Prevalence of Maternal Near Miss and Community-Based Risk Factors in Central Uganda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Download

Open Access ORIGINAL RESEARCH Assessment of the impact of the new paediatric surgery unit and the COSECSA training programme at Mbarara Hospital, Uganda Anne W. Shikanda, Martin S. Situma Pediatric Surgery Department, Mbarara University Teaching Hospital, Mbarara, Uganda Correspondence: Dr Anne W. Shikanda ([email protected]) © 2019 A.W. Shikanda & M.S. Situma. This open access article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/ East Cent Afr J Surg. 2019 Apr;24(1):133–139 licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. https://dx.doi.org/10.4314/ecajs.v24i2.10 Abstract Background This study aimed to assess the impact of a new pediatric surgical unit (PSU) established upcountry in a unique way in a govern- ment hospital with a non-governmental organization as the main stakeholder. The unit is run by one pediatric surgeon trained through COSECSA. It is the second PSU in the country. This PSU brought pediatric surgical services and training closer to the Mbarara community. Methods The study was conducted at Mbarara regional referral hospital (MRRH). It was a cross-sectional mixed design study. For the qual- itative arm, Key Informant interviews were done with the main stakeholders who established the PSU. Impact on training was assessed using a questionnaire to former postgraduate trainees (Alumni). Quantitative arm assessed number of surgeries by a historical audit of hospital operating room registers comparing volume of surgeries before and after the establishment of the unit. -

Psychiatric Hospitals in Uganda

Psychiatric hospitals in Uganda A human rights investigation w www.mdac.org mentaldisabilityadvocacy @MDACintl Psychiatric hospitals in Uganda A human rights investigation 2014 December 2014 ISBN 978-615-80107-7-1 Copyright statement: Mental Disability Advocacy Center (MDAC) and Mental Health Uganda (MHU), 2014. All rights reserved. Contents Foreword ...................................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Executive summary ......................................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 1. Introduction, torture standards and hospitals visited.............................................................................................................................. 9 1(A). The need for human rights monitoring........................................................................................................................................................... 9 1(B). Uganda country profile .................................................................................................................................................................................... 10 1(C). Mental health ................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

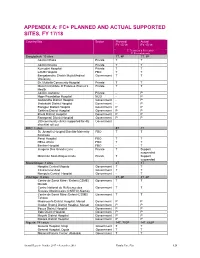

Appendix A: Fc+ Planned and Actual Supported Sites, Fy 17/18

APPENDIX A: FC+ PLANNED AND ACTUAL SUPPORTED SITES, FY 17/18 Country/Site Sector Planned Actual FY 17/18 FY 17/18 T: Treatment & Prevention P: Prevention-only Bangladesh: 15 sites 7T, 4P 7T, 8P Ad-Din Dhaka Private T T Ad-Din Khulna Private T T Kumudini Hospital Private T T LAMB Hospital FBO T T Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical Government T T University Dr. Muttalib Community Hospital Private T T Mamm's Institute of Fistula & Women's Private T T Health Ad-Din Jashohor Private - P Hope Foundation Hospital NGO - P Gaibandha District Hospital Government - P Jhalakathi District Hospital Government - P Rangpur District Hospital Government P P Satkhira District Hospital Government P P Bhola District Hospital Government P P Ranagmati District Hospital Government P P 200 community clinics supported for 4Q Government checklist roll out DRC: 4 sites 5T 4T St. Joseph’s Hospital/Satellite Maternity FBO T T Kinshasa Panzi Hospital FBO T T HEAL Africa FBO T T Beniker Hospital FBO - T Imagerie Des Grands-Lacs Private T Support suspended Maternité Sans Risque Kindu Private T Support suspended Mozambique: 3 sites 2T 3T Hospital Central Maputo Government T T Clinica Cruz Azul Government T T Nampula Central Hospital Government - T WA/Niger: 9 sites 3T, 6P 3T, 6P Centre de Santé Mère / Enfant (CSME) Government T T Maradi Centre National de Référence des Government T T Fistules Obstétricales (CNRFO),Niamey Centre de Santé Mère /Enfant (CSME) Government T T Tahoua Madarounfa District Hospital, Maradi Government P P Guidan Roumji District Hospital, Maradi Government -

Health Sector Semi-Annual Monitoring Report FY2020/21

HEALTH SECTOR SEMI-ANNUAL BUDGET MONITORING REPORT FINANCIAL YEAR 2020/21 MAY 2021 Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development P.O. Box 8147, Kampala www.finance.go.ug MOFPED #DoingMore Health Sector: Semi-Annual Budget Monitoring Report - FY 2020/21 A HEALTH SECTOR SEMI-ANNUAL BUDGET MONITORING REPORT FINANCIAL YEAR 2020/21 MAY 2021 MOFPED #DoingMore Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS .............................................................................iv FOREWORD.........................................................................................................................vi EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................vii CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION .........................................................................................1 1.1 Background ........................................................................................................................1 CHAPTER 2: METHODOLOGY........................................................................................2 2.1 Scope ..................................................................................................................................2 2.2 Methodology ......................................................................................................................3 2.2.1 Sampling .........................................................................................................................3 -

Traditional Eye Medicine Use in Microbial Keratitis In

Wellcome Open Research 2019, 4:89 Last updated: 22 AUG 2019 RESEARCH ARTICLE Traditional eye medicine use in microbial keratitis in Uganda: a mixed methods study [version 1; peer review: 1 approved, 1 approved with reservations] Simon Arunga 1,2, Allen Asiimwe3, Eunice Apio Olet4, Grace Kagoro-Rugunda4, Bosco Ayebazibwe5, John Onyango1, Robert Newton3,6, Astrid Leck 2, David Macleod 7, Victor H. Hu 2, Janet Seeley 3,8, Matthew J. Burton 2 1Department of Ophthalmology, Mbarara University of Science and Technology, Mbarara, Uganda 2International Centre for Eye Health, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, London, UK, WCIE 7TH, UK 3MRC/UVRI, LSHTM Uganda Research Unit, Entebbe, Entebbe, Uganda 4Department of Biology, Mbarara University of Science and Technology, Mbarara, Uganda 5Ruharo Eye Centre, Ruharo Mission Hospital, Mbarara, Uganda 6University of York, UK, York, YO10 5DD, UK 7Tropical Epidemiology Group, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, London, UK, WCIE 7TH, UK 8Department of Global Health and Development, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, London, UK, WCIE 7TH, UK First published: 06 Jun 2019, 4:89 ( Open Peer Review v1 https://doi.org/10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15259.1) Latest published: 06 Jun 2019, 4:89 ( https://doi.org/10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15259.1) Reviewer Status Abstract Invited Reviewers Background: Traditional eye medicine (TEM) is frequently used to treat 1 2 microbial keratitis (MK) in many parts of Africa. Few reports have suggested that this is associated with a worse outcome. We undertook this version 1 large prospective study to determine how TEM use impacts presentation published report report and outcome of MK and to explore reasons why people use TEM for 06 Jun 2019 treatment in Uganda. -

Atomic Energy Council Annual Report 2012/2013

Atomic Energy Council 1 Annual Report 2012/2013 ATOMIC ENERGY COUNCIL ANNUAL REPORT FOR 2012/2013 “To regulate the peaceful applications and management of ionizing radiation for the protection and safety of society and the environment from the dangers resulting from ionizing radiation” Atomic Energy Council 2 Annual Report 2012/2013 FOREWARD The Atomic Energy Council was established by the Atomic Energy Act, 2008, Cap. 143 Laws of Uganda, to regulate the peaceful applications of ionizing radiation in the country. The Council consists of the policy organ with five Council Members headed by the Chairperson appointed by the Minister and the full time Secretariat headed by the Secretary. The Council has extended services to various areas of the Country ranging from registering facilities that use radiation sources, authorization of operators, monitoring occupational workers, carrying out inspections in facilities among others. The Council made achievements which include establishing the Secretariat, gazetting of the Atomic Energy Regulations, 2012, developing safety guides for medical and industrial practices, establishing systems of notifications, authorizations and inspections, establishing national and international collaborations with other regulatory bodies and acquisition of some equipment among others. The Council has had funding as the major constraint to the implementation of the Act and the regulations coupled with inadequate equipment and insufficient administrative and technical staff. The Council will focus on institutional development, establishing partnerships and collaborations and safety and security of radioactive sources. The Council would like to thank the government and in particular the MEMD, the International Atomic Energy Agency, United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission and other organizations and persons who have helped Council in carrying out its mandate. -

Antibiotic Resistance in Uganda: Situation Analysis and Recommendations

UGANDA NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES Antibiotic Resistance in Uganda: Situation Analysis and Recommendations Antibiotic Resistance in Uganda: Situation Analysis and Recommendations a Uganda National Academy of Sciences A4 Lincoln House Makerere University P.O. Box 23911, Kampala, Uganda Tel: +256-414-53 30 44 Fax: +256-414-53 30 44 E-mail: [email protected] www.ugandanationalacademy.org This is a report of the Uganda National Academy of Sciences (UNAS). UNAS works to achieve improved prosperity and welfare for the people of Uganda by generating, SURPRWLQJVKDULQJDQGXVLQJVFLHQWL¿FNQRZOHGJHDQGE\JLYLQJHYLGHQFHEDVHGDGYLFH to government and civil society. UNAS was founded in 2000 and was granted a Charter E\+LV([FHOOHQF\WKH3UHVLGHQWRI8JDQGDLQ,WLVDQKRQRUL¿FDQGVHUYLFHRULHQWHG RUJDQL]DWLRQ IRXQGHG RQ SULQFLSOHV RI REMHFWLYLW\ VFLHQWL¿F ULJRU WUDQVSDUHQF\ PXWXDO respect, linkages and partnerships, independence, and the celebration of excellence. All rights reserved. Except as otherwise permitted by written agreement, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without the prior permission of the copyright owner, the Uganda National Academy of Sciences. Suggested citation: UNAS, CDDEP, GARP-Uganda, Mpairwe, Y., & Wamala, S. (2015). Antibiotic Resistance in Uganda: Situation Analysis and Recommendations (pp. 107). Kampala, Uganda: Uganda National Academy of Sciences; Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics & Policy. ISBN: 978-9970-424-10-8 © Uganda National Academy of Sciences, August 2015 Antibiotic Resistance in Uganda: Situation Analysis and Recommendations i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS $QWLPLFURELDOUHVLVWDQFH $05 KDVEHHQFODVVL¿HGDVDJOREDOKHDOWKWKUHDWWKDWWKUHDWHQV the gains achieved by anti-infectives. The world is therefore coming together to mobilize efforts to combat the problem. -

UG-08 24 A3 Fistula Supported Preventive Facilities by Partners

UGANDA FISTULA TREATMENT SERVICES AND SURGEONS (November 2010) 30°0'0"E 32°0'0"E 34°0'0"E Gulu Gulu Regional Referral Hospital Agago The Republic of Uganda Surgeon Repair Skill Status Kalongo General Hospital Soroti Ministry of Health Dr. Engenye Charles Simple Active Surgeon Repair Skill Status Dr. Vincentina Achora Not Active Soroti Regional Referral Hospital St. Mary's Hospital Lacor Surgeon Repair Skill Status 4°0'0"N Dr. Odong E. Ayella Complex Active Dr. Kirya Fred Complex Active 4°0'0"N Dr. Buga Paul Intermediate Active Dr. Bayo Pontious Simple Active SUDAN Moyo Kaabong Yumbe Lamwo Koboko Kaabong Hospital qÆ DEM. REP qÆ Kitgum Adjumani Hospital qÆ Kitgum Hospital OF CONGO Maracha Adjumani Hoima Hoima Regional Referral Hospital Kalongo Hospital Amuru Kotido Surgeon Repair Skill Status qÆ Arua Hospital C! Dr. Kasujja Masitula Simple Active Arua Pader Agago Gulu C! qÆ Gulu Hospital Kibaale Lacor Hospital Abim Kagadi General Hospital Moroto Surgeon Repair Skill Status Dr. Steven B. Mayanja Simple Active qÆ Zombo Nwoya qÆ Nebbi Otuke Moroto Hospital Nebbi Hospital Napak Kabarole Oyam Fort Portal Regional Referral Hospital Kole Lira Surgeon Repair Skill Status qÆ Alebtong Dr. Abirileku Lawrence Simple Active Lira Hospital Limited Amuria Dr. Charles Kimera Training Inactive Kiryandongo 2°0'0"N 2°0'0"N Virika General Hospital Bullisa Amudat HospitalqÆ Apac Dokolo Katakwi Dr. Priscilla Busingye Simple Inactive Nakapiripirit Amudat Kasese Kaberamaido Soroti Kagando General Hospital Masindi qÆ Soroti Hospital Surgeon Repair Skill Status Amolatar Dr. Frank Asiimwe Complex Visiting qÆ Kumi Hospital Dr. Asa Ahimbisibwe Intermediate Visiting Serere Ngora Kumi Bulambuli Kween Dr. -

Annual Report 2013-2014

ATOMIC ENERGY COUNCIL ANNUAL REPORT 2013/2014 JULY 1, 2013 - JUNE 30, 2014 “To regulate the peaceful applications and management of ionizing radiation for the protection and safety of society and the environment from the dangers resulting from ionizing radiation.” FOREWORD The Atomic Energy Council (AEC) is an Independent government regulatory body established by Atomic Energy Act, No. 24 of 2008, with a mandate to regulate the peaceful applications and management of ionizing radiation for the protection and safety of society and the environment from dangers resulting from ionizing radiation; to regulate the peaceful applications of ionizing radiation in the country. AEC has a number of regulatory functions which include among others; Development of Safety guides, Review & Assessment of documentation; Inspection and Enforcement, Registration, authorization and Licensing; Monitoring of occupationally exposed workers; Radioactive waste management; Environmental monitoring; Formation of a Radiological Emergency and Response Committee; Nuclear Security. Other than performing its regulatory functions, the Council made achievements which included; Establishment of cooperation with USNRC and TAEC, development of a strategic plan for Council, Radioactive contamination testing among others. The Council’s major constraint to the implementation of its regulatory functions is funding, coupled ZLWK LQDGHTXDWH HTXLSPHQW DQG LQVXIÀFLHQW QXPEHU RI DGPLQLVWUDWLYH DQG WHFKQLFDO VWDII7KH Council will focus onstrengthening its regulatory infrastructure, enhancing -

End-Of-Project Evaluation of the Ace Program

END-OF-PROJECT EVALUATION OF THE ACE PROGRAM FINAL EVALUATION REPORT September 2009 This document was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID/Uganda). It was prepared by The Mitchell Group, Inc. for the Uganda Monitoring and Evaluation Management Services, herein referred to as UMEMS, Contract Number 617-C-00-08-00012-00 END-OF-PROJECT EVALUATION OF THE ACE PROGRAM Prepared for United States Agency for International Development USAID/UGANDA Team Members: Jaime Benavente, Ph.D. Henry Emoi Gidudu, M.A. Nathan Nshakira, M.D. Hizaamu Ramadhan, MPH James Tapera, BSc, ACCA, ACPA. The Mitchell Group, Inc. 1816 11th Street N.W. Washington, D.C. 20001 DUNS#: 17528-5121 TIN#52-1467119 Telephone: (202) 745-1919 Facsimile: (202) 234-1697 Internet: the-mitchellgroup.com Kampala September, 2009 Executive Summary This report presents the findings, conclusions and recommendations of an external evaluation of Chemonics' AIDS Capacity Enhancement (ACE) project in Uganda. The USAID AIDS Capacity Enhancement (ACE) Project was a three-year project (2006-2008) that was granted a one-year extension (2008-2009) to build various capacities of selected Ugandan organizations and institutions, for improved and sustainable program outcomes in HIV/AIDS prevention, care, and treatment. The ACE project provided technical assistance, training, and material support (supplies and equipment) to two public institutions: the Uganda AIDS Commission (UAC) and the Ministry of Health Resource Center. In addition, it gave technical support to four HIV/AIDS service delivery non-governmental organizations (NGOs): the Inter-Religious Council of Uganda (IRCU) and its network of faith-based organizations, the Joint Clinical Research Center (JCRC), Hospice Africa-Uganda (HAU) and the Uganda Women’s Efforts to Save Orphans (UWESO). -

Health Sector Annual Budget Monitoring Report FY2019/20

Health SECtor ANNUAL BUDGET MONITORING REPORT FINANCIAL YEAR 2019/20 NOVEMBER 2020 Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development P.O. Box 8147, Kampala www.finance.go.ug Health Sector : Annual Budget Monitoring Report - FY 2019/20 A HEALTH SECtor ANNUAL BUDGET MONITORING REPORT FINANCIAL YEAR 2019/20 NOVEMBER 2020 Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ............................................................................................... iii FOREWORD ...................................................................................................................................... iv EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................... v CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Background .................................................................................................................................. 1 CHAPTER 2: METHODOLOGY ....................................................................................................... 2 2.1 Scope ....................................................................................................................................... 2 2.2 Methodology ................................................................................................................................ 3 2.2.1 Sampling ..................................................................................................................................... -

Workplace Stress Induced Among Nurses at Mbarara Regional

Nursi of ng al & rn C u a o r e J Journal of Nursing and Care Shiden et al., J Nurs Care 2017, 6:5 ISSN: 2167-1168 DOI: 10.4172/2167-1168.1000424 Research Article Open Access Workplace Stress Induced among Nurses at Mbarara Regional Referral Hospital, South West Uganda TOR Salome Shiden1*, Ndie Elkenah Chubike2 and Ofuti William2 1FCT Primary Health Care Board, Abuja Nigeria 2Department of Nursing Science, Ebonyi State University, Abakaliki, Nigeria 3Department of Nursing, Kampala International University,Isiaka Bushenyi Campus, South Western Uganda *Corresponding author: Shiden TOR, FCT Primary Health Board, Abuja Nigeria, Tel: 251468814986; E-mail: [email protected] Received date: August 01, 2017; Accepted date: August 24, 2017; Published date: September 02, 2017 Copyright: © 2017 Shiden TOR, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited Abstract This study aimed at assessing the factors contributing to stress in nurses’ workplace was conducted at Mbarara Regional Referral Hospital, South West Uganda. Random sampling method was used to select 50 nurses out of 180 that were on duty when data was collected. The data was collected using self-structured questionnaire. The results show that 25 (50%), said that their job condition is stressful, 5 (5%) said fair, 10% said they have a very poor job condition. 40% agreed that job promotion is done on merit, 20% of the respondents noted that promotion is done based on performance.