Contested Border and Division of Families in Kashmir: Contextualizing the Ordeal of the Kargil Women

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Mohd Hussain S/O Mohd Ibrahim R/O Dargoo Shakar Chiktan 01.02

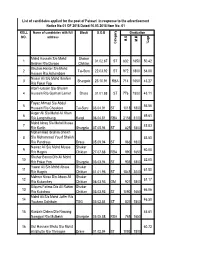

List of candidates applied for the post of Patwari in response to the advertisement Notice No:01 OF 2018 Dated:10.03.2018 Item No: 01 ROLL Name of candidates with full Block D.O.B Graduation NO. address M.O M.M %age Category Category Mohd Hussain S/o Mohd Shakar 1 01.02.87 ST 832 1650 50.42 Ibrahim R/o Dargoo Chiktan Ghulam Haider S/o Mohd 2 Tai-Suru 22.03.92 ST 972 1800 54.00 Hassan R/o Achambore Nissar Ali S/o Mohd Ibrahim 3 Shargole 23.10.91 RBA 714 1650 43.27 R/o Fokar Foo Altaf Hussain S/o Ghulam 4 Hussain R/o Goshan Lamar Drass 01.01.88 ST 776 1800 43.11 Fayaz Ahmad S/o Abdul 5 56.56 Hussain R/o Choskore Tai-Suru 03.04.91 ST 1018 1800 Asger Ali S/o Mohd Ali Khan 6 69.61 R/o Longmithang Kargil 06.04.81 RBA 2158 3100 Mohd Ishaq S/o Mohd Mussa 7 45.83 R/o Karith Shargole 07.05.94 ST 825 1800 Mohammad Ibrahim Sheikh 8 S/o Mohammad Yousf Sheikh 53.50 R/o Pandrass Drass 05.09.94 ST 963 1800 Nawaz Ali S/o Mohd Mussa Shakar 9 60.00 R/o Hagnis Chiktan 27.07.88 RBA 990 1650 Shahar Banoo D/o Ali Mohd 10 52.00 R/o Fokar Foo Shargole 03.03.94 ST 936 1800 Yawar Ali S/o Mohd Abass Shakar 11 61.50 R/o Hagnis Chiktan 01.01.96 ST 1845 3000 Mehrun Nissa D/o Abass Ali Shakar 12 51.17 R/o Kukarchey Chiktan 06.03.93 OM 921 1800 Bilques Fatima D/o Ali Rahim Shakar 13 66.06 R/o Kukshow Chiktan 03.03.93 ST 1090 1650 Mohd Ali S/o Mohd Jaffer R/o 14 46.50 Youkma Saliskote TSG 03.02.84 ST 837 1800 15 Kunzais Dolma D/o Nawang 46.61 Namgyal R/o Mulbekh Shargole 05.05.88 RBA 769 1650 16 Gul Hasnain Bhuto S/o Mohd 60.72 Ali Bhutto R/o Throngos Drass 01.02.94 ST -

Green Market Capsule

GREEN MARKET CAPSULE Issue no: 73|February' 2021 TPTCL'S E-NEWSLETTER -2017-2017 Tata Power Trading Company Limited (TPTCL) Contents: 1. Energy New…………….....01-20 2. Source wise break up…....20-21 3. REC Inventory………………..21 Power News Maharashtra's New Renewable Energy Policy to attract Rs 75,000-cr investments New Delhi, Jan 28 (PTI) Maharashtra's New Renewable Energy Policy will attract Rs 75,000-crore investments, said the state's Power and New & Renewable Energy Minister Nitin Raut on Thursday. "Nitin Raut, Minister for Power and New & Renewable Energy, Government of Maharashtra, today while highlighting the Maharashtra's New Renewable Energy Policy said that the policy aims to promote public and private sector participation and will attract an investment of Rs 75,000 crore in power and allied sectors," FICCI said in a statement on Thursday. Addressing an interactive session with the CEOs of renewable energy and power companies organised by FICCI, Raut said the policy aims to implement 17,000 MW of renewable power projects in the next 5 years. It is expected to create direct and indirect employment for one lakh people, along with giving priority to hybrid power projects. "In line with the Paris Agreement, the Government of Maharashtra is committed to achieving 40 per cent electricity generation from renewable energy sources by 2030," Raut added, as per the statement. Maharashtra Principal Secretary (Energy) Asim Gupta addressed various concerns of the industry related to payment security, transmission, hybrid policy, open access, rooftop solar, and tenders for greenfield renewable energy projects, phasing out old inefficient plants. -

Indian Railways Plans for DFC, Multomodal & International Cargo

Indian Railways Plans for DFC, Multomodal & International Rail Cargo Transportation Sanjiv Garg Additional Member Railway Board, India September 28, 2018 DEDICATED FREIGHT CORRIDORS Golden Quadrilateral & Its Diagonals High Density Corridor (Golden Quadrilateral DELHI + Diagonals) 16% of route KOLKATTA Km carries more than MUMBAI 52% of passenger & 58 % of freight CHENNAI www.dfccil.gov.in CONCEPT PLAN OF DEDICATED FREIGHT CORRIDOR NETWORK LUDHIANA DELHI KOLKATA MUMBAI Sanctioned projects VIJAYAWADA VASCO Unsanctioned projects CHENNAI www.dfccil.gov.in Eastern Corridor (1856 km) Khurja -Bhaupur (343 km) Bhaupur-Mughalsarai (402 km) Khurja-Ludhiana (400 km) Khurja-Dadri (47 km) Western Corridor (1504 km) Mughalsarai-Sonnagar (126 km) Rewari-Vadodara (947 km) Sonnagar-Dankuni (538 km) Vadodara-JNPT ( 430 km) Rewari-Dadri (127 km) 5 Introduction Feb 2006 CCEA approved feasibility reports of DFC. Nov 2007 CCEA gave ‘in principle’ approval with authorization to incur expenditure on preliminary and preparatory works. Feb 2008 CCEA approved undertaking work & extension of EDFC from Sonnagar to Dankuni. Directed MoR to finalise financing and implementation mechanisms Sept 2009 Cabinet approved JICA loan for WDFC along with STEP loan conditionalities Mar 2010 JICA Loan Agreement for JPY 90 billion (Rs. 5100 crores) signed for WDFC-I. Oct 2011 Loan Agreement with World Bank for USD 975 Million (Rs. 5850 crores) signed for EDFC -1 (Khurja-Bhaupur). Mar 2013 JICA Loan Agreement for WDFC Phase-II: 1st Tranche amounting JPY 136 billion (Rs. 7750 crores) signed. Dec 2014 Loan Agreement with World Bank loan of USD 1100 million signed (EDFC-2). June 2015 Cost estimate of Rs. 81,459 Crores approved by CCEA. -

Senate Secretariat ————— “Questions

(104th Session) SENATE SECRETARIAT ————— “QUESTIONS FOR ORAL ANSWERS AND THEIR REPLIES” to be asked at a sitting of the Senate to be held on Wednesday, the 21st May, 2014 DEFERRED QUESTIONS (Questions Nos, 94, 95, 103, 108, 111, 112, 140, 142, 148, 152, 153, 156, 157, 163,164, 165, and 169 Deferred on 23rd April, 2014 (103rd Session) 94. (Def) *Mr. Muhammad Talha Mehmood: (Notice received on 01-01-2014 at 09:10 am) Will the Minister for Railways be pleased to state: (a) the average time of delay in departure and arrival of trains recorded during the last two years; and (b) the steps taken / being taken by the Government for departure and arrival of trains on scheduled time? Khawaja Saad Rafique: (a) Average time of delay per train during the last two years (2012 and 2013) is as under.— Year Average delay per train 2012 2 hour and 30 minutes 2013 1 hours and 30 minutes (b) The following steps have been taken for running trains on scheduled timings. (i) Procurment of 58 new locomotives. (ii) Rehablitation of 27 locomotives. (iii) Manufacturing of 202 new design modern passenger coaches. (iv) Doubling of track from Lodhran to Raiwind. (v) Installation of computer based signaling equipment on Shahdara Bagh – Lodhran section and Bin Qasim to Mirpur Mathelo sections. (vi) Footplat inspections by Assistant and Divisional Officers in their jurisdictions. (vii) Improved track maintenance to increase speed of trains. (viii) Effective repair and maintenance of locomotives and coaches. (ix) Improved washing lines facilities. (x) HSD Oil reserve was limited for two days which has been enhanced to 15 days to streamline the operations of trains. -

Speech of Shri Lalu Prasad Introducing the Railway Budget 2006-07 on 24Th February 2006

Speech of Shri Lalu Prasad Introducing the Railway Budget 2006-07 On 24th February 2006 1. Mr. Speaker Sir, I rise to present the Budget Estimates 2006-07 for the Indian Railways at a point in time when, there has been a historical turn around in the financial situation of the Indian Railways. Our fund balances have grown to Rs. 11,000 cr and our internal generation, before dividend has also reached a historic level of Rs. 11,000 cr. With this unprecedented achievement, we are striding to realize the Hon’ble Prime Minister’s dream of making Indian Railways the premier railway of the world. Sir, this is the same Indian Railways which, in 2001 had deferred dividend payment, whose fund balances had reduced to just Rs. 350 cr and about which experts had started saying that it is enmeshed a terminal debt trap. You might term this a miracle, but I was confident that : “Mere zunu ka natija zaroor niklega, isee siaah samandar se noor niklega.” 2. Sir, the whole nation can see today that track is the same, railwaymen are the same but the image of Indian Railways is aglow. This has been the result of the acumen, devotion and determination of lakhs of railwaymen. Sir, the general perception so far has been that Railways’ finances cannot be improved without increasing second class passenger fares. But my approach is entirely different. In my view, improvements can only be brought about by raising the quality of services, reducing unit costs and sharing the resultant gain with customers. Therefore, instead of following the beaten path, we decided to tread a new one. -

Sub: Agenda Items for Next PNM Meeting of AIRF with Railway Board

Sub: Agenda items for next PNM Meeting of AIRF with Railway Board Item No.01/2016 Sub: Implementation of the report of the E.D. Committee regarding granting Zonal Railway status to Metro Railway Kolkata Ref.: AIRF‟s letter No.AIRF/Sub-Committee 73 dated May 5, 2016 It may be recalled that, Metro Railway Kolkata was declared 17th Railway Zone by the Ministry of Railways w.e.f. 22.10.2010. Accordingly, one committee, comprising of the Executive Directors, was constituted by the Railway Board, vide their letter No.ERB-1/2010/23/42 dated 28.12.2010, to work out the modalities for revision of status of Metro Railway Kolkata as Zonal Railway. The said committee submitted its report in July 2011, which was duly accepted by the Railway Board in June 2012. But it is quite unfortunate that, in spite of consistent persuasions made by our Metro Railway Kolkata affiliate - Metro Railwaymen’s Union Kolkata as also by the Metro Railway Kolkata Administration, recommendations of the above cited committee are still pending, for implementation, in Rail Bhawan. As a result, distribution of Group `A’, `B’ Cadre, creation of Division for monitoring operation and maintenance works, have not been done as yet. Only one recommendation of this committee, i.e. recognition of the union through secret ballot, has been implemented. As a result of inordinate delay in implementing the report of the aforementioned committee, there is serious unrest and discontentment among the staff of Metro Railway, Kolkata. AIRF, therefore, urges that, recommendations of the aforementioned committee be implemented in letter and spirit without further delay. -

TOP 100 Expected GK Questions on Indian Railways | Specially for RRB NTPC 2019

TOP 100 Expected GK Questions on Indian Railways | Specially for RRB NTPC 2019 1) What is the rank of Indian Railways in the world in terms a) Himsagar Express of size of the railroad network? b) Silchar Superfast Express a) 2nd c) Navyug Express b) 5th d) Vivek Express c) 4th d) 10th Answer: d) Vivek Express covers the longest train route in India. It Answer: c) originates in northern Assam and goes all the way to the Indian Railways (IR) is India's national railway system southern tip of India to Kanyakumari. It has the running time operated by the Ministry of Railways. It manages the fourth of 80 hours and 15 minutes and the distance covered is largest railway network in the world by size, with 121,407 4,233 kilometres. kilometres of total track over a 67,368-kilometre route. 5) Which express is the currently operational trans-border 2) Which is India’s first passenger train that ran between train between India and Pakistan? Bombay and Thane in 1853? a) Thar Express a) Great Indian Peninsula Railway b) Akbar Express b) Central Railway c) Samjhauta Express c) Bombay Baroda Railway d) Both a and c d) Mumbai Suburban Railway Answer: d) Answer: a) Currently, there are two trans-border trains between India The Great Indian Peninsula Railway was incorporated on 1 and Pakistan. First Is Samjhauta Express that operates on August 1849 by an act of the British Parliament. It was a Delhi-Lahore Route via Attarti-Wagah Border whereas Thar predecessor of the Central Railway, whose headquarters Express links Jodhpur and Karachi via Munabao-Khokhrapar was at the Boree Bunder in Mumbai.It was India's first border crossing. -

Buffalo Conference

HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 35 Number 2 Article 19 January 2016 Buffalo Conference Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation . 2016. Buffalo Conference. HIMALAYA 35(2). Available at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol35/iss2/19 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. This Conference Report is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. her 2014 monograph Taming Tibet: South Asia Across the Disciplines Se- itself not only at the forefront of the Landscape Transformation and the Gift of ries Board Meeting. In addition to the region’s cultural politics, but also its Chinese Development. Yeh is on the ed- above-mentioned panels, lectures, geopolitics. Fredrik Barth’s Ethnic itorial board of HIMALAYA. AAS con- and themed events, the conference Groups and Boundaries signified a ma- ferences are also an excellent oppor- also featured an impressive array of jor shift in the approach to the study tunity for graduate student research film screenings and a large book fair. of ethnic groups (Fredrick Barth. and dissertation development. With [1969] 1998. Ethnic Groups and Bound- Finally, while there was strong support from the Henry Luce Founda- aries: The Social Organization of Culture representation from scholars on tion and the Social Science Research Difference. -

Abridged Tender Document

JAMMU & KASHMIR STATE POWER DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION LETTER OF INVITATION (LOI) FOR ENGAGEMENT OF CONSULTANT FOR PREPARATION OF DPR FOR FOURTEEN HEPs under PMDP-2015 Page 1 of 14 JAMMU & KASHMIR STATE POWER DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION LTD. Corporate Office: Exhibition Grounds, Opposite J&K High Court, Srinagar, J&K - 190009 Phone: 0194 – 2451665, Fax: 0194 – 2473740 Camp Office: Ashok Nagar, Satwari, Jammu, J&K - 180004 Phone: 0191 – 2430548 / 2439039 Fax: 0191-2435403. Email: [email protected]; [email protected] NIT No: JKSPDC/PMDP-2015/ Dated: - 07.02.2017 INVITATION OF BIDS The J&K State Power Development Corporation (Client) intends to implement the following 14 Hydro Projects (HEPs) under Prime Ministers Development Package-2015 (PMDP-2015) in Jammu & Kashmir State: Package (P-1) Tentative Region S. No. Project Capacity District (MW)* 1. PHAGLA 16 Jammu POONCH 2. KULAN- 21 Kashmir GANDERBAL RAMWARI 3. IGO-UPSHI 25 Leh LEH Tirisha-Thoise 25 LEH 4. Leh UPSHI 15 LEH 5. Leh 6. DRASS 24 Kargil KARGIL STAGE-I KARGIL- 24 KARGIL 7. Kargil HUNDERMAN Package (P-2) Tentative Region S. No. Project Capacity District (MW)* Page 2 of 14 1. ANS-II 25 Jammu REASI 2. DRUGDEN- 10.50 Kashmir KULGAM KULGAM 3. NIMU- 25 Leh LEH CHILLING DURBUK- 25 Leh LEH 4. SHYOK 5. SANKOO 20 Kargil KARGIL MANGDUM- 20 Kargil KARGIL 6. SANGRA BRAKOO- 20 Kargil KARGIL 7. THUINA *The capacities mentioned above are indicative. The DPR shall be made as per the actual potential of the site (while keeping in view the requirements of PHE and Irrigation Departments). To help prepare -

2.4 Pakistan Railway Assessment Pakistan Railway Assessment

2.4 Pakistan Railway Assessment Pakistan Railway Assessment Page 1 The Pakistan Railways (PR) network is comprised of 7, 791 route kilometers; 7, 346km of broad gauge, and 445 km of metre gauge. There are 633 stations in the network, 1,043km of double-track sections (in total) and 285 km of electrified sections. The section of the network Karachi-Lodhran (843km) and 193km of other short sections are double tracks, and 286km from Lahore to Khanewal is electrified. The PR network is also connected to three neighbouring countries: Iran at Taftan, India at Wagha, and Afghanistan at Chaman and Landi Kotal. The Main Line (official route name) connects the following major stations: Karachi, Multan, Lahore, Rawalpindi, and Peshawar. The existing Pakistan Railway network is shown below: Out of the 7,791 km railway network, double track sections account for 1,043km in total and electrified sections for 285km. The network is classified into 5 sections: Primary A ( 2,124km), Primary B ( 2,622km), Secondary (1,185km), Tertiary (1,416km), and Metre Gauge (439km). The double track sections are only 1,043km and mostly located in the most critical section (Karachi City – Lahore City). Most of the tracks along the PR network are laid on embankments. There are a total of 14,570 bridges of which 22 bridges are recognized as large scale bridges. Almost all of these were constructed a century ago, and now require rehabilitation work. The PR has 520 diesel locomotives, 23 electric locomotives, and 14 steam locomotives. Most of these are aging and require upgrades. The signaling system is insufficient for the current operations, and neither is the telecommunication system. -

DL ARTO KARGIL Dec2012 to Sep2015

ARTO, KARGIL(JK-07) Driving License issue Register For Period 11/12/2012 TO 30/09/2015 1 Sl No. Licence No Name of the Driver Date of Birth NT Val From -To SIGN OF AUTHORITY Date of Issue Son/Wife/Daughter of Qualification TR Val From -To Receipt Details Permanent Address Blood Group Vehicle Class Temporary Address & Sex Identification Mark 1 JK-0720130002748 MUKHTAR HUSSAIN 01/07/1984 01/01/2013 31/12/2032 01/01/2013 MOHD IBRAHIM SSLC Rs.250 /AA-8085/ UMBA SANKOO KARGIL LADAKH 194103 O+ M MCWG LMV UMBA SANKOO KARGIL LADAKH 194103 A MOLE ON NOSE. 2 JK-0720130002749 MOHD QASIM 05/02/1991 01/01/2013 31/12/2032 01/01/2013 GHULAM ABASS HSC Rs.250 /AA-8479/ SLISKOTE KARGIL LADAKH 194103 A+ M MCWG LMV SLISKOTE KARGIL LADAKH 194103 A BLACK MOLE ON RT. SHOULDER. 3 JK-0720130002750 TSEWANG YOUNTEN 03/06/1986 01/01/2013 31/12/2032 01/01/2013 SONAM ANGCHUK Post Graduation Rs.250 /AA-8480/ RANTAKSHA, ZANSKAR KARGIL LADAKH 194103 B+ M MCWG LMV RANTAKSHA, ZANSKAR KARGIL LADAKH 194103 A BLACK MOLE ON THE LEFT SIDE OF FACE. 4 JK-0720130002751 MOHD ALI 07/02/1988 01/01/2013 31/12/2032 01/01/2013 MOHD HUSSAIN SSLC Rs.250 /AA-8481/ GOMA KARGIL LADAKH JAMMU AND KASHMIR 194103 A+ M MCWG LMV GOMA KARGIL LADAKH JAMMU AND KASHMIR 194103 A MOLE ON RT. ARM. S/W BY NATIONAL INFORMATICS CENTRE ARTO, KARGIL(JK-07) Driving License issue Register For Period 11/12/2012 TO 30/09/2015 2 Sl No. -

Indian Railways from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia This Article Is About the Organisation

Indian Railways From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia This article is about the organisation. For general information on railways in India, see Rail transport in India. [hide]This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. This article may contain an excessive amount of intricate detail that may only interest a specific audience. (August 2015) This article may be written from a fan's point of view, rather than a neutral point of view. (August 2015) This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2015) Indian Railways "Lifeline to the Nation" Type Public sector undertaking Industry Railways Founded 16 April 1853 (162 years ago)[1] Headquarters New Delhi, India Area served India (also limited service to Nepal,Bangladesh and Pakistan) Key people Suresh Prabhakar Prabhu (Minister of Railways, 2014–) Services Passenger railways Freight services Parcel carrier Catering and Tourism Services Parking lot operations Other related services ₹1634.5 billion (US$25 billion) (2014–15)[2] Revenue ₹157.8 billion (US$2.4 billion) (2013–14)[2] Profit Owner Government of India (100%) Number of employees 1.334 million (2014)[3] Parent Ministry of Railways throughRailway Board (India) Divisions 17 Railway Zones Website www.indianrailways.gov.in Indian Railways Reporting mark IR Locale India Dates of operation 16 April 1853–Present Track gauge 1,676 mm (5 ft 6 in) 3 1,000 mm (3 ft 3 ⁄8 in) 762 mm (2 ft 6 in) 610 mm (2 ft) Headquarters New Delhi, India Website www.indianrailways.gov.in Indian Railways (reporting mark IR) is an Indian state-owned enterprise, owned and operated by the Government of India through the Ministry of Railways.