Cooperation of Amazon Countries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plant Diversity and Composition Changes Along an Altitudinal Gradient in the Isolated Volcano Sumaco in the Ecuadorian Amazon

diversity Article Plant Diversity and Composition Changes along an Altitudinal Gradient in the Isolated Volcano Sumaco in the Ecuadorian Amazon Pablo Lozano 1,*, Omar Cabrera 2 , Gwendolyn Peyre 3 , Antoine Cleef 4 and Theofilos Toulkeridis 5 1 1 Herbario ECUAMZ, Universidad Estatal Amazónica, Km 2 2 vía Puyo Tena, Paso Lateral, 160-150 Puyo, Ecuador 2 Dpto. de Ciencias Biológicas, Universidad Técnica Particular de Loja, San Cayetano Alto s/n, 110-104 Loja, Ecuador; [email protected] 3 Dpto. de Ingeniería Civil y Ambiental, Universidad de los Andes, Cra. 1E No. 19a-40, 111711 Bogotá, Colombia; [email protected] 4 IBED, Paleoecology & Landscape ecology, University of Amsterdam, Science Park 904, 1098 HX Amsterdam, The Netherlands; [email protected] 5 Universidad de las Fuerzas Armadas ESPE, Av. General Rumiñahui s/n, P.O.Box, 171-5-231B Sangolquí, Ecuador; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +593-961-162-250 Received: 29 April 2020; Accepted: 29 May 2020; Published: 8 June 2020 Abstract: The paramo is a unique and severely threatened ecosystem scattered in the high northern Andes of South America. However, several further, extra-Andean paramos exist, of which a particular case is situated on the active volcano Sumaco, in the northwestern Amazon Basin of Ecuador. We have set an elevational gradient of 600 m (3200–3800 m a.s.l.) and sampled a total of 21 vegetation plots, using the phytosociological method. All vascular plants encountered were typified by their taxonomy, life form and phytogeographic origin. In order to determine if plots may be ensembled into vegetation units and understand what the main environmental factors shaping this pattern are, a non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) analysis was performed. -

Supplementary Material Clariss Domin Drechs

CLARISSA ROSA et al. LONG TERM CONSERVATION IN BRAZIL SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Table SI. Location of sites of the Brazilian Program for Biodiversity Research network. Type id Latitude Longitude Site name CLARISSA ROSA, FABRICIO BACCARO, CECILIA CRONEMBERGER, JULIANA HIPÓLITO, CLAUDIA FRANCA BARROS, Module 1 -9.370 -69.9200 Chandless State Park DOMINGOS DE JESUS RODRIGUES, SELVINO NECKEL-OLIVEIRA, GERHARD E. OVERBECK, ELISANDRO RICARDO Running title: Long term Grid 2 1.010 -51.6500 Amapá National Forest DRECHSLER-SANTOS, MARCELO RODRIGUES DOS ANJOS, ÁTILLA C. FERREGUETTI, ALBERTO AKAMA, MARLÚCIA conservation in Brazil Module 3 -3.080 -59.9600 Federal University of Amazonas BONIFÁCIO MARTINS, WALFRIDO MORAES TOMAS, SANDRA APARECIDA SANTOS, VANDA LÚCIA FERREIRA, CATIA Grid 4 -2.940 -59.9600 Adolpho Ducke Forest Reserve NUNES DA CUNHA, JERRY PENHA, JOÃO BATISTA DE PINHO, SUZANA MARIA SALIS, CAROLINA RODRIGUES DA Academy Section: Ecosystems Module 5 -5.610 -67.6000 Médio Juruá COSTA DORIA, VALÉRIO D. PILLAR, LUCIANA R. PODGAISKI, MARCELO MENIN, NARCÍSIO COSTA BÍGIO, SUSAN Grid 6 -1.760 -61.6200 Jaú National Park ARAGÓN, ANGELO GILBERTO MANZATTO, EDUARDO VÉLEZ-MARTIN, ANA CAROLINA BORGES LINS E SILVA, THIAGO Module 7 -2.450 -59.7500 PDBFF fragments JUNQUEIRA IZZO, AMANDA FREDERICO MORTATI, LEANDRO LACERDA GIACOMIN, THAÍS ELIAS ALMEIDA, THIAGO e20201604 Grid 8 -1.780 -59.2700 Uatumã Biological Reserve ANDRÉ, MARIA AUREA PINHEIRO DE ALMEIDA SILVEIRA, ANTÔNIO LAFFAYETE PIRES DA SILVEIRA, MARILUCE Grid 9 -2.660 -60.0600 Experimental Farm from UFAM REZENDE MESSIAS, MARCIA C. M. MARQUES, ANDRE ANDRIAN PADIAL, RENATO MARQUES, YOUSZEF O.C. BITAR, 93 Grid 10 -3.030 -60.3700 Anavilhanas National Park MARCOS SILVEIRA, ELDER FERREIRA MORATO, RUBIANI DE CÁSSIA PAGOTTO, CHRISTINE STRUSSMANN, RICARDO (2) 93(2) Module 11 -3.090 -55.5200 BR-163 M08 BOMFIM MACHADO, LUDMILLA MOURA DE SOUZA AGUIAR, GERALDO WILSON FERNANDES YUMI OKI, SAMUEL Module 12 -4.080 -60.6700 Tupana NOVAIS, GUILHERME BRAGA FERREIRA, FLÁVIA RODRIGUES BARBOSA, ANA C. -

Guide to the Betty J. Meggers and Clifford Evans Papers

Guide to the Betty J. Meggers and Clifford Evans papers Tyler Stump and Adam Fielding Funding for the processing of this collection was provided by the Smithsonian Institution's Collections Care and Preservation Fund. December 2015 National Anthropological Archives Museum Support Center 4210 Silver Hill Road Suitland, Maryland 20746 [email protected] http://www.anthropology.si.edu/naa/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 5 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 5 Bibliography...................................................................................................................... 6 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 6 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 8 Series 1: Personal, 1893-2012................................................................................. 8 Series 2: Writings, 1944-2011............................................................................... -

Green Economy in Amapá State, Brazil Progress and Perspectives

Green economy in Amapá State, Brazil Progress and perspectives Virgilio Viana, Cecilia Viana, Ana Euler, Maryanne Grieg-Gran and Steve Bass Country Report Green economy Keywords: June 2014 green growth; green economy policy; environmental economics; participation; payments for environmental services About the author Virgilio Viana is Chief Executive of the Fundação Amazonas Sustentável (Sustainable Amazonas Foundation) and International Fellow of IIED Cecilia Viana is a consultant and a doctoral student at the Center for Sustainable Development, University of Brasília Ana Euler is President-Director of the Amapá State Forestry Institute and Researcher at Embrapa-AP Maryanne Grieg-Gran is Principal Researcher (Economics) at IIED Steve Bass is Head of IIED’s Sustainable Markets Group Acknowledgements We would like to thank the many participants at the two seminars on green economy in Amapá held in Macapá in March 2012 and March 2013, for their ideas and enthusiasm; the staff of the Fundação Amazonas Sustentável for organising the trip of Amapá government staff to Amazonas; and Laura Jenks of IIED for editorial and project management assistance. The work was made possible by financial support to IIED from UK Aid; however the opinions in this paper are not necessarily those of the UK Government. Produced by IIED’s Sustainable Markets Group The Sustainable Markets Group drives IIED’s efforts to ensure that markets contribute to positive social, environmental and economic outcomes. The group brings together IIED’s work on market governance, business models, market failure, consumption, investment and the economics of climate change. Published by IIED, June 2014 Virgilio Viana, Cecilia Viana, Ana Euler, Maryanne Grieg-Gran and Steve Bass. -

Conservation Versus Development at the Iguacu National Park, Brazil1

CONSERVATION VERSUS DEVELOPMENT AT THE IGUACU NATIONAL PARK, BRAZIL1 Ramon Arigoni Ortiz a a Research Professor at BC3 – Basque Centre for Climate Change – Bilbao – Spain Alameda Urquijo, 4 Piso 4 – 48009 – [email protected] Abstract The Iguacu National Park is a conservation unit that protects the largest remnant area of the Atlantic Rainforest in Brazil. The Colono Road is 17.6 km long road crossing the Iguacu National Park that has been the motive of dispute between environmentalists, government bodies and NGOs defending the closure of the Colono Road; and organised civil institutions representing the population of the surrounding cities defending its opening. In October 2003, 300 people invaded the Park in an attempt to remove the vegetation and reopen the road, which was prevented by members of the Brazilian Army and Federal Police. Those who advocate the reopening of the Colono Road claim significant economic losses imposed on the surrounding cities. This paper investigates this claim and concludes that a possible reopening of the Colono Road cannot be justified from an economic perspective. Keywords: Iguacu Park; Brazil; Colono Road; economic development; environmental degradation; valuation; cost-benefit analysis 1 WWF-Brazil provided the financial support to this work, which I am grateful. However, WWF-Brazil is not responsible for the results and opinions in this study. I am also grateful to two anonymous referees for their constructive comments, corrections and suggestions. The remaining errors and omissions are responsibility of the author solely. Ambientalia vol. 1 (2009-2010) 141-160 1 Arigoni, R. 1. INTRODUCTION sentence. The Colono Road remained closed until The Iguacu National Park is a conservation May 1997 when an entity named ´Friends of the unit located in Parana State, south region of Brazil Park´ (Movimento de Amigos do Parque) (Figure 1), comprising an area of 185,000 ha. -

Tourism in Continental Ecuador and the Galapagos Islands: an Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) Perspective

water Article Tourism in Continental Ecuador and the Galapagos Islands: An Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) Perspective Carlos Mestanza-Ramón 1,2,3,* , J. Adolfo Chica-Ruiz 1 , Giorgio Anfuso 1 , Alexis Mooser 1,4, Camilo M. Botero 5,6 and Enzo Pranzini 7 1 Facultad de Ciencias del Mar y Ambientales, Universidad de Cádiz, Polígono Río San Pedro s/n, 11510 Puerto Real, Cádiz, Spain; [email protected] (J.A.C.-R.); [email protected] (G.A.); [email protected] (A.M.) 2 Escuela Superior Politécnica de Chimborazo, Sede Orellana, YASUNI-SDC Research Group, El Coca EC220001, Ecuador 3 Instituto Tecnologico Supeior Oriente, La Joya de los Sachas 220101, Orellana, Ecuador 4 Dipartimento di Scienze e Tecnologie, Università di Napoli Parthenope, 80143 Naples, Italy 5 Grupo Joaquín Aarón Manjarrés, Escuela de Derecho, Universidad Sergio Arboleda, Santa Marta 470001, Colombia; [email protected] 6 Grupo de Investigación en Sistemas Costeros, PlayasCorp, Santa Marta 470001, Colombia 7 Dipartimento di Scienze della Terra, Università di Firenze, 50121 Firenze, Italy; enzo.pranzini@unifi.it * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected]; Tel.: +593-9-9883-0801 Received: 28 April 2020; Accepted: 6 June 2020; Published: 9 June 2020 Abstract: Tourism in coastal areas is becoming increasingly important in Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) as an integrated approach that balances the requirements of different tourist sectors. This paper analyzes ICZM in continental Ecuador and the Galapagos Islands from the perspective of the 3S tourism, and presents its strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT). The methodology used was based on a literature review of ten aspects of the highest relevance to ICZM, i.e., Policies, Regulations, Responsibilities, Institutions, Strategies and Instruments, Training, Economic Resources, Information, Education for Sustainability, and Citizen Participation. -

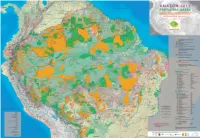

Mapaamazonia2012-Deforestationing

Amazon and human population Bolivia Brasil Colombia Ecuador Guyana Guyane Française Perú Suriname Venezuela total Amazon Protected Areas and Indigenous Territories % of the national % of the national % of the national % of the national % of the national % of the national % of the national % of the national % of the national % of the Amazon total total total total total total total total total total In Amazon the protection of socioenvironmental diversity is being consolidated through the recognition of the territorial rights of indigenous peoples A M A Z O N 2012 Total population and the constitution of a varied set of protected areas. These conservation strategies have been expanding over recent years and today cover a 8,274,325 - 191,480,630 - 42,090,502 - 14,483,499 - 751,000 - 208,171 - 28,220,764 - 492,829 - 27,150,095 - 313,151,815 (nº of inhabitants) surface area of 3,502,750 km2 – 2,144,412 km2 in Indigenous Territories and 1,696,529 km2 in Protected Natural Areas, with an overlap of 336,365 2 Amazon population km between them – which corresponds to 45% of the region. PROTECTED AREAS and INDIGENOUS TERRITORIES 1,233,727 14.9% 23,654,336 12.4% 1,210,549 2.9% 739,814 5.1% 751,000 100.0% 208,171 100.0% 3,675,292 13.0% 492,829 100.0% 1,716,984 6.3% 33,682,702 10.8% (nº of inhabitants) The challenge faced in terms of attaining the objectives of strengthening the cultural and biological diversity of Amazon, represented in indigenous Total area of the country (km2) 1,098,581 - 8,514,876 - 1,141,748 - 249,041 - 214,969 - 86,504 - 1,285,215 - 163,820 - 916,445 - 13,671,199 territories and protected areas, encompasses a variety of aspects. -

Road Impact on Habitat Loss Br-364 Highway in Brazil

ROAD IMPACT ON HABITAT LOSS BR-364 HIGHWAY IN BRAZIL 2004 to 2011 ROAD IMPACT ON HABITAT LOSS BR-364 HIGHWAY IN BRAZIL 2004 to 2011 March 2012 Content Acknowledgements ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................................... 5 Area of Study ............................................................................................................................................... 6 Habitat Change Monitoring ........................................................................................................................ 8 Previous studies ...................................................................................................................................... 8 Terra-i Monitoring in Brazil ..................................................................................................................... 9 Road Impact .......................................................................................................................................... 12 Protected Areas ..................................................................................................................................... 15 Carbon Stocks and Biodiversity ............................................................................................................. 17 Future Habitat Change Scenarios ............................................................................................................ -

Brazilian Amazon)

BRAZILIAN FORESTRY LEGISLATION AND TO COMBAT DEFORESTATION GOVERNMENT POLICIES IN THE AMAZON (BRAZILIAN AMAZON) THIAGO BANDEIRA CASTELO1 1 Introduction The forest legislation can be understood as a set of laws governing the relations of exploitation and use of forest resources. In Brazil, the first devices aimed at protected areas or resources have his record even in the colonial period, where the main objective was to guarantee control over the management of certain features such as vegetation, water and soil. Since then, the forest legislation has been undergoing constant changes (Medeiros, 2005) that directly affect the actors linked to the management, as the te- chnical institutions that monitor and control the exploitation of environmental areas, as well as researchers working in the area. In this scenario, the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA) (Law 7,735/1989) has been active in protecting the environment, ensuring the sustainable use of natural resources and promoting environmental quality nationwide. However, the need for decentralization of administrative actions of IBAMA, due to the large size of Brazil that overloads the supervisory actions of the body, led to publication of the Law 11,284/2006 of public forest management, which regulates the management decentralization process Union forest to the states and municipalities. Subsequent to this, the rural actors such as farmers and entrepreneurs with political support from government wards opened the discussions on the reform of the main legal instrument of legislation - The Forest Code. New forms that aim to address the growing need of the country in parallel with the environmental protection have been placed under discussion. -

Sediment Yields and Erosion Rates in the Napo River Basin: an Ecuadorian Andean Amazon Tributary

Sediment Transfer through the Fluvial System (Proceedings of a symposium held in Moscow, August 2004). 220 IAHS Publ. 288, 2004 Sediment yields and erosion rates in the Napo River basin: an Ecuadorian Andean Amazon tributary A. LARAQUE1, C. CERON1, E. ARMIJOS2, R. POMBOSA2, P. MAGAT1 & J. L. GUYOT3 1 HYBAM (UR154 LMTG), IRD - BP 64 501, F-34394 Montpellier Cedex 5, France [email protected] 2 INAMHI –700 Iñaquito y Correa, Quito, Ecuador 3 HYBAM (UR154 LMTG), IRD – Casilla 18 1209, Lima18, Peru Abstract This paper presents the first results obtained by the HYBAM project in the Napo River drainage basin in Ecuador during the period 2001–2002. Three gauging stations were installed in the basin to monitor suspended sediment yields, of which two are located in the Andean foothills and the third station on the Ecuador–Peru border in the Amazonian plain. At the confluence of the Coca and Napo rivers, the suspended sediment yield transported from the Andes Mountains is 13.6 106 t year-1 (766 t km-2 year-1). At the Nuevo Rocafuerte station 210 km downstream, the susp- ended sediment yield reaches 24.2 106 t year-1 for an annual mean discharge of 2000 m3 s-1. These values indicate intensive erosion processes in the Napo Andean foreland basin between the Andean foothills and the Nuevo Rocafuerte station, estimated to be 900 t km-2 year-1. These high rates of erosion are the result of the geodynamic uplift of the foreland. Keywords Amazon Basin; Andes; Ecuador; erosion; hydrology; Napo River; suspended sediment INTRODUCTION Most (95%) of the sediment discharged to the Atlantic Ocean by the Amazon River comes from the Andes Mountains although the range only covers 12% of the surface area of the Amazon basin. -

UNEP Frontiers 2016 Report: Emerging Issues of Environmental Concern

www.unep.org United Nations Environment Programme P.O. Box 30552, Nairobi 00100, Kenya Tel: +254-(0)20-762 1234 Fax: +254-(0)20-762 3927 Email: [email protected] web: www.unep.org UNEP FRONTIERS 978-92-807-3553-6 DEW/1973/NA 2016 REPORT Emerging Issues of Environmental Concern 2014 © 2016 United Nations Environment Programme ISBN: 978-92-807-3553-6 Job Number: DEW/1973/NA Disclaimer This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit services without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. UNEP would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source. No use of this publication may be made for resale or any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the United Nations Environment Programme. Applications for such permission, with a statement of the purpose and extent of the reproduction, should be addressed to the Director, DCPI, UNEP, P.O. Box 30552, Nairobi, 00100, Kenya. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNEP concerning the legal status of any country, territory or city or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. For general guidance on matters relating to the use of maps in publications please go to: http://www.un.org/Depts/Cartographic/english/htmain.htm Mention of a commercial company or product in this publication does not imply endorsement by the United Nations Environment Programme. -

Executive Summary of the National Action Plan For

EXECUTIVEEXECUTIVE SUMMARYSUMMARY OFOF THETHE NATIONALNATIONAL ACTIONACTION PLANPLAN FORFOR THETHE CONSERVATIONCONSERVATION OFOF MURIQUISMURIQUIS The mega-diverse country of Brazil is responsible for managing the largest natural patrimony in the world. More than 120,000 species of animals oc- cur throughout the country. Among these species, 627 are registered on the Official List of Brazilian Fauna Threatened with Extinction. The most affected Biome is the Atlantic Forest, within which 50% of the Critically Endangered mammalian species are primates endemic to this biome. Carla de Borba Possamai The Chico Mendes Institute is responsible for the development of strat- egies for the conservation of species of Brazilian fauna, evaluation of the conservation status of Brazilian fauna, publication of endangered species lists and red books and the development, implementation and monitoring of National Action Plans for the conservation of endangered species. Action plans are management tools for conservation of biodiversity and aligning strategies with different institutional stakeholders for the recovery and conservation of endangered species. The Joint Ordinance No. 316 of Septem- ber 9, 2009, was established as the legal framework to implement strategies. It indicates that action plans together with national lists of threatened species and red books, constitute one of the instruments of implementation of the National Biodiversity Policy (Decree 4.339/02). TAXANOMIC CLASSIFICATION Phylum: Chordata - Class: Mammalia - Order: Primates Family: Atelidae Gray, 1825 - Subfamily: Atelinae Gray, 1825 Genus: Brachyteles Spix, 1823 Species: Brachyteles arachnoides (E. Geoffroy, 1806) Brachyteles hypoxanthus (Kuhl, 1820) POPULAR NAMES Popular names include: Muriqui, Mono Carvoeiro, Mono, Miriqui, Buriqui, Buriquim, Mariquina or Muriquina. In English, they are also known as Woolly Spider Monkeys.