CRANIAL NERVES: Functional Anatomy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pathophysiological Mechanisms and Functional Hearing Consequences of Auditory Neuropathy

doi:10.1093/brain/awv270 BRAIN 2015: 138; 3141–3158 | 3141 REVIEW ARTICLE Pathophysiological mechanisms and functional hearing consequences of auditory neuropathy Gary Rance1 and Arnold Starr2 The effects of inner ear abnormality on audibility have been explored since the early 20th century when sound detection measures were first used to define and quantify ‘hearing loss’. The development in the 1970s of objective measures of cochlear hair cell Downloaded from function (cochlear microphonics, otoacoustic emissions, summating potentials) and auditory nerve/brainstem activity (auditory brainstem responses) have made it possible to distinguish both synaptic and auditory nerve disorders from sensory receptor loss. This distinction is critically important when considering aetiology and management. In this review we address the clinical and pathophysiological features of auditory neuropathy that distinguish site(s) of dysfunction. We describe the diagnostic criteria for: (i) presynaptic disorders affecting inner hair cells and ribbon synapses; (ii) postsynaptic disorders affecting unmyelinated auditory http://brain.oxfordjournals.org/ nerve dendrites; (iii) postsynaptic disorders affecting auditory ganglion cells and their myelinated axons and dendrites; and (iv) central neural pathway disorders affecting the auditory brainstem. We review data and principles to identify treatment options for affected patients and explore their benefits as a function of site of lesion. 1 Department of Audiology and Speech Pathology, The University of Melbourne, -

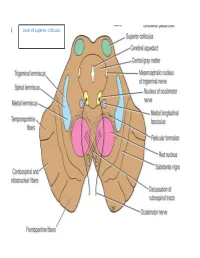

Level of Superior Colliculus ° Edinger- Westphal Nucleus ° Pretectal Nucleus: Close to the Lateral Part of the Superior Colliculus

Level of superior colliculus ° Edinger- Westphal nucleus ° pretectal nucleus: close to the lateral part of the superior colliculus. Red nucleus • Rounded mass of gray matter • Situated bt cerebral aqueduct and substantia nigra • Reddish blue(vascularity & iron containing pigment) • Afferents from: cerebral cortex,cerebellum,substa ntia nigra, thalamic nuclei, spinal cord • Efferent to: spinal cord, reticular formation. thalamus and substantia nigra • involved in motor coordination. Crus cerebri • Corticospinal & corticonuclear fibers (middle) • Frontopontine fibers (medial) • Temporopontine fibers (lateral) these descending tracts connect the cerebral cortex with spinal cord, cranial nerves nuclei, pons & cerebellum Level at superior colliculus ° Superior colliculus ° Occulomotor nucleus (posterior to MLF) ° Occulomotor n emerges through red nucleus ° Edinger-Westphal nucleus ° pretectal nucleus: close to the lateral part of the superior colliculus. ° MLF ° Medial , trigeminal, spinal leminiscus ( no lateral leminiscus) ° Red nucleus ° Substantia nigra ° Crus cerebri ° RF Substantia nigra ° Large motor nucleus ° is a brain structure located in the midbrain ° plays an important role in reward, addiction, and movement. ° Substantia nigra is Latin for "black substance" due to high levels of melanin ° has connections with basal ganglia ,cerebral cortex ° Concerned with muscle tone ° Parkinson's disease is caused by the death of neurons in the substantia nigra Oculomotor Nerve (III) • Main oculomotor nucleus • Accessory parasympathetic nucleus -

Nerves of the Orbit Optic Nerve the Optic Nerve Enters the Orbit from the Middle Cranial Fossa by Passing Through the Optic Canal

human anatomy 2016 lecture fourteen Dr meethak ali ahmed neurosurgeon Nerves of the Orbit Optic Nerve The optic nerve enters the orbit from the middle cranial fossa by passing through the optic canal . It is accompanied by the ophthalmic artery, which lies on its lower lateral side. The nerve is surrounded by sheath of pia mater, arachnoid mater, and dura mater. It runs forward and laterally within the cone of the recti muscles and pierces the sclera at a point medial to the posterior pole of the eyeball. Here, the meninges fuse with the sclera so that the subarachnoid space with its contained cerebrospinal fluid extends forward from the middle cranial fossa, around the optic nerve, and through the optic canal, as far as the eyeball. A rise in pressure of the cerebrospinal fluid within the cranial cavity therefore is transmitted to theback of the eyeball. Lacrimal Nerve The lacrimal nerve arises from the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve. It enters the orbit through the upper part of the superior orbital fissure and passes forward along the upper border of the lateral rectus muscle . It is joined by a branch of the zygomaticotemporal nerve, whi(parasympathetic secretomotor fibers). The lacrimal nerve ends by supplying the skin of the lateral part of the upper lid. Frontal Nerve The frontal nerve arises from the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve. It enters the orbit through the upper part of the superior orbital fissure and passes forward on the upper surface of the levator palpebrae superioris beneath the roof of the orbit . -

Cranial Nerve Palsy

Cranial Nerve Palsy What is a cranial nerve? Cranial nerves are nerves that lead directly from the brain to parts of our head, face, and trunk. There are 12 pairs of cranial nerves and some are involved in special senses (sight, smell, hearing, taste, feeling) while others control muscles and glands. Which cranial nerves pertain to the eyes? The second cranial nerve is called the optic nerve. It sends visual information from the eye to the brain. The third cranial nerve is called the oculomotor nerve. It is involved with eye movement, eyelid movement, and the function of the pupil and lens inside the eye. The fourth cranial nerve is called the trochlear nerve and the sixth cranial nerve is called the abducens nerve. They each innervate an eye muscle involved in eye movement. The fifth cranial nerve is called the trigeminal nerve. It provides facial touch sensation (including sensation on the eye). What is a cranial nerve palsy? A palsy is a lack of function of a nerve. A cranial nerve palsy may cause a complete or partial weakness or paralysis of the areas served by the affected nerve. In the case of a cranial nerve that has multiple functions (such as the oculomotor nerve), it is possible for a palsy to affect all of the various functions or only some of the functions of that nerve. What are some causes of a cranial nerve palsy? A cranial nerve palsy can occur due to a variety of causes. It can be congenital (present at birth), traumatic, or due to blood vessel disease (hypertension, diabetes, strokes, aneurysms, etc). -

Maxillary Nerve-Mediated Postseptoplasty Nasal Allodynia: a Case Report

E CASE REPORT Maxillary Nerve-Mediated Postseptoplasty Nasal Allodynia: A Case Report Shikha Sharma, MD, PhD,* Wilson Ly, MD, PharmD,* and Xiaobing Yu, MD*† Endoscopic nasal septoplasty is a commonly performed otolaryngology procedure, not known to cause persistent postsurgical pain or hypersensitivity. Here, we discuss a unique case of persis- tent nasal pain that developed after a primary endoscopic septoplasty, which then progressed to marked mechanical and thermal allodynia following a revision septoplasty. Pain symptoms were found to be mediated by the maxillary division of the trigeminal nerve and resolved after percuta- neous radiofrequency ablation (RFA) of bilateral maxillary nerves. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of maxillary nerve–mediated nasal allodynia after septoplasty. (A&A Practice. 2020;14:e01356.) GLOSSARY CT = computed tomography; FR = foramen rotundum; HIPAA = Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act; ION = infraorbital nerve; LPP = lateral pterygoid plate; MRI = magnetic reso- nance imaging; RFA = radiofrequency ablation; SPG = sphenopalatine ganglion; US = ultrasound ndoscopic nasal septoplasty is a common otolaryn- septoplasty for chronic nasal obstruction with resection of gology procedure with rare incidence of postsurgical the cartilage inferiorly and posteriorly in 2010. Before this Ecomplications. Minor complications include epistaxis, surgery, the patient only occasionally experienced mild septal hematoma, septal perforation, cerebrospinal fluid leak, headaches. However, his postoperative course was compli- and persistent obstruction.1 Numbness or hypoesthesia of the cated by significant pain requiring high-dose opioids. After anterior palate, secondary to injury to the nasopalatine nerve, discharge, patient continued to have persistent deep, “ach- has been reported, but is usually rare and temporary, resolv- ing” nasal pain which radiated toward bilateral forehead ing over weeks to months.2 Acute postoperative pain is also and incisors. -

Exä|Xã Tüà|Väx the Accessory Nerve Rezigalla AA*, EL Ghazaly A*, Ibrahim AA*, Hag Elltayeb MK*

exä|xã TÜà|vÄx The Accessory Nerve Rezigalla AA*, EL Ghazaly A*, Ibrahim AA*, Hag Elltayeb MK* The radical neck dissection (RND) in the management of head and neck cancers may be done in the expense of the spinal accessory nerve (SAN) 1. De-innervations of the muscles supplied by SAN and integrated in the movements of the shoulder joint, often result in shoulder dysfunction. Usually the result is shoulder syndrome which subsequently affects the quality of life1. The modified radical neck dissections (MRND) and selective neck dissection (SND) intend to minimize the dysfunction of the shoulder by preserving the SAN, especially in supra-hyoid neck dissection (Level I-III±IV) and lateral neck dissection (level II-IV)2, 3. This article aims to focus on the SAN to increase the awareness during MRND and SND. Keywords: Spinal accessory, Sternocleidomastoid, Trapezius, Cervical plexus. he accessory nerve is a motor nerve The Cranial Root: but it is considered as containing some The cranial root is the smaller, attached to the sensory fibres. It is formed in the post-olivary sulcus of the medulla oblongata T 8,10 posterior cranial fossa by the union of its (Fig.1) and arises forms the caudal pole of 4, 7, 9 cranial and spinal roots 4-8 (i.e. the internal the nucleus ambiguus (SVE) and possibly 11, 14 and external branches respectively9,10) but also of the dorsal vagal nucleus , although 11 these pass for a short distance only11. The both of them are connected . cranial root joins the vagus nerve and The nucleus ambiguus is the column of large considered as a part of the vagus nerve, being motor neurons that is deeply isolated in the branchial or special visceral efferent reticular formation of the medulla 11 nerve4,5,9,11. -

Circuits in the Rodent Brainstem That Control Whisking in Concert with Other Orofacial Motor Actions

Neuroscience 368 (2018) 152–170 CIRCUITS IN THE RODENT BRAINSTEM THAT CONTROL WHISKING IN CONCERT WITH OTHER OROFACIAL MOTOR ACTIONS y y LAUREN E. MCELVAIN, a BETH FRIEDMAN, a provides the reset to the relevant premotor oscillators. HARVEY J. KARTEN, b KAREL SVOBODA, c FAN WANG, d Third, direct feedback from somatosensory trigeminal e a,f,g MARTIN DESCHEˆ NES AND DAVID KLEINFELD * nuclei can rapidly alter motion of the sensors. This feed- a Department of Physics, University of California at San Diego, back is disynaptic and can be tuned by high-level inputs. La Jolla, CA 92093, USA A holistic model for the coordination of orofacial motor actions into behaviors will encompass feedback pathways b Department of Neurosciences, University of California at San Diego School of Medicine, La Jolla, CA 92093, USA through the midbrain and forebrain, as well as hindbrain c areas. Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Janelia Research This article is part of a Special Issue entitled: Barrel Campus, Ashburn, VA 20147, USA Cortex. Ó 2017 IBRO. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights d Department of Neurobiology, Duke University Medical reserved. Center, Durham, NC 27710, USA e Department of Psychiatry and Neuroscience, Laval University, Que´bec City, G1J 2G3, Canada f Key words: coupled oscillators, facial nucleus, hypoglossal Section of Neurobiology, University of California at San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093, USA nucleus, licking, orienting, tongue, vibrissa. g Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of California at San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093, USA Contents Introduction 153 Abstract—The world view of rodents is largely determined Coordination of multiple orofacial motor actions 153 by sensation on two length scales. -

Anatomy of Maxillary and Mandibular Local Anesthesia

Anatomy of Mandibular and Maxillary Local Anesthesia Patricia L. Blanton, Ph.D., D.D.S. Professor Emeritus, Department of Anatomy, Baylor College of Dentistry – TAMUS and Private Practice in Periodontics Dallas, Texas Anatomy of Mandibular and Maxillary Local Anesthesia I. Introduction A. The anatomical basis of local anesthesia 1. Infiltration anesthesia 2. Block or trunk anesthesia II. Review of the Trigeminal Nerve (Cranial n. V) – the major sensory nerve of the head A. Ophthalmic Division 1. Course a. Superior orbital fissure – root of orbit – supraorbital foramen 2. Branches – sensory B. Maxillary Division 1. Course a. Foramen rotundum – pterygopalatine fossa – inferior orbital fissure – floor of orbit – infraorbital 2. Branches - sensory a. Zygomatic nerve b. Pterygopalatine nerves [nasal (nasopalatine), orbital, palatal (greater and lesser palatine), pharyngeal] c. Posterior superior alveolar nerves d. Infraorbital nerve (middle superior alveolar nerve, anterior superior nerve) C. Mandibular Division 1. Course a. Foramen ovale – infratemporal fossa – mandibular foramen, Canal -> mental foramen 2. Branches a. Sensory (1) Long buccal nerve (2) Lingual nerve (3) Inferior alveolar nerve -> mental nerve (4) Auriculotemporal nerve b. Motor (1) Pterygoid nerves (2) Temporal nerves (3) Masseteric nerves (4) Nerve to tensor tympani (5) Nerve to tensor veli palatine (6) Nerve to mylohyoid (7) Nerve to anterior belly of digastric c. Both motor and sensory (1) Mylohyoid nerve III. Usual Routes of innervation A. Maxilla 1. Teeth a. Molars – Posterior superior alveolar nerve b. Premolars – Middle superior alveolar nerve c. Incisors and cuspids – Anterior superior alveolar nerve 2. Gingiva a. Facial/buccal – Superior alveolar nerves b. Palatal – Anterior – Nasopalatine nerve; Posterior – Greater palatine nerves B. -

Studies of Oculomotor-System Neural Connections Ronald S

Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science Volume 34 Article 26 1980 How We Look: Studies of Oculomotor-System Neural Connections Ronald S. Remmel University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Robert D. Skinner University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas Part of the Sense Organs Commons Recommended Citation Remmel, Ronald S. and Skinner, Robert D. (1980) "How We Look: Studies of Oculomotor-System Neural Connections," Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science: Vol. 34 , Article 26. Available at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas/vol34/iss1/26 This article is available for use under the Creative Commons license: Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-ND 4.0). Users are able to read, download, copy, print, distribute, search, link to the full texts of these articles, or use them for any other lawful purpose, without asking prior permission from the publisher or the author. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science, Vol. 34 [1980], Art. 26 HOW WE LOOK: STUDIES OF OCULOMOTOR-SYSTEM NEURAL CONNECTIONS . R. S. REMMELandR. D. SKINNER i Department of Physiology and Biophysics and Department of Anatomy University of Arkansas forMedical Sciences Little Rock, Arkansas 72205 ABSTRACT The neural connections of the reticular formation (RF) withthe vestibular nuclei (8V)and the ascending medial longitudinal fasciculus (MLF) were studied, because many neurons in these structures carry eye-movement and head-movement (vestibular) signals and are only one or two synaptic connections removed from eye motorneurons. -

DR. Sanaa Alshaarawy

By DR. Sanaa Alshaarawy 1 By the end of the lecture, students will be able to : Distinguish the internal structure of the components of the brain stem in different levels and the specific criteria of each level. 1. Medulla oblongata (closed, mid and open medulla) 2. Pons (caudal, mid “Trigeminal level” and rostral). 3. Mid brain ( superior and inferior colliculi). Describe the Reticular formation (structure, function and pathway) being an important content of the brain stem. 2 1. Traversed by the Central Canal. Motor Decussation*. Spinal Nucleus of Trigeminal (Trigeminal sensory nucleus)* : ➢ It is a larger sensory T.S of Caudal part of M.O. nucleus. ➢ It is the brain stem continuation of the Substantia Gelatinosa of spinal cord 3 The Nucleus Extends : Through the whole length of the brain stem and upper segments of spinal cord. It lies in all levels of M.O, medial to the spinal tract of the trigeminal. It receives pain and temperature from face, forehead. Its tract present in all levels of M.O. is formed of descending fibers that terminate in the trigeminal nucleus. 4 It is Motor Decussation. Formed by pyramidal fibers, (75-90%) cross to the opposite side They descend in the Decuss- = crossing lateral white column of the spinal cord as the lateral corticospinal tract. The uncrossed fibers form the ventral corticospinal tract. 5 Traversed by Central Canal. Larger size Gracile & Cuneate nuclei, concerned with proprioceptive deep sensations of the body. Axons of Gracile & Cuneate nuclei form the internal arcuate fibers; decussating forming Sensory Decussation. Pyramids are prominent ventrally. 6 Formed by the crossed internal arcuate fibers Medial Leminiscus: Composed of the ascending internal arcuate fibers after their crossing. -

Morfofunctional Structure of the Skull

N.L. Svintsytska V.H. Hryn Morfofunctional structure of the skull Study guide Poltava 2016 Ministry of Public Health of Ukraine Public Institution «Central Methodological Office for Higher Medical Education of MPH of Ukraine» Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Ukranian Medical Stomatological Academy» N.L. Svintsytska, V.H. Hryn Morfofunctional structure of the skull Study guide Poltava 2016 2 LBC 28.706 UDC 611.714/716 S 24 «Recommended by the Ministry of Health of Ukraine as textbook for English- speaking students of higher educational institutions of the MPH of Ukraine» (minutes of the meeting of the Commission for the organization of training and methodical literature for the persons enrolled in higher medical (pharmaceutical) educational establishments of postgraduate education MPH of Ukraine, from 02.06.2016 №2). Letter of the MPH of Ukraine of 11.07.2016 № 08.01-30/17321 Composed by: N.L. Svintsytska, Associate Professor at the Department of Human Anatomy of Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Ukrainian Medical Stomatological Academy», PhD in Medicine, Associate Professor V.H. Hryn, Associate Professor at the Department of Human Anatomy of Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Ukrainian Medical Stomatological Academy», PhD in Medicine, Associate Professor This textbook is intended for undergraduate, postgraduate students and continuing education of health care professionals in a variety of clinical disciplines (medicine, pediatrics, dentistry) as it includes the basic concepts of human anatomy of the skull in adults and newborns. Rewiewed by: O.M. Slobodian, Head of the Department of Anatomy, Topographic Anatomy and Operative Surgery of Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Bukovinian State Medical University», Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor M.V. -

The Mandibular Nerve - Vc Or VIII by Prof

The Mandibular Nerve - Vc or VIII by Prof. Dr. Imran Qureshi The Mandibular nerve is the third and largest division of the trigeminal nerve. It is a mixed nerve. Its sensory root emerges from the posterior region of the semilunar ganglion and is joined by the motor root of the trigeminal nerve. These two nerve bundles leave the cranial cavity through the foramen ovale and unite immediately to form the trunk of the mixed mandibular nerve that passes into the infratemporal fossa. Here, it runs anterior to the middle meningeal artery and is sandwiched between the superior head of the lateral pterygoid and tensor veli palatini muscles. After a short course during which a meningeal branch to the dura mater, and the nerve to part of the medial pterygoid muscle (and the tensor tympani and tensor veli palatini muscles) are given off, the mandibular trunk divides into a smaller anterior and a larger posterior division. The anterior division receives most of the fibres from the motor root and distributes them to the other muscles of mastication i.e. the lateral pterygoid, medial pterygoid, temporalis and masseter muscles. The nerve to masseter and two deep temporal nerves (anterior and posterior) pass laterally above the medial pterygoid. The nerve to the masseter continues outward through the mandibular notch, while the deep temporal nerves turn upward deep to temporalis for its supply. The sensory fibres that it receives are distributed as the buccal nerve. The 1 | P a g e buccal nerve passes between the medial and lateral pterygoids and passes downward and forward to emerge from under cover of the masseter with the buccal artery.