2020 Conservation Outlook Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mapaamazonia2012-Deforestationing

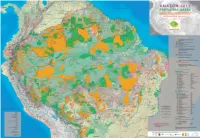

Amazon and human population Bolivia Brasil Colombia Ecuador Guyana Guyane Française Perú Suriname Venezuela total Amazon Protected Areas and Indigenous Territories % of the national % of the national % of the national % of the national % of the national % of the national % of the national % of the national % of the national % of the Amazon total total total total total total total total total total In Amazon the protection of socioenvironmental diversity is being consolidated through the recognition of the territorial rights of indigenous peoples A M A Z O N 2012 Total population and the constitution of a varied set of protected areas. These conservation strategies have been expanding over recent years and today cover a 8,274,325 - 191,480,630 - 42,090,502 - 14,483,499 - 751,000 - 208,171 - 28,220,764 - 492,829 - 27,150,095 - 313,151,815 (nº of inhabitants) surface area of 3,502,750 km2 – 2,144,412 km2 in Indigenous Territories and 1,696,529 km2 in Protected Natural Areas, with an overlap of 336,365 2 Amazon population km between them – which corresponds to 45% of the region. PROTECTED AREAS and INDIGENOUS TERRITORIES 1,233,727 14.9% 23,654,336 12.4% 1,210,549 2.9% 739,814 5.1% 751,000 100.0% 208,171 100.0% 3,675,292 13.0% 492,829 100.0% 1,716,984 6.3% 33,682,702 10.8% (nº of inhabitants) The challenge faced in terms of attaining the objectives of strengthening the cultural and biological diversity of Amazon, represented in indigenous Total area of the country (km2) 1,098,581 - 8,514,876 - 1,141,748 - 249,041 - 214,969 - 86,504 - 1,285,215 - 163,820 - 916,445 - 13,671,199 territories and protected areas, encompasses a variety of aspects. -

Executive Summary of the National Action Plan For

EXECUTIVEEXECUTIVE SUMMARYSUMMARY OFOF THETHE NATIONALNATIONAL ACTIONACTION PLANPLAN FORFOR THETHE CONSERVATIONCONSERVATION OFOF MURIQUISMURIQUIS The mega-diverse country of Brazil is responsible for managing the largest natural patrimony in the world. More than 120,000 species of animals oc- cur throughout the country. Among these species, 627 are registered on the Official List of Brazilian Fauna Threatened with Extinction. The most affected Biome is the Atlantic Forest, within which 50% of the Critically Endangered mammalian species are primates endemic to this biome. Carla de Borba Possamai The Chico Mendes Institute is responsible for the development of strat- egies for the conservation of species of Brazilian fauna, evaluation of the conservation status of Brazilian fauna, publication of endangered species lists and red books and the development, implementation and monitoring of National Action Plans for the conservation of endangered species. Action plans are management tools for conservation of biodiversity and aligning strategies with different institutional stakeholders for the recovery and conservation of endangered species. The Joint Ordinance No. 316 of Septem- ber 9, 2009, was established as the legal framework to implement strategies. It indicates that action plans together with national lists of threatened species and red books, constitute one of the instruments of implementation of the National Biodiversity Policy (Decree 4.339/02). TAXANOMIC CLASSIFICATION Phylum: Chordata - Class: Mammalia - Order: Primates Family: Atelidae Gray, 1825 - Subfamily: Atelinae Gray, 1825 Genus: Brachyteles Spix, 1823 Species: Brachyteles arachnoides (E. Geoffroy, 1806) Brachyteles hypoxanthus (Kuhl, 1820) POPULAR NAMES Popular names include: Muriqui, Mono Carvoeiro, Mono, Miriqui, Buriqui, Buriquim, Mariquina or Muriquina. In English, they are also known as Woolly Spider Monkeys. -

Conservation Units Under Risk Attacks Against Protected Areas Cover an Area Near the Size of Portugal

RICARDO FRANCO PARK (MT) © MARIO FRIEDLANDER COVER ANAREANEARTHESIZEOFPORTUGAL PROTECTEDAREAS AGAINST ATTACKS UNITS CONSERVATION OF THEOFFENSIVE VECTORS ARE THEMAIN AND MINING LAND GRABBING 2017 REPORT BRAZIL UNDER RISK over about 10% of the territory of federal conservation units, a conservative conservative a units, conservation federal of territory the of 10% about over looms threat The Planalto. do Palácio from support the with thrive, to room base and with strong lobby from ruralist and mining sectors Units promoted by members of Michel Temer’s government parliamentary have found Pressures to undo or reduce the size or protection status of Conservation Brazil is experiencing an unprecedented offensive against protected areas. by theConvention onBiologicalDiversity (CBD). made commitments the with compliance threatening and (ARPA) Program tion, as well as involving The dismantling of the Amazon Protected Areas Conven Climate Nations United the in emissions gas greenhouse reducing in more deforestation in the Amazon, damaging the Brazilian targets for de. As one side gains momentum, the impact on protected areas can result world leaderintheextensionofprotectedareasat endofthelastdeca National System of Conservation Units (SNUC), which put ning Brazil companies as or land the grabbers of public lands. On the other hand, the who occupy protected areas irregularly or would like to occupy them, mi The conflict of interest is not new. On one hand, there are rural producers almost thesizeofterritoryPortugal. the country and involves an area of about 80 thousand square kilometers, of South to North from goes areas protected the against Offensive estimate. - - - The potential for damage is enormous. Suffice to say that one of the projects under negotiation in the National Congress, PL 3751, renders all the acts of creation of conservation units whose private owners have not been indem- nified in the period of five years obsolete. -

Program Cerrado Pantanal

© Bento Viana / WWF-Brazil © Bento Viana FACTSHEET BR 2016 CERRADO Adriano Gambarini / WWF-Brazil © PANTANALPROGRAM © Adriano Gambarini / WWF-Brazil © / WWF-Brazil © Bento Viana THE WWF-BRAZIL WWF-Brazil is an environmental organization that works to conserve various Brazilian ecosystems, including two of South America’s most important regions: the Cerrado and the Pantanal. The Cerrado, Pantanal and Upper Paraguay River Basin are included in WWF’s 35 global priority places. This vast area is the focus of our conservation work undertaken through the Cerrado Pantanal Program. © Adriano Gambarini / WWF-Brazil © CERRADO PANTANAL PRIORITY AREAS The Cerrado Ecoregion The Pantanal Ecoregion Upper Paraguay River Basin © Bento Viana / WWF-Brazil © Bento Viana CERRADO © Bento Viana / WWF-Brazil © Bento Viana Stretching across 11 states and the Federal District, the Cerrado is South America’s second largest phytogeographic domain. It can also be found in the states of Roraima, Amapá, Amazonas and Pará and partially covers Bolivia and Paraguay. The Cerrado covers roughly 25% of the country and is one of the biologically richest savannas on the planet. The Cerrado is connected to four of Brazil’s five biomes – the Amazon, Caatinga, Atlantic Forest, and Pantanal. It is regarded as the “cradle” of Brazil’s water resources, since it feeds not only Brazil’s major aquifers, but also six of the country’s eight river basins and the Pantanal. Area Over 2 million sq km Conservation Less than 10% of the Cerrado is covered by protected areas Biodiversity The -

Hunting of Mammal Species in Protected Areas of the Southern Bahian Atlantic Forest, Brazil

Hunting of mammal species in protected areas of the southern Bahian Atlantic Forest, Brazil L UCIANA C. CASTILHO,KRISTEL M. DE V LEESCHOUWER,E.J.MILNER-GULLAND and A LEXANDRE S CHIAVETTI Abstract To investigate the practice of hunting by local peo- social and cultural traditions (Bennett & Robinson, ; ple in the southern Bahia region of Brazil and provide infor- Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, mation to support the implementation of the National Action ). However, wildlife harvest has reached unsustainable le- Plan for Conservation of the Central Atlantic Forest vels in many places because of the increasing human popu- Mammals, we conducted interviews with residents of lation and demand for wild meat (Peres, ; Bennett et al., three protected areas and a buffer zone. Thirty-seven percent ), improved hunting technologies and increased access of respondents stated that they had captured an animal op- to forests (Bennett et al., ;Fa&Brown,). Besides portunistically, % hunted actively and %didnothunt. causing species declines or extinctions (Cullen et al., ; The major motivation for hunting was consumption but peo- Corlett, ; Peres & Palacios, ), overhunting can affect ple also hunted for medicinal purposes, recreation and retali- the ecological functionality of ecosystems (Cullen et al., ; ation. The most hunted and consumed species were the paca Wright et al., ; Peres et al., ), as well as local commu- Cuniculus paca, the nine-banded armadillo Dasypus novem- nities that depend on the consumption of wild meat for sub- cinctus and the collared peccary Pecari tajacu; threatened spe- sistence (Milner-Gulland et al., ). The importance of cies were rarely hunted. Opinions varied on whether wildlife hunting in household economies varies depending on socio- was declining or increasing; declines were generally attributed economic factors such as level of education (Nielsen & to hunting. -

Traditional People and Communities, Biodiversity, Water, and Climate Change August 2016

Challenges and Opportunities for Conservation, Agricultural Production, and Social Inclusion in the Cerrado Biome August 2016 Technical Annex: Traditional People and Communities, Biodiversity, Water, and Climate Change August 2016 This technical annex accompanies the “Challenges and Opportunities for Conservation, Agricultural Production, and Social Inclusion in the Cerrado Biome” report, developed for the Climate and Land Use Alliance by CEA Consulting. The full report and associated materials can be found at: www.climateandlandusealliance.org/reports/cerrado/ v Table of Contents Traditional people and communities 3 Biodiversity and protected areas 16 Water in the Cerrado 30 Climate change and the Cerrado 43 2 TRADITIONAL PEOPLE AND COMMUNITIES 3 Traditional people and communities in the Cerrado • The Matopiba region of the Cerrado is home to a rich diversity of cultures and people. It is an active area for family farmers and traditional forms of agriculture (including communal and extractive use of the land). It is also one of the poorest regions in the country. • The most representative groups in the Cerrado are: indigenous people, quilombolas (descendants of former African slaves), extractivists, geraizeiros (artisanal farmers in Minas Gerais and Bahia), and groups that subsist in riverine environments (ribeirinhos and vazanteiros). • In the Cerrado, traditional communities do not a strong political presence. Interviewees noted that this lack of capacity is a result of the lack of public and international attention historically given to the biome. • The initiatives aimed at protecting these communities are dispersed across the biome and there is a lack of coordination among them. • The most vocal groups tend to be completely opposed to the current agribusiness model, which is seen by many as a threat to the communities. -

Primates of the Jequitinhonha and Mucuri Valleys, Brazil

Primate Conservation 2018 (32): 95-108 Primates of the Valleys of the Rios Jequitinhonha and Mucuri, Brazil: Occurrence and Distribution Fabiano Rodrigues de Melo1,2,3, Fernando Lima4,5, Daniel da Silva Ferraz6,7, Michel Barros Faria6,7, Pedro Amaral de Oliveira8, Paola Cardias Soares9 and Adriano G. Chiarello10 1Unidade Acadêmica Especial Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal de Goiás (UFG), Jataí, Goiás, Brazil 2Departamento de Engenharia Florestal, Universidade Federal de Viçosa (UFV), Viçosa, Minas Gerais, Brazil 3Muriqui Instituto de Biodiversidade (MIB), Caratinga, Minas Gerais, Brazil 4IPÊ – Instituto de Pesquisas Ecológicas, Nazaré Paulista, São Paulo Brazil 5Pós-graduação em Ecologia e Biodiversidade, Instituto de Biociências, Universidade Estadual Paulista (UNESP), Rio Claro, São Paulo, Brazil 6Departamento de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade do Estado de Minas Gerais (UEMG), Carangola, Minas Gerais, Brazil 7Museu de Zoologia da Zona da Mata Mineira, Universidade do Estado de Minas Gerais (UEMG), Carangola, Minas Gerais, Brazil 8Instituto de Ciências Biológicas e da Saúde, Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil 9Pós-Graduação em Saúde e Produção Animal na Amazônia, Universidade Federal Rural da Amazônia (UFRA), Belém, Pará, Brazil 10Departamento de Biologia, Faculdade de Filosofia, Ciências e Letras, Universidade de São Paulo, Ribeirão Preto, São Paulo, Brazil Abstract: We report on a study of the occurrence and distribution of primates in three areas in the valleys of the rios Mucuri and Jequitinhonha in the states of Minas Gerais and Bahia. The areas were chosen on the basis of their classification as priority areas of high biological importance for conservation (numbered 213, 217, and 221) during a regional priority-setting workshop organized by the Brazilian government in 1999. -

The Experience of the GATI Project in Indigenous Lands in the Construction of Public Policies for Environmental and Territorial Management of Ils

The Project for Indigenous Territorial and Environmental Management (GATI) contributed to the recognition of Indigenous Lands (ILs) as protected areas essential for biodiversity conservation in Brazilian biomes, and strengthened traditional indigenous practices regarding management, sustainable use, and conservation of natural resources. In addition, it fostered indigenous leadership The Experience of the GATI Project in Indigenous Lands in the construction of public policies for environmental and territorial management of ILs. The Project was a joint effort of the Brazilian indigenous movement, the National Foundation for Indigenous Peoples (Funai), the Ministry of Environment (MMA), The Nature Conservancy (TNC), the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), and the Global Environment Facility (GEF). Articulação MATO GROSSO ARTICULAÇÃO DOS POVOS E ORGANIZAÇÕES INDÍGENAS DO NORDESTE, MINAS GERAIS E ESPÍRITO SANTO Instruments for Territorial and Empoderando vidas. www.theGEF.org Fortalecendo nações. Environmental Management PRESIDENCY OF THE NATIONAL FOUNDATION FOR INDIGENOUS PEOPLES Artur Nobre Mendes TERRITORIAL PROTECTION DIRECTORATE - DPT Walter Coutinho Jr. SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT DIRECTORATE - DPDS Patricia Chagas Neves ADMINISTRATION AND MANAGEMENT DIRECTORATE - DAGES Janice Queiroz de Oliveira GATI PROJECT MANAGEMENT UNIT NATIONAL PROJECT DIRECTOR - DPDS/FUNAI Patricia Chagas Neves NATIONAL PROJECT COORDINATOR - CGGAM/FUNAI Fernando de Luiz Brito Vianna UNDP PROJECT OFFICER Rose Diegues TECHNICAL COORDINATOR OF THE PROJECT - UNDP Robert Pritchard Miller PGTA COORDINATOR - UNDP Ney José Brito Maciel FINANCIAL COORDINATOR OF THE PROJECT - CGGAM/FUNAI Valéria do Socorro Novaes de Carvalho ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANTS - CGGAM/FUNAI Caio César de Sousa de Oliveira Sofia Morgana Siqueira Meneses Cataloguing in-Publication Data (CIP) (eDOC BRASIL, Belo Horizonte / MG) M152i Maciel, Ney José Brito Instruments for territorial and environmental management / Ney José Brito Maciel. -

Protecting Forests at the Expense of Native Grasslands: Land-Use Policy

G Model PECON-93; No. of Pages 6 ARTICLE IN PRESS Perspectives in Ecology and Conservation xxx (2018) xxx–xxx ´ Supported by Boticario Group Foundation for Nature Protection www.perspectecolconserv.com Research Letters Protecting forests at the expense of native grasslands: Land-use policy encourages open-habitat loss in the Brazilian cerrado biome a,b,∗ b,c d a Juliana Bonanomi , Fernando R. Tortato , Raphael Santos , Jerry M. Penha , e,f f Anderson Saldanha Bueno , Carlos A. Peres a Programa de Pós-Graduac¸ ão em Ecologia e Conservac¸ ão da Biodiversidade – Departamento de Ecologia e Botânica, Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso, Cuiabá, MT, Brazil b Instituto Conservac¸ ão Brasil, Chapada dos Guimarães, MT, Brazil c Panthera, 8 West 40th Street, 18th Floor, New York, USA d Departamento de Ciências da Computac¸ ão – Universidade Federal de MT, Brazil e Instituto Federal de Educac¸ ão, Ciência e Tecnologia Farroupilha, Júlio de Castilhos, RS, Brazil f Centre for Ecology, Evolution and Conservation, School of Environmental Sciences, University of East Anglia, Norwich NR4 7TJ, UK a a b s t r a c t r t i c l e i n f o Article history: The agricultural conversion of natural habitats is one of the main drivers of biodiversity loss worldwide. In Received 21 August 2018 2 the ∼2 million km Brazilian cerrado biome, a global biodiversity hotspot, vast areas have been converted Accepted 13 December 2018 into croplands and cattle pastures. Because the cerrado biome is overwhelmingly contained within private Available online xxx lands, Brazil’s environmental legislation should serve as a decisive instrument in protecting these natural ecosystems. -

Department of the Interior

Vol. 77 Friday, No. 130 July 6, 2012 Part IV Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service 50 CFR Part 17 Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Listing the Scarlet Macaw; Proposed Rule VerDate Mar<15>2010 18:25 Jul 05, 2012 Jkt 226001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4717 Sfmt 4717 E:\FR\FM\06JYP3.SGM 06JYP3 srobinson on DSK4SPTVN1PROD with PROPOSALS3 40222 Federal Register / Vol. 77, No. 130 / Friday, July 6, 2012 / Proposed Rules DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR as form letters), our preferred format is and Plants that contains substantial a spreadsheet in Microsoft Excel. scientific or commercial information Fish and Wildlife Service (2) By hard copy: Submit by U.S. mail that listing the species may be or hand-delivery to: Public Comments warranted, we make a finding within 12 50 CFR Part 17 Processing, Attn: FWS–R9–ES–2012– months of the date of receipt of the 0039; Division of Policy and Directives petition (‘‘12-month finding’’). In this [Docket No. FWS–R9–ES–2012–0039; Management; U.S. Fish and Wildlife finding, we determine whether the 4500030115] Service; 4401 N. Fairfax Drive, MS petitioned action is: (a) Not warranted, 2042–PDM; Arlington, VA 22203. (b) warranted, or (c) warranted, but RIN 1018–AY39 We will not accept comments by immediate proposal of a regulation Endangered and Threatened Wildlife email or fax. We will post all comments implementing the petitioned action is and Plants; Listing the Scarlet Macaw on http://www.regulations.gov. This precluded by other pending proposals to generally means that we will post any determine whether species are AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, personal information you provide us endangered or threatened, and Interior. -

Pantanal Conservation Area Brazil

PANTANAL CONSERVATION AREA BRAZIL The Pantanal Conservation Area is a cluster of four protected areas in southwest Brazil. The site covers 1.3% of Brazil's Pantanal, one of the world's largest freshwater wetlands, fed by the region's two major rivers, the Cuiabá and the Paraguai. It is the only area of the Pantanal that remains partially flooded during the dry season when it becomes a natural wildlife refuge. The abundance and diversity of its vegetation and animal life are spectacular and through the dispersal of nutrients the site is the region’s most important reserve for maintaining its fish stocks. It demonstrates on a small scale the ongoing ecological and biological processes of the Pantanal, and the inclusion of the Amolar Mountains gives the site a unique ecological gradient as well as a dramatic landscape. COUNTRY Brazil NAME Pantanal Conservation Area NATURAL WORLD HERITAGE SERIAL SITE 2000: Inscribed on the World Heritage List under Natural Criteria vii, ix and x. STATEMENT OF OUTSTANDING UNIVERSAL VALUE [pending] The UNESCO World Heritage Committee issued the following statement at the time of inscription: Justification for Inscription Criteria (vii), (ix) and (x): The site is representative of the Greater Pantanal region. It demonstrates the on-going ecological and biological processes that occur in the Pantanal. The association of the Amolar Mountains with the dominant freshwater wetland ecosystems confers to the site a uniquely important ecological gradient as well as a dramatic landscape. The site plays a key role in the dispersion of nutrients to the entire basin and is the most important reserve for maintaining fish stocks in the Pantanal. -

Brazil-Protected Areas

OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: Brazil 2015 © OECD 2015 PART II Chapter 5 Protected areas Brazil has massively expanded its network of protected areas. This chapter presents progress in extending the terrestrial and marine areas under environmental protection. It examines achievements and challenges related to the management of protected areas, including in terms of financial sustainability. The chapter describes the role of protected areas in improving the quality of life of traditional communities. Finally, it discusses the opportunities of opening protected areas to the public for tourism, recreation and environmental education, and for sustainable forest management. 231 5. PROTECTED AREAS 1. Categories, extension and benefits of protected areas 1.1. The National System of Protected Areas Protected areas have a long history in Brazil and are a cornerstone of its biodiversity policy. In 2000, in an effort to improve effectiveness of protected areas and to better preserve its tropical rainforests, Brazil established the National System of Protected Areas (SNUC), or conservation units, as such areas are known in the country.1 SNUC integrated the heterogeneous landscape of protected areas, including those established by federal, state and municipal governments as well as those proposed by private actors (individuals, companies, non-government organisations), into one national system. It provided a common definition of protected areas and a framework for co-ordinated management and implementation at different levels of government.