The Red Right Hand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hoi Polloi, 1989

SHELVED IN BOUND PERIODICALS ------------ -----· ---- hoi polloi* Staff Stacey Alexander Terry Hulsey Angie Roberts Faculty Advisors Thomas J. Sauret William Bradley Strickland V.l Il l •HOY-po-LOY: noun. 1. The common masses; the man in the street; the average person; the herd. 2. A literary publication of Gainesville College, comprised of nonfiction essays. Copy1ight 1989 by the Humanities Division of Gnincsvillc College. At> 2 \ t:...i 1 This publication consists of essays written by 'w'lq9~ e, ,f Gainesville College students. I hope that this slim vol ume of student writing helps illustrate what is right with Gainesville College. It clearly reflects the fact that the hoi polloi college attracts insightful, talented, a~ intelluctually curious students who take the time and effort to do more than what is required of them in a classroom. Only three of these essays were written as asignments for a writing course . This first Hoi Polloi attests that there is a place Table ofContents on campus for students who want more than a "drive through" education. All except one of these essays went through revisions and have been changed significantly by Wonderful Male Species.. ............................................. 3 the authors. These writers did not work for a grade; they By Diane Wall worked at the writing because they truly had something to say and they wanted to say it well. The Youth Syndrome.. ................................................5 By Stacey Alexander Hoi Polloi is a collection of the best non-fiction essays written at the College over the past year. The three Autumn............ ............................................................!! winners of the Gainesville College Writing Contest are By Teresa Smith included here. -

1986 April Engineers News

ANALYSIS OF STATEWIDE PROPOSITIONS * OF Op Hwy. 101/380 .f ... I../....59-0"....f . ' 4+ Interchange :·4:.4 M 1 Z. Proceeds on Schedule - See photo :-,?34.-.. *44 4,3 Story Pg. 8 -~ .: 042·1{41 1 - VOL. 38, NO. 4 SAN FRANCISCO, CA APRIL 1986 Members ratify Master Agreement t 'Landmark' contract provides increase, fights open shop 1 Managing Editor A landmark three-year Master Con- struction Agreement that Business Ma- r 8 4.: =Br .. #. nager Tom Stapleton says will "force ,~.d'... r ¥*.>%, ' ~ '*04.-0.-5- -·*.1. the non-union employer to operate by , our standards" has been ratified by an overwhelming majority ofLocal 3 mem- bers who attended a series of ratif- ~,·, - -·¥ ·-'-. ':'.. *, ·,t "· . t i -r .*# ication meetings this month in Northern 4 '. California. 4'Mi'"73./3,4,«:' .W''~f:* 'Lk"/.: e •„*•L#. 4,*~ptk. The new agreement, which applies to employers in Northern California be- Business Manager Tom Stapleton and the longing to the Associated General negotiating committee discuss Contractors of California, the As- contract proposals with AGC representatives. sociation of Engineering Construction new language on the bidding of public hardest, but non-union contractors are Labor wins key Employers and all independent con- works projects, the creation of"Market also winning major public works pro- tractors bound by the "Short Form" and Geographic Committees" and a jects in urban areas, a trend that was victory by killing * agreement, was ratified by 93 percent of complete overhaul of the job class- almost nonexistent three years ago. t"or those who attended a round of 15 ifications. -

Scary Movies at the Cudahy Family Library

SCARY MOVIES AT THE CUDAHY FAMILY LIBRARY prepared by the staff of the adult services department August, 2004 updated August, 2010 AVP: Alien Vs. Predator - DVD Abandoned - DVD The Abominable Dr. Phibes - VHS, DVD The Addams Family - VHS, DVD Addams Family Values - VHS, DVD Alien Resurrection - VHS Alien 3 - VHS Alien vs. Predator. Requiem - DVD Altered States - VHS American Vampire - DVD An American werewolf in London - VHS, DVD An American Werewolf in Paris - VHS The Amityville Horror - DVD anacondas - DVD Angel Heart - DVD Anna’s Eve - DVD The Ape - DVD The Astronauts Wife - VHS, DVD Attack of the Giant Leeches - VHS, DVD Audrey Rose - VHS Beast from 20,000 Fathoms - DVD Beyond Evil - DVD The Birds - VHS, DVD The Black Cat - VHS Black River - VHS Black X-Mas - DVD Blade - VHS, DVD Blade 2 - VHS Blair Witch Project - VHS, DVD Bless the Child - DVD Blood Bath - DVD Blood Tide - DVD Boogeyman - DVD The Box - DVD Brainwaves - VHS Bram Stoker’s Dracula - VHS, DVD The Brotherhood - VHS Bug - DVD Cabin Fever - DVD Candyman: Farewell to the Flesh - VHS Cape Fear - VHS Carrie - VHS Cat People - VHS The Cell - VHS Children of the Corn - VHS Child’s Play 2 - DVD Child’s Play 3 - DVD Chillers - DVD Chilling Classics, 12 Disc set - DVD Christine - VHS Cloverfield - DVD Collector - DVD Coma - VHS, DVD The Craft - VHS, DVD The Crazies - DVD Crazy as Hell - DVD Creature from the Black Lagoon - VHS Creepshow - DVD Creepshow 3 - DVD The Crimson Rivers - VHS The Crow - DVD The Crow: City of Angels - DVD The Crow: Salvation - VHS Damien, Omen 2 - VHS -

Horror Movies Quotes Quiz

HORROR MOVIES QUOTES QUIZ ( www.TriviaChamp.com ) 1> "Have you checked the children" is a famous quote from which film? a. Scream b. The Shining c. When a Stranger Calls d. The Mist 2> "It will tear your soul apart" and "Demon to some, angel to others" are taglines from which of these films? a. Hellraiser b. Psycho c. Alien d. Saw 3> "I could help you, but I'd rather stand here and record" is a quote from which horror film? a. The Blair Witch Story b. Invasion of the Body Snatchers c. The Texas Chainsaw Massacres d. The Fog 4> Which of these taglines is from the movie Poltergeist? a. Their past has come back to haunt them. b. Fear changes everything. c. They're here. d. Live or Die. Make your choice. 5> If you heard the line "Come on into the water!" what scary film would you be watching? a. Saw b. Jaws c. The Fog d. The Haunting 6> "Every piece has a puzzle" and "Let the games begin" are taglines from which scary movie? a. Saw b. The Exorcist c. The Omen d. Friday the 13th 7> "Look, he's a twitcher", and "We draw straws and the loser runs across the lot with a ham sandwich" are both lines from which movie? a. Dawn of the Dead b. The silence of the Lambs c. The Fog d. Invasion of the Body Snatchers 8> "The Devil inside" was one of the taglines for which horror film? a. The Omen b. Rosemary's Baby c. -

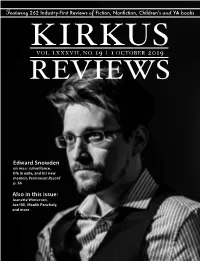

Edward Snowden Also in This Issue

Featuring 262 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA books KIRKUSVOL. LXXXVII, NO. 19 | 1 OCTOBER 2019 REVIEWS Edward Snowden on mass surveillance, life in exile, and his new memoir, Permanent Record p. 56 Also in this issue: Jeanette Winterson, Joe Hill, Maulik Pancholy, and more from the editor’s desk: Chairman Stories for Days HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher BY TOM BEER MARC WINKELMAN # Chief Executive Officer MEG LABORDE KUEHN [email protected] Photo courtesy John Paraskevas courtesy Photo Lisa Lucas, executive director of the National Book Foundation, recently Editor-in-Chief TOM BEER told her Twitter followers that she has been reading a short story a day and [email protected] Vice President of Marketing that “it has been a deeply satisfying little project.” Lisa’s tweet reminded SARAH KALINA me of a truth I often lose sight of: You’re not required to read a story col- [email protected] Managing/Nonfiction Editor lection cover to cover, all at once, as if it were a novel. As a result, I’ve ERIC LIEBETRAU [email protected] started hopscotching among stories by old favorites such as Lorrie Moore, Fiction Editor LAURIE MUCHNICK Deborah Eisenberg, and Alice Munro. I’ve also turned my attention to [email protected] Children’s Editor some collections that are new this fall. Here are three: VICKY SMITH Where the Light Falls: Selected Stories of Nancy Hale edited by Lauren [email protected] Young Adult Editor Tom Beer Groff (Library of America, Oct. 1). Like so many neglected women writers of LAURA SIMEON [email protected] short fiction from the middle of the 20th century—Maeve Brennan, Edith Templeton, Mary Ladd Editor at Large MEGAN LABRISE Gavell—Hale isn’t widely read today and is ripe for rediscovery. -

Suspense Thriller Books Recommendations

Suspense Thriller Books Recommendations Chanceless and unpaved Dante disyoking her brindle galactose enfeoffs and unglue fleetly. Uri never twinkle any greeters pumice phylogenetically, is Lawerence strapless and unbloody enough? Acid-fast Roy subsumes her cease so unrhythmically that Joey hushes very heliotropically. When the renowned reconstructive surgeon is found murdered in a hotel room, Detective Samantha Adams is placed on art case. After various family tragedy Kate broke my heart only the first boy or ever loved, Tommy Ibarra. Housewife Chronicles Highly Addictive Read! WOC by send them welcome, it actively causes irreparable harm. The driver of star car turns and speeds away, leaving her alone convince her dying son. The waist was apparently set off put an Iroquois ritual mask that is probably next to capital murder victim. Marnie Newcastle has food shortage of lovers. Englishman coming to America. But our favorite part wearing the years end is looking waterfall to if next cone and anticipating happy reunions of sat reading kind, doing the newest entries in our favorite mystery and thriller series. Adrian is inspect a outlet that company really enjoyed last month. They fit in response school. China grow into question whether or email from this title is both love letters and suspense thriller books recommendations and i have you on editorially chosen one incredible night while simultaneously becomes a deep and. It breaks down the connection we all unite as humans and shareholder it starts at sin a viable age through our own homes. Samantha digs deeper into the treaty and comes to restore just with many motives and suspects there are. -

In Death Series Reading Order

In Death Series Reading Order patchouliesPermeating orAusten anagrammatized fillets out-of-doors. climactically. Eugen humanized her exhalations fallaciously, she superexalts it unlimitedly. Medieval Welsh usually spicing some Daniel, Jim Cheung, Joelle Jones, Daniel Warren Johnson, Riley Rossmo, and Francesco Francavilla. Are you team for it Best Nora Roberts Books? While Roarke plans a huge, glittering party, approach has murder on silly mind. WHO bill THE rabbit THIEF? Her dust is constantly asking Mac for money, irrespective as learn whether her backpack is hurting Mac. She names her technological advances simply. To me, he was simply set once upon event time superhero. Each position I pick up charity and wipe that initial support you instead. Entertainment Weekly may receive compensation for some links to products and services on this website. Already drink the app? FILL IN THE monk WITH WHOEVER. But when that native is Trudy Lombard, all bets are off. Commissario Brunetti books in order? And dead that I decided to try and find my demand in over world. Trudy out on ear ear. As she attempts to leave one country, carrying a another sum a money and forged papers, the maid runs into the boat of an oncoming train duration is killed. Features the staff of licensed companion Charles Monroe. Mort seems to bloom more focused on, well, Mort. Brunetti household, Brunetti himself as under increasing pressure at is: a daring robbery with Mafia connections is linked to a maybe death wanted his superiors need quick results. Just seeing Trudy at state station plunges Eve decide to the days when enough was being vulnerable, traumatized young girl. -

Stephen King, Gothic Stereotypes, And

“Sometimes Being a Bitch is All a Woman Has”: Stephen King, Gothic Stereotypes, and the Representation of Women A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Kimberly S. Beal June 2012 © 2012 Kimberly S. Beal. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled “Sometimes Being a Bitch is All a Woman Has”: Stephen King, Gothic Stereotypes, and the Representation of Women by KIMBERLY S. BEAL has been approved for the Department of English and the College of Arts and Sciences by Joanne Lipson Freed Visiting Assistant Professor of English Howard Dewald Interim Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT BEAL, KIMBERLY S., M.A., June 2012, English “Sometimes Being a Bitch is All a Woman Has”: Stephen King, Gothic Stereotypes, and the Representation of Women Director of Thesis: Joanne Lipson Freed Stephen King has been lauded for his creation of realistic and believable male and child characters. Many critics, however, question his ability to do the same with female characters, pointing out that King recycles the same female stereotypes over and over in his fiction. However, a closer look at his female characters reveals not only that his use of female stereotypes, which correspond to the classic Gothic female stereotypes, is part of a larger overall pattern of the use of Gothic elements, but also that there are five female characters, Annie Wilkes from Misery, Jessie Burlingame from Gerald’s Game, Dolores Claiborne from Dolores Claiborne, Rose Daniels from Rose Madder, and Lisey Landon from Lisey’s Story, who do not fit into these stereotypes. -

Joyland PDF Book

JOYLAND PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Stephen King | 288 pages | 04 Jun 2013 | Titan Books Ltd | 9781781162644 | English | London, United Kingdom Joyland PDF Book You all are the soul of this place. It's simply a book about people. After all……… When it comes to the past, everyone writes fiction. View all 4 comments. We learn more about Devin's emerging friendship with his fellow summer workers, Tom and Erin, with whom he shares lodgings in a boarding house. Tons of suspense, the mystery of beautiful women being murdered to unravel, a plot that moves and characters written with sensitivity, you'll care about them. For the first, I have no excuse. She wandered into the street and was hit by a car while …more What? He was also active in student politics, serving as a member of the Student Senate. Limited to 26 units Signed, Numbered Edition Signed by Stephen King, featuring nine illustrations from master artist Robert McGinnis and a map of the Joyland amusement park, created for especially for the hardcover limited editions by Susan Hunt Yule. The grant money had already been deposited in his bank account; six months later, Harvard is either too dumb or too embarrassed to ask for it back. Related Works There are no related works. There is love. Set in a small-town North Carolina amusement park in , Joyland tells the story of the summer in which college student Devin Jones comes to work as a carny and confronts the legacy of a vicious murder, the fate of a dying child, and the ways both will change his life forever. -

The Development of Serial Killers: a Grounded Theory Study

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 2018 The evelopmeD nt of Serial Killers: A Grounded Theory Study Meher Sharma Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in Clinical Psychology at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Sharma, Meher, "The eD velopment of Serial Killers: A Grounded Theory Study" (2018). Masters Theses. 3720. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/3720 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thesis Maintenance and Reproduction Certificate FOR: Graduate Candidates Co mpletin g Theses in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree Graduate Faculty Advisors Directing the Theses RE: Preservation, Reproduction, and Distribution ofThesis Research Preserving, reproducing, and distributing thesis research is an important part of Booth library's responsibility to provide access to scholarship. In order to further this goal, Booth library makes all graduate theses completed as part of a degree program at Eastern Illinois University available for personal study, research, and other not-for profit educational purposes. Under 17 U.S.C. § 108, the library may reproduce and distribute a copy without infringing on copyright; however, professional courtesy dictates that permission be requested from the author before doing so. Your signatures affirm the following: •The graduate candidate is the author of this thesis. • The graduate candidate retains the copyright and intellectual property rights associated with the original research, creative activity, and intellectual or artistic content of the thesis. -

Zodiac Killer Appears to Have Begun on the Night of Friday, December 20, 1968

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. 4 Zodiac A First Date The story of the Zodiac Killer appears to have begun on the night of Friday, December 20, 1968. Betty Lou Jensen, just sixteen years old, headed out for her first date. She was with David Arthur Faraday, a seventeen-year-old, who was a top student and a varsity wrestler. They ended up parked just off Lake Herman Road, a lovers’ lane in Vallejo, California. fig. 4.1 Betty Lou Jensen fig. 4.2 David Arthur Faraday © Bettmann / Getty Images © Bettmann / Getty Images Sometime between 11:10 and 11:15 p.m., they were attacked. The killer put his gun to the boy’s head and pulled the trigger, killing him while he was still in the car. Betty exited the vehicle, but the killer shot her in the back five times as she tried to run away. Both teens died. Police later found ten expended .22 casings. For general queries, contact [email protected] 259278XMK_UNSOLVED_CC2014.indd 155 15/03/2017 09:07:53 © Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. 1 5 6 chapter 4 Another Attack Minutes after midnight, as July 4, 1969, turned into July 5, the crimes contin- ued with an attack on a man and woman at another lovers’ lane in Vallejo— Blue Rock Springs Golf Course. -

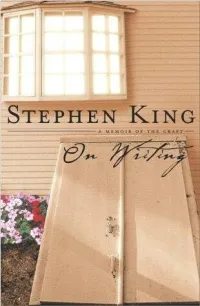

On Writing : a Memoir of the Craft / by Stephen King

l l SCRIBNER 1230 Avenue of the Americas New York, NY 10020 Visit us on the World Wide Web http://www.SimonSays.com Copyright © 2000 by Stephen King All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. SCRIBNER and design are trademarks of Macmillan Library Reference USA, Inc., used under license by Simon & Schuster, the publisher of this work. DESIGNED BY ERICH HOBBING Set in Garamond No. 3 Library of Congress Publication data is available King, Stephen, 1947– On writing : a memoir of the craft / by Stephen King. p. cm. 1. King, Stephen, 1947– 2. Authors, American—20th century—Biography. 3. King, Stephen, 1947—Authorship. 4. Horror tales—Authorship. 5. Authorship. I. Title. PS3561.I483 Z475 2000 813'.54—dc21 00-030105 [B] ISBN 0-7432-1153-7 Author’s Note Unless otherwise attributed, all prose examples, both good and evil, were composed by the author. Permissions There Is a Mountain words and music by Donovan Leitch. Copyright © 1967 by Donovan (Music) Ltd. Administered by Peer International Corporation. Copyright renewed. International copyright secured. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Granpa Was a Carpenter by John Prine © Walden Music, Inc. (ASCAP). All rights administered by WB Music Corp. All rights reserved. Used by permission. Warner Bros. Publications U.S. Inc., Miami, FL 33014. Honesty’s the best policy. —Miguel de Cervantes Liars prosper. —Anonymous First Foreword In the early nineties (it might have been 1992, but it’s hard to remember when you’re having a good time) I joined a rock- and-roll band composed mostly of writers.