Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VORTEX Playing Mrs Constance Clarke

THE BIG FINISH MAGAZINE MARCH 2021 MARCH ISSUE 145 DOCTOR WHO: DALEK UNIVERSE THE TENTH DOCTOR IS BACK IN A BRAND NEW SERIES OF ADVENTURES… ALSO INSIDE TARA-RA BOOM-DE-AY! WWW.BIGFINISH.COM @BIGFINISH THEBIGFINISH @BIGFINISHPROD BIGFINISHPROD BIG-FINISH WE MAKE GREAT FULL-CAST AUDIO DRAMAS AND AUDIOBOOKS THAT ARE AVAILABLE TO BUY ON CD AND/OR DOWNLOAD WE LOVE STORIES Our audio productions are based on much-loved TV series like Doctor Who, Torchwood, Dark Shadows, Blake’s 7, The Avengers, The Prisoner, The Omega Factor, Terrahawks, Captain Scarlet, Space: 1999 and Survivors, as well as classics such as HG Wells, Shakespeare, Sherlock Holmes, The Phantom of the Opera and Dorian Gray. We also produce original creations such as Graceless, Charlotte Pollard and The Adventures of Bernice Summerfield, plus the THE BIG FINISH APP Big Finish Originals range featuring seven great new series: The majority of Big Finish releases ATA Girl, Cicero, Jeremiah Bourne in Time, Shilling & Sixpence can be accessed on-the-go via Investigate, Blind Terror, Transference and The Human Frontier. the Big Finish App, available for both Apple and Android devices. Secure online ordering and details of all our products can be found at: bgfn.sh/aboutBF EDITORIAL SINCE DOCTOR Who returned to our screens we’ve met many new companions, joining the rollercoaster ride that is life in the TARDIS. We all have our favourites but THE SIXTH DOCTOR ADVENTURES I’ve always been a huge fan of Rory Williams. He’s the most down-to-earth person we’ve met – a nurse in his day job – who gets dragged into the Doctor’s world THE ELEVEN through his relationship with Amelia Pond. -

Bloodsuckers Doom Coalition Finished Picture Plus!

WWW.BIGFINISH.COM • NEW AUDIO ADVENTURES ISSUE 92 • OCTOBER 2016 CELEBRATING 10 YEARS OF CARDIFF'S FINEST! PLUS! JAGO & LITEFOOT! DOCTOR WHO! DORIAN GRAY! BLOODSUCKERS DOOM COALITION FINISHED PICTURE A BARMAID GOES BAD! THIRD SERIES OVERVIEW! FINAL SERIES PREVIEW! HEADING WELCOME TO BIG FINISH! We love stories and we make great full-cast audio dramas and audiobooks you can buy on CD and/or download Big Finish… Subscribers get more We love stories! at bigfinish.com! Our audio productions are based on much- If you subscribe, depending on the range you loved TV series like Doctor Who, Torchwood, subscribe to, you get free audiobooks, PDFs Dark Shadows, Blake's 7, The Avengers and of scripts, extra behind-the-scenes material, a Survivors as well as classic characters such as bonus release, downloadable audio readings of Sherlock Holmes, The Phantom of the Opera new short stories and discounts. and Dorian Gray, plus original creations such as Graceless, Charlotte Pollard and The You can access a video guide to the site at Adventures of Bernice Summerfield. www.bigfinish.com/news/v/website-guide-1 WWW.BIGFINISH.COM @ BIGFINISH THEBIGFINISH WELCOME TO VORTEX EDITORIAL SNEAK PREVIEW COLD FUSION OOM COALITION is a very clever thing. Each story needs to be able to stand on its D own, as a piece of entertaining drama. But the four stories in each box set need to unify to tell a bigger story, which feels complete in its own right. But then, the four box sets need to work together, to relate a full adventure in 16 parts. -

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS in SCIENCE FICTION and FANTASY (A Series Edited by Donald E

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS IN SCIENCE FICTION AND FANTASY (a series edited by Donald E. Palumbo and C.W. Sullivan III) 1 Worlds Apart? Dualism and Transgression in Contemporary Female Dystopias (Dunja M. Mohr, 2005) 2 Tolkien and Shakespeare: Essays on Shared Themes and Language (ed. Janet Brennan Croft, 2007) 3 Culture, Identities and Technology in the Star Wars Films: Essays on the Two Trilogies (ed. Carl Silvio, Tony M. Vinci, 2007) 4 The Influence of Star Trek on Television, Film and Culture (ed. Lincoln Geraghty, 2008) 5 Hugo Gernsback and the Century of Science Fiction (Gary Westfahl, 2007) 6 One Earth, One People: The Mythopoeic Fantasy Series of Ursula K. Le Guin, Lloyd Alexander, Madeleine L’Engle and Orson Scott Card (Marek Oziewicz, 2008) 7 The Evolution of Tolkien’s Mythology: A Study of the History of Middle-earth (Elizabeth A. Whittingham, 2008) 8 H. Beam Piper: A Biography (John F. Carr, 2008) 9 Dreams and Nightmares: Science and Technology in Myth and Fiction (Mordecai Roshwald, 2008) 10 Lilith in a New Light: Essays on the George MacDonald Fantasy Novel (ed. Lucas H. Harriman, 2008) 11 Feminist Narrative and the Supernatural: The Function of Fantastic Devices in Seven Recent Novels (Katherine J. Weese, 2008) 12 The Science of Fiction and the Fiction of Science: Collected Essays on SF Storytelling and the Gnostic Imagination (Frank McConnell, ed. Gary Westfahl, 2009) 13 Kim Stanley Robinson Maps the Unimaginable: Critical Essays (ed. William J. Burling, 2009) 14 The Inter-Galactic Playground: A Critical Study of Children’s and Teens’ Science Fiction (Farah Mendlesohn, 2009) 15 Science Fiction from Québec: A Postcolonial Study (Amy J. -

1 2019 Gally Academic Track Friday, February 15

2019 Gally Academic Track Friday, February 15, 2019 3:00-3:15 KEYNOTE “The Fandom Hierarchy: Women of Color’s Fight For Visibility In Fandom Spaces” Tai Gooden Women of Color (WoC) have been fervent Doctor Who fans for several decades. However, the fandom often reflects societal hierarchies upheld by White privilege that result in ignoring and diminishing WoC’s opinions, contributions, and legitimate concerns about issues in terms of representation. Additionally, WoC and non-binary (NB) people of color’s voices are not centered as often in journalism, podcasting, and media formats nor convention panels as much as their White counterparts. This noticeable disparity has led to many WoC, even those who are deemed “important” in fandom spaces, to encounter racism, sexism, and, depending on the individual, homophobia and transphobia in a place that is supposed to have open availability to everyone. I can attest to this experience as someone who has a somewhat heightened level of visibility in fandom as a pop culture/entertainment writer who extensively covers Doctor Who. This presentation will examine women of color in the Doctor Who fandom in terms of their interactions with non-POC fans and difficulties obtaining opportunities in media, online, and at conventions. The show’s representation of fandom and the necessity for equity versus equality will also be discussed to craft a better understanding of how to tackle this pervasive issue. Other actionable solutions to encourage intersectionality in the fandom will be discussed including privileged people listening to WoC and non- binary people’s concerns/suggestions, respectfully interacting with them online and in person, recognizing and utilizing their privilege to encourage more inclusivity, standing in solidarity with them on critical issues, and lending their support to WoC creatives. -

King and Country: Shakespeare’S Great Cycle of Kings Richard II • Henry IV Part I Henry IV Part II • Henry V Royal Shakespeare Company

2016 BAM Winter/Spring #KingandCountry Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board BAM, the Royal Shakespeare Company, and Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board The Ohio State University present Katy Clark, President Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer King and Country: Shakespeare’s Great Cycle of Kings Richard II • Henry IV Part I Henry IV Part II • Henry V Royal Shakespeare Company BAM Harvey Theater Mar 24—May 1 Season Sponsor: Directed by Gregory Doran Set design by Stephen Brimson Lewis Global Tour Premier Partner Lighting design by Tim Mitchell Music by Paul Englishby Leadership support for King and Country Sound design by Martin Slavin provided by the Jerome L. Greene Foundation. Movement by Michael Ashcroft Fights by Terry King Major support for Henry V provided by Mark Pigott KBE. Major support provided by Alan Jones & Ashley Garrett; Frederick Iseman; Katheryn C. Patterson & Thomas L. Kempner Jr.; and Jewish Communal Fund. Additional support provided by Mercedes T. Bass; and Robert & Teresa Lindsay. #KingandCountry Royal Shakespeare Company King and Country: Shakespeare’s Great Cycle of Kings BAM Harvey Theater RICHARD II—Mar 24, Apr 1, 5, 8, 12, 14, 19, 26 & 29 at 7:30pm; Apr 17 at 3pm HENRY IV PART I—Mar 26, Apr 6, 15 & 20 at 7:30pm; Apr 2, 9, 23, 27 & 30 at 2pm HENRY IV PART II—Mar 28, Apr 2, 7, 9, 21, 23, 27 & 30 at 7:30pm; Apr 16 at 2pm HENRY V—Mar 31, Apr 13, 16, 22 & 28 at 7:30pm; Apr 3, 10, 24 & May 1 at 3pm ADDITIONAL CREATIVE TEAM Company Voice -

Gender Equity Through Gender Teaching Online

Proceedings of the 4th International Barcelona Conference on Higher Education Vol. 3. Higher education and gender equity GUNI - Global University Network for Innovation – www.guni- rmies.net Gender equity through gender teaching online Olena Goroshko Head of Cross-Cultural and Business Communication Department National Technical University “Kharkiv Polytechnic Institute” Ukraine Quotation information GOROSHKO, Olena (2008), “Gender equity through gender teaching online”. Proceedings of the 4th International Barcelona Conference on Higher Education, Vol. 3. Higher education and gender equity. Barcelona: GUNI. Available at http://www.guni- rmies.net. Abstract Gender equity in higher education is more than putting women on equal footing with men. It is eliminating barriers to participation and stereotypes that limit the opportunities and choices for both sexes. Gender equity is about enriching classrooms, widening opportunities, and expanding choices for all students. And I consider that this supposition can be applied not only to the education but all rhetoric of everyday life. Thus, the goal of gender education is not only to provide students with proper knowledge, but deconstruct stereotypes in their thinking and behaviour. Hence, all courses about gender issues must be based on the principle “explain to me – and I will forget; show me - and I will remember; let me participate – and I will understand”. The teaching methodology in subject-orientated (gender) class first of all must be targeted at active student-centered learning (learning by doing and changing by learning) (Gritzenko, 2003). In Ukraine, the issue of getting closer to the international higher educational standards was raised in the late 1990s. It related not only to the courses’ content, curricula and syllabi’s renewal, but transforming national universities as social institutes on the whole. -

See What's on ¶O – Lelo This Week, This Hour, This Second

FOR THE WEEK OF MAY 28 - JUNE 3, 2017 THE GREAT INDEX TO FUN DINING • ARTS • MUSIC • NIGHTLIFE Look for it every Friday in the HIGHLIGHTS THIS WEEK on Fox. Jamie Foxx hosts this new game show, which TODAY TUESDAY features Shazam, the world’s most popular song identi- The Leftovers World of Dance fication app. HBO 6:00 p.m. KHNL 9:00 p.m. FRIDAY Kevin (Justin Theroux) assumes an alternate identity Extraordinary dancers from all ages and walks of life Shark Tank when he embarks on a mission of mercy in a new epi- kick off the qualifier round for the chance to win a life- sode of “The Leftovers,” airing today on HBO. altering $1-million prize in the premiere of “World of KITV 7:00 p.m. The post-apocalyptic drama follows a family of survi- Dance,” airing Tuesday on NBC. Jenna Dewan Tatum vors a few years after the mysterious simultaneous dis- serves as mentor and host, while Jennifer Lopez, Business moguls decide whether or not to invest appearance of 140 million people. Derek Hough and Ne-Yo serve as judges. their own money in new products and companies in back-to-back episodes of the critically acclaimed reali- ty TV series “Shark Tank,” airing Friday on ABC. MONDAY WEDNESDAY Hopeful entrepreneurs pitch their ideas in the hopes of Lucifer The F Word snagging a deal with a Shark. KHON 8:00 p.m. KHON 8:00 p.m. SATURDAY Charlotte (Tricia Helfer) acciden- Celebrity chef and TV personality Gordon Ram- To Tell the Truth tally charbroils a man to death say hosts as foodie families and friends compete in self-defence, and Lucifer in high-stakes cook-offs in “The F Word,” pre- KITV 7:00 p.m. -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

National Security and Local Police

BRENNAN CENTER FOR JUSTICE NATIONAL SECURITY AND LOCAL POLICE Michael Price Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law ABOUT THE BRENNAN CENTER FOR JUSTICE The Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law is a nonpartisan law and policy institute that seeks to improve our systems of democracy and justice. We work to hold our political institutions and laws accountable to the twin American ideals of democracy and equal justice for all. The Center’s work ranges from voting rights to campaign finance reform, from racial justice in criminal law to Constitutional protection in the fight against terrorism. A singular institution — part think tank, part public interest law firm, part advocacy group, part communications hub — the Brennan Center seeks meaningful, measurable change in the systems by which our nation is governed. ABOUT THE BRENNAN CENTER’S LIBERTY AND NATIONAL SECURITY PROGRAM The Brennan Center’s Liberty and National Security Program works to advance effective national security policies that respect Constitutional values and the rule of law, using innovative policy recommendations, litigation, and public advocacy. The program focuses on government transparency and accountability; domestic counterterrorism policies and their effects on privacy and First Amendment freedoms; detainee policy, including the detention, interrogation, and trial of terrorist suspects; and the need to safeguard our system of checks and balances. ABOUT THE BRENNAN CENTER’S PUBLICATIONS Red cover | Research reports offer in-depth empirical findings. Blue cover | Policy proposals offer innovative, concrete reform solutions. White cover | White papers offer a compelling analysis of a pressing legal or policy issue. -

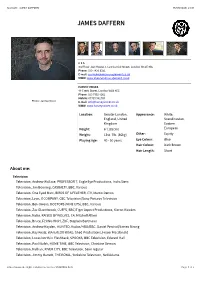

James Daffern 15/09/2020, 21�09

Spotlight: JAMES DAFFERN 15/09/2020, 2109 JAMES DAFFERN C S A 3rd Floor Joel House, 17-21 Garrick Street, London WC2E 9BL Phone: 020-7420 9351 E-mail: [email protected] WWW: www.shepherdmanagement.co.uk HARVEY VOICES 49 Greek Street, London W1D 4EG Phone: 020 7952 4361 Mobile: 07739 902784 Photo: Jennie Scott E-mail: [email protected] WWW: www.harveyvoices.co.uk Location: Greater London, Appearance: White, England, United Scandinavian, Kingdom Eastern Height: 6' (182cm) European Weight: 13st. 7lb. (86kg) Other: Equity Playing Age: 40 - 50 years Eye Colour: Blue Hair Colour: Dark Brown Hair Length: Short About me: Television Television, Andrew Wallace, PROFESSOR T, Eagle Eye Productions, Indra Siera Television, Jim Bonning, CASUALTY, BBC, Various Television, One Eyed Marc, BIRDS OF A FEATHER, ITV, Martin Dennis Television, Leon, X COMPANY, CBC Television/Sony Pictures Television Television, Ben Owens, DOCTORS (NINE EPS), BBC, Various Television, Zac Glazerbrook, CUFFS, BBC/Tiger Aspect Productions, Kieron Hawkes Television, Natie, RAISED BY WOLVES, C4, Mitchell Altieri Television, Bruce, FLYING HIGH, ZDF, Stephen Bartmann Television, Andrew Hayden, HUNTED, Kudos/HBO/BBC, Daniel Percival/James Strong Television, Ray Keats, WATERLOO ROAD, Shed Productions, Fraser Macdonald Television, Lucas North in Flashback, SPOOKS, BBC Television, Edward Hall Television, Paul Walsh, HOME TIME, BBC Television, Christine Gernon Television, Nathan, RIVER CITY, BBC Television, Semi regular Television, Jimmy Barrett, THE ROYAL, Yorkshire Television, -

A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM of DOCTOR WHO Noah Zepponi University of the Pacific, [email protected]

University of the Pacific Scholarly Commons University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2018 THE DOCTOR OF CHANGE: A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM OF DOCTOR WHO Noah Zepponi University of the Pacific, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uop_etds Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Zepponi, Noah. (2018). THE DOCTOR OF CHANGE: A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM OF DOCTOR WHO. University of the Pacific, Thesis. https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uop_etds/2988 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 2 THE DOCTOR OF CHANGE: A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM OF DOCTOR WHO by Noah B. Zepponi A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS College of the Pacific Communication University of the Pacific Stockton, California 2018 3 THE DOCTOR OF CHANGE: A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM OF DOCTOR WHO by Noah B. Zepponi APPROVED BY: Thesis Advisor: Marlin Bates, Ph.D. Committee Member: Teresa Bergman, Ph.D. Committee Member: Paul Turpin, Ph.D. Department Chair: Paul Turpin, Ph.D. Dean of Graduate School: Thomas Naehr, Ph.D. 4 DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my father, Michael Zepponi. 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is here that I would like to give thanks to the people which helped me along the way to completing my thesis. First and foremost, Dr. -

Stream Name Category Name Coronavirus (COVID-19) |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---TNT-SAT ---|EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 SD |EU|

stream_name category_name Coronavirus (COVID-19) |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---------- TNT-SAT ---------- |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 FULL HD 1 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 FHD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT PARIS PREMIERE |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT PARIS PREMIERE FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC 1 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ARTE SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ARTE FR |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT RMC STORY |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT RMC STORY SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---------- Information ---------- |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TV5 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TV5 MONDE FBS HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT France 24 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE INFO SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE INFO HD