Introduction PROJECT BACKGROUND

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Watery Entanglements in the Cypriot Hinterland

1 Article 2 Watery Entanglements in the Cypriot Hinterland 3 Louise Steel 1 4 1 Faculty of Humanities and Performing Arts, University of Wales Trinity Saint David, Lampeter, Ceredigion 5 SA48 7ED; [email protected] 6 7 Abstract: This paper examines how water shaped people’s interaction with the landscape in Cyprus 8 during the Bronze Age. The theoretical approach is drawn from the new materialisms, effectively a 9 ‘turn to matter’, which emphasises the very materiality of the world and challenges the privileged 10 position of human agents over the rest of the environment. The paper specifically moves away from 11 more traditional approaches to landscape archaeology, such as central place theory and more 12 recently network theory, which serve to separate and distance people from the physical world they 13 live in, and indeed are a part of; instead it focuses on an approach that embeds humans, and the 14 social/material worlds they create, as part of the environment, exploring human interactions within 15 the landscape as assemblages, or entanglements of matter. It specifically emphasises the materiality 16 and agency of water and how this shaped people’s engagement with, and movement through, their 17 landscape. The aim is to encourage archaeologists to engage with the materiality of things, to better 18 understand how people and other matter co-create the material (including social) world. 19 Keywords: Cyprus; Bronze Age; water; materiality; new materialisms; entanglements; assemblages; 20 networks; central place theory 21 22 1. Introduction: A New Materialist Approach to Past Environments 23 This paper seeks to evaluate how the agency of water shaped the development of the Cypriot 24 landscape during the Bronze Age, focusing on how the natural world itself shaped peoples’ 25 engagement with their environment. -

200 Land Opportunities Below €50.000 with Significant Discounts from Market Value About Us

200 Land Opportunities below €50.000 with significant discounts from Market Value About us Delfi Properties holds a wide range of properties available for sale and for rent across Greece and Cyprus in most asset classes. Our dedicated transaction professionals are available to provide additional information on all of the properties being marketed and ready to support you throughout the process from your first inquiry through to sale completion. Nicosia Office Paphos OfficePaphos Office 1st & 2nd Floor Office 9, Office 9, 20 Katsoni Str. & AchepansAchepans 2 , 2 , Kyriakou Matsi Ave., AnavargosAn 8026avargos Paphos, 8026 Paphos, 1082 Nicosia, Cyprus Cyprus Cyprus +357 22 000093 +357 26 010574+357 26 010574 www.delfiproperties.com.cy www.delfiproperties.com.cywww.delfiproperties.com.cy [email protected] [email protected]@delfipropertie Information contained in our published works have been obtained from sources believed to be reliable at the time of publication. However, we do not guarantee the accuracy or completeness of any information published herein and shall not be held responsible for any changes, errors, omissions, or claims for damages arising out of use, inability to use, or with regard to the accuracy or sufficiency of the information contained in this publication. 2 Contents Paphos p. 44 Limassol p. 28 Larnaca p. 69 Famagusta p. 75 Nicosia p. 04 3 Nicosia is a true European capital, where the old town and modern city, the traditional and contemporary fuse together to give residents a unique experience unlike any other in Cyprus. With a number of landmarks, museums, theatres, musical events and galleries, life in Nicosia is exciting, while its convenient location between sea and mountains enables you to explore Cyprus and enjoy everything it has to offer within just a short drive. -

Mfi Id Name Address Postal City Head Office

MFI ID NAME ADDRESS POSTAL CITY HEAD OFFICE CYPRUS Central Banks CY000001 Central Bank of Cyprus 80, Tzon Kennenty Avenue 1076 Nicosia Total number of Central Banks : 1 Credit Institutions CY130001 Allied Bank SAL 276, Archiepiskopou Makariou III Avenue 3105 Limassol LB Allied Bank SAL CY110001 Alpha Bank Limited 1, Prodromou Street 1095 Nicosia CY130002 Arab Bank plc 1, Santaroza Avenue 1075 Nicosia JO Arab Bank plc CY120001 Arab Bank plc 1, Santaroza Avenue 1075 Nicosia JO Arab Bank plc CY130003 Arab Jordan Investment Bank SA 23, Olympion Street 3035 Limassol JO Arab Jordan Investment Bank SA CY130006 Bank of Beirut and the Arab Countries SAL 135, Archiepiskopou Makariou III Avenue 3021 Limassol LB Bank of Beirut and the Arab Countries SAL CY130032 Bank of Beirut SAL 6, Griva Digeni Street 3106 Limassol LB Bank of Beirut SAL CY110002 Bank of Cyprus Ltd 51, Stasinou Street, Strovolos 2002 Nicosia CY130007 Banque Européenne pour le Moyen - Orient SAL 227, Archiepiskopou Makariou III Avenue 3105 Limassol LB Banque Européenne pour le Moyen - Orient SAL CY130009 Banque SBA 8C, Tzon Kennenty Street 3106 Limassol FR Banque SBA CY130010 Barclays Bank plc 88, Digeni Akrita Avenue 1061 Nicosia GB Barclays Bank plc CY130011 BLOM Bank SAL 26, Vyronos Street 3105 Limassol LB BLOM Bank SAL CY130033 BNP Paribas Cyprus Ltd 319, 28 Oktovriou Street 3105 Limassol CY130012 Byblos Bank SAL 1, Archiepiskopou Kyprianou Street 3036 Limassol LB Byblos Bank SAL CY151414 Co-operative Building Society of Civil Servants Ltd 34, Dimostheni Severi Street 1080 Nicosia -

Lem Esos Bay Larnaka Bay Vfr Routes And

AIP CYPRUS LARNAKA APP : 121.2 MHz AD2 LCLK 24 VFR VFR ROUTES - ICAO LARNAKA TWR : 119.4 MHz AERONAUTICAL INFORMATION 09/05/2009 10' 20' 30' 40' 50' 33° E 33° E 33° E 33° E 33° E Nicosia Airport (645) (740) remains closed Tower REPUBLIC OF CYPRUS Mammari until further notice Crane 10' 10' (480) 35° N 35° N (465) LEFKOSIA VFR ROUTES AND TRAINING AREAS 02 BUFFER (760) (825) (850) CYTA Stadium CBC Tower ZONE (905) Tower BUFFER SCALE : 1:250000 Astromeritis Pylons (595) Tower (600) (570) ZONE AREA UNDER TURKISH OCCUPATION Positions are referred to World Geodetic System 1984 Datum . (625) Elevations and Altitudes are in feet above Mean Sea Level. Akaki Palaiometocho Bearings and Tracks are magnetic. (745) Distances are in Nautical miles. Peristerona (1065) GSP Stadium Magnetic Variation : 04°00’E (2008) Mast LC(R) Pylons Projection : UTM Zone 36 Northern Hemisphere. Potami (595) Geri Sources : The aeronautical data have been designed by the KLIROU Lakatamia VAR 4° E (925)Lakatameia Department of Civil Aviation. The chart has been compiled by the Agios Orounta 46 122.5 MHz LC(D)-18 3000ft Department of Lands and Surveys using sources available in the Nikolaos Kato Deftera max 5000 ft 3500ft 1130 SFC Geographic Database. 1235 SFC LC(D)-37 1030 Vyzakia 1145 Tseri 7 19 10000ft 54 Agios 34 2 LC(D)-15 LC(D)-20 SFC Ioannis 1340 FL105 (1790) Vyzakia 1760 SFC Kato Moni Agios Psimolofou Mast LC(D)-06 dam Panteleimon Ergates SBA Boundary LEGEND 2110 3000ft 2025 (1140) Idalion SFC Achna Arediou MARKI Potamia AERONAUTICAL HYDROLOGICAL Klirou PERA dam FEATURES FEATURES dam 106° 122.5 MHz Mitsero N 35°01'57" 3000ft BUFFER 2225 MOSPHILOTI Kingsfield VFR route Aeronautical Water LC(D)-19 E 033°15'15" ZONE Xyliatos 7.6 NM 1195 N 34°57'12" reporting 6000ft Klirou Agios Xylotymvou ground reservoir 1605 Irakleidios 1465 points 3120 SFC KLIROU E 033°25'12" Pyla lights Tamassos Xyliatos Ag. -

Watery Entanglements in the Cypriot Hinterland

land Article Watery Entanglements in the Cypriot Hinterland Louise Steel ID Faculty of Humanities and Performing Arts, University of Wales Trinity Saint David, Lampeter SA48 7ED, Ceredigion, Wales, UK; [email protected] Received: 21 August 2018; Accepted: 3 September 2018; Published: 5 September 2018 Abstract: This paper examines how water shaped people’s interaction with the landscape in Cyprus during the Bronze Age. The theoretical approach is drawn from the new materialisms, effectively a ‘turn to matter’, which emphasises the very materiality of the world and challenges the privileged position of human agents over the rest of the environment. The paper specifically moves away from more traditional approaches to landscape archaeology, such as central place theory and more recently network theory, which serve to separate and distance people from the physical world they live in, and indeed are a part of; instead, it focuses on an approach that embeds humans, and the social/material worlds they create, as part of the environment, exploring human interactions within the landscape as assemblages, or entanglements of matter. It specifically emphasises the materiality and agency of water and how this shaped people’s engagement with, and movement through, their landscape. The aim is to encourage archaeologists to engage with the materiality of things, to better understand how people and other matter co-create the material (including social) world. Keywords: Cyprus; Bronze Age; water; materiality; new materialisms; entanglements; assemblages; networks; central place theory 1. Introduction: A New Materialist Approach to Past Environments This paper seeks to evaluate how the agency of water shaped the development of the Cypriot landscape during the Bronze Age, focusing on how the natural world itself shaped peoples’ engagement with their environment. -

Frankish-Venetian Cyprus: JSACE 3/16

97 Journal of Sustainable Architecture and Civil Engineering 2016/3/16 Frankish-Venetian Cyprus: JSACE 3/16 Effects of the Renaissance Frankish-Venetian Cyprus: Effects of the Renaissance on on the Ecclesiastical the Ecclesiastical Architecture of the Architecture of the Island Island Received 2016/09/22 Nasso Chrysochou Accepted after Assistant professor, Department of Architecture, Frederick University revision Demetriou Hamatsou 13, 1040 Nicosia 2016/10/24 Corresponding author: [email protected] http://dx.doi.org/10.5755/j01.sace.16.3.16278 The paper deals with the effects of the Renaissance on the Orthodox ecclesiastical architecture of the island. Even though the Latin monuments of the island have been thoroughly researched, there are only sporadic works that deal with the Orthodox ecclesiastical architecture of the period. The doctoral thesis of the author in waiting to be published is the only complete work on the subject. The methodology used, involved bibliographic research and to a large degree field research to establish the measurements of all the monuments. Cyprus during the late 15th to late 16th century was under Venetian rule but the government was more interested in establishing a defensive strategy against the threat of the Ottoman Empire rather than building the fine renaissance architecture that was realized in Italy. However, small morphological details and typologies managed to infiltrate the local architecture. This was done through the import of ideas and designs by Venetian architects and engineers who travelled around the colonies or through the use of easily transferable drawings and manuals of architects such as Serlio and Palladio. -

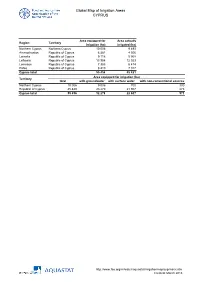

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CYPRUS

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CYPRUS Area equipped for Area actually Region Territory irrigation (ha) irrigated (ha) Northern Cyprus Northern Cyprus 10 006 9 493 Ammochostos Republic of Cyprus 6 581 4 506 Larnaka Republic of Cyprus 9 118 5 908 Lefkosia Republic of Cyprus 13 958 12 023 Lemesos Republic of Cyprus 7 383 6 474 Pafos Republic of Cyprus 8 410 7 017 Cyprus total 55 456 45 421 Area equipped for irrigation (ha) Territory total with groundwater with surface water with non-conventional sources Northern Cyprus 10 006 9 006 700 300 Republic of Cyprus 45 449 23 270 21 907 273 Cyprus total 55 456 32 276 22 607 573 http://www.fao.org/nr/water/aquastat/irrigationmap/cyp/index.stm Created: March 2013 Global Map of Irrigation Areas CYPRUS Area equipped for District / Municipality Region Territory irrigation (ha) Bogaz Girne Main Region Northern Cyprus 82.4 Camlibel Girne Main Region Northern Cyprus 302.3 Girne East Girne Main Region Northern Cyprus 161.1 Girne West Region Girne Main Region Northern Cyprus 457.9 Degirmenlik Lefkosa Main Region Northern Cyprus 133.9 Ercan Lefkosa Main Region Northern Cyprus 98.9 Guzelyurt Lefkosa Main Region Northern Cyprus 6 119.4 Lefke Lefkosa Main Region Northern Cyprus 600.9 Lefkosa Lefkosa Main Region Northern Cyprus 30.1 Akdogan Magosa Main Region Northern Cyprus 307.7 Gecitkale Magosa Main Region Northern Cyprus 71.5 Gonendere Magosa Main Region Northern Cyprus 45.4 Magosa A Magosa Main Region Northern Cyprus 436.0 Magosa B Magosa Main Region Northern Cyprus 52.9 Mehmetcik Magosa Main Region Northern -

Name Address Postal City Mfi Id Head Office Res* Cyprus

MFI ID NAME ADDRESS POSTAL CITY HEAD OFFICE RES* CYPRUS Central Banks CY000001 Central Bank of Cyprus 80, Tzon Kennenty Avenue 1076 Nicosia No Total number of Central Banks : 1 Credit Institutions CY110001 Alpha Bank Limited 1, Prodromou Street 1095 Nicosia No CY120001 Arab Bank plc 1, Santaroza Avenue 1075 Nicosia JO Arab Bank plc No CY120004 Arab Jordan Investment Bank SA 23, Olympion Street 3035 Limassol JO Arab Jordan Investment No Bank SA CY120021 Bank of Beirut SAL 6, Griva Digeni Street 3106 Limassol LB Bank of Beirut SAL No CY110002 Bank of Cyprus Public Company Ltd 51, Stasinou Street, Strovolos 2002 Nicosia No CY120026 Bankmed sal 3722 Limassol LB Bankmed sal No CY120006 Banque Européenne pour le Moyen - Orient 227, Archiepiskopou Makariou III 3105 Limassol LB Banque Européenne pour No SAL Avenue le Moyen - Orient SAL CY120007 Banque SBA 8C, Tzon Kennenty Street 3106 Limassol FR Banque SBA No CY120008 Barclays Bank plc 88, Digeni Akrita Avenue 1061 Nicosia GB Barclays Bank plc No CY120005 BBAC SAL 135, Archiepiskopou Makariou III 3021 Limassol LB BBAC SAL No Avenue CY120009 BLOM Bank SAL 26, Vyronos Street 3105 Limassol LB BLOM Bank SAL No CY110018 BNP Paribas Cyprus Ltd 319, 28 Oktovriou Street 3105 Limassol No CY120010 Byblos Bank SAL 1, Archiepiskopou Kyprianou Street 3036 Limassol LB Byblos Bank SAL No CY120023 Central Cooperative Bank PLC 1509 Nicosia BG Central Cooperative Bank No PLC CY151414 Co-operative Building Society of Civil 34, Dimostheni Severi Street 1080 Nicosia No Servants Ltd CY110003 Co-operative Central Bank -

S CHOOL BOARDS NICOSIA ΕΠΑΡΧΙΑ: School Board Name

SCHOOL BOARDS ΕΠΑΡΧΙΑ: NICOSIA School Board Name Address Postal Code District Tel Tel Fax Email EFOREIA ARMENIKON SCHOLEION KYPROU P.O.Box 16173 2086 Lefkosia NICOSIA 22422218 22311483 [email protected] SCHOLIKI EFOREIA AGIAS VARVARAS 53 Leof. Grigori Afxentiou 2560 Agia Varvara NICOSIA 22522270 22523711 [email protected] SCHOLIKI EFOREIA AGIAS MARINAS XYLIATOU 2772 Agia Marina Xyliatou NICOSIA 22852775 22852847 [email protected] SCHOLIKI EFOREIA AGIOU DOMETIOU 23 Kentavrou 2364 Agios Dometios NICOSIA 22777759 22776570 [email protected] SCHOLIKI EFOREIA AGIOU EPIFANIOU 2610 Agios Epifanios NICOSIA 22633901 22633902 [email protected] SCHOLIKI EFOREIA AGIOU IOANNI LEFKOSIAS Apostolou Andrea 1 2611 Agios Ioannis Lefkosias NICOSIA 22634311 22634310 [email protected] SCHOLIKI EFOREIA AGIOU MARONA 20 Agiou Marona 2304 Anthoupoli NICOSIA 22721510 22372205 [email protected] SCHOLIKI EFOREIA AGION TRIMITHIAS 40 Archiepiskopou Makariou III 2671 Agioi Trimithias NICOSIA 22832470 22835054 [email protected] SCHOLIKI EFOREIA AGLANTZIAS P.O.Box 20266 2150 Aglantzia NICOSIA 22333847 22337901 [email protected] SCHOLIKI EFOREIA AGROKIPIAS 2617 Agrokipia NICOSIA 22634111 22634111 [email protected] SCHOLIKI EFOREIA AKAKIOU Grigori Afxentiou 2720 Akaki NICOSIA 22823466 22824524 [email protected] SCHOLIKI EFOREIA ALAMPRAS 2563 Alampra NICOSIA 22522457 22526402 [email protected] SCHOLIKI EFOREIA -

Pagemaker Econ Stat 2003 300805

ȀȊȆȇǿǹȀǾ ǻǾȂȅȀȇǹȉǿǹ REPUBLIC OF CYPRUS ȈȉǹȉǿȈȉǿȀȅǿ ȀȍǻǿȀȅǿ ǻǾȂȍȃ, ȀȅǿȃȅȉǾȉȍȃ Ȁǹǿ Ǽȃȅȇǿȍȃ ȉǾȈ ȀȊȆȇȅȊ STATISTICAL CODES OF MUNICIPALITIES, COMMUNITIES AND QUARTERS OF CYPRUS 2010 ȈȉǹȉǿȈȉǿȀǾ ȊȆǾȇǼȈǿǹ STATISTICAL SERVICE ȈIJĮIJȚıIJȚțȠȓ ȀȦįȚțȠȓ: x ȈİȚȡȐ ǿ x ǹȡ. DzțșİıȘȢ 6 Statistical Codes: x ȈİȚȡȐ ǿ x Report No 6 - 3 - ȆȇȅȁȅīȅȈ PREFACE ǹȣIJȒ İȓȞĮȚ Ș ȑțIJȘ ȑțįȠıȘ IJȠȣ įȘµȠıȚİȪµĮIJȠȢ This is the sixth edition of the publication “Statistical «ȈIJĮIJȚıIJȚțȠȓ ȀȦįȚțȠȓ ǻȒµȦȞ, ȀȠȚȞȠIJȒIJȦȞ țĮȚ ǼȞȠȡȚȫȞ Codes of Municipalities, Communities and Quarters of IJȘȢ ȀȪʌȡȠȣ» țĮȚ ʌĮȡȠȣıȚȐȗİȚ IJȠ ĮȞĮșİȦȡȘµȑȞȠ Cyprus” and it presents the updated statistical coding ıIJĮIJȚıIJȚțȩ țȦįȚțȩ ıȪıIJȘµĮ IJȦȞ IJȠʌȚțȫȞ İįĮijȚțȫȞ system of the local territorial units (municipalities, µȠȞȐįȦȞ (įȒµȦȞ, țȠȚȞȠIJȒIJȦȞ țĮȚ İȞȠȡȚȫȞ) IJȘȢ ȀȪʌȡȠȣ. communities and quarters) of Cyprus. The revised ȉȠ ĮȞĮșİȦȡȘµȑȞȠ ıȪıIJȘµĮ ȖİȦȖȡĮijȚțȫȞ țȦįȚțȫȞ geographical coding system was prepared in ȑȖȚȞİ ıİ ıȣȞİȡȖĮıȓĮ µİ ȐȜȜİȢ ĮȡµȩįȚİȢ ȊʌȘȡİıȓİȢ țĮȚ collaboration with other competent Services and ȉµȒµĮIJĮ țĮȚ ıIJȠȤİȪİȚ ıIJȘȞ İȣȡȪIJİȡȘ įȣȞĮIJȒ ȤȡȒıȘ. Departments and aims at its broadest possible use. Ǿ ȖİȦȖȡĮijȚțȒ IJĮȟȚȞȩµȘıȘ ʌİȡȚȜĮµȕȐȞİȚ IJȚȢ įȚȠȚțȘIJȚțȑȢ The geographical classification pertains to the İʌĮȡȤȓİȢ, IJȠȣȢ įȒµȠȣȢ, IJȚȢ țȠȚȞȩIJȘIJİȢ țĮȚ IJȚȢ İȞȠȡȓİȢ. administrative districts, the municipalities, the ȉĮ ȠȞȩµĮIJĮ IJȦȞ įȒµȦȞ/țȠȚȞȠIJȒIJȦȞ țĮȚ İȞȠȡȚȫȞ İȓȞĮȚ IJĮ communities and the quarters. The names of İʌȓıȘµĮ ȠȞȩµĮIJĮ µİ IJȘ ȖȡĮijȒ ȩʌȦȢ țĮșȠȡȓıIJȘțİ Įʌȩ municipalities/communities and quarters are the official IJȘ ȂȩȞȚµȘ ȀȣʌȡȚĮțȒ ǼʌȚIJȡȠʌȒ ȉȣʌȠʌȠȓȘıȘȢ names which have been determined by the Cyprus īİȦȖȡĮijȚțȫȞ ȅȞȠµȐIJȦȞ ıIJȘȞ ǼȜȜȘȞȚțȒ ȖȜȫııĮ țĮȚ IJȘ Permanent Committee for the Standardization of µİIJĮȖȡĮijȒ IJȠȣȢ ıIJȠ ȇȦµĮȞȚțȩ ĮȜijȐȕȘIJȠ. Geographical Names in the Greek language and transliterated in Roman characters. ĬĮ ʌȡȑʌİȚ ȞĮ ıȘµİȚȦșİȓ ȩIJȚ IJȠ țȦįȚțȩ ıȪıIJȘµĮ It should be noted that the coding system covers the țĮȜȪʌIJİȚ ȠȜȩțȜȘȡȘ IJȘȞ ȀȪʌȡȠ, įȘȜ. -

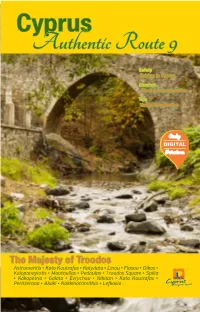

Cyprus Authentic Route 9

Cyprus Authentic Route 9 Safety Driving in Cyprus Comfort Rural Accommodation Tips Useful Information Only DIGITAL Version The Majesty of Troodos Astromeritis • Kato Koutrafas • Katydata • Linou • Flasou • Oikos • Kalopanayiotis • Moutoullas • Pedoulas • Troodos Square • Spilia • Kakopetria • Galata • Evrychou • Nikitari • Kato Koutrafas • Peristerona • Akaki • Kokkinotrimithia • Lefkosia Route 9 Lefkosia – Kokkinotrimithia – Akaki – Peristerona – Astromeritis – Kato Koutrafas – Katydata – Linou – Flasou – Oikos – Kalopanayiotis – Moutoullas – Pedoulas – Troodos Square – Spilia – Kakopetria – Galata – Evrychou – Nikitari – Kato Koutrafas – Peristerona – Akaki – Kokkinotrimithia – Lefkosia Sysklipos Agirda Profitis scale 1:400,000 Pileri Karpaseia Kampyli Ilias Agia Pano 0 1 2 4 6 8 Kilometers Kiomourtzou Dikomo Eirini Agios Krini Asomatos Ermolaos Kontemenos Kalo Chorio Fota Kato Dyo Kapouti Dikomo Potamoi Skylloura Syrianochori Agia Agios Kanli Kioneli Marina Kyra Vasileios Morfou Ortakioi Masari Gerolakkos Argaki Fyllia MORFOU BAY Prastio Kato Agios Katokopia Deneia Zodeia Mammari Dometios Nikitas Pano Avlona Kazivera Zodeia Kokkinotrimithia Egkomi Pentageia Astromeritis Nicosia International Karavostasi Airport (Not in use) Elia Akaki Strovolos Kalo Peristerona Agioi Peristeronari Angolemi Palaiometocho Lakatameia Chorio Trimithias Lefka Petra Potami Orounta Agios Nikolaos Agios Pano Meniko Anthoupoli Kato Panagia Chrysospiliotissa Skouriotissa Georgios Koutrafas Pano Koutrafas Kato Deftera Katydata Agios Deftera Nikitari Vyzakia Kato -

A Visitor´S Map of Cyprus

20° 10° 0° 10° 20° 30°40° 50° Kleides Islands LOCATION DIAGRAM Cape Apostolos Andreas 55°55° 50°50° N Kordylia Islet A E C O ApostolosApostolosApostolos ApostolosApostolosApostolos AndreasAndreasAndreas C 50°50° AndreasAndreasAndreas I A Visitor΄s Map of Cyprus %%PanagiaPanagiaPanagia Afentrika AfentrikaAfentrika 45°45° EE PanagiaPanagiaPanagia Afentrika AfentrikaAfentrika T N P A E L U R O R %% T AgiosAgiosAgios A 45°45° FilonFilonFilon 40°40° FilonFilonFilon 40°40° S c a l e 1 : 3 5 0 . 0 0 0 Rizokarpaso PanagiaPanagiaPanagia 35°35° EleousaEleousaEleousa A EleousaEleousaEleousa M E D I T A SS I A E R I A R Kilometres 10 0102030 Kilometres %% I A A 35°35° 5 S F N AgiosAgiosAgios Thyrsos ThyrsosThyrsos A F R I E (Rock-Cut)(Rock-Cut)(Rock-Cut) A 30°30° A I CK A P A N R S E A KYPROS A K (CYPRUS) 30°30° Aigialousa 500 10001000 Kms Kms Kms 00 500 000 000000 Galinoporni 222000 Agios Melanarga Andronikos 5° 0° 5°10° 15° 20° 25° 30° 35° Koroveia Kila Islet Koilanemos PanagiaPanagiaPanagia KanakariaKanakariaKanakaria KanakariaKanakariaKanakaria Agios Symeon %% Platanissos %% Vothylakas Lythragkomi Vasili Neta Leonarisso Eptakomi Koma Davlos Galateia tou Gialou KantaraKantaraKantara Komi Cape Kormakitis Livadia Tavrou Forest Flamoudi Station K Krideia Agios a s Efstathios Vokolida 666000000 tro Livera AKANTHOU 666000 s 000000 Ovgoros 444000 444 000000 Agios Theodoros LampousaLampousaLampousa 222000 Patriki AcheiropoiitosAcheiropoiitosAcheiropoiitos LampousaLampousaLampousa Gerani AcheiropoiitosAcheiropoiitosAcheiropoiitos%% Glykiotissa Islet