Scholarship @ Claremont

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Appellate Jurisdiction) IA No.231 Of

I.A. No.231 of 2012 in DFR No.1092 of 2012 Appellate Tribunal for Electricity (Appellate Jurisdiction) I.A. No.231 of 2012 IN DFR No.1092 of 2012 Dated: 20th July, 2012 Present : HON’BLE MR. JUSTICE M KARPAGA VINAYAGAM, CHAIRPERSON HON’BLE MR. RAKESH NATH, TECHNICAL MEMBER In the Matter of: Indian Oil Corporation Ltd. Pipelines Division A-1, Udyog Marg, Sector-1 NOIDA -201 301(U.P) …Appellant/Applicant Versus 1. Gujarat Electricity Regulatory Commission(GERC) 1ST Floor, Neptune Tower Ashram Road, Ahemedabad-380009. 2. Paschim Gujarat Vij Company Ltd., (PGVCL) Registered and Corporate Office at Laxim Nagar, Nana Mava Main Road Rajkot Gujarat – 360 004 Page 1 of 6 I.A. No.231 of 2012 in DFR No.1092 of 2012 3. Uttar Gujarat Vij Company Ltd., (UGVCL), Registerd and Corporate office at Visnagar Road Mehasana – 384 001 4. Gujarat Energy Transmission Corporation Ltd., (GETCO) Corporate office at Sardar Patel Vidyut Bhawan Race Course Vadodara – 390 007 ...Respondent(s) Counsel for the Appellant(s) : Mr. V.N. Koura Ms. Mona Aneja Counsel for the Respondent(s):- O R D E R PER HON’BLE MR. JUSTICE M. KARPAGA VINAYAGAM, CHAIRPERSON 1. This is an Application filed by the Appellant/Applicant to condone the delay of 715 days in filing the Appeal as against the impugned order dated 13.5.2010. 2. The explanation of this huge delay has been given by the Applicant/Appellant, which is follows:- Page 2 of 6 I.A. No.231 of 2012 in DFR No.1092 of 2012 “ (a) The Applicant filed the Petition No.1004 of 2010 praying for direction to the Distribution Licensee Respondents to pay the applicable tariff to the Applicant as determined by the State Commission. -

Internal Audit

Annexure-1 Oraganisations who recognised CMAs for Internal Audit/Concurrent Audit S.No. Name of Organisations Central PSU 1 Airports Authority of India 2 Andaman and Nicobar Islands Integrated Development Corporation Limited 3 Andrew Yule & Company Limited 4 Artificial Limbs Manufacturing Corporation of India Limited 5 Biecco Lawrie Limited 6 Bharat Coking Coal Limited 7 Bharat Heavy Electricals Limited 8 Bharat Wagon Engineering Co. Ltd 9 BharatBroadband Network Limited 10 Bharat Sanchar Nigam Limited 11 Brahmaputra Valley Fertilizer Corporation Limited 12 Braithwaite & Co. Limited 13 Bharat Dynamic Limited 14 Burn Standard Co. Ltd 15 Central Cottage Industries of India Ltd. 16 Central Coalfields Limited 17 Central Electronics Limited 18 Central Mine Planning & Design Institute Limited 19 CENTRAL COTTAGE INDUSTRIES CORPORATION OF INDIA LIMITED 20 Coal India Limited 21 Container Corporation of India 22 Dedicated Freight Corridor Corporation of India Limited 23 Durgapur Chemicals Limited 24 Eastern Coalfields Limited 25 Fertilisers and Chemicals Travancore Limited (FACT Ltd.) 26 Ferro Scrap Nigam Ltd 27 Garden Reach Shipbuliders & Engineers Limited 28 GOA SHIPYARD LIMITED 29 Heavy Engineering Corporation Limited 30 Hindustan Aeronautics Limited 31 HIL (INDIA) LIMITED formerly known as Hindustan Insecticides Limited 32 Hindustan Newsprint Limited 33 Handicrafts & Handlooms Exports Corporations of India Ltd. 34 HLL Lifecare Ltd 34 HMT Ltd. 35 HMT MACHINE TOOLS LIMITED 36 IFCI Infrastructure Development Limited India-Infrastructure-Finance-Company-Limited -

Addedndum to Petition 1914.Pdf

BEFORE THE GUJARAT ELECTRICITY REGULATORY COMMISSION GANDHINAGAR CASE NO. 1914/2020 Determination of Aggregate Revenue Requirement And Tariff of FY 2021-22 Under GERC (Multi Year Tariff) Regulations, 2016 along with other Guidelines and Directions issued by the GERC from time to time AND under Part VII (Section 61 to Section 64) of the Electricity Act, 2003 read with the relevant Guidelines Filed by:- Paschim Gujarat Vij Company Ltd. Corp. Office: Paschim Gujarat Vij Seva Sadan, Off. Nana Mava Main Road, Laxminagar, Rajkot– 360004. Determination of ARR & Tariff for FY 2021-22 BEFORE THE GUJARAT ELECTRICITY REGULATORY COMMISSION GANDHINAGAR Filing No: Case No: 1914/2020 IN THE MATTER OF Filing of the Petition for determination of ARR & Tariff for FY 2021-22, under GERC (Multi Year Tariff) Regulations, 2016 along with other Guidelines and Directions` issued by the GERC from time to time AND under Part VII (Section 61 to Section 64) of the Electricity Act, 2003 read with the relevant Guidelines AND IN THE MATTER OF Paschim Gujarat Vij Company Limited, Paschim Gujarat Vij Seva Sadan, Off. Nana Mava Main Road, Laxminagar, Rajkot – 360004. PETITIONER Gujarat Urja Vikas Nigam Limited Sardar Patel Vidyut Bhavan, Race Course, Vadodara - 390 007 CO-PETITIONER THE PETITIONER ABOVE NAMED RESPECTFULLY SUBMITS Paschim Gujarat Vij Company Limited 63 Determination of ARR & Tariff for FY 2021-22 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION 1. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................... 68 1.1. PREAMBLE ............................................................................................................ -

Merchants Where Online Debit Card Transactions Can Be Done Using ATM/Debit Card PIN Amazon IRCTC Makemytrip Vodafone Airtel Tata

Merchants where online Debit Card Transactions can be done using ATM/Debit Card PIN Amazon IRCTC Makemytrip Vodafone Airtel Tata Sky Bookmyshow Flipkart Snapdeal icicipruterm Odisha tax Vodafone Bharat Sanchar Nigam Air India Aircel Akbar online Cleartrip Cox and Kings Ezeego one Flipkart Idea cellular MSEDC Ltd M T N L Reliance Tata Docomo Spicejet Airlines Indigo Airlines Adler Tours And Safaris P twentyfourBySevenBooking Abercrombie n Kent India Adani Gas Ltd Aegon Religare Life Insur Apollo General Insurance Aviva Life Insurance Axis Mutual Fund Bajaj Allianz General Ins Bajaj Allianz Life Insura mobik wik Bangalore electricity sup Bharti axa general insura Bharti axa life insurance Bharti axa mutual fund Big tv realiance Croma Birla sunlife mutual fund BNP paribas mutural fund BSES rajdhani power ltd BSES yamuna power ltd Bharat matrimoni Freecharge Hathway private ltd Relinace Citrus payment services l Sistema shyam teleservice Uninor ltd Virgin mobile Chennai metro GSRTC Club mahindra holidays Jet Airways Reliance Mutual Fund India Transact Canara HSBC OBC Life Insu CIGNA TTK Health Insuranc DLF Pramerica Life Insura Edelweiss Tokio Life Insu HDFC General Insurance IDBI Federal Life Insuran IFFCO Tokio General Insur India first life insuranc ING Vysya Life Insurance Kotak Mahindra Old Mutual L and T General Insurance Max Bupa Health Insurance Max Life Insurance PNB Metlife Life Insuranc Reliance Life Insurance Royal Sundaram General In SBI Life Insurance Star Union Daiichi Life TATA AIG general insuranc Universal Sompo General I -

Financial Statements of the Compau:, for the Year Ended March 3 I

adani Renewables August 04, 2021 BSE Limited National Stock Exchange of India Limited P J Towers, Exchange plaza, Dalal Street, Bandra-Kurla Complex, Bandra (E) Mumbai – 400001 Mumbai – 400051 Scrip Code: 541450 Scrip Code: ADANIGREEN Dear Sir, Sub: Outcome of Board Meeting held on August 04, 2021 With reference to above, we hereby submit / inform that: 1. The Board of Directors (“the Board”) at its meeting held on August 04, 2021, commenced at 12.00 noon and concluded at 1.20 p.m., has approved and taken on record the Unaudited Financial Results (Standalone and Consolidated) of the Company for the Quarter ended June 30, 2021. 2. The Unaudited Financial Results (Standalone and Consolidated) of the Company for the Quarter ended June 30, 2021 prepared in terms of Regulation 33 of the SEBI (Listing Obligations and Disclosures Requirements) Regulations, 2015 together with the Limited Review Report of the Statutory Auditors are enclosed herewith. The results are also being uploaded on the Company’s website at www.adanigreenenergy.com. The presentation on operational & financial highlights for the quarter ended June 30, 2021 is enclosed herewith and also being uploaded on our website. 3. Press Release dated August 04, 2021 on the Unaudited Financial Results of the Company for the Quarter ended June 30, 2021 is enclosed herewith. Adani Green Energy Limited Tel +91 79 2555 5555 “Adani Corporate House”, Shantigram, Fax +91 79 2555 5500 Nr. Vaishno Devi Circle, S G Highway, [email protected] Khodiyar, www.adanigreenenergy.com Ahmedabad – 382 421 Gujarat, India CIN: L40106GJ2015PLC082007 Registered Office: “Adani Corporate House”, Shantigram, Nr. -

Before the Gujarat Electricity Regulatory Commission

BEFORE THE GUJARAT ELECTRICITY REGULATORY COMMISSION GANDHINAGAR Petition No 1712 of 2018 In the matter of: Petition under the provision of Electricity Act, 2003 read with GERC (Terms and Conditions of Intra- State Open Access) Regulations, 2011 and in the matter of seeking refund of amount of transmission wheeling charges paid by the Petitioner company Under Protest and in the matter of decision/ order dated 10.05.2017 passed by the Respondent authority rejecting the request/application of refund of amount paid towards Exit Option Charge for Wind Mill No. ADO-36 made by the Petitioner company. Petitioner: Gokul Refoils and Solvent, Gokul House, 43, Shreemali Co-Operative Housing Soc. Ltd., Opp. Shikhar Building, Navrangpura, Ahmedabad. Co-Petitioner: Gokul Agri International Ltd, State Highway No. 41, Near Sujanpur Patia, Sidhpur, District: Patan, Pin Code – 384151 Represented by: Learned Advocate Shri Satyan Thakkar and Shri Nisarg Rawal V/s. Respondent: Gujarat Energy Transmission Corporation Ltd. Sardar Patel Vidyut Bhavan, Race Course, Vadodara- 390 007. Represented by: Learned Sernior Advocate Shri M. G. Ramchandran with Advocate Ms. Ranjitha Ramchandran and Ms. Venu Birappa CORAM: Shri Anand Kumar, Chairman Shri P. J. Thakkar, Member Date: 09/03/2020 ORDER 1 1 The present petition has been filed by M/s Gokul Refoils & Solvent Limited and M/s Gokul Agri International Limited seeking following prayer: “The Commission may be pleased to quash and set aside the impugned decision/order dated 10.05.2017 passed by the Additional Engineer (R&C), Gujarat Energy Transmission Corporation Limited and further be pleased to direct the Gujarat Energy Transmission Corporation Limited i.e. -

Creating Sustainable Surat* Climate Change Plan Surat Agenda Topics of Discussion

Surat Municipal Corporation The Southern Gujarat Chamber of Commerce & Namaste ! Industry *Creating sustainable Surat* Climate Change Plan Surat Agenda Topics of Discussion About Surat Results to-date ~ Climate Hazards ~ Apparent Areas of Climate Vulnerability and Likely Future Issues Activities and Methods ~ Work Plan ~ Organizations Involved ~ CAC Arrangement ~ Activities undertaken so far ~ Methods Used for Analysis Sectoral Studies Pilot Projects Challenges and Questions Next Steps Glory of Surat Historical Centre for Trade & Commerce English, Dutch, Armenian & Moguls Settled Leading City of Gujarat 9th Largest City of India Home to Textile and Diamond Industries 60% of Nation’s Man Made Fabric Production 600,000 Power Looms and 450 Process Houses Traditional Zari and Zardosi Work 70% of World’s Diamond Cutting and Polishing Spin-offs from Hazira, Largest Industrial Hub Peace-loving, Resilient and Harmonious Environment Growth of Surat Year 1951 Area 1961 Sq. in Km 1971 8.18 223,182 Population 1981 8.18 288,026 1991 33.85 471,656 2001 55.56 776,583 2001* 111.16 1,498,817 2009 112.27 2,433,785 326.51 2,877,241 Decline of Emergence of 326.51 ~ Trade Centre Development mercantile of Zari, silk & Diamond, Chief port of of British India – Continues to trade – regional other small Textiles & Mughal Empire trade centre other mfg. 4 be major port and medium million industries Medieval Times 1760- late 1800s 1900 to 1950s 1950s to 1980s 1980s onwards Emergence of Petrochemicals -Re-emergence Consolidation as major port, of -

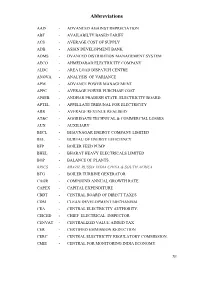

09 List of Abbreviations.Pdf

Abbreviations AAD - ADVANCED AGAINST DEPRECIATION ABT - AVAILABILTY BASED TARIFF ACS - AVERAGE COST OF SUPPLY ADB - ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK ADMS - DVANCED DISTRIBITION MANAGEMENT SYSTEM AECO - AHMEDABAD ELECTRICITY COMPANY ALDC - AREA LOAD DISPATCH CENTRE ANOVA - ANALYSIS OF VARIANCE. APM - ADVANCE POWER MANAGEMENT APPC - AVERAGE POWER PURCHASE COST APSEB - ANDHAR PRADESH STATE ELECTRICITY BOARD. APTEL - APPELLATE TRIBUNAL FOR ELECTRICITY ARR - AVERAGE REVENUE REALISED AT&C - AGGREGATE TECHNICAL & COMMERCIAL LOSSES AUX - AUXILIARY BECL - BHAVNAGAR ENERGY COMPANY LIMITED BEE - BUREAU OF ENERGY EFFICIENCY BFP - BOILER FEED PUMP BHEL - BHARAT HEAVY ELECTRICALS LIMITED BOP - BALANCE OF PLANTS. BRICS - BRAZIL RUSSIA INDIA CHINA & SOUTH AFRICA BTG - BOILER TURBINE GENERATOR CAGR - COMPOUND ANNUAL GROWTH RATE CAPEX - CAPITAL EXPENDITURE CBDT - CENTRAL BOARD OF DIRECT TAXES CDM - CLEAN DEVELOPMENT MECHANISM CEA - CENTRAL ELECTRICITY AUTHORITY. CEICED - CHIEF ELECTRICAL INSPECTOR. CENVAT - CENTRALIZED VALUE ADDED TAX CER - CERTIFIED EMMISSION REDUCTION CERC - CENTRAL ELECTRICITY REGULATORY COMMISSION. CMIE - CENTRAL FOR MONITORING INDIA ECONOMY. XI CNG - COMPRESSED NATURAL GAS COC - COST OF CAPITAL COD - COMMERCIAL OPERATION DATE COGS - COST OF GOODS SOLD COP - COST OF PRODUCTION CPCB - CENTRAL POLLUTION BOARD CPL - COASTAL POWER LIMITED CPP - CAPTIVE POWER PLANT CPPs - CAPTIVE POWER PLANTS CRISIL - CREDIT RATING INFORMATION SERVICES OF INDIA LIMITED CSS - CROSS SUBSIDY SURCHARGE CST - CENTRAL SALES TAX CTU - CENTRAL TRANSMISSION UTILITY. CVPF -

Proposal for a Gujarati Script Root Zone Label Generation Ruleset (LGR)

Proposal for a Gujarati Root Zone LGR Neo-Brahmi Generation Panel Proposal for a Gujarati Script Root Zone Label Generation Ruleset (LGR) LGR Version: 3.0 Date: 2019-03-06 Document version: 3.6 Authors: Neo-Brahmi Generation Panel [NBGP] 1 General Information/ Overview/ Abstract The purpose of this document is to give an overview of the proposed Gujarati LGR in the XML format and the rationale behind the design decisions taken. It includes a discussion of relevant features of the script, the communities or languages using it, the process and methodology used and information on the contributors. The formal specification of the LGR can be found in the accompanying XML document: proposal-gujarati-lgr-06mar19-en.xml Labels for testing can be found in the accompanying text document: gujarati-test-labels-06mar19-en.txt 2 Script for which the LGR is proposed ISO 15924 Code: Gujr ISO 15924 Key N°: 320 ISO 15924 English Name: Gujarati Latin transliteration of native script name: gujarâtî Native name of the script: ગજુ રાતી Maximal Starting Repertoire (MSR) version: MSR-4 1 Proposal for a Gujarati Root Zone LGR Neo-Brahmi Generation Panel 3 Background on the Script and the Principal Languages Using it1 Gujarati (ગજુ રાતી) [also sometimes written as Gujerati, Gujarathi, Guzratee, Guujaratee, Gujrathi, and Gujerathi2] is an Indo-Aryan language native to the Indian state of Gujarat. It is part of the greater Indo-European language family. It is so named because Gujarati is the language of the Gujjars. Gujarati's origins can be traced back to Old Gujarati (circa 1100– 1500 AD). -

District Fact Sheet Junagadh Gujarat

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare National Family Health Survey - 4 2015 -16 District Fact Sheet Junagadh Gujarat International Institute for Population Sciences (Deemed University) Mumbai 1 Introduction The National Family Health Survey 2015-16 (NFHS-4), the fourth in the NFHS series, provides information on population, health and nutrition for India and each State / Union territory. NFHS-4, for the first time, provides district-level estimates for many important indicators. The contents of previous rounds of NFHS are generally retained and additional components are added from one round to another. In this round, information on malaria prevention, migration in the context of HIV, abortion, violence during pregnancy etc. have been added. The scope of clinical, anthropometric, and biochemical testing (CAB) or Biomarker component has been expanded to include measurement of blood pressure and blood glucose levels. NFHS-4 sample has been designed to provide district and higher level estimates of various indicators covered in the survey. However, estimates of indicators of sexual behaviour, husband’s background and woman’s work, HIV/AIDS knowledge, attitudes and behaviour, and, domestic violence will be available at State and national level only. As in the earlier rounds, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India designated International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai as the nodal agency to conduct NFHS-4. The main objective of each successive round of the NFHS has been to provide essential data on health and family welfare and emerging issues in this area. NFHS-4 data will be useful in setting benchmarks and examining the progress in health sector the country has made over time. -

India's Fragmented Social Protection System

Working Paper 2014-18 India’s Fragmented Social Protection System Three Rights Are in Place; Two Are Still Missing Santosh Mehrotra, Neha Kumra and Ankita Gandhi prepared for the UNRISD project on Towards Universal Social Security in Emerging Economies: Process, Institutions and Actors December 2014 UNRISD Working Papers are posted online to stimulate discussion and critical comment. The United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD) is an autonomous research institute within the UN system that undertakes multidisciplinary research and policy analysis on the social dimensions of contemporary development issues. Through our work we aim to ensure that social equity, inclusion and justice are central to development thinking, policy and practice. UNRISD, Palais des Nations 1211 Geneva 10, Switzerland Tel: +41 (0)22 9173020 Fax: +41 (0)22 9170650 [email protected] www.unrisd.org Copyright © United Nations Research Institute for Social Development This is not a formal UNRISD publication. The responsibility for opinions expressed in signed studies rests solely with their author(s), and availability on the UNRISD Web site (www.unrisd.org) does not constitute an endorsement by UNRISD of the opinions expressed in them. No publication or distribution of these papers is permitted without the prior authorization of the author(s), except for personal use. Contents Acronyms ......................................................................................................................... ii Summary ......................................................................................................................... -

Studies on the Flora of Periyar Tiger Reserv

KFRI Research Report 150 STUDIES ON THE FLORA OF PERIYAR TIGER RESERV N. Sas idharan KERALA FOREST RESEARCH INSTITUTE PEECHI, THRISSUR July 1998 Pages: 558 CONTENTS Page File Index to Families r.150.2 Abstract r.150.3 1 Introduction i r.150.4 2 Study Area ii r.150.5 3 Method viii r.150.6 4 Results viii r.150.7 5 Discussion xix r.150.8 6 Families 1 r.150.9 7 References 555 r.150.10 Index to families ACANTHACEAE 290 COCHLOSPERMACEAE 16 AGAVACEAE 452 COMBRETACEAE 133 AIZOACEAE 160 COMMELINACEAE 459 ALANGIACEAE 166 CONNARACEAE 85 AMARANTHACEAE 327 CONVOLVULACEAE 262 AMARYLLIDACEAE 452 CORNACEAE 166 ANACARDIACEAE 81 CRASSULACEAE 130 ANCISTROCLADACEAE 28 CUCURBITACEAE 153 ANNONACEAE 3 CYPERACEAE 481 APIACEAE 161 DATISCACEAE 158 APOCYNACEAE 240 DICHAPETALACEAE 62 AQUIFOLIACEAE 65 DILLENIACEAE 2 ARACEAE 471 DIOSCOREACEAE 453 ARALIACEAE 164 DIPTEROCARPACEAE 27 ARECACEAE 466 DROSERACEAE 131 ARISTOLOCHIACEAE 335 EBENACEAE 229 ASCLEPIADACEAE 246 ELAEGNACEAE 354 ASTERACEAE 190 ELAEOCARPACEAE 41 BALANOPHORACEAE 361 ERICACEAE 219 BALSAMINACEAE 44 ERIOCAULACEAE 477 BEGONIACEAE 159 ERYTHROXYLACEAE 42 BIGNONIACEAE 289 EUPHORBIACEAE 361 BOMBACACEAE 34 FABACEAE (LEGUMINOSAE) 86 BORAGINACEAE 260 FLACOURTIACEAE 17 BRASSICACEAE 13 GENTIANACEAE 256 BUDDLEJACEAE 256 GESNERIACEAE 287 BURMANNIACEAE 396 HAEMODORACEAE 451 BURSERACEAE 56 HALORAGACEAE 132 BUXACEAE 361 HIPPOCRATEACEAE 69 CAMPANULACEAE 215 HYDROCHARITACEAE 396 CANNABACEAE 389 HYPERICACEAE 23 CAPPARIDACEAE 14 HYPOXIDACEAE 453 CAPRIFOLIACEAE 166 ICACINACEAE 63 CARYOPHYLLACEAE 22 JUNCACEAE 466 CELASTRACEAE