Navigating Terra Nullius: the Ababda and the Case for Indigenous Land Rights in Bir Tawil

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regime Crises, Political Exclusion and Indiscriminate Violence in Africa

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: RISKING WAR: REGIME CRISES, POLITICAL EXCLUSION AND INDISCRIMINATE VIOLENCE IN AFRICA Philip Gregory Roessler, Doctor of Philosophy, 2007 Directed By: Professor Mark I. Lichbach Department of Government and Politics Between 1956 and 1999 one-third of the civil wars in the world occurred in sub- Saharan Africa. The prevailing explanation given to account for this fact is the economic weakness of African states. While low income is a robust determinant of civil war onset in global models, it is not as precise a predictor within sub-Saharan Africa. Instead, I argue that civil war is often a consequence of how African rulers respond to threats to regime survival, such as failed coups d’etat and other regime crises. In the wake of regime crises, rulers, concerned by their tenuous hold on power, seek to reduce the risk of future coups by eliminating disloyal agents from within the government and increasing spoils for more trusted clients to try to guarantee their support should another coup or threat materialize. The problem for the ruler is distinguishing loyal agents from traitors. To overcome this information problem rulers often use ethnicity as a cue to restructure their ruling networks, excluding perceived ‘ethnic enemies’ from spoils. The consequence of such ethnic exclusion is that, due to the weakness of formal state structures, the ruler forfeits his leverage over and information about such societal groups, undermining the government’s ability to effectively prevent and contain violent mobilization and increasing the risk of civil war. To test this hypothesis, I employ a nested research design. -

ACLED) - Revised 2Nd Edition Compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018

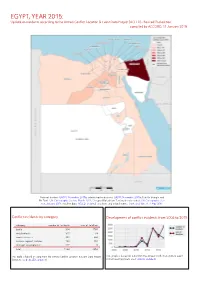

EGYPT, YEAR 2015: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) - Revised 2nd edition compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018 National borders: GADM, November 2015b; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015a; Hala’ib triangle and Bir Tawil: UN Cartographic Section, March 2012; Occupied Palestinian Territory border status: UN Cartographic Sec- tion, January 2004; incident data: ACLED, undated; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 Conflict incidents by category Development of conflict incidents from 2006 to 2015 category number of incidents sum of fatalities battle 314 1765 riots/protests 311 33 remote violence 309 644 violence against civilians 193 404 strategic developments 117 8 total 1244 2854 This table is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project This graph is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event (datasets used: ACLED, undated). Data Project (datasets used: ACLED, undated). EGYPT, YEAR 2015: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) - REVISED 2ND EDITION COMPILED BY ACCORD, 11 JANUARY 2018 LOCALIZATION OF CONFLICT INCIDENTS Note: The following list is an overview of the incident data included in the ACLED dataset. More details are available in the actual dataset (date, location data, event type, involved actors, information sources, etc.). In the following list, the names of event locations are taken from ACLED, while the administrative region names are taken from GADM data which serves as the basis for the map above. In Ad Daqahliyah, 18 incidents killing 4 people were reported. The following locations were affected: Al Mansurah, Bani Ebeid, Gamasa, Kom el Nour, Mit Salsil, Sursuq, Talkha. -

Ifbb Elite Professional Qualifier 2021 Ifbb World

IFBB ELITE PROFESSIONAL QUALIFIER 2021 IFBB WORLD RANKING EVENT WELCOME Dear Brothers, Friends & Colleagues, The Egyptian Federation of Bodybuilding & Fitness (E.F.B.F) is proudly inviting all athletes from IFBB-affiliated National Federations from Europe, Africa and Asia to participate in the Muscle Tech Egypt IFBB Diamond Cup that will be held in the wonderful city of Cairo, Egypt during the period from the 18th till the 20th of February, 2021. Special Thanks to Dr. Rafael Santonja, the President of the International Federation of Bodybuilding and Fitness (IFBB) for his continuous support for our beloved sport and his special care of these championships. We are all proud of our great leader whom we learned from him a lot, and experienced from his great talented character. I would also like to convey my sincere thanks & gratitude to Mr. Abdelazeem Hegazy, the Chairman of the Muscletech Egypt for sponsoring such an important sports event, confirming his vision to support bodybuilding sport as a healthy lifestyle. The event will include Junior Men’s Bodybuilding, Men’s Bodybuilding, Men’s Classic Physique, Men’s Physique & Masters Men’s Bodybuilding. Once again welcome to the marvelous Cairo; one of the most attractive cities all over the world; and I hope that your stay in our country will be a memory of joy and pleasure. Dr. Eng. Adel Fahim Executive Assistant & Vice-President, IFBB President Egyptian, Arab & African Federations ABOUT EGYPT: Egypt, country located in the northeastern corner of Africa. Egypt’s heartland, the Nile River valley and delta, was the home of one of the principal civilizations of the ancient Middle East and, like Mesopotamia farther east, was the site of one of the world’s earliest urban and literate societies. -

The Internationalists

FIFTEEN WHY IS THERE STILL SO MUCH CONFLICT? The decision to outlaw war changed the world. Wars between states are now rare. Conquest has become the exception, not the rule. But if this is true, why have so many missed the remarkable success of the outlawry of war? At least part of the reason is that the postwar world has been far from peaceful. India and Pakistan have fought over the region of Kashmir off and on since 1947. Since 1948, conflict involving Israel has led to three interstate wars and several intifadas. War raged in Korea from 1950 to 1953 and in Vietnam from 1955 to 1975. Genocidal conflicts erupted in Yugoslavia (now the former Yugoslavia) and Rwanda in the 1990s, and civil war ravaged Sudan for more than two decades. In 2014, the United States and China began playing a high-stakes game of chicken over islands in the South China Sea and many fear a war with China in the near future. And in 2015 alone, high-fatality civil wars continued in Nigeria, South Sudan, Yemen, Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Somalia, and Ukraine.1 Why, if war has been outlawed, is there still so much conflict? The answer is that these conflicts are not prohibited by the Pact. Indeed, they are the predictable consequences of it. Even though the Peace Pact was extraordinarily—many thought foolishly—ambitious, it was nonetheless limited in its scope. It outlawed territorial aggression by one state against another. The United Nations Charter followed its example, prohibiting “the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state.” This prohibition has been remarkably effective, as the decline in conquest and interstate war shows. -

Boundary News

Boundary news Boundary news Headlines Press conference to address the Hala’ib Triangle land dispute between Sudan and Egypt (14 January 2016) The foreign ministers of Sudan and Egypt held a joint press conference on the 9th of January to address the countries’ longstanding dispute over the territory that straddles their shared border: the Hala’ib Triangle. In 1899, the AngloEgyptian condominium agreement for Sudan set the boundary on the 22nd parallel as the border between the two countries. Three years later in 1902 the British created a new dividing line, granting administration of the area to Sudan because of its proximity and access to Khartoum. The administrative boundary created the Hala'ib triangle north of the 22nd parallel and a small area, the Bir Tawil south of the parallel. With the independence of Sudan in 1956 both countries claimed sovereignty over the Hala’ib triangle; Egypt regarded the 22nd parallel as the territorial boundary between the two countries whilst Sudan claimed the 1902 administrative border. Conflict erupted two years later, in 1958, when Sudan announced plans to hold elections in the Hala’ib triangle. Egypt’s President Nasser sent troops into the disputed region but withdrew a month later. Joint control of the land remained in effect until 1992, when Egypt protested Sudan’s granting of exploration rights for the waters off the triangle to a Canadian oil company. In 2014, Cairo signed contracts with companies for gold exploration in the area. Khartoum responded by deploying a force of marines. In the press conference, Sudanese Minister of Foreign Affairs Ibrahim Ghandour announced that Sudan is renewing its complaint against Egypt in the UN Security Council in a bid to save its historical rights to the area. -

Report from Practically Somewhere: Liberland, Sovereignty, and Norm Contestation

REPORT FROM PRACTICALLY SOMEWHERE: LIBERLAND, SOVEREIGNTY, AND NORM CONTESTATION By Sam Koebrich Submitted to Central European University Department of International Relations In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Supervisor: Professor Alexander Astrov Word Count: 16,671 Budapest, Hungary 2017 CEU eTD Collection Abstract: Liberland is a state that does not exist––or rather, it is not recognized by any other state and is occupied by Croatian police despite Croatia not claiming the territory. This project to form a new sovereign state on what would otherwise be terra nullius reignites debates of the normative and legal rule of sovereignty in its declaratory and constitutive forms. The exclusion of Liberland from international society demonstrates the operative paradigm of sovereignty as favoring norm over law. By examining why this is so, the purpose of sovereignty as a structure to reproduce power asymmetries in international society is revealed. Acknowledgments: I would like to thank my supervisor, Alexander Astrov for entertaining a thesis topic many would scoff at. I paid little attention to sovereignty or norms at the beginning of this degree, but through his course instruction, syllabus, and comments these are now concepts I care quite a bit about. I would like to thank my parents for their emotional (and sometimes financial) support in getting myself and a wheelchair onto a plane to Budapest. I would like to thank my friends in Canada for trying to push me further to the left, and my friends in the US for keeping me grounded. Lastly, I would like to thank the Liberlandians I met for accepting me into their community despite my drastically different worldview. -

LXVII Sixty-Seventh Session Security Council

LXVII sixty-seventh session Security Council !!! Berkeley Model United Nations Welcome Letter Hi! My name is Soham Kale, and I’ll be your head chair for BMUN LXVII Security Council. I’m a junior here at UC Berkeley studying Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, as well as Engineering Physics. I’m originally from South Florida, but the last two years I’ve spent in the Bay Area have been some of the best of my life. I’ve been doing MUN for 7 years now, and it’s honestly been one of the most rewarding experiences I’ve ever been in. It’s given me a chance to broaden my knowledge past my STEM field, and I’ve met some of the most passionate, intelligent, and overall amazing individuals during my time as both a delegate and a chair. Outside of MUN, I really love to code, sketch my surroundings, swim, and buys things I don’t need from Amazon. To me, Security Council provides the unique potential to tackle specific, influential issues, and set far-reaching precedence as you go. One thing I’ve loved about this committee is that you really can’t make any blanket statements; every single clause has to be definite in its scope and explicit in its terminology. It only takes a dash of imagination to see the resolutions and debate in SC being replicated in the real UN, with lasting impacts that are both incredible to see transpire yet realistic in their scope. I hope that the work that gets done this March follows suit, and we expect delegates to bring only the best they have to offer, in order to get out of it the most they can. -

Where There's a Will, There's A

Where There’s a Will, There’s a Way Ten Ways of Settling an Insoluble Territorial dispute Igor Yu. Okunev Abstract Understanding ‘sovereignty’ as one and indivisible substance is very convenient for politicians and lawyers, but in the modern political reality it is hardly achievable. Alternative approaches to sovereignty, which imply the possibility of blending the legal systems of different states in the same territory, considerably expand opportunities for resolving territorial disputes. In this article vast historical material is used to illustrate the experience of implementing various models of territorial governance, such as an associated state, transboundary region, sovereign region, leased territory, free territory, no-man’s territory, buffer zone, temporary administration, condominium, and commune. The described set of options may help break the deadlock in negotiations on almost any territorial dispute, provided the parties concerned have the political will to achieve a peaceful compromise. Igor Yu. Okunev, Ph.D. (Political Science) Department of Comparative Political Science, MGIMO University, Moscow, Russia Associate Professor; Center for European Studies, MGIMO University, Moscow, Russia Senior Research Fellow ORCID: 0000-0003-3292-9829 RSCI Author ID: 565228 SPIN RSCI: 7633-0618 Scopus Author ID: 56433053800 Researcher ID: E-4038-2012 Tel: +7 945 433 3495, ext. 1501 Address: 76, Vernadsky Prospect, Moscow 119454, Russia DOI: 10.31278/1810-6374-2019-17-3-152-174 152 RuSSIa IN GLOBal AFFAIRS Where There’s a Will, There’s a Way Keywords: territorial disputes, associated state, transboundary region, sovereign region, leased territory, free territory, no-man’s territory, buffer zone, condominium erritorial disputes are extremely difficult to resolve. -

Durham Research Online

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Durham Research Online Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 19 June 2018 Version of attached le: Accepted Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Leshem, Noam and Pinkerton, Alasdair (2018) 'Rethinking expeditions : on critical expeditionary practice.', Progress in Human Geography . Further information on publisher's website: https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132518768413 Publisher's copyright statement: Noam Leshem and Alasdair Pinkerton, Rethinking expeditions: On critical expeditionary practice, Progress in Human Geography (rst published online: April 18, 2018). Copyright c 2018 The Author(s). Reprinted by permission of SAGE Publications. Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 http://dro.dur.ac.uk Rethinking Expeditions On Critical Expeditionary Practice Noam Leshem, Durham University Alasdair Pinkerton, Royal Holloway University of London I. Introduction For two months in 2015, we undertook an expedition “Into No-Man’s Land” (Leshem and Pinkerton 2015). -

Master's Thesis Regional Studies Development Geography

TypeUnitOrDepartmentHere TypeYourNameHere Master’s Thesis Regional Studies Development Geography REFLECTIONS ON NATIONAL GEOPOLITICS –HOW NATIONAL GEOPOLITICS ARE MIRRORED IN WEB MAP SERVICES Elina Andersson 2013 Supervisors: Ph.D. Mika Siljander Professor John Westerholm UNIVERSITY OF HELSINKI DEPARTMENT OF GEOSCIENCES AND GEOGRAPHY DIVISION OF GEOGRAPHY PL 64 (Gustaf Hällströmin katu 2) 00014 University of Helsinki 1 1. Introduction…………………………………………………....…. 8 2. Cartography and geopolitics………………………………....…..11 2.1. What is cartography and what is a map………..………….....…….11 2.2. Maps on the Web…………………………………………..….…13 2.1.1. Web map services………………………………….....……15 2.2. Can the map ever be true? ……………………………….….…16 2.3. The design of maps…………………………………………….…....17 2.3.1. Projection and scale…………………………..…….......18 2.3.2. Areas, lines and symbols..………………………....…...19 2.3.3. Coloring………...………………… ……………..….…20 2.3.4. Toponymy……………………………………….…..….21 2.4. The geopolitical map………………………………………........23 2.5. Contemporary geopolitics………………………………...…….25 2.6. The unsettled Heart of the Middle East………………….…......26 2.7. Brief highlights on the foreign affairs of Israel, the USA and Russia………………………………………………………………...28 2.8. Challenges, validity and reliability of the research……………...29 3. Study area and research materials………………………...……...31 3.1. Study area: “The Heart of the Middle East” ………….…….....31 3.2. ABmaps: The service of a modern LBS-company.………….…....32 3.3. Google Maps: An obvious world giant…………………..…….…..33 3.4. Yandex Maps: A rapidly growing rival…………………………....34 2 4. Research methods. …………………………………………..….….35 4.1. Structured content analysis………………………………..........….35 4.2. From entireties to components, and back to entireties.………..…36 5. Results………………………..………………..…………..……..…38 5.1. Structured content analysis 1: Map tools and design....…….…....38 5.1.1. -

Republic of the Sudan ﺟﻣﮫورﻳﺔ اﻟﺳودان Jumhūriyyat As-Sūdān (Arabic)

Coor din ates: 1 5 °N 03 2 °E Sudan T he Sudan or Sudan (US: /suˈdæn/ ( listen), UK: /suˈdɑːn [9][10] Republic of the Sudan as-Sūdān), also known as اﻟﺴﻮدان :dæn/; Arabicˈ- , ﺟﻣﮫورﻳﺔ اﻟﺳودان North Sudan since South Sudan's independence and (Jumhūriyyat as-Sūdān (Arabic ﺟﻤﮭﻮرﯾﺔ :officially the Republic of the Sudan[11] (Arabic Jumhūriyyat as-Sūdān), is a country in Northeast اﻟﺴﻮدان Africa. It is bordered by Egypt to the north, the Red Sea, Eritrea and Ethiopia to the east, South Sudan to the south, the Central African Republic to the southwest, Chad to the west and Libya to the northwest. It houses 37 million Flag [12] people (2017 ) and occupies a total area of 1.861.484 Emblem square kilometres (7 18.7 22 square miles), making it the (Arabic) اﻟﻧﺻر ﻟﻧﺎ :Motto third largest country in Africa.[13] Sudan's predominant "An-Naṣr lanā" [14] religion is Islam, and its official languages are Arabic and "Victory is ours" English. The capital is Khartoum, located at the confluence Anthem: of the Blue and White Nile. ﻧﺣن ﺟﻧد ﷲ، ﺟﻧد اﻟوطن Naḥnu Jund Allah, Jund Al- The history of Sudan goes back to the Pharaonic period, waṭan (transliteration) witnessing the kingdom of Kerma (c. 2500 BC-1500 BC), the We are the Soldiers of God, the Soldiers of the subsequent rule of the Egyptian New Kingdom (c. 1500 BC- Nation 107 0 BC) and the rise of the kingdom of Kush (c. 7 85 BC- 0:00 MENU 350 AD), which would in turn control Egypt itself for nearly a century. -

SUDAN, FIRST QUARTER 2020: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020

SUDAN, FIRST QUARTER 2020: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015a; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015b; Abyei Area: SS- NBS, 1 December 2008; South Sudan/Sudan border status, Hala’ib triangle and Bir Tawil: UN Cartographic Sec- tion, March 2012; incident data: ACLED, 20 June 2020; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 SUDAN, FIRST QUARTER 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Protests 117 0 0 Conflict incidents by category 2 Violence against civilians 49 22 57 Development of conflict incidents from March 2018 to March 2020 2 Battles 18 12 42 Riots 18 0 0 Methodology 3 Strategic developments 10 0 0 Conflict incidents per province 4 Explosions / Remote 3 2 11 violence Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 215 36 110 Disclaimer 6 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). Development of conflict incidents from March 2018 to March 2020 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). 2 SUDAN, FIRST QUARTER 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Methodology this overview might therefore differ from the original ACLED data.