Amalie Joachim's 1892 American Tour

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edward Channing's Writing Revolution: Composition Prehistory at Harvard

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Spring 2017 EDWARD CHANNING’S WRITING REVOLUTION: COMPOSITION PREHISTORY AT HARVARD, 1819-1851 Bradfield dwarE d Dittrich University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Dittrich, Bradfield dwarE d, "EDWARD CHANNING’S WRITING REVOLUTION: COMPOSITION PREHISTORY AT HARVARD, 1819-1851" (2017). Doctoral Dissertations. 163. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/163 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EDWARD CHANNING’S WRITING REVOLUTION: COMPOSITION PREHISTORY AT HARVARD, 1819-1851 BY BRADFIELD E. DITTRICH B.A. St. Mary’s College of Maryland, 2003 M.A. Salisbury University, 2009 DISSERTATION Submitted to the University of New Hampshire in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English May 2017 ii ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ©2017 Bradfield E. Dittrich iii EDWARD CHANNING’S WRITING REVOLUTION: COMPOSITION PREHISTORY AT HARVARD, 1819-1851 BY BRADFIELD E. DITTRICH This dissertation has been has been examined and approved by: Dissertation Chair, Christina Ortmeier-Hooper, Associate Professor of English Thomas Newkirk, Professor Emeritus of English Cristy Beemer, Associate Professor of English Marcos DelHierro, Assistant Professor of English Alecia Magnifico, Assistant Professor of English On April 7, 2017 Original approval signatures are on file with the University of New Hampshire Graduate School. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season

// BOSTON T /?, SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA THURSDAY B SERIES EIGHTY-SEVENTH SEASON 1967-1968 wgm _«9M wsBt Exquisite Sound From the palace of ancient Egyp to the concert hal of our moder cities, the wondroi music of the harp hi compelled attentio from all peoples and a countries. Through th passage of time man changes have been mac in the original design. Tl early instruments shown i drawings on the tomb < Rameses II (1292-1225 B.C were richly decorated bv lacked the fore-pillar. Lato the "Kinner" developed by tl Hebrews took the form as m know it today. The pedal hai was invented about 1720 by Bavarian named Hochbrucker an through this ingenious device it b came possible to play in eight maj< and five minor scales complete. Tods the harp is an important and familij instrument providing the "Exquisi* Sound" and special effects so importai to modern orchestration and arrang ment. The certainty of change mak< necessary a continuous review of yoi insurance protection. We welcome tl opportunity of providing this service f< your business or personal needs. We respectfully invite your inquiry CHARLES H. WATKINS & CO. Richard P. Nyquist — Charles G. Carleton 147 Milk Street Boston, Massachusetts Telephone 542-1250 OBRION, RUSSELL & CO. Insurance of Every Description EIGHTY-SEVENTH SEASON 1967-1968 BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ERICH LEINSDORF Music Director CHARLES WILSON Assistant Conductor THE TRUSTEES OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA INC. HENRY B. CABOT President TALCOTT M. BANKS Vice-President JOHN L. THORNDIKE Treasurer PHILIP K. ALLEN E. MORTON JENNINGS JR ABRAM BERKOWITZ EDWARD M. KENNEDY THEODORE P. -

Seeking a Forgotten History

HARVARD AND SLAVERY Seeking a Forgotten History by Sven Beckert, Katherine Stevens and the students of the Harvard and Slavery Research Seminar HARVARD AND SLAVERY Seeking a Forgotten History by Sven Beckert, Katherine Stevens and the students of the Harvard and Slavery Research Seminar About the Authors Sven Beckert is Laird Bell Professor of history Katherine Stevens is a graduate student in at Harvard University and author of the forth- the History of American Civilization Program coming The Empire of Cotton: A Global History. at Harvard studying the history of the spread of slavery and changes to the environment in the antebellum U.S. South. © 2011 Sven Beckert and Katherine Stevens Cover Image: “Memorial Hall” PHOTOGRAPH BY KARTHIK DONDETI, GRADUATE SCHOOL OF DESIGN, HARVARD UNIVERSITY 2 Harvard & Slavery introducTION n the fall of 2007, four Harvard undergradu- surprising: Harvard presidents who brought slaves ate students came together in a seminar room to live with them on campus, significant endow- Ito solve a local but nonetheless significant ments drawn from the exploitation of slave labor, historical mystery: to research the historical con- Harvard’s administration and most of its faculty nections between Harvard University and slavery. favoring the suppression of public debates on Inspired by Ruth Simmon’s path-breaking work slavery. A quest that began with fears of finding at Brown University, the seminar’s goal was nothing ended with a new question —how was it to gain a better understanding of the history of that the university had failed for so long to engage the institution in which we were learning and with this elephantine aspect of its history? teaching, and to bring closer to home one of the The following pages will summarize some of greatest issues of American history: slavery. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 27,1907-1908, Trip

CARNEGIE HALL - - NEW YORK Twenty-second Season in New York DR. KARL MUCK, Conductor fnigrammra of % FIRST CONCERT THURSDAY EVENING, NOVEMBER 7 AT 8.15 PRECISELY AND THK FIRST MATINEE SATURDAY AFTERNOON, NOVEMBER 9 AT 2.30 PRECISELY WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIP- TIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE PUBLISHED BY C. A. ELLIS, MANAGER : Piano. Used and indorsed by Reisenauer, Neitzel, Burmeister, Gabrilowitsch, Nordica, Campanari, Bispham, and many other noted artists, will be used by TERESA CARRENO during her tour of the United States this season. The Everett piano has been played recently under the baton of the following famous conductors Theodore Thomas Franz Kneisel Dr. Karl Muck Fritz Scheel Walter Damrosch Frank Damrosch Frederick Stock F. Van Der Stucken Wassily Safonoff Emil Oberhoffer Wilhelm Gericke Emil Paur Felix Weingartner REPRESENTED BY THE JOHN CHURCH COMPANY . 37 West 32d Street, New York Boston Symphony Orchestra PERSONNEL TWENTY-SEVENTH SEASON, 1907-1908 Dr. KARL MUCK, Conductor First Violins. Wendling, Carl, Roth, O. Hoffmann, J. Krafft, W. Concert-master. Kuntz, D. Fiedler, E. Theodorowicz, J. Czerwonky, R. Mahn, F. Eichheim, H. Bak, A. Mullaly, J. Strube, G. Rissland, K. Ribarsch, A. Traupe, W. < Second Violins. • Barleben, K. Akeroyd, J. Fiedler, B. Berger, H. Fiumara, P. Currier, F. Rennert, B. Eichler, J. Tischer-Zeitz, H Kuntz, A. Swornsbourne, W. Goldstein, S. Kurth, R. Goldstein, H. Violas. Ferir, E. Heindl, H. Zahn, F. Kolster, A. Krauss, H. Scheurer, K. Hoyer, H. Kluge, M. Sauer, G. Gietzen, A. t Violoncellos. Warnke, H. Nagel, R. Barth, C. Loefner, E. Heberlein, H. Keller, J. Kautzenbach, A. Nast, L. -

Brahms Symphony 2 Gardiner

Brahms Symphony 2 Gardiner 1 Johannes Brahms 1833-1897 1 Alto Rhapsody Op.53 (1869) 12:57 Franz Schubert 1797-1828 2 Gesang der Geister über den Wassern D714 (1821) 12:18 3 Gruppe aus dem Tartarus D583 (1817, arr. Brahms 1871) 2:20 4 An Schwager Kronos D369 (1816, arr. Brahms 1871) 2:28 Symphony No.2 in D major Op.73 (1877) 5 I Allegro non troppo 19:42 6 II Adagio non troppo – L’istesso tempo, ma grazioso 9:28 7 III Allegretto grazioso (quasi andantino) – Presto ma non assai – Tempo I 5:06 8 IV Allegro con spirito 9:05 73:59 Nathalie Stutzmann contralto Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique The Monteverdi Choir John Eliot Gardiner Recorded live at the Salle Pleyel, Paris, November 2007 2 Brahms: Roots and memory John Eliot Gardiner To me Brahms’ large-scale music is brimful of vigour, drama and a driving passion. ‘Fuego y cristal’ was how Jorge Luis Borges once described it. How best to release all that fire and crystal, then? One way is to set his symphonies in the context of his own superb and often neglected choral music, and that of the old masters he particularly cherished (Schütz and Bach especially) and of recent heroes of his (Mendelssohn, Schubert and Schumann). This way we are able to gain a new perspective on his symphonic compositions, drawing attention to the intrinsic vocality at the heart of his writing for orchestra. Composing such substantial choral works as the Schicksalslied, the Alto Rhapsody, Nänie and the German Requiem gave Brahms invaluable experience of orchestral writing years before he brought his first symphony to fruition: they were the vessels for some of his most profound thoughts, revealing at times an almost desperate urge to communicate things of import. -

History and Bibliography of American Newspapers 1690-1820

Additions and Corrections to History and Bibliography of American Newspapers 1690-1820 BY CLARENCE S. BRIGHAM FOREWORD HESE additions and corrections cover only certain T fields of the parent work which was published in 1947 in two volumes. All new titles are carefully entered and described, although only nine such titles have been dis- covered in the last thirteen years. Only unique issues acquired by libraries have been entered. Certain libraries, like the Library of Congress, the New York libraries, and especially the American Antiquarian Society, have acquired thousands of issues in the past few years, but these are all in long or complete files and generally are not mentioned. Libraries which have sent me lists of issues recently obtained should note this fact and not expect to find all copies listed. In a few cases long files acquired by libraries have been entered, on the assumption that they might contain a few issues not in the supposedly complete files in other libraries. New biographical facts concerning publishers, printers, and editors are entered. Frequently, the complete spellings of Christian names hitherto known only by initials are given. Important changes in the historical accounts of newspapers i6 AMERICAN ANTIQUARIAN SOCIETY [April, have been entered. Most of these changes have been ob- tained through correspondence, or by noting the record of additions in printed reports or bulletins of libraries. There has been no attempt to visit the many libraries to re-examine the various files. Microfilm reproductions issued by various libraries in the past few years have been noted, although not the many libraries purchasing such microfilm files. -

City Research Online

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pace, I. (2012). Instrumental performance in the nineteenth century. In: Lawson, C. and Stowell, R. (Eds.), The Cambridge History of Musical Performance. (pp. 643-695). Cambridge University Press. This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/6305/ Link to published version: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CHOL9780521896115.027 Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] C:/ITOOLS/WMS/CUP-NEW/2654833/WORKINGFOLDER/LASL/9780521896115C26.3D 643 [643–695] 5.9.2011 7:13PM . 26 . Instrumental performance in the nineteenth century IAN PACE 1815–1848 Beethoven, Schubert and musical performance in Vienna from the Congress until 1830 As a major centre with a long tradition of performance, Vienna richly reflects -

From Page to Stage: Wagner As Regisseur

Wagner Ia 5/27/09 3:55 PM Page 3 Copyrighted Material From Page to Stage: Wagner as Regisseur KATHERINE SYER Nowadays we tend to think of Richard Wagner as an opera composer whose ambitions and versatility extended beyond those of most musicians. From the beginning of his career he assumed the role of his own librettist, and he gradually expanded his sphere of involvement to include virtually all aspects of bringing an opera to the stage. If we focus our attention on the detailed dramatic scenarios he created as the bases for his stage works, we might well consider Wagner as a librettist whose ambitions extended rather unusually to the area of composition. In this light, Wagner could be considered alongside other theater poets who paid close attention to pro- duction matters, and often musical issues as well.1 The work of one such figure, Eugène Scribe, formed the foundation of grand opera as it flour- ished in Paris in the second quarter of the nineteenth century. Wagner arrived in this operatic epicenter in the fall of 1839 with work on his grand opera Rienzi already under way, but his prospects at the Opéra soon waned. The following spring, Wagner sent Scribe a dramatic scenario for a shorter work hoping that the efforts of this famous librettist would help pave his way to success. Scribe did not oblige. Wagner eventually sold the scenario to the Opéra, but not before transforming it into a markedly imaginative libretto for his own use.2 Wagner’s experience of operatic stage produc- tion in Paris is reflected in many aspects of the libretto of Der fliegende Holländer, the beginning of an artistic vision that would draw him increas- ingly deeper into the world of stage direction and production. -

Le Corsaire Overture, Op. 21

Any time Joshua Bell makes an appearance, it’s guaranteed to be impressive! I can’t wait to hear him perform the monumental Brahms Violin Concerto alongside some fireworks for the orchestra. It’s a don’t-miss evening! EMILY GLOVER, NCS VIOLIN Le Corsaire Overture, Op. 21 HECTOR BERLIOZ BORN December 11, 1803, in Côte-Saint-André, France; died March 8, 1869, in Paris PREMIERE Composed 1844, revised before 1852; first performance January 19, 1845, in Paris, conducted by the composer OVERVIEW The Random House Dictionary defines “corsair” both as “a pirate” and as “a ship used for piracy.” Berlioz encountered one of the former on a wild, stormy sea voyage in 1831 from Marseilles to Livorno, on his way to install himself in Rome as winner of the Prix de Rome. The grizzled old buccaneer claimed to be a Venetian seaman who had piloted the ship of Lord Byron during the poet’s adventures in the Adriatic and the Greek archipelago, and his fantastic tales helped the young composer keep his mind off the danger aboard the tossing vessel. They landed safely, but the experience of that storm and the image of Lord Byron painted by the corsair stayed with him. When Berlioz arrived in Rome, he immersed himself in Byron’s poem The Corsair, reading much of it in, of all places, St. Peter’s Basilica. “During the fierce summer heat I spent whole days there ... drinking in that burning poetry,” he wrote in his Memoirs. It was also at that time that word reached him that his fiancée in Paris, Camile Moke, had thrown him over in favor of another suitor. -

Florida State University Libraries

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2009 Gustav Mahler, Alfred Roller, and the Wagnerian Gesamtkunstwerk: Tristan and Affinities Between the Arts at the Vienna Court Opera Stephen Carlton Thursby Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC GUSTAV MAHLER, ALFRED ROLLER, AND THE WAGNERIAN GESAMTKUNSTWERK: TRISTAN AND AFFINITIES BETWEEN THE ARTS AT THE VIENNA COURT OPERA By STEPHEN CARLTON THURSBY A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2009 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Stephen Carlton Thursby defended on April 3, 2009. _______________________________ Denise Von Glahn Professor Directing Dissertation _______________________________ Lauren Weingarden Outside Committee Member _______________________________ Douglass Seaton Committee Member Approved: ___________________________________ Douglass Seaton, Chair, Musicology ___________________________________ Don Gibson, Dean, College of Music The Graduate School has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii To my wonderful wife Joanna, for whose patience and love I am eternally grateful. In memory of my grandfather, James C. Thursby (1926-2008). iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The completion of this dissertation would not have been possible without the generous assistance and support of numerous people. My thanks go to the staff of the Austrian Theater Museum and Austrian National Library-Music Division, especially to Dr. Vana Greisenegger, curator of the visual materials in the Alfred Roller Archive of the Austrian Theater Museum. I would also like to thank the musicology faculty of the Florida State University College of Music for awarding me the Curtis Mayes Scholar Award, which funded my dissertation research in Vienna over two consecutive summers (2007- 2008). -

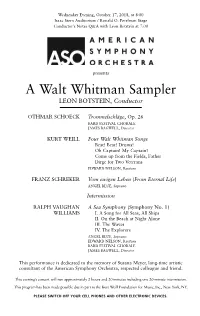

A Walt Whitman Sampler LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor

Wednesday Evening, October 17, 2018, at 8:00 Isaac Stern Auditorium / Ronald O. Perelman Stage Conductor’s Notes Q&A with Leon Botstein at 7:00 presents A Walt Whitman Sampler LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor OTHMAR SCHOECK Trommelschläge, Op. 26 BARD FESTIVAL CHORALE JAMES BAGWELL, Director KURT WEILL Four Walt Whitman Songs Beat! Beat! Drums! Oh Captain! My Captain! Come up from the Fields, Father Dirge for Two Veterans EDWARD NELSON, Baritone FRANZ SCHREKER Vom ewigen Leben (From Eternal Life) ANGEL BLUE, Soprano Intermission RALPH VAUGHAN A Sea Symphony (Symphony No. 1) WILLIAMS I. A Song for All Seas, All Ships II. On the Beach at Night Alone III. The Waves IV. The Explorers ANGEL BLUE, Soprano EDWARD NELSON, Baritone BARD FESTIVAL CHORALE JAMES BAGWELL, Director This performance is dedicated to the memory of Susana Meyer, long-time artistic consultant of the American Symphony Orchestra, respected colleague and friend. This evening’s concert will run approximately 2 hours and 20 minutes including one 20-minute intermission. This program has been made possible due in part to the Kurt Weill Foundation for Music, Inc., New York, NY. PLEASE SWITCH OFF YOUR CELL PHONES AND OTHER ELECTRONIC DEVICES. FROM THE Music Director Whitman and Democracy comprehend the English of Shakespeare by Leon Botstein or even Jane Austen without some reflection. (Indeed, even the space Among the most arguably difficult of between one generation and the next literary enterprises is the art of transla- can be daunting.) But this is because tion. Vladimir Nabokov was obsessed language is a living thing. There is a about the matter; his complicated and decided family resemblance over time controversial views on the processes of within a language, but the differences transferring the sensibilities evoked by in usage and meaning and in rhetoric one language to another have them- and significance are always developing. -

Toronto Public Library

Toronto Public Library THIRTY-FIRST ANNUAL REPORT 1914 OONTENTS. Chairmen of the Board of :Management II List of Members and officers of the Board of Management ......... , 8 List of Libraries and Hours of Service . • . • . • . • . • • . • Report of Chairman of the Board ............ , ••.•.........•.••. , • 15 Report of Chief Librarian ...••• , •••...••...•..•••••••.••.•.••.. , • 8 Reports from Departments:- The Reference Department . • . • . 11 The Cataloguing Department ....................... , . • . 12 The Chlldren 's Department . 13 The Municipal Reference Department . 14 The Accessioning Department . 15 The Registration Department ............. , . 15 The· Stock Department . • . • • . 15 The Book-binding Department .......... , . • . HI Toronto Public Library Club ...... , ........ , , ................... , . 17 Approximate Distribution of Books by Classes and by Libraries . 19 Circulation of Books during 1914 . • . 20 Form for Library Statistics ..........................• , . • • . 21 Financial Statement! ...........................•••.• , , , •.• •..•..... 24. 25 List of Periodicals ........................... , ..... ~ ................ 26-86 THOMAS W . BANTON Chairman of Libra ry Board , t 9 t 4 . TORONTO PUBLIC LIBRARY THIRTY-FIRST ANNUAL REPORT FOR THE YEAR 1914 The Armac Preas, limited iforonto. Chairmen of the Board of Management .John Hallam 1883 John Hallam JS.~4 John Taylor ..................................... 1885 George Wright, M.A., M.B. ....................... l~S6 Lt.-Col. James :Mason ...........................