Download File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catalogo-Festivaldorio-2015.Pdf

Sumário TABLE OF CONTENTS 012 APRESENTAÇÃO PRESENTATION 023 GALA DE ABERTURA OPENNING NIGHT GALA 025 GALA DE ENCERRAMENTO CLOSING NIGHT GALA 033 PREMIERE BRASIL PREMIERE BRASIL 079 PANORAMA GRANDES MESTRES PANORAMA: MASTERS 099 PANORAMA DO CINEMA MUNDIAL WORLD PANORAMA 2015 141 EXPECTATIVA 2015 EXPECTATIONS 2015 193 PREMIERE LATINA LATIN PREMIERE 213 MIDNIGHT MOVIES MIDNIGHT MOVIES 229 MIDNIGHT DOCS MIDNIGHT DOCS 245 FILME DOC FILM DOC 251 ITINERÁRIOS ÚNICOS UNIQUE ITINERARIES 267 FRONTEIRAS FRONTIERS 283 MEIO AMBIENTE THREATENED ENVIRONMENT 293 MOSTRA GERAÇÃO GENERATION 303 ORSON WELLS IN RIO ORSON WELLS IN RIO 317 STUDIO GHIBLI - A LOUCURA E OS SONHOS STUDIO GHIBLI - THE MADNESS AND THE DREAMS 329 LIÇÃO DE CINEMA COM HAL HARTLEY CINEMA LESSON WITH HAL HARTLEY 333 NOIR MEXICANO MEXICAN FILM NOIR 343 PERSONALIDADE FIPRESCI LATINO-AMERICANA DO ANO FIPRESCI’S LATIN AMERICAN PERSONALITY OF THE YEAR 349 PRÊMIO FELIX FELIX AWARD 357 HOMENAGEM A JYTTE JENSEN A TRIBUTE TO JYTTE JENSEN 361 FOX SEARCHLIGHT 20 ANOS FOX SEARCHLIGHT 20 YEARS 365 JÚRIS JURIES 369 CINE ENCONTRO CINE CHAT 373 RIOMARKET RIOMARKET 377 A ETERNA MAGIA DO CINEMA THE ETERNAL MAGIC OF CINEMA 383 PARCEIROS PARTNERS AND SUPPLIES 399 CRÉDITOS E AGRADECIMENTOS CREDITS AND AKNOWLEDGEMENTS 415 ÍNDICES INDEX CARIOCA DE CORPO E ALMA CARIOCA BODY AND SOUL Cidade que provoca encantamento ao olhar, o Rio Enchanting to look at, Rio de Janeiro will once de Janeiro estará mais uma vez no primeiro plano again take centre stage in world cinema do cinema mundial entre os dias 1º e 14 de ou- between the 1st and 14th of October. -

L'amant D'un Jour

L’AMANT D'UN JOUR DIRECTED BY PHILIPPE GARREL // 2017 // FRANCE // 76 MIN Contact Information — U.S. Contact Information — U.K. Media: Julia Pacetti, JMP Verdant Publicity: Chris Boyd, Organic [email protected] / 718 399 0400 [email protected] / 020 3372 0970 Booking: Ian Stimler and Mika Kimoto, KimStim Booking: Martin Myers [email protected] / [email protected] [email protected] For all other questions, contact Lilly Riber, MUBI For all other questions, contact Sanam Gharagozlou, MUBI [email protected] / 803 479 3737 [email protected] / 07407 713406 Synopsis After a devastating breakup, the only place twenty-three-year old Lover for a Day premiered in the Directors’ Fortnight at Cannes, where Jeanne has to stay in Paris is the small flat of her father, Giles. But it was awarded the SACD prize from the French Writers and Directors when Jeanne arrives, she finds that her father’s new girlfriend has Guild, and is an Official Selection of the 2017 New York Film Festival. moved in too: Arianne, a young woman her own age. Each is looking for their own kind of love in a city filled with possibilities. Reviews “Alluring and very elegantly crafted” Variety “A bittersweet, and intoxicating study of relationships in flux” The Film Stage “The images—exquisitely shadowed black-and-white 35mm— give the narrative a timelessness that is precisely the point of Garrel’s enterprise” Film Comment “Delectable” ScreenDaily “The film benefits from the collective contributions of four screenwriters… whose collective insights result in a beautiful -

Festival Catalogue 2015

Jio MAMI 17th MUMBAI FILM FESTIVAL with 29 OCTOBER–5 NOVEMBER 2015 1 2 3 4 5 12 October 2015 MESSAGE I am pleased to know that the 17th Jio MAMI Mumbai Film Festival is being organised by the Mumbai Academy of Moving Image (MAMI) in Mumbai from 29th October to 5th November 2015. Mumbai is the undisputed capital of Indian cinema. This festival celebrates Mumbai’s long and fruitful relationship with cinema. For the past sixteen years, the festival has continued promoting cultural and MRXIPPIGXYEP I\GLERKI FIX[IIR ½PQ MRHYWXV]QIHME TVSJIWWMSREPW ERH GMRIQE IRXLYWMEWXW%W E QYGL awaited annual culktural event, this festival directs international focus to Mumbai and its continued success highlights the prominence of the city as a global cultural capital. I am also happy to note that the 5th Mumbai Film Mart will also be held as part of the 17th Mumbai Film Festival, ensuring wider distribution for our cinema. I congratulate the Mumbai Academy of Moving Image for its continued good work and renewed vision and wish the 17th Jio MAMI Mumbai Film Festival and Mumbai Film Mart grand success. (CH Vidyasagar Rao) 6 MESSAGE Mumbai, with its legacy, vibrancy and cultural milieu, is globally recognised as a Financial, Commercial and Cultural hub. Driven by spirited Mumbaikars with an indomitable spirit and great affection for the city, it has always promoted inclusion and progress whilst maintaining its social fabric. ,SQIXSXLI,MRHMERH1EVEXLM½PQMRHYWXV]1YQFEMMWXLIYRHMWTYXIH*MPQ'ETMXEPSJXLIGSYRXV] +MZIRXLEX&SPP][SSHMWXLIQSWXTVSPM½GMRHYWXV]MRXLI[SVPHMXMWSRP]FI½XXMRKXLEXE*MPQ*IWXMZEP that celebrates world cinema in its various genres is hosted in Mumbai. -

Es Un Proyecto De

Es un proyecto de Una publicación del ICAS – Instituto de la Cultura y las Artes de Sevilla ISBN: 978-84-9102-020-2 DEPÓSITO LEGAL: SE 1454-2015 2 PRESENTACIÓN JUAN ESPADAS ALCALDE DE SEVILLA Pensar en cine europeo es pensar en Sevilla. Son ya doce los años que lleva celebrándose nuestro Festival de Cine Europeo, y cada edición confirma y amplía To think of European cinema is to think of Seville. We las expectativas y el éxito del anterior, consolidando have been celebrating our European Film Festival una oferta cultural que cada año reúne a decenas de for twelve years now, and each edition confirms miles de espectadores en las salas de cine de nuestra and increases the expectations and the success of ciudad. the previous one, consolidating a cultural offer that La cultura es la mejor forma de la que disponemos each year draws thousands of spectators to our city’s para proyectarnos al mundo y para reflexionar cinemas. sobre nosotros mismos, es eje y motor de nuestro Culture is the best way we have to show ourselves crecimiento. Gracias a ella nos observamos en los to the world and to think about ourselves, it is the demás. Nuestra ciudad debe ser una ciudad abierta a axes and the engine of our growth. Thanks to it we nuevas gentes y nuevas tendencias, una ciudad que can observe ourselves in others. Our city must be aproveche todo el dinamismo y la vida de una cultura a city that is open to new people and new trends, a activa y siempre cambiante. -

Eric Caravaca Esther Garrel Louise Chevillotte a Film By

SAÏD BEN SAÏD & MICHEL MERKT PRESENT ERIC CARAVACA ESTHER GARREL LOUISE CHEVILLOTTE CRÉDITS NON CONTRACTUELS CRÉDITS (L’AMANT D’UN JOUR) A FILM BY PHILIPPE GARREL PHOTOS : © 2016 GUY FERRANDIS / SBS FILMS PHOTOS : © 2016 GUY FERRANDIS / SBS FILMS FILMOGRAPHY PHILIPPE GARREL 2017 LOVER FOR A DAY 2014 IN THE SHADOW OF WOMEN 2013 JEALOUSY In Competition, Venice 2013 2011 THAT SUMMER In Competition, Venice 2011 2005 FRONTIER OF DAWN Official Selection, Cannes 2008 2004 REGULAR LOVERS Silver Lion, Venice 2005 Louis Delluc award 2005 FRIPESCI Prize European Discovery, 2006 2001 WILD INNOCENCE International Critics’ Award, Venice 2001 1998 NIGHT WIND 1995 LE CŒUR FANTÔME films together without the lights being brought up 1993 LA NAISSANCE DE L’AMOUR between them. Before that, Athanor had been SYNOPSIS 1990 J’ENTENDS PLUS LA GUITARE attacked by a critic, who said I was banging my This is the story of a father, his 23-year-old Silver Lion, Venice 1991 head against a wall, against the obvious fact that daughter, who goes back home one day because 1988 LES BAISERS DE SECOURS she has just been dumped, and his new girlfriend, cinema was movement. La Cicatrice was tracking who is also 23 and lives with him. shots and music. Athanor was silence and still 1984 ELLE A PASSÉ TANT D’HEURES shots. Then it was back to Le Berceau with Ash SOUS LES SUNLIGHTS Ra Tempel’s music. So Athanor worked fine as an 1984 RUE FONTAINE (short) interlude between two parts of a concert. This 1983 LIBERTÉ, LA NUIT DIRECTOR’S NOTE time, it is a trilogy; the films are not made to be Perspective Award, Cannes 1984 screened together. -

Sight & Sound Annual Index 2017

THE INTERNATIONAL FILM MAGAZINE Index to Volume 27 January to December 2017 Compiled by Patricia Coward How to use this Index The first number after a title refers to the issue month, and the second and subsequent numbers are the page references. Eg: 8:9, 32 (August, page 9 and page 32). THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT TO SIGHT & SOUND SUBJECT INDEX SUBJECT INDEX After the Storm (2016) 6:52(r) Amour (2012) 5:17; 6:17 Armano Iannucci Shows, The 11:42 Ask the Dust 2:5 Bakewell, Sarah 9:32 Film review titles are also interview with Koreeda Amours de minuit, Les 9:14 Armisen, Fred 8:38 Asmara, Abigail 11:22 Balaban, Bob 5:54 included and are indicated by Hirokazu 7:8-9 Ampolsk, Alan G. 6:40 Armstrong, Jesse 11:41 Asquith, Anthony 2:9; 5:41, Balasz, Béla 8:40 (r) after the reference; age and cinema Amy 11:38 Army 2:24 46; 10:10, 18, 44 Balch, Antony 2:10 (b) after reference indicates Hotel Salvation 9:8-9, 66(r) An Seohyun 7:32 Army of Shadows, The Assange, Julian Balcon, Michael 2:10; 5:42 a book review Age of Innocence, The (1993) 2:18 Anchors Aweigh 1:25 key sequence showing Risk 8:50-1, 56(r) Balfour, Betty use of abstraction 2:34 Anderson, Adisa 6:42 Melville’s iconicism 9:32, 38 Assassin, The (1961) 3:58 survey of her career A Age of Shadows, The 4:72(r) Anderson, Gillian 3:15 Arnold, Andrea 1:42; 6:8; Assassin, The (2015) 1:44 and films 11:21 Abacus Small Enough to Jail 8:60(r) Agony of Love (1966) 11:19 Anderson, Joseph 11:46 7:51; 9:9; 11:11 Assassination (1964) 2:18 Balin, Mireille 4:52 Abandon Normal Devices Agosto (2014) 5:59 Anderson, Judith 3:35 Arnold, David 1:8 Assassination of the Duke Ball, Wes 3:19 Festival 2017, Castleton 9:7 Ahlberg, Marc 11:19 Anderson, Paul Thomas Aronofsky, Darren 4:57 of Guise, The 7:95 Ballad of Narayama, The Abdi, Barkhad 12:24 Ahmed, Riz 1:53 1:11; 2:30; 4:15 mother! 11:5, 14, 76(r) Assassination of Trotsky, The 1:39 (1958) 11:47 Abel, Tom 12:9 Ahwesh, Peggy 12:19 Anderson, Paul W.S. -

FRENCH DISTRIBUTION AD VITAM Advitamdistribution.Com

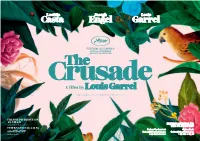

WHY NOT PRODUCTIONS PRESENTS FRANCE – 2021 – 1.66 – 5.1 / COLOR RUNNING TIME: 1H06 FRENCH DISTRIBUTION AD VITAM INTERNATIONAL PR advitamdistribution.com THE PR FACTORY INTERNATIONAL SALES Barbara Von Lombeek Gudrun Burie [email protected] [email protected] wildbunch.biz + 32 486 54 64 80 + 32 498 10 10 01 The Crusade The Crusade Synopsis Abel and Marianne discover that their 13-year-old son Joseph has secretly sold their most precious possessions. They soon find out that Joseph is not the only one – all over the world, hundreds of children have joined forces to finance a mysterious project. Their mission is to save the planet. 3 4 The Crusade The Crusade Interview with Louis Garrel Did the idea for The Crusade come from discussions make this film or else it would look like I was chasing you may have had with the younger generation? after the event. And this is indeed what is happening Not at all! It’s much crazier. Jean-Claude – the proof lies in your first question. I like that The (Carrière) and I were on a plane coming back from Crusade has a “live coverage” side to it, but had New York, he told me he had a very good idea for I listened to Jean-Claude, I would have been ahead! a scene. He got lots of ideas above the clouds. In I was cowardly, or not visionary enough. But at the Paris he read me the scene, which later become time, this quasi-anthropological collective surge of the first scene of The Crusade. -

Philippe Garrel

RECTANGLE PRODUCTIONS PRESENTS THE SALT OF TEARS A FILM BY PHILIPPE GARREL ORIGINAL MUSIc JEAN-LOUIS AUBERT BENJAMIN BALTIMORE • © Photos GUY FRERRANDIS RECTANGLE PRODUCTIONS PRESENTS ‘ THE SALT OF TEARS A FILM BY PHILIPPE GARREL WITH Logann Oulaya André ANTUOFERMO AMAMRA WILMS Louise Souheila CHEVILLOTTE YACOUB 2019 / FRANCE / BLACK AND WHITE / 1H40 INTERNATIONAL SALES INTERNATIONAL PR WILD BUNCH INTERNATIONAL MAGALI MONTET +33 6 71 63 36 16 EVA DIEDERIX [email protected] [email protected] SILVIA SIMONUTTI [email protected] FRANCESCA DOLZANI + 33 6 50 08 09 18 FANNY OSTOJIC [email protected] [email protected] PHOTOS AND PRESS KIT cAN BE DOWNLOADED FROM https://www.wildbunch.biz/movie/the-salt-of-tears/ SYNOPSIS A young man’s first female conquests and the deep love he feels for his father. The story of Luc, a young man from the provinces, who visits Paris to sit his arts and craft college entry exam. In the street he meets Djemila, with whom he enjoys a brief romance. Returning to his father’s house, he begins a relationship with his childhood friend Geneviève, while Djemila longs to see him again. When Luc is accepted by the college he leaves once more for Paris, leaving Geneviève and the baby she is carrying behind him… INTERVIEW WITH PHILIPPE GARREL It seems that since Jealousy your cinema has entered a new cycle: an intimate focus on the couple and the family, black and white photography, a stripped back style, regular collaborations with writers Jean-Claude Carrière and Arlette Langmann, cinematographer Renato Berta, composer Jean-Louis Aubert… Do you conscientiously operate in cycles, or is it more intuitive? This idea of the cycle is a fair point. -

Jean-Claude Carrière

SAÏD BEN SAÏD und MICHEL MERKT zeigen CLOTILDE COURAU STANISLAS MERHAR LENA PAUGAM in einem Film von PHILIPPE GARREL IM SCHATTEN DER FRAUEN L’Ombre des femmes Ab 28. Januar 2016 im Kino im Verleih von SCHWARZWEISS FILMVERLEIH Pressematerial: www.schwarzweiss-filmverleih.de Technische Daten Frankreich / Schweiz 2015 Länge: 73 Minuten Bildformat: CinemaScope 1: 2,35 Tonformat: 5.1 VERLEIH PRESSE Schwarz-Weiss Filmverleih OHG Filmpresse Meuser Goebenstr. 30 Ederstr. 10 53113 Bonn 60486 Frankfurt am Main Tel.: 0228 –22 91 79 Tel.: 069 – 40 58 04 17 Fax: 0228 – 22 15 22 Fax: 069 – 40 58 04 13 [email protected] [email protected] www.schwarzweiss-filmverleih.de www.filmpresse-meuser.de Presse-Material: www.schwarzweiss-filmverleih.de 2 Kurzinhalt: Ein Liebesdrama über das Verhältnis der Geschlechter. Manon und Pierre sind seit langem ein Paar. Während Manon mit ihrem Leben zufrieden ist, verzweifelt Pierre an den gesellschaftlichen Konventionen Erfolg und Treue, die er beide nicht erfüllen kann. IM SCHATTEN DER FRAUEN war der Eröffnungsfilm der Quinzaine des Réalisateurs in Cannes 2015 Langinhalt: Manon und Pierre sind seit langem ein Paar. Ihr Alltag hat ihre Gefühle für einander fest im Griff. Sie sind eigentlich gleich stark, sie bewerten sich nur ganz unterschiedlich. Manon glaubt fest an Pierre und den Sinn seiner Arbeit als Filmemacher. Sie ist damit zufrieden, dass sie die aktivere von beiden ist und Pierre mit allen Kräften bei seiner Arbeit unterstützen kann. Manon hat eine Affäre mit einem anderen Mann, von der Pierre nichts ahnt, weil das für Manon ganz selbstverständlich ist. Pierre dagegen ist deprimiert, die Jahre lange Erfolglosigkeit zehrt an seinem Selbstbewusstsein. -

Palestine Festival

APRIL 018 GAZETTE 2 ■ Vol. 46, No. 4 17TH ANNUAL CHICAGO PALESTINE FESTIVAL MORE FRIDAY MATINEES! THE JUDGE, May 3 OPEN-CAPTIONED SCREENINGS! ALSO: Asian American Showcase, 164 N. State Street Lucrecia Martel www.siskelfilmcenter.org CHICAGO PREMIERE! 2017, Alison Chernick, USA, 80 min. “Briskly entertaining…Good music and good company make ITZHAK a pleasure.” —Dennis Harvey, Variety. ITZHAK is a warm and intimate portrait of Itzhak Perlman, widely considered the greatest violinist of his time. We learn of the Israeli- born virtuoso’s battle with polio, and we see his breakthrough performance on the Ed Sullivan Show at age thirteen. But ITZHAK is less a biographical look-back than a present-tense chance to hang out with the effervescent and still very active 72-year-old as he zips around Manhattan in his motorized wheelchair. In English and Hebrew with English subtitles. DCP digital. (MR) April 6—12 Fri., 4/6 at 2 pm and 6:15 pm; Sat., 4/7 at 3:15 pm and 7:45 pm; Sun., 4/8 at 3 pm; Mon., 4/9 at 6 pm; Tue., 4/10 at 8:15 pm; ITZHAK Wed., 4/11 at 6:15 pm; Thu., 4/12 at 8:15 pm CHICAGO PREMIERE! April 6—12 Fri., 4/6 at 1:45 pm and 6 pm; Sat., 4/7 at 8 pm; Sun., 4/8 at 2:45 pm; Mon., 4/9 at 7:45 pm; Tue., 4/10 at 6 pm; Wed., 4/11 at 8 pm; Thu., 4/12 at 6 pm Outside2017, Lynn Shelton, USA, 109 min. -

Debatni Program 27. Festivala Evropskog Filma

POKROVITELJI PATRONS ap Vojvodina Republika Srbija pokrAjiNSKI SekretArijAT MINISTARStvo KUltUre I ZA KUltURU I JAVNO informisanjA informisanjE otvoreNI UNiverZitet GRAD SUBotiCA SUBotiCA OSNIVAČ FESTIVALA ORGANIZATOR I IZVRŠNI PRODUCENT FOUNDER OF THE FESTIVAL ORGANISER AND EXECUTIVE PRODUCER Septembar 12-18 2020 palicfilmfestival.com PALIĆ 2020 PALIĆ 2020 Neizvesnost prati naš Festival od njegovog nastanka. retke su godine kada smo Uncertainty has been following our Festival from its beginning. Rarely have we ever had Festivalu mogli u potpunosti da se posvetimo i ne mislimo šta će ga ugroziti, odnosno, a chance to dedicate ourselves to the Festival itself, without thinking about what could da li će ga uopšte biti. jeopardize it or would it be held at all. Početkom 90-tih, kada smo osnovali Festival, to nisu bili samo problemi koji su normalni kada uspostavljate nešto novo,već i činjenica da je on osnovan u vreme sankcija.Izašli In the early 90’s, when we started the Festival, those were not normal establishing problems, smo iz sankcija 1995. Godine, „videli svetlo na kraju tunela“, ali te godine Festival nije but we dealt with international sanctions. In 1995 we were free of sanctions, seeing the light održan, jer nije bilo dovoljno sredstava. Na samom kraju te dekade dočekala nas je at the end of tunnel, but the Festival wasn’t held because of the lack of funds. At the end of agresija NATO Alijanse i bombardovanje…Ipaksmo te 1999.godine,uprkos svemu, that decade in 1999 we faced NATO bombing… But despite aggression we organized, as we održali, kako smo ga nazvali, Festival kontinuiteta.Trajao je samo tokom jednog called it, Festival of Continuity. -

2015 Programme

Queensland Film Festival is Made possible by the support of Our Partners Major Partners Contents A Note From Our Patron .................................................................................................................4 Co-directors’ Statement.................................................................................................................5 Venue Partners Films The Colour of Pomegranates ........................................................................................................6 The Duke of Burgundy ....................................................................................................................7 Eight ..................................................................................................................................................8 Episode of the Sea ..........................................................................................................................9 Media Partners The Forbidden Room ....................................................................................................................10 Jauja ...............................................................................................................................................11 Jealousy .........................................................................................................................................12 Magic Miles ....................................................................................................................................13