African American Employment, Population & Housing Trends In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ULI Washington 2018 Trends Conference Sponsors

ULI Washington 2018 Trends Conference Sponsors PRINCIPAL EVENT SPONSOR MAJOR EVENT SPONSORS EVENT SPONSORS ARCHITECTURE LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE INTERIOR DESIGN PLANNING April 17, 2018 Greetings from the Trends Committee Co-Chairs Welcome to the 21st Annual ULI Washington Trends Conference. We are very excited you are here, CONTINUING and hope you enjoy the program. Our committees came up with a diverse set of sessions, focusing EDUCATION CREDITS on ideas and trends that people in the industry are talking about today. The theme of the day The Trends Conference has is Transformational Change: Communities at the Crossroads. Speaking of trends, we are happy been approved for 6.5 hours to report that almost half of our speakers and presenters are women this year, bringing diverse of continuing education perspectives to the program. credits by the American Institute of Architects (AIA). We couldn’t have a trends conference without discussing current economic trends, so we will start The Trends Conference is also the day with a presentation by Kevin Thorpe, Global Chief Economist from Cushman & Wakefield approved for 6.5 credits by the entitled Economic & Commercial Real Estate Outlook: Growth, Anxiety and DC CRE. American Institute of Certified Planners (AICP). Forms to To give you a brief summary of the day, we’ll start with concurrent sessions on parking and record conference attendance reinventing suburbs. After that, we will have sessions on affordable housing and live performance. will be available at 3 pm at the After lunch, we will have three “quick hits” features focusing on food and blockchain impacts on conference registration area. -

Black Vote Remains Crucial "I'm an Atheist and I'd Go to by D

AUGUST 2016 HEALTH WELLNESS & NUTRITION SUPPLEMENT EYE HEALTH AND IMMUNIZATION VOL. 51, NO. 44 • AUGUST 11 - 17, 2016 PRESENTED BY WI Health SupplementSPONSORS Pressure Leads to Councilman Orange’s Early Resignation - Hot Topics, Page 4 Center Section Rev. Barber First Day of Moving Forward, School Comes Before and After Early for Some DNC Convention D.C. Students By William J. Ford WI Staff Writer @jabariwill A pep-rally atmosphere greet- ed students and parents Mon- day, Aug. 8 at Turner Elementary School in southeast D.C. to begin the first day of school — a day that came a full two weeks earlier than for most of the city. Turner is one of 10 city schools taking part in the District's ex- 5Rev. William Barber II / Photo tended-school year, in which 20 by Shevry Lassiter extra days have been added for By Stacy M. Brown schools with at least 55 percent WI Senior Writer of its students not fully meeting expectations on the English and The headlines blared almost non- math portions of standardized as- stop. sessment tests in the 2014-2015 "Rev. William Barber Rattles the academic year. Windows, Shakes the DNC Walls," During that year, Turner had one of the lowest rankings among NBC News said. 5Turner Elementary School Principal Eric Bethel greets a student on Aug. 8, the first day of the extended school year for D.C. "The Rev. William Barber public schools. Turner is one of 10 schools to partake in the program to boost student achievement. / Photo by William J. Ford DCPS Page 8 dropped the mic," The Washington Post marveled. -

Equity. Resilience. Innovation

FEDERAL CITY COUNCIL CATALYSTfederalcitycouncil.org | December 2020 Equity. Resilience. Innovation. Catalyst Special Edition District Strong Economic Recovery Mini-Conference Summary Report Table of Contents Letter from the CEO and Executive Director 1 Health Foundations of the Recovery 2 Foundations for Recovery and Return to Work 4 Executive and Legislative Leadership Perspectives 6 District Strong: Outlook 8 Mini-Conference Co-Hosts Sponsors Research Partners Business Community Partners Letter from the CEO and Executive Director Dear Friends, At the Federal City Council (FC2), we tend to look forward, conducted over a six-week knowing that the path to creating a more dynamic future for period in September and the District of Columbia isn’t found in the past but rather lies October 2020 for the FC2 ahead of us. That is especially true at this critical juncture in and in partnership with the the life of our city and country. Deputy Mayor for Planning and Economic Development. Their After facing a grave threat to our health and economic insights will drive our recovery stability in 2020, the coming distribution of a COVID-19 strategy. vaccine holds great promise in 2021. To better prepare for this next period, the FC2 convened the District Strong We are also grateful for the Economic Recovery Mini-Conference to advance a shared generous support from our understanding of our economic future. sponsors at Capital One, PNC Bank, United Bank, Boston Properties and Washington Gas. The Mini-Conference was FC2 joined with the Deputy Mayor for Planning and Economic a chance for us to draw on the best thinking in the District, Development (DMPED) and the D.C. -

Eagle Bancorp, Inc. Announces the Appointment of Kathy A

For Immediate Release February 16, 2018 EagleBank Contact Ronald D. Paul 301.986.1800 Eagle Bancorp, Inc. Announces the Appointment of Kathy A. Raffa to its Board of Directors BETHESDA, MD. Eagle Bancorp, Inc., (the “Company”) (NASDAQ: EGBN), the parent company of EagleBank (the “Bank”), today announced the appointment of Kathy A. Raffa to serve on the Board of Directors of Eagle Bancorp, Inc. Ms. Raffa has been serving as a director of the Bank’s board since March 2015. Ms. Raffa is the President of Raffa, PC, based in Washington, DC. It is one of the top 100 accounting firms in the nation. Ms. Raffa is a leader of this woman-owned accounting, consulting and technology firm, in which 12 of the 19 partners are women. She oversees client services for a wide range of nonprofit entities, and serves as an audit partner. She also leads a variety of aspects of the firm’s internal operations and business development. Prior to Raffa, PC, she spent the first 10 years of her career at Coopers & Lybrand (now PricewaterhouseCoopers). She has a CPA certificate from the District of Columbia and Maryland, and is a member of the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants. She currently serves as a trustee on several boards, including Trinity Washington University (where she chairs the Finance Committee and previously chaired the Audit Committee), the advisory board of Levine Music (where she was formerly the Board Chair), and the Federal City Council. Ms. Raffa holds a Bachelor of Science in Economics from the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania. -

Potential Effects of a Flat Federal Income Tax in the District of Columbia

S. HRG. 109–785 POTENTIAL EFFECTS OF A FLAT FEDERAL INCOME TAX IN THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA HEARINGS BEFORE A SUBCOMMITTEE OF THE COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED NINTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION SPECIAL HEARINGS MARCH 8, 2006—WASHINGTON, DC MARCH 30, 2006—WASHINGTON, DC Printed for the use of the Committee on Appropriations ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpoaccess.gov/congress/index.html U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 27–532 PDF WASHINGTON : 2007 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi, Chairman TED STEVENS, Alaska ROBERT C. BYRD, West Virginia ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico PATRICK J. LEAHY, Vermont CHRISTOPHER S. BOND, Missouri TOM HARKIN, Iowa MITCH MCCONNELL, Kentucky BARBARA A. MIKULSKI, Maryland CONRAD BURNS, Montana HARRY REID, Nevada RICHARD C. SHELBY, Alabama HERB KOHL, Wisconsin JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire PATTY MURRAY, Washington ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah BYRON L. DORGAN, North Dakota LARRY CRAIG, Idaho DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas RICHARD J. DURBIN, Illinois MIKE DEWINE, Ohio TIM JOHNSON, South Dakota SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas MARY L. LANDRIEU, Louisiana WAYNE ALLARD, Colorado J. KEITH KENNEDY, Staff Director TERRENCE E. SAUVAIN, Minority Staff Director SUBCOMMITTEE ON THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas, Chairman MIKE DEWINE, Ohio MARY L. LANDRIEU, Louisiana WAYNE ALLARD, Colorado RICHARD J. DURBIN, Illinois THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi (ex officio) ROBERT C. -

NEWS RELEASE Contact: Sherri Cunningham [email protected]

NEWS RELEASE Contact: Sherri Cunningham [email protected] 202-440-0954 Maura Brophy Named President and CEO of the NoMa Business Improvement District January 5, 2021 (Washington, DC) – The Board of Directors of the NoMa Business Improvement District (BID) announced today that Maura Brophy, current Director of Transportation and Infrastructure at the Federal City Council, has been named President and CEO of the NoMa BID. “We are excited to announce that Maura Brophy has agreed to serve as the new President and CEO of the NoMa BID,” said Brigg Bunker, Chairman of the NoMa BID Board of Directors and Managing Partner at Foulger-Pratt. “Maura is a talented and dynamic leader who has been engaged for many years in advocating to advance Washington, DC’s broad public interests, including the creation of affordable housing, supporting the region’s public transit system and improving public spaces. Her experience and collaborative leadership will help sustain and build upon the past success of the NoMa BID.” Maura is a respected urban planning professional with an impressive background in housing and community development, transportation and infrastructure. For the past five years, Maura has served in roles of increasing responsibility at the Federal City Council, the non-profit organization dedicated to the economic advancement of the District of Columbia, where her priority focus was promoting and supporting the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA), ensuring the successful redevelopment of Washington Union Station, and encouraging the adoption of efficient and effective policies related to new technology and new mobility. Prior to joining the Federal City Council, Maura worked in asset management for Community Preservation and Development Corporation (now Enterprise Community Development), a non-profit developer and owner of affordable housing in the Washington Metropolitan region, where she oversaw a portfolio of more than 2,000 multifamily residential units. -

CAPITAL REGION RAIL VISION from Baltimore to Richmond, Creating a More Unified, Competitive, Modern Rail Network

Report CAPITAL REGION RAIL VISION From Baltimore to Richmond, Creating a More Unified, Competitive, Modern Rail Network DECEMBER 2020 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 EXISTING REGIONAL RAIL NETWORK 10 THE VISION 26 BIDIRECTIONAL RUN-THROUGH SERVICE 28 EXPANDED SERVICE 29 SEAMLESS RIDER EXPERIENCE 30 SUPERIOR OPERATIONAL INTEGRATION 30 CAPITAL INVESTMENT PROGRAM 31 VISION ANALYSIS 32 IMPLEMENTATION AND NEXT STEPS 47 KEY STAKEHOLDER IMPLEMENTATION ROLES 48 NEXT STEPS 51 APPENDICES 55 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The decisions that we as a region make in the next five years will determine whether a more coordinated, integrated regional rail network continues as a viable possibility or remains a missed opportunity. The Capital Region’s economic and global Railway Express (VRE) and Amtrak—leaves us far from CAPITAL REGION RAIL NETWORK competitiveness hinges on the ability for residents of all incomes to have easy and Perryville Martinsburg reliable access to superb transit—a key factor Baltimore Frederick Penn Station in attracting and retaining talent pre- and Camden post-pandemic, as well as employers’ location Yards decisions. While expansive, the regional rail network represents an untapped resource. Washington The Capital Region Rail Vision charts a course Union Station to transform the regional rail network into a globally competitive asset that enables a more Broad Run / Airport inclusive and equitable region where all can be proud to live, work, grow a family and build a business. Spotsylvania to Richmond Main Street Station Relative to most domestic peer regions, our rail network is superior in terms of both distance covered and scope of service, with over 335 total miles of rail lines1 and more world-class service. -

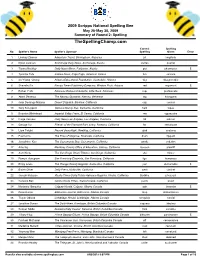

Round 2: Spelling Thespellingchamp.Com

2009 Scripps National Spelling Bee May 28-May 30, 2009 Summary of Round 2: Spelling TheSpellingChamp.com Correct Spelling No. Speller's Name Speller's Sponsor Spelling Given Error 1 Lindsey Zimmer Adventure Travel, Birmingham, Alabama jet longitude 2 Dylan Jackson Anchorage Daily News, Anchorage, Alaska sorites quarrel 3 Tianna Beckley Daily News-Miner, Fairbanks, Alaska got pharmecist E 4 Tynishia Tufu Samoa News, Pago Pago, American Samoa fun concise 5 So-Young Chung Arizona Educational Foundation, Scottsdale, Arizona wig disagreeable 6 Shevelle Six Navajo Times Publishing Company, Window Rock, Arizona red regamont E 7 Esther Park Arkansas Democrat Gazette, Little Rock, Arkansas nap promenade 8 Abeni Deveaux The Nassau Guardian, Nassau, Bahamas leg hexagonal 9 Juan Domingo Malana Desert Dispatch, Barstow, California cup census 10 Cory Klingsporn Ventura County Star, Camarillo, California ham topaz 11 Brandon Whitehead Imperial Valley Press, El Centro, California see oppressive 12 Paige Vasseur Daily News Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California lid pelican 13 George Liu Friends of the Diamond Bar Library, Pomona, California far reevaluate 14 Liam Twight Record Searchlight, Redding, California glad anatomy 15 Paul Uzzo The Press-Enterprise, Riverside, California drum flippant 16 Josephine Kao The Sacramento Bee, Sacramento, California syndic sedative 17 Amy Ng Monterey County Office of Education, Salinas, California laocoon plaintiff 18 Alex Wells The San Diego Union-Tribune, San Diego, California she mince 19 Ramya Auroprem San Francisco -

The Anacostia River Area and the City We Were Meant to Be

The Anacostia River Area and the City We Were Meant to Be The Anacostia River runs through our city, figuratively and literally separating our people...as Mayor, I will make restoring the Anacostia and the surrounding area a top economic development priority…I support plans that protect the Anacostia’s natural habitat and to make it available to all District residents. Tony Williams, summer 1998 Washington DC has always been a city like no other: planned, designed and built to be what today we would call “mission-driven.” In the second year of the French Revolution, French engineer Pierre Charles L’Enfant grandly designed America’s new capital to manifest the ideals of the American Revolution and the struggle for equality going on in his country. 223 years later, a brief walk on the National Mall conveys the unmistakable sense that the capital is meant to be a special place. But the harsh reality is that the nation’s capital has never really measured up to those lofty ideals. Beyond the monuments and federal veneer, it is a city painfully divided between haves and have-nots. For most of the last century, the Anacostia River and the immediate area around it have served as the District’s version of other cities’ infamous “tracks.” On the river’s west side are the National Mall and the magnificent monuments, the Capitol, White House and other federal government buildings, a vibrant downtown, beautiful parks, and several million dollar residential neighborhoods. More than 20 million tourists a year support local commerce. On the east side, there are a few pleasant middle-class neighborhoods, but no monuments, no grand buildings, and few tourists. -

The Business Issue

VOL. 52, NO. 06 • NOVEMBER 24 - 30, 2016 Don't Miss the WI Bridge Trump Seeks Apology as ‘Hamilton’ Cast Challenges Pence - Hot Topics/Page 4 The BusinessCenter Section Issue NOVEMBER 2016 | VOL 2, ISSUE 10 Protests Continue Ahead of Trump Presidency By Stacy M. Brown cles published on Breitbart, the con- WI Senior Writer servative news website he oversaw, ABC News reported. The fallout for African Americans, President Barack Obama, the na- Muslims, Latinos and other mi- tion's first African-American presi- norities over the election of Donald dent, said Trump had "tapped into Trump as president has continued a troubling strain" in the country to with ongoing protests around the help him win the election, which has nation. led to unprecedented protests and Trump, the New York business- even a push led by some celebrities man who won more Electoral Col- to get the electorate to change its vote lege votes than Democrat Hillary when the official voting takes place on Clinton in the Nov. 8 election, has Dec. 19. managed to make matters worse by A Change.org petition, which has naming former Breitbart News chief now been signed by more than 4.3 Stephen Bannon as his chief strategist. million people, encourages members Bannon has been accused by many of the Electoral College to cast their critics of peddling or being complicit votes for Hillary Clinton when the 5 Imam Talib Shareef of Masjid Muhammad, The Nation's Mosque, stands with dozens of Christians, Jewish in white supremacy, anti-Semitism leaders and Muslims to address recent hate crimes and discrimination against Muslims during a news conference and sexism in interviews and in arti- TRUMP Page 30 before daily prayer on Friday, Nov. -

ED350369.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 350 369 UD 028 888 TITLE Introducing African American Role Models into Mathematics and Science Lesson Plans: Grades K-6. INSTITUTION American Univ., Washington, DC. Mid-Atlantic Equity Center. SPONS AGENCY Department of Education, Washington, DC. PUB DATE 92 NOTE 313p. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher)(052) Collected Works General (020) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Biographies; *Black Achievement; Black History; Black Students; *Classroom Techniques; Cultural Awareness; Curriculum Development; Elementary Education; Instructional Materials; Intermediate Grades; Lesson Plans; *Mathematics Instruction; Minority Groups; *Role Models; *Science Instruction; Student Attitudes; Teaching Guides IDENfIFIERS *African Americans ABSTRACT This guide presents lesson plans, with handouts, biographical sketches, and teaching guides, which show ways of integrating African American role models into mathematics and science lessons in kindergarten through grade 6. The guide is divided into mathematics and science sections, which each are subdivided into groupings: kindergarten through grade 2, grades 3 and 4, and grades 5 and 6. Many of the lessons can be adjusted for other grade levels. Each lesson has the following nine components:(1) concept statement; (2) instructional objectives;(3) male and female African American role models;(4) affective factors;(5) materials;(6) vocabulary; (7) teaching procedures;(8) follow-up activities; and (9) resources. The lesson plans are designed to supplement teacher-designed and textbook lessons, encourage teachers to integrate black history in their classrooms, assist students in developing an appreciation for the cultural heritage of others, elevate black students' self-esteem by presenting positive role models, and address affective factors that contribute to the achievement of blacks and other minority students in mathematics and science. -

Secretary Buttigieg

June 15, 2021 The Honorable Pete Buttigieg U.S. Department of Transportation 1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE Washington, DC 20590 Dear Secretary Buttigieg, As representatives of more than one hundred businesses and nonprofits from the Metropolitan Washington region, we write to you today to thank you for your commitment to furthering our nation's rich legacy of innovative investments in transportation and infrastructure with the Amer- ican Jobs Plan. As the administration and Congress seek to spur investments in transportation and infrastructure, we urge you to support funding the $10.7 billion Washington Union Station Expansion Project (SEP). As Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority’s (WMATA) and Maryland Area Regional Commuter’s (MARC) busiest station and the Virginia Railway Express’s (VRE) second busiest, Union Station requires immediate investments for its expansion and redevelopment. Serving over 100,000 passengers each day, Washington Union Station is the heart of the Nation’s Capital and the gateway to the most heavily used rail corridor in the Western hemisphere. Over the next dec- ade, ridership volumes on Amtrak, MARC, and VRE are estimated to reach two or three times their pre-pandemic levels. Despite its central and essential role, the station has not seen any in- frastructure improvements since the 1990s. It has a dangerous backlog of deferred maintenance that presents significant ADA access, safety, and security issues. Without a serious upgrade, it will struggle to handle riders—and deliver national, regional, and local economic benefits. This year the Federal Railroad Administration, in collaboration with Amtrak and the Union Station Redevelopment Corporation, will unveil the ten-year, $10.7 billion Washington Union Station Ex- pansion Project (SEP) to modernize facilities and create a world-class multimodal transit hub.