Opinnäytteen Nimi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chen Man Fearless & Fabulous 9 December–4 March 2018

Press release 1/2 Chen Man Fearless & Fabulous 9 December–4 March 2018 The title says it all: Fearless & Fabulous. It takes both courage and magnetic For images, please contact attraction to achieve the position held by Chinese photographer Chen Man. And Fotografiska’s Head of Communications Margita Ingwall +46 (0)70 456 14 61 her success is a significant (Chinese) sign of the time. Chen Man is undoubtedly [email protected] the pioneer of China’s fashion photographer. Throughout the years, Chen Man has firmly established herself as the most sought-after and certainly the highest paid fashion and portrait photographer in China. Her works have featured across a range of leading publications, including Vogue, Elle, Harper’s Bazaar, Cosmopolitan and i.D. Her vigorously retouched images comprise several layers of narrative and in her pictorial world the current image of China is interpreted and reinterpreted. In a country in convulsions between the old and the new, Chen Man may be regarded as a representative of her generation – the Generation Y, as in »why«. In her photographs, Chen Man stages fusions between the past and the present, east and west, tradition and renewal, questioning and reformulating norms and beauty ideals. Film stars and captains of industry all want to be photographed by her. Her megastar status defies description, as she moves in the most varied of social circles of the Chinese elite. China’s No.1 leading actress Fan Bingbing will only be photographed by Chen Man, international superstars such as Rihanna, Keanu Reeves and Nicole Kidman come to China to be portrayed by Chen Man. -

UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Beyond New Waves: Gender and Sexuality in Sinophone Women's Cinema from the 1980s to the 2000s Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4h13x81f Author Kang, Kai Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Beyond New Waves: Gender and Sexuality in Sinophone Women‘s Cinema from the 1980s to the 2000s A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature by Kai Kang March 2015 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Marguerite Waller, Chairperson Dr. Lan Duong Dr. Tamara Ho Copyright by Kai Kang 2015 The Dissertation of Kai Kang is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements My deepest gratitude is to my chair, Dr. Marguerite Waller who gave me freedom to explore my interested areas. Her advice and feedback helped me overcome many difficulties during the writing process. I am grateful to Dr. Lan Duong, who not only offered me much valuable feedback to my dissertation but also shared her job hunting experience with me. I would like to thank Dr Tamara Ho for her useful comments on my work. Finally, I would like to thank Dr. Mustafa Bal, the editor-in-chief of The Human, for having permitted me to use certain passages of my previously published article ―Inside/Outside the Nation-State: Screening Women and History in Song of the Exile and Woman, Demon, Human,‖ in my dissertation. iv ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Beyond New Waves: Gender and Sexuality in Sinophone Women‘s Cinema from the 1980s to the 2000s by Kai Kang Doctor of Philosophy, Graduate Program in Comparative Literature University of California, Riverside, March 2015 Dr. -

Art, Politics, and Commerce in Chinese Cinema

Art, Politics, and Commerce in Chinese Cinema edited by Ying Zhu and Stanley Rosen Hong Kong University Press 14/F Hing Wai Centre, 7 Tin Wan Praya Road, Aberdeen, Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © Hong Kong University Press 2010 Hardcover ISBN 978-962-209-175-7 Paperback ISBN 978-962-209-176-4 All rights reserved. Copyright of extracts and photographs belongs to the original sources. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the copyright owners. Printed and bound by XXXXX, Hong Kong, China Contents List of Tables vii Acknowledgements ix List of Contributors xiii Introduction 1 Ying Zhu and Stanley Rosen Part 1 Film Industry: Local and Global Markets 15 1. The Evolution of Chinese Film as an Industry 17 Ying Zhu and Seio Nakajima 2. Chinese Cinema’s International Market 35 Stanley Rosen 3. American Films in China Prior to 1950 55 Zhiwei Xiao 4. Piracy and the DVD/VCD Market: Contradictions and Paradoxes 71 Shujen Wang Part 2 Film Politics: Genre and Reception 85 5. The Triumph of Cinema: Chinese Film Culture 87 from the 1960s to the 1980s Paul Clark vi Contents 6. The Martial Arts Film in Chinese Cinema: Historicism and the National 99 Stephen Teo 7. Chinese Animation Film: From Experimentation to Digitalization 111 John A. Lent and Ying Xu 8. Of Institutional Supervision and Individual Subjectivity: 127 The History and Current State of Chinese Documentary Yingjin Zhang Part 3 Film Art: Style and Authorship 143 9. -

1St China Onscreen Biennial

2012 1st China Onscreen Biennial LOS ANGELES 10.13 ~ 10.31 WASHINGTON, DC 10.26 ~ 11.11 Presented by CONTENTS Welcome 2 UCLA Confucius Institute in partnership with Features 4 Los Angeles 1st China Onscreen UCLA Film & Television Archive All Apologies Biennial Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Are We Really So Far from the Madhouse? Film at REDCAT Pomona College 2012 Beijing Flickers — Pop-Up Photography Exhibition and Film Seeding cross-cultural The Cremator dialogue through the The Ditch art of film Double Xposure Washington, DC Feng Shui Freer and Sackler Galleries of the Smithsonian Institution Confucius Institute at George Mason University Lacuna — Opening Night Confucius Institute at the University of Maryland The Monkey King: Uproar in Heaven 3D Confucius Institute Painted Skin: The Resurrection at Mason 乔治梅森大学 孔子学院 Sauna on Moon Three Sisters The 2012 inaugural COB has been made possible with Shorts 17 generous support from the following Program Sponsors Stephen Lesser The People’s Secretary UCLA Center for Chinese Studies Shanghai Strangers — Opening Night UCLA Center for Global Management (CGM) UCLA Center for Management of Enterprise in Media, Entertainment and Sports (MEMES) Some Actions Which Haven’t Been Defined Yet in the Revolution Shanghai Jiao Tong University Chinatown Business Improvement District Mandarin Plaza Panel Discussion 18 Lois Lambert of the Lois Lambert Gallery Film As Culture | Culture in Film Queer China Onscreen 19 Our Story: 10 Years of Guerrilla Warfare of the Beijing Queer Film Festival and -

Laurel Films, Dream Factory, Rosem Films and Fantasy Pictures Present

Laurel Films, Dream Factory, Rosem Films and Fantasy Pictures present A Chinese – French coproduction SUMMER PALACE a film by Lou Ye with Hao Lei Guo Xiaodong Hu Ling Zhang Xianmin 2h20 / 35mm / 1.66 / Dolby SRD / Original language: Chinese, German INTERNATIONAL SALES Wild Bunch 99 RUE DE LA VERRERIE 75004 PARIS - France tel.: +33 1 53 01 50 30 fax: +33 1 53 01 50 49 email [email protected] www.wildbunch.biz Wild Bunch CANNES OFFICE 23 rue Macé , 4th floor Phone: +33 4 93 99 31 68 Fax: +33 4 93 99 64 77 VINCENT MARAVAL cell: +33 6 11 91 23 93 [email protected] GAEL NOUAILLE cell: +33 6 21 23 04 72 [email protected] CAROLE BARATON cell: +33 6 20 36 77 72 [email protected] SILVIA SIMONUTTI cell: +33 6 20 74 95 08 [email protected] INTERNATIONAL PRESS: PR contact All Suites Garden Studio, All Suites Residence, 12 rue Latour Maubourg 06400 Cannes Phil SYMES tel.: + 33 6 09 23 86 37 Ronaldo MOURAO tel.: + 33 6 09 28 89 55 Virginia GARCIA tel.: +33 6 18 55 93 62 Cristina SIBALDI tel.: + 33 6 23 25 78 31 Email: [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Stills and press kit downloadable on www.ocean-films.com/presse Synopsis China, 1989 Two young lovers play out their complex, erotic, love/hate relationship against a volatile backdrop of political unrest. Beautiful Yu Hong leaves her village, her family and her boyfriend to study in Beijing, where she discovers a world of intense sexual and emotional experimentation, and falls madly in love with fellow student Zhou Wei. -

Industry Guide Focus Asia & Ttb / April 29Th - May 3Rd Ideazione E Realizzazione Organization

INDUSTRY GUIDE FOCUS ASIA & TTB / APRIL 29TH - MAY 3RD IDEAZIONE E REALIZZAZIONE ORGANIZATION CON / WITH CON IL CONTRIBUTO DI / WITH THE SUPPORT OF IN COLLABORAZIONE CON / IN COLLABORATION WITH CON LA PARTECIPAZIONE DI / WITH THE PARTICIPATION OF CON IL PATROCINIO DI / UNDER THE PATRONAGE OF FOCUS ASIA CON IL SUPPORTO DI/WITH THE SUPPORT OF IN COLLABORAZIONE CON/WITH COLLABORATION WITH INTERNATIONAL PARTNERS PROJECT MARKET PARTNERS TIES THAT BIND CON IL SUPPORTO DI/WITH THE SUPPORT OF CAMPUS CON LA PARTECIPAZIONE DI/WITH THE PARTICIPATION OF MAIN SPONSORS OFFICIAL SPONSORS FESTIVAL PARTNERS TECHNICAL PARTNERS ® MAIN MEDIA PARTNERS MEDIA PARTNERS CON / WITH FOCUS ASIA April 30/May 2, 2019 – Udine After the big success of the last edition, the Far East Film Festival is thrilled to welcome to Udine more than 200 international industry professionals taking part in FOCUS ASIA 2019! This year again, the programme will include a large number of events meant to foster professional and artistic exchanges between Asia and Europe. The All Genres Project Market will present 15 exciting projects in development coming from 10 different countries. The final line up will feature a large variety of genres and a great diversity of profiles of directors and producers, proving one of the main goals of the platform: to explore both the present and future generation of filmmakers from both continents. For the first time the market will include a Chinese focus, exposing 6 titles coming from China, Hong Kong and Taiwan. Thanks to the partnership with Trieste Science+Fiction Festival and European Film Promotion, Focus Asia 2019 will host the section Get Ready for Cannes offering to 12 international sales agents the chance to introduce their most recent line up to more than 40 buyers from Asia, Europe and North America. -

The Changing Face of Korean Cinema, 1960 to 2015 / Brian Yecies and Ae-Gyung Shim

The Changing Face of Korean Cinema The rapid development of Korean cinema during the decades of the 1960s and 2000s reveals a dynamic cinematic history that runs parallel to the nation’s politi- cal, social, economic, and cultural transformation during these formative periods. This book examines the ways in which South Korean cinema has undergone a transformation from an antiquated local industry in the 1960s into a thriving international cinema in the twenty-first century. It investigates the circumstances that allowed these two eras to emerge as creative watersheds and demonstrates the forces behind Korea’s positioning of itself as an important contributor to regional and global culture, especially its interplay with Japan, Greater China, and the United States. Beginning with an explanation of the understudied operations of the film industry during its 1960s take-off, it then offers insight into the challenges that producers, directors, and policy makers faced in the 1970s and 1980s during the most volatile part of Park Chung Hee’s authoritarian rule and the subsequent Chun Doo-hwan military government. It moves on to explore the film industry’s profes- sionalization in the 1990s and subsequent international expansion in the 2000s. In doing so, it explores the nexus and tensions of film policy, producing, directing, genres, and the internationalization of Korean cinema over half a century. By highlighting the recent transnational turn in national cinemas, this book underscores the impact of developments pioneered by Korean cinema on the transformation of “Planet Hallyuwood”. It will be of particular interest to students and scholars of Korean Studies and Film Studies. -

Yang Obeys, but the Yin Ignores: Copyright Law and Speech Suppression in the People's Republic of China

UCLA UCLA Pacific Basin Law Journal Title The Yang Obeys, but the Yin Ignores: Copyright Law and Speech Suppression in the People's Republic of China Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4j750316 Journal UCLA Pacific Basin Law Journal, 29(1) Author McIntyre, Stephen Publication Date 2011 DOI 10.5070/P8291022233 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California THE YANG OBEYS, BUT THE YIN IGNORES: COPYRIGHT LAW AND SPEECH SUPPRESSION IN THE PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF CHINA Stephen McIntyret ABSTRACT Copyright law can either promote or restrict free speech: while copyright preserves economic incentives to create and pub- lish new expression, it also fences off expression from public use. For this reason, the effect of copyright law on speech in a given country depends on the particular manner in which it is under- stood, legislated, and enforced. This Article argues that copyright law in the People's Repub- lic of China (PRC) serves as a tool for speech suppression and censorship. Whereas China has engaged in official censorship for thousands of years, there has historically been little appreciation for proprietary rights in art and literature. Just as China's early twentieth century attempts to recognize copyright overlapped with strict publication controls, the PRC's modern copyright regime embodies the view that copyright is a mechanism for policing speech and media. The decade-long debate that preceded the PRC's first copy- right statute was shaped by misunderstanding,politics, ideology, and historicalforces. Scholars and lawmakers widely advocated that Chinese copyright law discriminate based on media content and carefully circumscribe authors' rights. -

1/14 Lost in Beijing: Ruthless Profiteer and Decadence of Family Values

2012 American Comparative Literature Association Annual Meeting Ho Lost in Beijing: Ruthless Profiteer and Decadence of Family Values as Social Commentary and Its Limits Lost in Beijing: Ruthless Profiteer and Decadence of Family Values as Social Commentary and Its Limits ©Wing Shan Ho Speedy economic development in neo-liberal China has generated significant anxiety about the impact of the prevalent money-oriented economic order on subjectivity and the private sphere. As Chinese citizens from all walks of life become more conscious of profits/benefits (li), the urge to acquire money and the pressure to strive for a viable livelihood might be felt more keenly by the social underclass. How do members of the underclass respond to the changing economic order? What are they willing to sacrifice for economic survival and in the pursuit of affluence? How have the concepts of self, family, and community changed accordingly? These questions lead me to examine the state-criticized film Lost in Beijing (Pingguo) (Li Yu, 2007), which portrays a ruthless economic subjects who destroys family bonds and affection. This article offers a contextualized, close reading of Lost in Beijing and explores how filmic representation offers social commentary through dramatized conflicts between money and family values. I argue that Lost in Beijing, which portrays the selling of a son, critiques the logic of capitalism and monetary profit for the way in which it reduces human beings and affective bonding to mere commodities. Such a critical attitude results in not only portrayals of a ruthless economic subject but also sympathy of female victims of China’s economic growth whose depictions elicit the state’s censure. -

Sexualities in Underground Films in the Contemporary PR China

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Communication Theses Department of Communication Spring 5-2011 Imagining Queerness: Sexualities in Underground Films in the Contemporary P. R. China Jin Zhao Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_theses Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Zhao, Jin, "Imagining Queerness: Sexualities in Underground Films in the Contemporary P. R. China." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2011. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_theses/73 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Communication at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IMAGINING QUEERNESS: SEXUALITIES IN UNDERGROUND FILMS IN THE CONTEMPORARY P. R. CHINA By JIN ZHAO Under the Direction of Leonard R. Teel ABSTRACT In response to the globalizing queerness argument and the cultural specificity argument in queer cultural studies, this thesis examines the emerging modern queer identity and culture in the contemporary People’s Republic of China (PRC) in an intercultural context. Recognizing Chinese queer culture as an unstable, transforming and complex collection of congruent and/or contesting meanings, not only originated in China but also traveling across cultures, this thesis aims to exorcise the reified images of Chinese queers, or tongzhi, to contribute to the understanding of a dynamic construction of Chinese queerness at the turn of a new century, and to lend insight on the complicity of the elements at play in this construction by analyzing the underground films with queer content made in the PRC. -

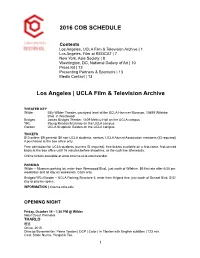

2016 COB Release Genb8.Pages

2016 COB SCHEDULE Contents Los Angeles, UCLA Film & Television Archive | 1 Los Angeles, Film at REDCAT | 7 New York, Asia Society | 8 Washington, DC, National Gallery of Art | 10 Press Kit | 12 Presenting Partners & Sponsors | 13 Media Contact | 13 Los Angeles | UCLA Film & Television Archive THEATER KEY Wilder Billy Wilder Theater, courtyard level of the UCLA Hammer Museum, 10899 Wilshire Blvd. in Westwood Bridges James Bridges Theater, 1409 Melnitz Hall on the UCLA campus YRL Young Research Library on the UCLA campus Garden UCLA Sculpture Garden on the UCLA campus TICKETS $10 online; $9 general; $8 non-UCLA students, seniors, UCLA Alumni Association members (ID required) if purchased at the box office only. Free admission for UCLA students (current ID required); free tickets available on a first-come, first-served basis at the box office until 15 minutes before showtime, or the rush line afterwards. Online tickets available at www.cinema.ucla.edu/calendar. PARKING Wilder – Museum parking lot; enter from Westwood Blvd., just north of Wilshire. $6 flat rate after 6:00 pm weekdays and all day on weekends. Cash only. Bridges/YRL/Garden – UCLA Parking Structure 3; enter from Hilgard Ave. just south of Sunset Blvd. $12/ day or pay-by-space. INFORMATION | cinema.ucla.edu OPENING NIGHT Friday, October 14 • 7:30 PM @ Wilder West Coast Premiere THARLO र၎ China, 2015 Director/Screenwriter: Pema Tseden | DCP | Color | In Tibetan with English subtitles | 123 min. Cast: Shide Nyima, Yangshik Tso. !1 Tibetan sheep-herder Tharlo journeys from his remote village to get a photo ID in the nearest town of Qinghai province where he meets a city woman whose romantic intentions may not be what they first seem. -

Yimeng Jin, Writer/Director One Night Surprise and Sophie's Revenge

Yimeng Jin, Writer/Director One Night Surprise and Sophie’s Revenge Yimeng Jin (aka Eva Jin), born in China, is writer/director of several feature films. Her most recent feature film One Night Surprise (2013), a romantic comedy starring Fan Bingbing, Aarif Rahman, Daniel Henney, and Jiang Jinfu, grossed over 170M RMB ($28M USD) and was the leading film on Chinese Valentine’s Day (Aug 13) in 2013. Her previous feature film Sophie's Revenge (2009), a romantic comedy starring Zhang Ziyi, Peter Ho, So Ji-seob, and Fan Bingbing, earned 100M RMB ($15M USD) in China, making her the first female director to break the symbolic 100M RMB box office barrier and the first filmmaker to prove a romantic comedy could be a large scale commercial success in China. Previously, she wrote and directed Sailfish (2008), a sports drama set during the Cultural Revolution that was made for release during the Beijing Olympic Games. Her short film, The 17th Man (2004), won third place at the 2004 Student Emmy Awards, Best Director, Best Script and Best Art Direction at the 2004 Fearless Tale Film Festival, Best Lounge Short at Sonoma film festival, and was an Official Selection in Cannes Film Festival (2004). She was also a pop music singer and cartoonist who published three cartoon books in 2001 and 2009 with the Beijing Publishing House. She graduated with a bachelor's degree in Italian Opera at the China Conservancy of Music, and a Master's in Filmmaking from Florida State University's Film School. .