Psychiatric Hospitals in Uganda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prevalence of Maternal Near Miss and Community-Based Risk Factors in Central Uganda

International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics 135 (2016) 214–220 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ijgo CLINICAL ARTICLE Prevalence of maternal near miss and community-based risk factors in Central Uganda Elizabeth Nansubuga a,b,c,⁎,NatalAyigaa,CherylA.Moyerd a Population Research and Training Unit, North West University, Mafikeng, South Africa b Department of Population Studies, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda c African Studies Center, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA d Departments of Learning Health Sciences and Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA article info abstract Article history: Objective: To examine the prevalence of maternal near-miss (MNM) and its associated risk factors in a community Received 4 November 2015 setting in Central Uganda. Methods: A cross-sectional research design employing multi-stage sampling collected Received in revised form 19 May 2016 data from women aged 15–49 years in Rakai, Uganda, who had been pregnant in the 3 years preceding the survey, Accepted 26 July 2016 conducted between August 10 and December 31, 2013. Additionally, in-depth interviews were conducted. WHO-based disease and management criteria were used to identify MNM. Binary logistic regression was used to Keywords: predict MNM risk factors. Content analysis was performed for qualitative data. Results: Survey data were collected Maternal near-miss from 1557 women and 40 in-depth interviews were conducted. The MNM prevalence was 287.7 per 1000 pregnan- Pregnancy complications Prevalence cies; the majority of MNMs resulted from hemorrhage. Unwanted pregnancies, a history of MNM, primipara, Risk factors pregnancy danger signs, Banyakore ethnicity, and a partner who had completed primary education only were asso- Uganda ciated with increased odds of MNM (all P b 0.05). -

Evaluation of Antiretroviral Therapy Information System in Mbale Regional Referral Hospital, Uganda

EVALUATION OF ANTIRETROVIRAL THERAPY INFORMATION SYSTEM IN MBALE REGIONAL REFERRAL HOSPITAL, UGANDA. PETER OLUPOT-OLUPOT A mini-thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Public Health in the School of Public Health, University of the Western Cape. SUPERVISOR: DR. GAVIN REAGON February 2009 1 KEY WORDS Health Information Systems HIV/AIDS ART Data Quality Timeliness Data Accuracy Data analysis Data use Use of information Availability 2 ACRONYMS AIDS Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome ACP AIDS Control Program ART Antiretroviral Therapy ART-IS Antiretroviral Therapy Information System ARV Antiretroviral CD4 Cluster of Differentiation 4 CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention EBR Electronic Based Records GFATM Global Fund to fight AIDS, Tuberculosis & Malaria GOU Government of Uganda IDC Infectious Disease Clinic IMR Infant Mortality Rate HAART Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy HIS Health Information Systems HISP Health Information System Project HIT Health Information Technology HIV Human Immunodeficiency Virus HMIS Health Management Information Systems MAP Multi-country AIDS Program MMR Maternal Mortality Rate MOH Ministry of Health MPH Master of Public Health MRRH Mbale Regional Referral Hospital 3 NGO Non Governmental organization OI Opportunistic Infection OpenMRS Open Medical Record System PBR Paper Based Record PDA Personal Digital Assistant PEPFAR President’s (USA) Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief PLWA People Living with HIV/AIDS RHINONET Routine Health Information Network SOPH School of Public Health SSA Sub – Saharan Africa STI Sexually Transmitted Infection TASO The AIDS Support Organization TB Tuberculosis U5MR Under Five Mortality Rate UN United Nations UNAIDS United Nations Joint Program on AIDS UWC University of the Western Cape VCT Voluntary Counseling and Testing WHO World Health Organization 4 About the Evaluation The ART – IS at Mbale regional referral hospital is still an infant system which has been in operation for only 3 years. -

Erin's Guide to Gulu

Edited 10/2019 GHCE Global Health Clinical Elective 2020 GUIDE TO YOUR CLINICAL ELECTIVE IN Gulu, UGANDA Disclaimer: This booklet is provided as a service to UW students going to Gulu, Uganda, based on feedback from previous students. The Global Health Resource Center is not responsible for any inaccuracies or errors in the booklet's contents. Students should use their own common sense and good judgment when traveling, and obtain information from a variety of reliable sources. Please conduct your own research to ensure a safe and satisfactory experience. TABLE OF CONTENTS Contact Information 3 Entry Requirements 5 Country Overview 6 Packing Tips 8 Money 13 Communication 13 Travel to/from Gulu 14 Phrases 16 Food 16 Budgeting 17 Fun 17 Health and Safety Considerations 18 How not to make an ass of yourself 19 Map 21 Cultural Adjustment 24 Guidelines for the Management of Body Fluid Exposure 26 2 CONTACT INFORMATION - U.S. Name Address Telephone Email or Website UW In case of emergency: +1-206-632-0153 www.washington.edu/glob International 1. Notify someone in country (24-hr hotline) alaffairs/emergency/ Emergency # 2. Notify CISI (see below) 3. Call 24-hr hotline [email protected] 4. May call Scott/McKenna [email protected] GHCE Director(s) Dr. Scott +206-473-0392 [email protected] McClelland (Scott, cell) [email protected] 001-254-731- Dr. McKenna 490115 (Scott, Eastment Kenya) GHRC Director Daren Wade Harris Hydraulics +1-206-685-7418 [email protected] (office) Building, Room [email protected] #315 +1-206-685-8519 [email protected] 1510 San Juan (fax) Road Seattle, WA 98195 Insurance CISI 24/7 call center [email protected] available at 888-331- nce.com 8310 (toll-free) or 240-330-1414 (accepts Collect calls) Hall Health Anne Terry, 315 E. -

Ministry of Health

UGANDA PROTECTORATE Annual Report of the MINISTRY OF HEALTH For the Year from 1st July, 1960 to 30th June, 1961 Published by Command of His Excellency the Governor CONTENTS Page I. ... ... General ... Review ... 1 Staff ... ... ... ... ... 3 ... ... Visitors ... ... ... 4 ... ... Finance ... ... ... 4 II. Vital ... ... Statistics ... ... 5 III. Public Health— A. General ... ... ... ... 7 B. Food and nutrition ... ... ... 7 C. Communicable diseases ... ... ... 8 (1) Arthropod-borne diseases ... ... 8 (2) Helminthic diseases ... ... ... 10 (3) Direct infections ... ... ... 11 D. Health education ... ... ... 16 E. ... Maternal and child welfare ... 17 F. School hygiene ... ... ... ... 18 G. Environmental hygiene ... ... ... 18 H. Health and welfare of employed persons ... 21 I. International and port hygiene ... ... 21 J. Health of prisoners ... ... ... 22 K. African local governments and municipalities 23 L. Relations with the Buganda Government ... 23 M. Statutory boards and committees ... ... 23 N. Registration of professional persons ... 24 IV. Curative Services— A. Hospitals ... ... ... ... 24 B. Rural medical and health services ... ... 31 C. Ambulances and transport ... ... 33 á UGANDA PROTECTORATE MINISTRY OF HEALTH Annual Report For the year from 1st July, 1960 to 30th June, 1961 I.—GENERAL REVIEW The last report for the Ministry of Health was for an 18-month period. This report, for the first time, coincides with the Government financial year. 2. From the financial point of view the year has again been one of considerable difficulty since, as a result of the Economy Commission Report, it was necessary to restrict the money available for recurrent expenditure to the same level as the previous year. Although an additional sum was available to cover normal increases in salaries, the general effect was that many economies had to in all be made grades of staff; some important vacancies could not be filled, and expansion was out of the question. -

Free Mover Clinical Clerkships

FREE MOVER CLINICAL CLERKSHIPS Students interested in spending a clerkship activity abroad without participating in the Erasmus+ programs can enroll as Free-Movers (Fee-paying Visiting Students or Independent Students or Contract Students) at some foreign University hospitals where they can attend clinical rotations. The Free-Mover Clinical Clerkship Period is an optional part of the medical course and as such must be accounted for. Students not willing to participate still have to attend clinical rotations at the University of Milan. The Clerkship abroad represents a mutual contract between Supervisor and Student and is subject to supervision by the Faculty. In this document, there is the list of possible destinations and university hospitals in which the clinical clerkship period can be performed. For some of the destinations, students are advised to clearly declare their student status, as they may be allowed to participate only as observers and not and interns. 1 AFRICA Egypt Ethiopia Benin Botswana IvoryCoast Ghana Cameroon Kenya Libya Morocco Namibia Nigeria Rwanda Zambia Senegal Sudan SouthAfrica Tanzania Tunisia Uganda Zimbabwe ASIA China India Indonesia Japan Cambodia Malaysia Mongolia Nepal Philippines Singapore SriLanka SouthKorea Taiwan Thailand Vietnam 2 THE MIDDLE EAST Bahrain Iran Israel Jordan Qatar Lebanon Oman Palestine SaudiArabia Syria United Arab Emirates OCEANIA Australia Adelaide Canberra Melbourne Newcastle NewSouthWales Perth Queensland Sydney Tasmania New Zealand EUROPE Belgium Bosnia-Herzigowina Bulgaria Denmark -

Using Life Histories to Explore Gendered Experiences of Conflict in Gulu District, Northern Uganda: Implications for Post-Conflict Health Reconstruction

South African Review of Sociology ISSN: 2152-8586 (Print) 2072-1978 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rssr20 Using life histories to explore gendered experiences of conflict in Gulu District, northern Uganda: Implications for post-conflict health reconstruction Sarah N. Ssali & Sally Theobald To cite this article: Sarah N. Ssali & Sally Theobald (2016) Using life histories to explore gendered experiences of conflict in Gulu District, northern Uganda: Implications for post- conflict health reconstruction, South African Review of Sociology, 47:1, 81-98, DOI: 10.1080/21528586.2015.1132634 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/21528586.2015.1132634 © 2016 The Author(s). Published by Unisa Published online: 24 Mar 2016. Press and Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group Submit your article to this journal Article views: 145 View related articles View Crossmark data Citing articles: 8 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rssr20 USING LIFE HISTORIES TO EXPLORE GENDERED EXPERIENCES OF CONFLICT IN GULU DISTRICT, NORTHERN UGANDA: IMPLICATIONS FOR POST-CONFLICT HEALTH RECONSTRUCTION Sarah N. Ssali School of Women and Gender Studies Makerere University [email protected]; [email protected] Sally Theobald Department of International Public Health Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine [email protected] ABSTRACT The dearth of knowledge about what life was like for different women and men, communities and institutions during conflict has caused many post-conflict developers to undertake reconstruction using standardised models that may not always reflect the realities of the affected populations. -

Download Download

Open Access ORIGINAL RESEARCH Assessment of the impact of the new paediatric surgery unit and the COSECSA training programme at Mbarara Hospital, Uganda Anne W. Shikanda, Martin S. Situma Pediatric Surgery Department, Mbarara University Teaching Hospital, Mbarara, Uganda Correspondence: Dr Anne W. Shikanda ([email protected]) © 2019 A.W. Shikanda & M.S. Situma. This open access article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/ East Cent Afr J Surg. 2019 Apr;24(1):133–139 licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. https://dx.doi.org/10.4314/ecajs.v24i2.10 Abstract Background This study aimed to assess the impact of a new pediatric surgical unit (PSU) established upcountry in a unique way in a govern- ment hospital with a non-governmental organization as the main stakeholder. The unit is run by one pediatric surgeon trained through COSECSA. It is the second PSU in the country. This PSU brought pediatric surgical services and training closer to the Mbarara community. Methods The study was conducted at Mbarara regional referral hospital (MRRH). It was a cross-sectional mixed design study. For the qual- itative arm, Key Informant interviews were done with the main stakeholders who established the PSU. Impact on training was assessed using a questionnaire to former postgraduate trainees (Alumni). Quantitative arm assessed number of surgeries by a historical audit of hospital operating room registers comparing volume of surgeries before and after the establishment of the unit. -

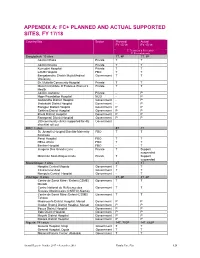

Appendix A: Fc+ Planned and Actual Supported Sites, Fy 17/18

APPENDIX A: FC+ PLANNED AND ACTUAL SUPPORTED SITES, FY 17/18 Country/Site Sector Planned Actual FY 17/18 FY 17/18 T: Treatment & Prevention P: Prevention-only Bangladesh: 15 sites 7T, 4P 7T, 8P Ad-Din Dhaka Private T T Ad-Din Khulna Private T T Kumudini Hospital Private T T LAMB Hospital FBO T T Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical Government T T University Dr. Muttalib Community Hospital Private T T Mamm's Institute of Fistula & Women's Private T T Health Ad-Din Jashohor Private - P Hope Foundation Hospital NGO - P Gaibandha District Hospital Government - P Jhalakathi District Hospital Government - P Rangpur District Hospital Government P P Satkhira District Hospital Government P P Bhola District Hospital Government P P Ranagmati District Hospital Government P P 200 community clinics supported for 4Q Government checklist roll out DRC: 4 sites 5T 4T St. Joseph’s Hospital/Satellite Maternity FBO T T Kinshasa Panzi Hospital FBO T T HEAL Africa FBO T T Beniker Hospital FBO - T Imagerie Des Grands-Lacs Private T Support suspended Maternité Sans Risque Kindu Private T Support suspended Mozambique: 3 sites 2T 3T Hospital Central Maputo Government T T Clinica Cruz Azul Government T T Nampula Central Hospital Government - T WA/Niger: 9 sites 3T, 6P 3T, 6P Centre de Santé Mère / Enfant (CSME) Government T T Maradi Centre National de Référence des Government T T Fistules Obstétricales (CNRFO),Niamey Centre de Santé Mère /Enfant (CSME) Government T T Tahoua Madarounfa District Hospital, Maradi Government P P Guidan Roumji District Hospital, Maradi Government -

Planned Shutdown Web October 2020.Indd

PLANNED SHUTDOWN FOR SEPTEMBER 2020 SYSTEM IMPROVEMENT AND ROUTINE MAINTENANCE REGION DAY DATE SUBSTATION FEEDER/PLANT PLANNED WORK DISTRICT AREAS & CUSTOMERS TO BE AFFECTED Kampala West Saturday 3rd October 2020 Mutundwe Kampala South 1 33kV Replacement of rotten vertical section at SAFARI gardens Najja Najja Non and completion of flying angle at MUKUTANO mutundwe. North Eastern Saturday 3rd October 2020 Tororo Main Mbale 1 33kV Create Two Tee-offs at Namicero Village MBALE Bubulo T/C, Bududa Tc Bulukyeke, Naisu, Bukigayi, Kufu, Bugobero, Bupoto Namisindwa, Magale, Namutembi Kampala West Sunday 4th October 2020 Kampala North 132/33kV 32/40MVA TX2 Routine Maintenance of 132/33kV 32/40MVA TX 2 Wandegeya Hilton Hotel, Nsooda Atc Mast, Kawempe Hariss International, Kawempe Town, Spencon,Kyadondo, Tula Rd, Ngondwe Feeds, Jinja Kawempe, Maganjo, Kagoma, Kidokolo, Kawempe Mbogo, Kalerwe, Elisa Zone, Kanyanya, Bahai, Kitala Taso, Kilokole, Namere, Lusanjja, Kitezi, Katalemwa Estates, Komamboga, Mambule Rd, Bwaise Tc, Kazo, Nabweru Rd, Lugoba Kazinga, Mawanda Rd, East Nsooba, Kyebando, Tilupati Industrial Park, Mulago Hill, Turfnel Drive, Tagole Cresent, Kamwokya, Kubiri Gayaza Rd, Katanga, Wandegeya Byashara Street, Wandegaya Tc, Bombo Rd, Makerere University, Veterans Mkt, Mulago Hospital, Makerere Kavule, Makerere Kikumikikumi, Makerere Kikoni, Mulago, Nalweuba Zone Kampala East Sunday 4th October 2020 Jinja Industrial Walukuba 11kV Feeder Jinja Industrial 11kV feeders upgrade JINJA Walukuba Village Area, Masese, National Water Kampala East -

Health Sector Semi-Annual Monitoring Report FY2020/21

HEALTH SECTOR SEMI-ANNUAL BUDGET MONITORING REPORT FINANCIAL YEAR 2020/21 MAY 2021 Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development P.O. Box 8147, Kampala www.finance.go.ug MOFPED #DoingMore Health Sector: Semi-Annual Budget Monitoring Report - FY 2020/21 A HEALTH SECTOR SEMI-ANNUAL BUDGET MONITORING REPORT FINANCIAL YEAR 2020/21 MAY 2021 MOFPED #DoingMore Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS .............................................................................iv FOREWORD.........................................................................................................................vi EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................vii CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION .........................................................................................1 1.1 Background ........................................................................................................................1 CHAPTER 2: METHODOLOGY........................................................................................2 2.1 Scope ..................................................................................................................................2 2.2 Methodology ......................................................................................................................3 2.2.1 Sampling .........................................................................................................................3 -

Office of the Auditor General the Republic of Uganda

OFFICE OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA REPORT OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL ON THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS OF MBALE REGIONAL REFERRAL HOSPITAL FOR THE YEAR ENDED 30TH JUNE 2016 Table of Contents LIST OF ACROYNMS ................................................................................................................................................. 2 1.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................ 5 2.0 AUDIT OBJECTIVES ..................................................................................................................................... 5 3.0 AUDIT PROCEDURES PERFORMED .......................................................................................................... 6 4.0 ENTITY FINANCING ..................................................................................................................................... 6 5.0 FINDINGS ....................................................................................................................................................... 7 5.1 Categorization of Findings ............................................................................................................................... 7 5.2 Summary of Findings ....................................................................................................................................... 7 6.0 DETAILED AUDIT FINDINGS .................................................................................................................... -

Nakawa Division Grades

DIVISION PARISH VILLAGE STREET AREA GRADE NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BLOCK 1 TO24 LUTHULI 4TH CLOSE 2-9 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BLOCK 1 TO25 LUTHULI 1ST CLOSE 1-9 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BLOCK 1 TO26 LUTHULI 5TH CLOSE 1-9 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BLOCK 1 TO27 LUTHULI 2ND CLOSE 1-10 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BLOCK 1 TO28 LUTHULI RISE 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II MBUYA ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II MIZINDALO ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II MPANGA CLOSE 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II MUZIWAACO ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II PRINCESS ANNE DRIVE 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II ROBERT MUGABE ROAD. 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II BAZARRABUSA DRIVE 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II BINAYOMBA RISE 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II BINAYOMBA ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II BUGOLOBI STREET 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II FARADAY ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II FARADY ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II HUNTER CLOSE 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II KULUBYA CLOSE 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW I BANDALI RISE 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW I HANLON ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW I MUWESI ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW I NYONDO CLOSE 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW I SALMON RISE 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW I SPRING ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW I YOUNGER AVENUE 1 NAKAWA BUKOTO I KALONDA KISASI ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUKOTO I KALONDA SERUMAGA ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUKOTO I MUKALAZI KISASI ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUKOTO I MUKALAZI MUKALAZI ROAD 1 1 NAKAWA BUKOTO I MULIMIRA OFF MOYO CLOSE 1 NAKAWA BUKOTO I NTINDA- OLD KIRA ZONE NTINDA- OLD KIRA ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUKOTO I OLD KIRA ROAD BATAKA ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUKOTO I OLD KIRA ROAD LUTAYA