 Portland and Seattle Volume XL No. 24 CENTS BLACK MEN ARRESTED AT STARBUCKS WANT CHANGE IN U.S. RACIAL ATTITUDES - PG. 2 News ..............................3,8-10 A & E .....................................6-7 Opinion ...................................2 NRA Gives to Schools ......8 NATIONAL NEWSPAPER PUBLISHERS ASSOCIATION CHALLENGING PEOPLE TO SHAPE A BETTER FUTURE NOW Calendars ...........................4-5 Bids/Classifieds ....................11 THE SKANNER NEWS READERS POLL Should Portland Public Schools change the name of Jefferson High School? (451 responses) YES THE NATION’S ONLY BLACK DAILY 129 (29%) NO Reporting and Recording Black History 322 (71%) STUDENTS WALK OUT 75 Cents VOL. 47 NO. 28 FRIDAY, APRIL 20, 2018 Final Seventy-one percent of respondents to a The Skanner News poll favored keeping the name of Thomas Jefferson High School intact. CENTER192 FOCUSES ON YOUTH POLL RESULTS: YEARS OF THE 71 Percent of TO HELP SAVE THE PLANET The Skanner’s Readers Oppose BLACK PRESS Jefferson Name Change Alumni association circulating a petition OF AMERICA opposed to name change PHOTO BY SUSAN FRIED SUSAN BY PHOTO By Christen McCurdy Hundreds of students from Washington Middle School and Garfield High School joined students across the country in a walkout and 17 minutes of silence Of The Skanner News to show support for the lives lost at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Florida Feb. 14 and to let elected officials know that they want stricter gun control laws. he results of a poll by The Skanner News, which opened Feb. 22 and closed Tuesday, favor keeping the Oregon Introduces ‘Gun Violence Restraining Orders’ Tname of North Portland’s Thomas Jefferson High School.