Lives of the Conjurers Volume Three by P Rofessor Solo Mon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Lawyer Presents the Case for the Afterlife

A Lawyer Presents the Case for the Afterlife Victor James Zammit 2 Acknowledgements: My special thanks to my sister, Carmen, for her portrait of William and to Dmitri Svetlov for his very kind assistance in editing and formatting this edition. My other special thanks goes to the many afterlife researchers, empiricists and scientists, gifted mediums and the many others – too many to mention – who gave me, inspiration, support, suggestions and feedback about the book. 3 Contents 1. Opening statement............................................................................7 2. Respected scientists who investigated...........................................12 3. My materialization experiences....................................................25 4. Voices on Tape (EVP).................................................................... 34 5. Instrumental Trans-communication (ITC)..................................43 6. Near-Death Experiences (NDEs) ..................................................52 7. Out-of-Body Experiences ..............................................................66 8. The Scole Experiment proves the Afterlife ................................. 71 9. Einstein's E = mc2 and materialization.........................................77 10. Materialization Mediumship.......................................................80 11. Helen Duncan................................................................................90 12. Psychic laboratory experiments..................................................98 13. Observation -

Witch, Warlock, and Magician, by 1

Witch, Warlock, and Magician, by 1 Witch, Warlock, and Magician, by William Henry Davenport Adams This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Witch, Warlock, and Magician Historical Sketches of Magic and Witchcraft in England and Scotland Author: William Henry Davenport Adams Release Date: February 4, 2012 [EBook #38763] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK WITCH, WARLOCK, AND MAGICIAN *** Produced by Irma äpehar, Sam W. and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.) Transcriber's Note Greek text has been transliterated and is surrounded with + signs, e.g. +biblos+. Characters with a macron (straight line) above are indicated as [=x], where x is the letter. Witch, Warlock, and Magician, by 2 Characters with a caron (v shaped symbol) above are indicated as [vx], where x is the letter. Superscripted characters are surrounded with braces, e.g. D{ni}. There is one instance of a symbol, indicated with {+++}, which in the original text appeared as three + signs arranged in an inverted triangle. WITCH, WARLOCK, AND MAGICIAN Historical Sketches of Magic and Witchcraft in England and Scotland BY W. H. DAVENPORT ADAMS 'Dreams and the light imaginings of men' Shelley J. W. BOUTON 706 & 1152 BROADWAY NEW YORK 1889 PREFACE. -

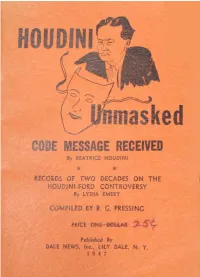

CODE MESSAGE RECEIVED by BEATRICE HOUDINI

CODE MESSAGE RECEIVED By BEATRICE HOUDINI RECORDS OF TWO DECADES ON THE HOUDINI-FORD CONTROVERSY By LYDIA EMERY COMPILED BY R. C. PRESSING PRICE ONE—DOLLAR Published By DALE NEWS, Inc., LILY DALE, N. Y. 19 4 7 fiamphktiu curuL fiookkdA. WHAT DOES SPIRITUALISM ACTUALLY TEACH? By Sir Arthur Conan Doyle .......... ........................ ~...50c TRUM PET M ED IU M SH IP; How To Develop It By Clifford Bias ...-.............................—.................. ......... .$1.00 WHY RED INDIANS ARE SPIRIT GUIDES By Frederic Harding ...................... .................. ......... .......... .... 25c THE CATECHISM OF SPIRITUAL PHILOSOPHY By W. Jj Colville ................................................. .................50c THE PHILOSOPHY OF DEATH: Death Explained By Andrew Jackson Davis ................................ _....... 50c THE BLUE ISLAND: A Vivid Account of Life in the SPIRIT WORLD By William T. Stead...... ..... ........... ....................... ........... .$1.50 A GUIDE T O M ED IU M SH IP; Dictated by a materialized spirit through the mediumship of William W. Aber ......— ----------- ------------- --------- 50c SPIRITUALISM RECOGNIZED AS A SCIENCE: The Reality of The Spirit ual World by Oliver Lodge ...........................—....... ... ....... $1.00 RAPPINCS THAT STARTLED THE WORLD— Facts about The Fox Sisters: compiled by R. G. Pressing .................................................$1.00 HOW I K N O W THE DEAD RETURN by England’s greatest Spiritualist. W. T. Stead ..................... .......... ............. ... -

Flash Paper Feb 2020 (Pdf)

The Flash Paper February, 2020 Bob Gehringer, Editor Presidential Ponderings Introduction: The Effect Our own member, Theron Christensen's first book “To produce a magical effect, of original conception, is Plotting Astonishment has just a work of high art.” --Nevil Maskelyne been published and is now Dear reader, I hold my breath as you turn the available on Amazon. It was pages of this book for the first time. I was hesitant to add good for me to read it. I plan to this work to the vast cacophony of magic literature. I am read it again. I believe the not well-known among magicians, nor do I pretend to be insights he shares has the power any sort of expert; and to publish your knowledge and to raise your own performances opinion is to invite the scorn and rebuttal of many. But to yet another level. With his permission, I share a too many of my close friends and the nudge of my portion of the book's introduction with you. conscience have pushed me to produce the work which you hold in your hands. To start out, I would like to explain my intentions. When Maskelyne and Devant published Our Magic in 1911, they urged magicians to recognize the importance of being original in magic. “Without originality,” they said, “no man can become a great artist.” Their efforts paid off. Today, magicians almost universally accept the importance of originality. Just as Maskelyne observed over one hundred years ago, magicians tend to seek after originality in one of three ways. -

CATALOGUE 217: Animisme Et Spiritisme

Animisme et Spiritisme Medical History Alternative Remedies Medical Oddities, Curiosities Pathology Spiritualism & Apparitions Ghosts & Seances & Breaking Societal Norms Library of Phillip K. Wilson Catalogue 217 JEFF WEBER RARE BOOKS Carlsbad, California ALL BOOKS WITH PICTURES AT: JEFFWEBERRAREBOOKS.COM Ordering instructions at rear The library of Phillip K. Wilson [part 1] 1000 ABBOTT, David P. (1863-1934). Behind the Scenes with the Mediums. Chicago: Open Court, 1916. ¶ Small 8vo. [2], vi, 340 pp. Index. Original wrappers; spine worn, small tear to upper corner of ffep. Bold ownership signature on title of Jean Peters; multiple institutional rubber-stamps. Good. $ 20 Fifth revised (and expanded) edition. Abbott was a magician, author, and professional skeptic, and friend of Houdini. He is perhaps best-remembered for his debunking of various mediums, many of which are described in this volume, his bestselling work. 1001 ACKERKNECHT, Erwin H. (1906-1988). History and Geography of the Most Important Diseases. New York: Hafner, 1972. ¶ Reprint of 1965 edition. 8vo. xii, [2], 210 pp. 13 maps & charts, index. Original black gilt-stamped cloth. Very good. $ 32 Ackerknecht first came to prominence as a Trotskyist in pre-Nazi Germany. After fleeing to America in the 30’s he turned his attention to the History of Medicine. He eventually became one of the most influential medical historians in the world, becoming the inaugural chair of the history of medicine department at the University of Wisconsin. 1002 ACKERKNECHT, Erwin H. (1906-1988). Malaria in the Upper Mississippi Valley, 1760-1900. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1945. ¶ Series: Supplements to the Bulletin of the History of Medicine, no. -

Primitive Religion

CO 00 m<OU 166273 >m Q&MANIA UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Call No:7^<9^ 53 P Accession No, %$ Tfcis book should be returned on or before the date last marked PRIMITIVE RELIGION PRIMITIVE RELIGION BY ROBERT H. LOWIE, PH. D. ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF ANTHROPOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA ; ' ' AUTHOR OF Primitive Society LONDON GEORGE ROUTLEDGE AND SONS, LTD. BROADWAY HOUSE : 68-74, CARTER LANE, E.G. 1936 Printed in Great Britain by MACKAYB LTD., Chatham > PREFACE THIS work does not purport to be a handbook of either the theories broached on the subject of primitive religion or of the ethnographic data described in hundreds of accessible mono- graphs. My purpose is to provide an introduction to further study in which other than the traditional topics shall assume a place of honor. On the other hand I have taken pains to re- duce to a minimum the discussion of theories that have been more than amply treated by previous writers. The mode of approach will be found to differ fundamentally from that of my book on Primitive Society. The reason lies in the quite different status of the two subjects at the present time. In the field of primitive sociology it seemed desirable to marshal the evidence against the indefensible neglect of histori- cal considerations that persists in some quarters. In the study of comparative religion it is the psychological point of view that and however be for requires emphasis ; important history may an elucidation of psychology, its part is ancillary. By con- sistently stressing the psychological aspects of primitive religion I hope to have contributed something to a closer alliance of two sister sciences that too frequently have pursued their paths in mutual neglect. -

The Magic Gang’ Unit to Deceive German Field Marshal Rommel with Fake Tanks, Railway Lines Etc

In WW II, A British Illusionist Formed ‘The Magic Gang’ Unit To Deceive German Field Marshal Rommel With Fake Tanks, Railway Lines Etc. National Magic Day each year on October 31st recognizes the thrill of seeing the performance art. It takes place during National Magic Week. One of the most renowned magicians was Harry Houdini. Known for his *escapology, Houdini had developed a range of stage magic tricks and made full use of the variety of conjuring techniques, including fake equipment and collusion with individuals in the audience. His show business savvy was as exceptional as his showmanship. Magic Day started with a “Houdini Day”, the first of which took place in the summer of 1927, less than one year after the famous magician’s death. His wife presented a trophy in honour of him on that day. Houdini died at 1:26pm on October 31st, 1926. The Houdini Museum is located in Scranton, Pennsylvania. Some magic categories: Stage illusions –a kind of large scale performance on a stage. Parlor magic – a performance before a medium scale audience such as an auditorium. Micromagic – performed close up using coins, cards, and other small items. It’s also known as close-up or table magic. This type of performance occurs in an intimate setting. Escapology – In this type of performance, the artist escapes from a dangerous situation such as being submerged underwater while handcuffed or dangling from a burning rope. Pickpocket magic – A distraction type of performance, the artist, makes watches, jewelry, wallets, and more disappear through misdirection. The audience witnesses the entire event. -

The Art of Memory

FRANCES YATES Selected Works Volume III The Art of Memory London and New York FRANCES YATES Selected Works VOLUME I The Valois Tapestries VOLUME II Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition VOLUME III The Art of Memory VOLUME IV The Rosicrucian Enlightenment VOLUME V Astraea VOLUME VI Shakespeare's Last Plays VOLUME VII The Occult Philosophy in the Elizabethan Age VOLUME VIII Lull and Bruno VOLUME IX Renaissance and Reform: The Italian Contribution VOLUME X Ideas and Ideals in the North European Renaissance First published 1966 by Routledge & Kcgan Paul Reprinted by Routledge 1999 11 New Fetter Lane London EC4I' 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Croup © 1966 Frances A. Yates Printed and bound in Great Britain by Antony Rowe Ltd, Chippenham, Wiltshire Publisher's note The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original book may be apparent. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A CIP record of this set is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book has been requested ISBN 0-415-22046-7 (Volume 3) 10 Volumes: ISBN 0-415-22043-2 (Set) Hermetic Silence. From Achilles Bocchius, Symbolicarum quaestionum . libri quinque, Bologna, 1555. Engraved by G. Bonasone (p. 170) FRANCES A.YATES THE ART OF MEMORY ARK PAPERBACKS London, Melbourne and Henley First published in 1966 ARK Edition 1984 ARK PAPERBACKS is an imprint of Routledgc & Kcgan Paul plc 14 Leicester Square, London WC2II 7PH, Kngland. -

Magic Roadshow 71-80

Magic Roadshow May 15th, 2007 Issue # 71 Rick Carruth / editor (C)2007 All Rights Reserved Worldwide Street Magic's #1 free newsletter for magicians, street performers, restaurant workers, close-up artists, and mentalists, with subscribers in over 72 countries worldwide. _/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/ Hi All Welcome to another issue of the Magic Roadshow. All you guys and ladies who have signed up since our last issue are wished a special "Hello and Welcome". I hope you will find something here that will keep you coming back issue after issue.. I don't say it often enough, but I want to take a moment and thank too all you great folks who email me from time to time with your thoughts and comments. It means alot to me for you to take time out of your day to share your thoughts.. Without bragging, I've heard over and over how much you enjoy the Roadshow, or how much you appreciate my efforts. And I'm honestly humbled that you find some form of pleasure in my little experiment in magic communication. Although I formerly responded to emails in a matter of a few hours, it may now take several days for me to get back to you. It's not that I'm too busy, it's that I'm just busy enough that I can't respond to emails the way I want to every single night. -

Special Issue #6 Christmas 2020 Hello Friends... I

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- MAGIC ROADSHOW - Special Issue #6 Christmas 2020 Hello Friends... I almost hated to use the year 2020 on this issue. It would be so easy to wait a month and have the honor of publishing in 2021 instead. What a booger of a year.. That said.. I am glad to still be here. 2020 has changed the world of magic. We are performing in ways we would never have thought possible only months ago. Zoom... what the heck is a Zoom? Everyone knows now. I am SO looking forward to things going back to normal. And while I’m at it… Elections ?? I was so sick of the political ads they could have elected Hannibal Lecter and I would have done cart wheels.. My gosh... Enough already... I intended to get this issue out about May. Between the pandemic, tremendous demands from my other job on account of the pandemic.. and some personal aggravation.. this was the best I could do. In the midst of the pandemic my right eye, my good eye, hemorrhage from a small vessel that was growing where it shouldn't. I couldn't get all the prompt treatment I would normally get on account of shut downs. Normally, the doctor could go in and vacuum out the blood.. but ALL non-life threatening surgeries were postponed. That meant waiting months for the blood to dissipate on its own. Not being able to see my computer screen without a magnifying glass was a royal pain in the ass... excuse my French. And on top of that, my wife, Carolyn, developed breast cancer.. -

The Dying God Title Page (Required) the Dying God

Half Title Page (required) The Dying God Title Page (required) The Dying God The Hidden History of Western Civilization David Livingstone Copyright Page (required) All Rights Reserved. Copyright © 2000 David Livingstone No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping or by any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the publisher. Published by Writers Club Press For information, please contact: iUniverse.com 5220 South 16th Street Suite 200 Lincoln, NE 68512-1274 (Click here to input any legal disclaimers or credits, if any.) ISBN: 1-58348-XXX-X Printed in the United States of America Table of Contents (optional) Introduction Chapter 1: The Sons of God Chapter 2: Venus Chapter 3: Baal Chapter 4: Hercules Chapter 5: Prometheus Chapter 6: Dionysus Chapter 7: Apollo Chapter 8: Enoch Chapter 9: Mithras Chapter 10: Logos Chapter 11: Thoth Chapter 12: Seth Chapter 13: Idris Chapter 14: Metratron Chapter 15: Baphomet Chapter 16: Percival Chapter 17: Hermes Chapter 18: Hiram Chapter 19: Lucifer Introduction (optional) Western Civilization Few would acknowledge, given the state of our society’s technological advance, that our understanding of history could be significantly inaccurate. The problem is that, due to a general lack of knowledge of the accomplishments of other civilizations, the history of Western civilization, presumed to have begun in Greece, progressed through Rome and culminated in modern Europe and America, is confused with the history of the world. While certain achievements are recognized for other cultures, the West is believed to have not only dominated modern history, but all of history, and therefore, has been the single greatest contributor of the accomplishments that have benefited mankind. -

Ffi Magicurrents W San Die

ffi Magicurrents W San Die Honest Sid Gerhart Rine 76 Volume XV No 11 November 200L October Was Magic Month In San Diego and Ring 76! October was an important month for Ring 76 and its putting the finishing touches on the early planning for next members. This past month we learned that veteran July's 74'h IBM Convention. magician Bev Bergeron has been added to the list of performers presenting a special hourJong stand-up program David's outgoing personality and love of magic was a very at the IBM Convention next summer here in San Diego. welcome addition to our evening of fellowship and entertaining. We look forward to having him back in Bev has been a longtime friend of Ring 76 going back to his January for the convention committee meeting. days in San Diego during this cities 200'h Anniversary and the series of shows he presented in Oldtown during the summer of We were able to meet Maco Ruly a professional magician 1969. He was a mentor to San Diego magician Bob Sheets and and puppeteer from helped him get his start in show business. Mexico who was attending our meeting Bev will arrive a few to watch his friend days before the 2002 r Armando Torres do his Convention and present a : act for our ring lecture for Ring 76 on : program. Both July 2"d. This is a rare 1 gentlemen were treat because he will not i welcome guests and be doing his lecture at ' we look forward to this year's convention.