Divide and Rule: State Penetration in Hazarajat (Afghanistan) from the Monarchy to the Taliban

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

People of Ghazni

Program for Culture & Conflict Studies www.nps.edu/programs/ccs/ Province: Zabul April 13, 2009 Governor: Mohammad Ashraf Nasseri Provincial Police Chief: Colonel Mohammed Yaqoub Population Estimate: Urban: 9,200 Rural: 239,9001 249,100 Area in Square Kilometers: 17,343 Capital: Qalat (formerly known as Qalat-i Ghilzai) Names of Districts: Arghandab, Baghar, Day Chopan, Jaldak, Kaker, Mizan, Now Bahar, Qalat, Shah Joy, Shamulza’i, Shinkay Composition of Population: Ethnic Groups: Religions: Tribal Groups: Tokhi & Hotaki Majority Pashtun Predominately Sunni Ghilzais, Noorzai &Panjpai Islam Durranis Occupation of Population Major: Agriculture (including opium), labor, Minor: Trade, manufacturing, animal husbandry smuggling Crops/Farming/ Poppy, wheat, maize, barley, almonds, Sheep, goat, cow, camel, donkey Livestock:2 grapes, apricots, potato, watermelon, cumin Language: Overwhelmingly Pashtu, although some Dari can be found, mostly as a second language Literacy Rate Total: 1% (1% male, a few younger females)3 Number of Educational Primary & Secondary: 168 (98% all Colleges/Universities: None, although Institutions: 80 male) 35272 student (99% male), some training centers do exist for 866 teachers (97% male) vocational skills Number of Security Incidents, January: 3 May: 6 September: 7 2007:774 February: 4 June: 8 October: 7 March: 3 July: 8 November: 10 April: 11 August: 5 December: 5 Poppy (Opium) Cultivation: 2006: 3,210ha 2007: 1,611ha NGOs Active in Province: Ibn Sina, Vara, ADA, Red Crescent, CADG Total PRT Projects: 40 Other Aid Projects: 573 Planned Cost: $8,283,665 Planned Cost: $19,983,250 Total Spent: $2,997,860 Total Spent: $1,880,920 Transportation: 1 Airstrip in Primary Roads: The ring road from Ghazni to Kandahar passes through Qalat and Qalat “PRT Air” – 2 flights Shah Joy. -

Alizai Durrani Pashtun

Program for Culture & Conflict Studies www.nps.edu/programs/ccs Khugiani Clan Durrani Pashtun Pashtun Duranni Panjpai / Panjpal / Panjpao Khugiani (Click Blue box to continue to next segment.) Reference: Courage Services Inc., Tribal Hierarchy & Dictionary of Afghanistan: A Reference Aid for Analysts, (February 2007). Adamec, Ludwig, Historical and Political Gazetteer of Afghanistan, Vol. 6, 1985. Program for Culture & Conflict Studies www.nps.edu/programs/ccs Khugiani Clan Durrani Pashtuns Khugiani Gulbaz Khyrbun / Karbun Khabast Sherzad Kharbun / Khairbun Wazir / Vaziri / Laili (Click Blue box to continue to next segment.) Kharai Najibi Reference: Courage Services Inc., Tribal Hierarchy & Dictionary of Afghanistan: A Reference Aid for Analysts, (February 2007). Adamec, Ludwig, Historical and Political Gazetteer of Afghanistan, Vol. 6, 1985. Program for Culture & Conflict Studies www.nps.edu/programs/ccs Khyrbun / Karbun Khugiani Clan Khyrbun / Karbun Karai/ Garai/ Karani Najibi Ghundi Mukar Ali Mando Hamza Paria Api Masto Jaji / Jagi Tori Daulat Khidar Motik Reference: Courage Services Inc., Tribal Hierarchy & Dictionary of Afghanistan: A Reference Aid for Analysts, (February 2007). Adamec, Ludwig, Historical and Political Gazetteer of Afghanistan, Vol. 6, 1985. Program for Culture & Conflict Studies www.nps.edu/programs/ccs Sherzad Khugiani Clan Sherzad Dopai Marki Khodi Panjpai Lughmani Shadi Mama Reference: Courage Services Inc., Tribal Hierarchy & Dictionary of Afghanistan: A Reference Aid for Analysts, (February 2007). Adamec, Ludwig, Historical and Political Gazetteer of Afghanistan, Vol. 6, 1985. Program for Culture & Conflict Studies www.nps.edu/programs/ccs Wazir / Vaziri / Laili Khugiani Clan Wazir / Vaziri / Laili Motik / Motki Sarki / Sirki Ahmad / Ahmad Khel Pira Khel Agam / Agam Khel Nani / Nani Khel Kanga Piro Barak Rani / Rani Khel Khojak Taraki Bibo Khozeh Khel Reference: Courage Services Inc., Tribal Hierarchy & Dictionary of Afghanistan: A Reference Aid for Analysts, (February 2007). -

AFGHANISTAN - Base Map KYRGYZSTAN

AFGHANISTAN - Base map KYRGYZSTAN CHINA ± UZBEKISTAN Darwaz !( !( Darwaz-e-balla Shaki !( Kof Ab !( Khwahan TAJIKISTAN !( Yangi Shighnan Khamyab Yawan!( !( !( Shor Khwaja Qala !( TURKMENISTAN Qarqin !( Chah Ab !( Kohestan !( Tepa Bahwddin!( !( !( Emam !( Shahr-e-buzorg Hayratan Darqad Yaftal-e-sufla!( !( !( !( Saheb Mingajik Mardyan Dawlat !( Dasht-e-archi!( Faiz Abad Andkhoy Kaldar !( !( Argo !( Qaram (1) (1) Abad Qala-e-zal Khwaja Ghar !( Rostaq !( Khash Aryan!( (1) (2)!( !( !( Fayz !( (1) !( !( !( Wakhan !( Khan-e-char Char !( Baharak (1) !( LEGEND Qol!( !( !( Jorm !( Bagh Khanaqa !( Abad Bulak Char Baharak Kishim!( !( Teer Qorghan !( Aqcha!( !( Taloqan !( Khwaja Balkh!( !( Mazar-e-sharif Darah !( BADAKHSHAN Garan Eshkashem )"" !( Kunduz!( !( Capital Do Koh Deh !(Dadi !( !( Baba Yadgar Khulm !( !( Kalafgan !( Shiberghan KUNDUZ Ali Khan Bangi Chal!( Zebak Marmol !( !( Farkhar Yamgan !( Admin 1 capital BALKH Hazrat-e-!( Abad (2) !( Abad (2) !( !( Shirin !( !( Dowlatabad !( Sholgareh!( Char Sultan !( !( TAKHAR Mir Kan Admin 2 capital Tagab !( Sar-e-pul Kent Samangan (aybak) Burka Khwaja!( Dahi Warsaj Tawakuli Keshendeh (1) Baghlan-e-jadid !( !( !( Koran Wa International boundary Sabzposh !( Sozma !( Yahya Mussa !( Sayad !( !( Nahrin !( Monjan !( !( Awlad Darah Khuram Wa Sarbagh !( !( Jammu Kashmir Almar Maymana Qala Zari !( Pul-e- Khumri !( Murad Shahr !( !( (darz !( Sang(san)charak!( !( !( Suf-e- (2) !( Dahana-e-ghory Khowst Wa Fereng !( !( Ab) Gosfandi Way Payin Deh Line of control Ghormach Bil Kohestanat BAGHLAN Bala !( Qaysar !( Balaq -

Role of English in Afghan Language Policy Planning with Its Impact on National Integration (2001-2010)

ROLE OF ENGLISH IN AFGHAN LANGUAGE POLICY PLANNING WITH ITS IMPACT ON NATIONAL INTEGRATION (2001-2010) By AYAZ AHMAD Area Study Centre (Russia, China & Central Asia) UNIVERSITY OF PESHAWAR (DECEMBER 2016) ROLE OF ENGLISH IN AFGHAN LANGUAGE POLICY PLANNING WITH ITS IMPACT ON NATIONAL INTEGRATION (2001-2010) By AYAZ AHMAD A dissertation submitted to the University of Peshawar in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (DECEMBER 2016) i AUTHOR’S DECLARATION I, Mr. Ayaz Ahmad hereby state that my PhD thesis titled “Role of English in Afghan Language Policy Planning with its Impact on National Integration (2001-2010)” is my own work and has not been submitted previously by me for taking any degree from this University of Peshawar or anywhere else in the country/world. At any time if my statement is found to be incorrect even after my graduation the University has the right to withdraw my PhD degree. AYAZ AHMAD Date: December 2016 ii PLAGIARISM UNDERTAKING I solemnly declare that research work presented in the thesis titled “Role of English in Afghan Language Policy Planning with its Impact on National Integration (2001-2010)” is solely my research work with no significant contribution from any other person. Small contribution/help wherever taken has been duly acknowledged and that complete thesis has been written by me. I understand the zero tolerance policy of the Higher Education Commission (HEC) and University of Peshawar towards plagiarism. Therefore I as an Author of the above-titled thesis declare that no portion of my thesis has been plagiarized and any material used as a reference is properly referred/cited. -

The Kingdom of Afghanistan: a Historical Sketch George Passman Tate

University of Nebraska Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Books in English Digitized Books 1-1-1911 The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch George Passman Tate Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/afghanuno Part of the History Commons, and the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Tate, George Passman The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch, with an introductory note by Sir Henry Mortimer Durand. Bombay: "Times of India" Offices, 1911. 224 p., maps This Monograph is brought to you for free and open access by the Digitized Books at DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Books in English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tate, G,P. The kfn&ean sf Af&mistan, DATE DUE I Mil 7 (7'8 DEDICATED, BY PERMISSION, HIS EXCELLENCY BARON HARDINGE OF PENSHURST. VICEROY AND GOVERNOR-GENERAL OF INDIA, .a- . (/. BY m HIS OBEDIENT, SERVANT THE AUTHOR. il.IEmtev 01 the Asiniic Society, Be?zg-nl, S?~rueyof I~din. dafhor of 'I Seisinqz : A Menzoir on the FJisio~y,Topo~rcrphj~, A7zliquiiies, (112d Peo$Ie of the Cozi?zt~y''; The F/.o?zlic7,.~ of Baluchisia'nn : Travels on ihe Border.? of Pe~szk n?zd Akhnnistnn " ; " ICalnf : A lMe??zoir on t7ze Cozl7~try and Fnrrzily of the Ahntadsai Khn7zs of Iinlnt" ; 4 ec. \ViTkI AN INrPR<dl>kJCTOl2Y NO'FE PRINTED BY BENNETT COLEMAN & Co., Xc. PUBLISHED AT THE " TIMES OF INDIA" OFFTCES, BOMBAY & C.1LCUTT-4, LONDON AGENCY : gg, SI-IOE LANE, E.C. -

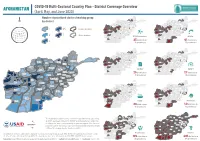

AFGHANISTAN COVID-19 Multi-Sectoral Country Plan - District Coverage Overview (April, May, and June 2020) Number of Prioritized Clusters/Working Group

AFGHANISTAN COVID-19 Multi-Sectoral Country Plan - District Coverage Overview (April, May, and June 2020) Number of prioritized clusters/working group Badakhshan Badakhshan Jawzjan Kunduz Jawzjan Kunduz Balkh Balkh N by district Takhar Takhar Faryab Faryab Samangan Samangan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Panjsher Nuristan Panjsher Nuristan Badghis Parwan Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Laghman Laghman Kabul Kabul Maidan Wardak Maidan Wardak Ghor Nangarhar Ghor Nangarhar 1 4-5 province boundary Logar Logar Hirat Daykundi Hirat Daykundi Paktya Paktya Ghazni Khost Ghazni Khost Uruzgan Uruzgan Farah Farah Paktika Paktika 2 7 district boundary Zabul Zabul DTM Prioritized: WASH: Hilmand Hilmand Kandahar Kandahar Nimroz Nimroz 25 districts in 41 districts in 3 10 provinces 13 provinces Badakhshan Badakhshan Jawzjan Kunduz Jawzjan Kunduz Balkh Balkh Takhar Takhar Faryab Faryab Samangan Samangan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Panjsher Nuristan Panjsher Nuristan Badghis Parwan Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Laghman Laghman Kabul Kabul Maidan Wardak Maidan Wardak Badakhshan Ghor Nangarhar Ghor Nangarhar Jawzjan Logar Logar Kunduz Hirat Daykundi Hirat Daykundi Balkh Paktya Paktya Takhar Ghazni Khost Ghazni Khost Uruzgan Uruzgan Farah Farah Paktika Paktika Faryab Zabul Zabul Samangan Baghlan Hilmand EiEWG: Hilmand ESNFI: Sar-e-Pul Kandahar Kandahar Nimroz Nimroz Panjsher Nuristan 25 districts in 27 districts in Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar 10 provinces 12 provinces Laghman Kabul Maidan -

The Taliban Conundrum

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 22, Issue 1, Ver. 2 (January 2017) PP 21-26 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org The Taliban Conundrum Mudassir Fatah Research Scholar, Department of Political Science, Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi-110025 Abstract: - National interests do guide the foreign policy of a nation. A state can go to any extent for fulfilling the same. Same had been reflected in the proxy wars played in Afghanistan. It is these national interests of some states which are responsible for the rise of the Taliban movement. Although there are some internal factors who also played a crucial role while giving birth to the Taliban movement, but these internal circumstances were created so to be the part of the conflict which eventually gave rise to the Taliban movement. The cold war power politics played in the poor and a weak nation like Afghanistan resulted in such a force which is still haunting the millions in the world. Keywords: - Afghanistan, Civil War, Peace, Power Politics, Taliban. I. INTRODUCTION Taliban is the plural of ‘Talib’, which has its origin from Arabic. The literal meaning of Talib is seeking something for one’s own self. The word Talib has been derived from the word ‘Talab’ which means desire. The word Taliban, in Pushto, generally denotes, students studying in Deeni Madaris (religious schools).1 These Deeni Madaris were (mostly) Deobandi schools in Pakistan. II. RISE OF THE TALIBAN MOVEMENT-INTERNAL FACTORS After the Soviet departure, the factor which united all the Mujahedeen groups against the common enemy, no longer existed, which resulted into chaos, looting and finally civil war. -

Afghan Women at the Crossroads: Agents of Peace—Or Its Victims?

AFGHAN WOMEN AT THE CROSSROADS: AGENTS OF PEACE—OR ITS VICTIMS? ORZALA ASHRAF NEMAT A CENTURY FOUNDATION REPORT The Century Foundation Headquarters: 41 East 70th Street, New York, New York 10021 D 212.535.4441 D.C.: 1333 H Street, N.W., 10th floor, Washington, D.C. 20005 D 202.387.0400 THE CENTURY FOUNDATION PROJECT ON AFGHANISTAN IN ITS REGIONAL AND MULTILATERAL DIMENSIONS This paper is one of a series commissioned by The Century Foundation as part of its project on Afghanistan in its regional and multilateral dimensions. This initiative is examining ways in which the international community may take greater collective responsibility for effectively assisting Afghanistan’s transition from a war-ridden failed state to a fragile but reasonably peaceful one. The program adds an internationalist and multilateral lens to the policy debate on Afghanistan both in the United States and globally, engaging the representatives of governments, international nongovernmental organizations, and the United Nations in the exploration of policy options toward Afghanistan and the other states in the region. At the center of the project is a task force of American and international figures who have had significant governmental, nongovernmental, or UN experience in the region, co-chaired by Lakhdar Brahimi and Thomas Pickering, respectively former UN special representative for Afghanistan and former U.S. undersecretary of state for political affairs. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors. Nothing written here is to be construed as necessarily reflecting the views of The Century Foundation or as an attempt to aid or hinder the passage of any bill before Congress. -

Nation Building Process in Afghanistan Ziaulhaq Rashidi1, Dr

Saudi Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Abbreviated Key Title: Saudi J Humanities Soc Sci ISSN 2415-6256 (Print) | ISSN 2415-6248 (Online) Scholars Middle East Publishers, Dubai, United Arab Emirates Journal homepage: http://scholarsmepub.com/sjhss/ Original Research Article Nation Building Process in Afghanistan Ziaulhaq Rashidi1, Dr. Gülay Uğur Göksel2 1M.A Student of Political Science and International Relations Program 2Assistant Professor, Istanbul Aydin University, Istanbul, Turkey *Corresponding author: Ziaulhaq Rashidi | Received: 04.04.2019 | Accepted: 13.04.2019 | Published: 30.04.2019 DOI:10.21276/sjhss.2019.4.4.9 Abstract In recent times, a number of countries faced major cracks and divisions (religious, ethnical and geographical) with less than a decade war/instability but with regards to over four decades of wars and instabilities, the united and indivisible Afghanistan face researchers and social scientists with valid questions that what is the reason behind this unity and where to seek the roots of Afghan national unity, despite some minor problems and ethnic cracks cannot be ignored?. Most of the available studies on nation building process or Afghan nationalism have covered the nation building efforts from early 20th century and very limited works are available (mostly local narratives) had touched upon the nation building efforts prior to the 20th. This study goes beyond and examine major struggles aimed nation building along with the modernization of state in Afghanistan starting from late 19th century. Reforms predominantly the language (Afghani/Pashtu) and role of shared medium of communication will be deliberated. In addition, we will talk how the formation of strong centralized government empowered the state to initiate social harmony though the demographic and geographic oriented (north-south) resettlement programs in 1880s and how does it contributed to the nation building process. -

Produced by the Human Security Centre Lead Author

1 Human Security Centre – Written evidence (AFG0019) Produced by the Human Security Centre Lead Author: Simon Schofield, Senior Fellow, In consultation with Rohullah Yakobi, Associate Fellow 2 1 Table of Contents 2. Executive Summary .............................................................................5 3. What is the Human Security Centre?.....................................................10 4. Geopolitics and National Interests and Agendas......................................11 Islamic Republic of Pakistan ...................................................................11 Historical Context...............................................................................11 Pakistan’s Strategy.............................................................................12 Support for the Taliban .......................................................................13 Afghanistan as a terrorist training camp ................................................16 Role of military aid .............................................................................17 Economic interests .............................................................................19 Conclusion – Pakistan .........................................................................19 Islamic Republic of Iran .........................................................................20 Historical context ...............................................................................20 Iranian Strategy ................................................................................23 -

Hazara Tribe Next Slide Click Dark Blue Boxes to Advance to the Respective Tribe Or Clan

Program for Culture & Conflict Studies www.nps.edu/programs/ccs Advance to Hazara Tribe next slide Click dark blue boxes to advance to the respective tribe or clan. Hazara Abak / Abaka Besud / Behsud / Basuti Allakah Bolgor Allaudin Bubak Bacha Shadi Chagai Baighazi Chahar Dasta / Urni Baiya / Baiyah Chula Kur Barat Dahla / Dai La Barbari Dai Barka Begal Dai Chopo Beguji / Bai Guji Dai Dehqo / Dehqan Reference: Courage Services Inc., Tribal Hierarchy & Dictionary of Afghanistan: A Reference Aid for Analysts, (February 2007). Adamec. Vol 6; Hazaras Poladi, 37; EE Bacon, P.20-31 Topography, Ethnology, Resources & History of Afghanistan. Part II. Calcutta:, 1871 (p. 628). Program for Culture & Conflict Studies www.nps.edu/programs/ccs Return to Advance to First slide Hazara Tribe next slide Hazara Dai Kundi / Deh Kundi Dayah Dai Mardah / Dahmarda Dayu Dai Mirak Deh Zengi Dai Mirkasha Di Meri / Dai Meri Dai Qozi Di Mirlas / Dai Mirlas Dai Zangi / Deh Zangi Di Nuri / Dai Nuri Daltamur Dinyari /Dinyar Damarda Dosti Darghun Faoladi Dastam Gadi / Gadai Reference: Courage Services Inc., Tribal Hierarchy & Dictionary of Afghanistan: A Reference Aid for Analysts, (February 2007). Adamec. Vol 6; Hazaras Poladi, 37; EE Bacon, P.20-31 Topography, Ethnology, Resources & History of Afghanistan. Part II. Calcutta:, 1871 (p. 628). Program for Culture & Conflict Studies www.nps.edu/programs/ccs Return to Advance to First slide Hazara Tribe next slide Hazara Gangsu Jaokar Garhi Kadelan Gavi / Gawi Kaghai Ghaznichi Kala Gudar Kala Nao Habash Kalak Hasht Khwaja Kalanzai Ihsanbaka Kalta Jaghatu Kamarda Jaghuri / Jaghori Kara Mali Reference: Courage Services Inc., Tribal Hierarchy & Dictionary of Afghanistan: A Reference Aid for Analysts, (February 2007). -

19 October 2020 "Generated on Refers to the Date on Which the User Accessed the List and Not the Last Date of Substantive Update to the List

Res. 1988 (2011) List The List established and maintained pursuant to Security Council res. 1988 (2011) Generated on: 19 October 2020 "Generated on refers to the date on which the user accessed the list and not the last date of substantive update to the list. Information on the substantive list updates are provided on the Council / Committee’s website." Composition of the List The list consists of the two sections specified below: A. Individuals B. Entities and other groups Information about de-listing may be found at: https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/ombudsperson (for res. 1267) https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/sanctions/delisting (for other Committees) https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/content/2231/list (for res. 2231) A. Individuals TAi.155 Name: 1: ABDUL AZIZ 2: ABBASIN 3: na 4: na ﻋﺒﺪ اﻟﻌﺰﻳﺰ ﻋﺒﺎﺳﯿﻦ :(Name (original script Title: na Designation: na DOB: 1969 POB: Sheykhan Village, Pirkowti Area, Orgun District, Paktika Province, Afghanistan Good quality a.k.a.: Abdul Aziz Mahsud Low quality a.k.a.: na Nationality: na Passport no: na National identification no: na Address: na Listed on: 4 Oct. 2011 (amended on 22 Apr. 2013) Other information: Key commander in the Haqqani Network (TAe.012) under Sirajuddin Jallaloudine Haqqani (TAi.144). Taliban Shadow Governor for Orgun District, Paktika Province as of early 2010. Operated a training camp for non- Afghan fighters in Paktika Province. Has been involved in the transport of weapons to Afghanistan. INTERPOL- UN Security Council Special Notice web link: https://www.interpol.int/en/How-we-work/Notices/View-UN-Notices- Individuals click here TAi.121 Name: 1: AZIZIRAHMAN 2: ABDUL AHAD 3: na 4: na ﻋﺰﯾﺰ اﻟﺮﺣﻤﺎن ﻋﺒﺪ اﻻﺣﺪ :(Name (original script Title: Mr Designation: Third Secretary, Taliban Embassy, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates DOB: 1972 POB: Shega District, Kandahar Province, Afghanistan Good quality a.k.a.: na Low quality a.k.a.: na Nationality: Afghanistan Passport no: na National identification no: Afghan national identification card (tazkira) number 44323 na Address: na Listed on: 25 Jan.