Zoom Melies Va

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hugo Study Notes

Hugo Directed by: Martin Scorsese Certificate: U Country: USA Running time: 126 mins Year: 2011 Suitable for: primary literacy; history (of cinema); art and design; modern foreign languages (French) www.filmeducation.org 1 ©Film Education 2012. Film Education is not responsible for the content of external sites SYNOPSIS Based on a graphic novel by Brian Selznick, Hugo tells the story of a wily and resourceful orphan boy who lives with his drunken uncle in a 1930s Paris train station. When his uncle goes missing one day, he learns how to wind the huge station clocks in his place and carries on living secretly in the station’s walls. He steals small mechanical parts from a shop owner in the station in his quest to unlock an automaton (a mechanical man) left to him by his father. When the shop owner, George Méliès, catches him stealing, their lives become intertwined in a way that will transform them and all those around them. www.hugomovie.com www.theinventionofhugocabret.com TeacHerS’ NOTeS These study notes provide teachers with ideas and activity sheets for use prior to and after seeing the film Hugo. They include: ■ background information about the film ■ a cross-curricular mind-map ■ classroom activity ideas – before and after seeing the film ■ image-analysis worksheets (for use to develop literacy skills) These activity ideas can be adapted to suit the timescale available – teachers could use aspects for a day’s focus on the film, or they could extend the focus and deliver the activities over one or two weeks. www.filmeducation.org 2 ©Film Education 2012. -

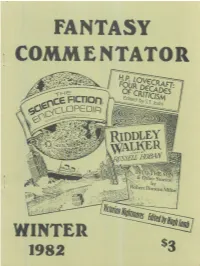

Fantasy Commentator EDITOR and PUBLISHER: CONTRIBUTING EDITORS: A

Fantasy Commentator EDITOR and PUBLISHER: CONTRIBUTING EDITORS: A. Langley Searles Lee Becker, T. G. Cockcroft, 7 East 235th St. Sam Moskowitz, Lincoln Bronx, N. Y. 10470 Van Rose, George T. Wetzel Vol. IV, No. 4 -- oOo--- Winter 1982 Articles Needle in a Haystack Joseph Wrzos 195 Voyagers Through Infinity - II Sam Moskowitz 207 Lucky Me Stephen Fabian 218 Edward Lucas White - III George T. Wetzel 229 'Plus Ultra' - III A. Langley Searles 240 Nicholls: Comments and Errata T. G. Cockcroft and 246 Graham Stone Verse It's the Same Everywhere! Lee Becker 205 (illustrated by Melissa Snowind) Ten Sonnets Stanton A. Coblentz 214 Standing in the Shadows B. Leilah Wendell 228 Alien Lee Becker 239 Driftwood B. Leilah Wendell 252 Regular Features Book Reviews: Dahl's "My Uncle Oswald” Joseph Wrzos 221 Joshi's "H. P. L. : 4 Decades of Criticism" Lincoln Van Rose 223 Wetzel's "Lovecraft Collectors Library" A. Langley Searles 227 Moskowitz's "S F in Old San Francisco" A. Langley Searles 242 Nicholls' "Science Fiction Encyclopedia" Edward Wood 245 Hoban's "Riddley Walker" A. Langley Searles 250 A Few Thorns Lincoln Van Rose 200 Tips on Tales staff 253 Open House Our Readers 255 Indexes to volume IV 266 This is the thirty-second number of Fantasy Commentator^ a non-profit periodical of limited circulation devoted to articles, book reviews and verse in the area of sci ence - fiction and fantasy, published annually. Subscription rate: $3 a copy, three issues for $8. All opinions expressed herein are the contributors' own, and do not necessarily reflect those of the editor or the staff. -

The Coming of Sound Film and the Origins of the Horror Genre

UNCANNY BODIES UNCANNY BODIES THE COMING OF SOUND FILM AND THE ORIGINS OF THE HORROR GENRE Robert Spadoni UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS BERKELEY LOS ANGELES LONDON University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more informa- tion, visit www.ucpress.edu. A previous version of chapter 1 appeared as “The Uncanny Body of Early Sound Film” in The Velvet Light Trap 51 (Spring 2003): 4–16. Copyright © 2003 by the University of Texas Press. All rights reserved. The cartoon on page 122 is © The New Yorker Collection 1999 Danny Shanahan from cartoonbank.com. All rights reserved. University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 2007 by The Regents of the University of California Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Spadoni, Robert. Uncanny bodies : the coming of sound film and the origins of the horror genre / Robert Spadoni. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978-0-520-25121-2 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn 978-0-520-25122-9 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Horror films—United States—History and criticism. 2. Sound motion pictures—United States— History and criticism. I. Title. pn1995.9.h6s66 2007 791.43'6164—dc22 2006029088 Manufactured in the United States -

Comedies Produced by Hal Roach, It Presents Their Funniest and Most Famous Comedies 640-02-0040, 16Mm

,r, ~ Winter 1973-4 ., WEEP 'v,i •._~~ H .,,1$>-~on The Eastin-Phelan Corporation Davenport, Iowa 52808 orld's largest ,election of ·· t ings to snow" l i tc,;Bl ackhawk's Guarantee BERTH MARKS THE PRINCE OF PEP (1929) (1925) We want you to be satisfied with (abridged!_ what you buy from Blackhawk starring STAN LAUREL and OLIVER HARDY starring RICHARD TALMADGE if, after receiving an item you Stan and Ollie are a "big time" vaudeville team enroute from one theatre to another are disappointed in any way, re ,n the upper berth of an open section Pullman. While the space is confined, the laughs with Brindley Shaw, Nola Luxford, Joe Harrjngton are not, and this one has some great moments. turn it to us transportation pre A fashionable physician, Dr. James Leland caught his secretary stealing drugs and in paid. in ,ts original condition, SOUND VERSIONS the ensuing struggle, lost his memory from a blow on the head. Shortly after, a mys• and within ten days after you 830-02-1100, Standard 8mm., magnetic sound, 375-feet, 14-ozs . $24.98 terious figure known only as The Black X stepped forth to fight the war on crime ar.d receive it, and we 'll allow you drug peddlers. 880--02-1100, Super 8, magnetic sound, 400-feet, 14-ozs ....... $26.98 It's all here-the fabulous Richard Talmadge in one of his amaz,ng adventure feats. full credit on some other pur 640-02-1100, 16mm., optical sound, 750-feet, 3-lbs . ....... .. $44.98 A professional abridgement from a 5-reel feature of 1925, Blackhawk's version of The chase. -

The Creative Process

The Creative Process THE SEARCH FOR AN AUDIO-VISUAL LANGUAGE AND STRUCTURE SECOND EDITION by John Howard Lawson Preface by Jay Leyda dol HILL AND WANG • NEW YORK www.johnhowardlawson.com Copyright © 1964, 1967 by John Howard Lawson All rights reserved Library of Congress catalog card number: 67-26852 Manufactured in the United States of America First edition September 1964 Second edition November 1967 www.johnhowardlawson.com To the Association of Film Makers of the U.S.S.R. and all its members, whose proud traditions and present achievements have been an inspiration in the preparation of this book www.johnhowardlawson.com Preface The masters of cinema moved at a leisurely pace, enjoyed giving generalized instruction, and loved to abandon themselves to reminis cence. They made it clear that they possessed certain magical secrets of their profession, but they mentioned them evasively. Now and then they made lofty artistic pronouncements, but they showed a more sincere interest in anecdotes about scenarios that were written on a cuff during a gay supper.... This might well be a description of Hollywood during any period of its cultivated silence on the matter of film-making. Actually, it is Leningrad in 1924, described by Grigori Kozintsev in his memoirs.1 It is so seldom that we are allowed to study the disclosures of a Hollywood film-maker about his medium that I cannot recall the last instance that preceded John Howard Lawson's book. There is no dearth of books about Hollywood, but when did any other book come from there that takes such articulate pride in the art that is-or was-made there? I have never understood exactly why the makers of American films felt it necessary to hide their methods and aims under blankets of coyness and anecdotes, the one as impenetrable as the other. -

The Old and the New Magic

E^2 CORNELL UNIVERSITY gilBRARY . GIFT OF THE AUTHOR Digitized by Microsoft® T^^irt m4:£±z^ mM^^ 315J2A. j^^/; ii'./jvf:( -UPHF ^§?i=£=^ PB1NTEDINU.S.A. Library Cornell University GV1547 .E92 Old and the new maj 743 3 1924 029 935 olin Digitized by Microsoft® This book was digitized by Microsoft Corporation in cooperation witli Cornell University Libraries, 2007. You may use and print this copy in limited quantity for your personal purposes, but may not distribute or provide access to it (or modified or partial versions of it) for revenue-generating or other commercial purposes. Digitized by Microsoft® Digitized by Microsoft® Digitized by Microsoft® Digitized by Microsoft® ROBERT-KCUIUT Digitized by Microsoft® THE OLDUI^DIMEJ^ MAGIC BY HENRY RIDGELY EVANS INTRODUCTION E1^ k -io^s-ji, Copyright 1906 BY The Open Court Publishing Co. Chicago -J' Digitized by Microsoft® \\\ ' SKETCH OF HENRY RIDGELY EVAXS. "Elenry Ridgely Evans, journalist, author and librarian, was born in Baltimore, ^Md., Xovember 7, 1861. He is the son 01 Henry Cotheal and Alary (Garrettson) Evans. Through his mother he is descended from the old colonial families of Ridgely, Dorsey, AA'orthington and Greenberry, which played such a prominent part in the annals of early Maryland. \h. Evans was educated at the preparatory department of Georgetown ( D. C.) College and at Columbian College, Washington, D. C He studied law at the University of Maryland, and began its practice in Baltimore City ; but abandoned the legal profession for the more congenial a\'ocation <jf journalism. He served for a number of }ears as special reporter and dramatic critic on the 'Baltimore N'ews,' and subsequently became connected with the U. -

Witch, Warlock, and Magician, by 1

Witch, Warlock, and Magician, by 1 Witch, Warlock, and Magician, by William Henry Davenport Adams This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Witch, Warlock, and Magician Historical Sketches of Magic and Witchcraft in England and Scotland Author: William Henry Davenport Adams Release Date: February 4, 2012 [EBook #38763] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK WITCH, WARLOCK, AND MAGICIAN *** Produced by Irma äpehar, Sam W. and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.) Transcriber's Note Greek text has been transliterated and is surrounded with + signs, e.g. +biblos+. Characters with a macron (straight line) above are indicated as [=x], where x is the letter. Witch, Warlock, and Magician, by 2 Characters with a caron (v shaped symbol) above are indicated as [vx], where x is the letter. Superscripted characters are surrounded with braces, e.g. D{ni}. There is one instance of a symbol, indicated with {+++}, which in the original text appeared as three + signs arranged in an inverted triangle. WITCH, WARLOCK, AND MAGICIAN Historical Sketches of Magic and Witchcraft in England and Scotland BY W. H. DAVENPORT ADAMS 'Dreams and the light imaginings of men' Shelley J. W. BOUTON 706 & 1152 BROADWAY NEW YORK 1889 PREFACE. -

Science Fiction Films of the 1950S Bonnie Noonan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 "Science in skirts": representations of women in science in the "B" science fiction films of the 1950s Bonnie Noonan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Noonan, Bonnie, ""Science in skirts": representations of women in science in the "B" science fiction films of the 1950s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3653. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3653 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. “SCIENCE IN SKIRTS”: REPRESENTATIONS OF WOMEN IN SCIENCE IN THE “B” SCIENCE FICTION FILMS OF THE 1950S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English By Bonnie Noonan B.G.S., University of New Orleans, 1984 M.A., University of New Orleans, 1991 May 2003 Copyright 2003 Bonnie Noonan All rights reserved ii This dissertation is “one small step” for my cousin Timm Madden iii Acknowledgements Thank you to my dissertation director Elsie Michie, who was as demanding as she was supportive. Thank you to my brilliant committee: Carl Freedman, John May, Gerilyn Tandberg, and Sharon Weltman. -

Film and Modernity (Paris Version) | University of Kent

09/25/21 Film and Modernity (Paris version) | University of Kent Film and Modernity (Paris version) View Online This module investigates the relationship between film, modernity and modernism through the analysis of the works and career of Jean-Luc Godard, whose oeuvre can be largely defined by a desire to challenge the traditional boundaries between film and reality, fiction and documen-tary, autobiography and history, and film theory and film practice. In addition to being a pro-tagonist in the launching of a film movement preoccupied with the “here and now” of French society, Godard has engaged with a number of trends in film criticism and film theory. The analysis of his works will therefore allow for an examination of a number of questions that have defined the study of film, from auteurism to a more interdisciplinary approach to the cin-ema, from Bazin to Eisenstein, from filmmaking as sociology to filmmaking as self-investigation. [1] Abel, R. 2000. Discourse, narrative, and the subject of capital: Marcel L’Herbier’s L’Argent. French film: texts and contexts. Routledge. 37–50. [2] Abel, R. 1984. The Alternate Cinema Network, Paris qui dort. French cinema: the first wave, 1915-1929. Princeton U.P. 241–275 and 377–80. [3] Abel, Richard 1996. Booming the Film Business: The Historical Specificity of Early French Cinema. Silent film. Athlone. 109–124. [4] Abel, Richard 1988. Photogénie and Company. French film theory and criticism: a 1/14 09/25/21 Film and Modernity (Paris version) | University of Kent history/anthology, 1907-1939. Princeton U.P. 95–124. -

Dystopian Science Fiction Cinema In

Between the Sleep and the Dream of Reason: Dystopian Science Fiction Cinema In 1799, Francisco Goya published Los Caprichos, a collection of eighty aquatinted etchings satirising “the innumerable foibles and follies to be found in any civilized society, and … the common prejudices and deceitful practices which custom, ignorance, or self-interest have made usual.”i The most famous of them, “Capricho 43,” depicts a writer, slumped on his desk, while behind him strange creatures – a large cat, owls that shade into bats – emerge from the encompassing gloom. It is called “El sueño de la razón produce monstrous,” which is usually translated as “the sleep of reason produces monsters,” but could as easily be rendered “the dream of reason produces monsters.” In that ambiguous space – between reason’s slumber unleashing unreason and reason becoming all that there is – dystopia lies. In 1868, John Stuart Mill coined the word “dystopia” in a parliamentary speech denouncing British government policy in Ireland. Combining the Greek dys (bad) and topos (place), it plays on Thomas More’s “utopia,” itself a Greek pun: “ou” plus “topos” means “nowhere,” but “ou” sounds like “eu,” which means “good,” so the name More gave to the island invented for his 1516 book, Utopia, suggests that it is also a “good place.” It remains unclear whether More actually intended readers to consider his imaginary society, set somewhere in the Americas, as better than 16th century England. But it is certainly organized upon radically different lines. Private property and unemployment (but not slavery) have been abolished. Communal dining, legalized euthanasia, simple divorces, religious tolerance and a kind of gender equality have been introduced. -

Best Picture of the Yeari Best. Rice of the Ear

SUMMER 1984 SUP~LEMENT I WORLD'S GREATEST SELECTION OF THINGS TO SHOW Best picture of the yeari Best. rice of the ear. TERMS OF ENDEARMENT (1983) SHIRLEY MacLAINE, DEBRA WINGER Story of a mother and daughter and their evolving relationship. Winner of 5 Academy Awards! 30B-837650-Beta 30H-837650-VHS .............. $39.95 JUNE CATALOG SPECIAL! Buy any 3 videocassette non-sale titles on the same order with "Terms" and pay ONLY $30 for "Terms". Limit 1 per family. OFFER EXPIRES JUNE 30, 1984. Blackhawk&;, SUMMER 1984 Vol. 374 © 1984 Blackhawk Films, Inc., One Old Eagle Brewery, Davenport, Iowa 52802 Regular Prices good thru June 30, 1984 VIDEOCASSETTE Kew ReleMe WORLDS GREATEST SHE Cl ION Of THINGS TO SHOW TUMBLEWEEDS ( 1925) WILLIAMS. HART William S. Hart came to the movies in 1914 from a long line of theatrical ex perience, mostly Shakespearean and while to many he is the strong, silent Western hero of film he is also the peer of John Ford as a major force in shaping and developing this genre we enjoy, the Western. In 1889 in what is to become Oklahoma Territory the Cherokee Strip is just a graz ing area owned by Indians and worked day and night be the itinerant cowboys called 'tumbleweeds'. Alas, it is the end of the old West as the homesteaders are moving in . Hart becomes involved with a homesteader's daughter and her evil brother who has a scheme to jump the line as "sooners". The scenes of the gigantic land rush is one of the most noted action sequences in film history. -

Georges Méliès: Impossible Voyager

Georges Méliès: Impossible Voyager Special Effects Epics, 1902 – 1912 Thursday, May 15, 2008 Northwest Film Forum, Seattle, WA Co-presented by The Sprocket Society and the Northwest Film Forum Curated and program notes prepared by Spencer Sundell. Special music presentations by Climax Golden Twins and Scott Colburn. Poster design by Brian Alter. Projection: Matthew Cunningham. Mr. Sundell’s valet: Mike Whybark. Narration for The Impossible Voyage translated by David Shepard. Used with permission. (Minor edits were made for this performance.) It can be heard with a fully restored version of the film on the Georges Méliès: First Wizard of Cinema (1896-1913) DVD box set (Flicker Alley, 2008). This evening’s program is dedicated to John and Carolyn Rader. The Sprocket Society …seeks to cultivate the love of the mechanical cinema, its arts and sciences, and to encourage film preservation by bringing film and its history to the public through screenings, educational activities, and our own archival efforts. www.sprocketsociety.org [email protected] The Northwest Film Forum Executive Director: Michael Seirwrath Managing Director: Susie Purves Programming Director: Adam Sekuler Associate Program Director: Peter Lucas Technical Director: Nora Weideman Assistant Technical Director: Matthew Cunningham Communications Director: Ryan Davis www.nwfilmforum.org nwfilmforum.wordpress.com THE STAR FILMS STUDIO, MONTREUIL, FRANCE The exterior of the glass-house studio Méliès built in his garden at Montreuil, France — the first movie The interior of the same studio. Méliès can be seen studio of its kind in the world. The short extension working at left (with the long stick). As you can with the sloping roof visible at far right is where the see, the studio was actually quite small.