A Case Study of Boreal Black Spruce Forest Bryophytes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coptis Trifolia Conservation Assessment

CONSERVATION ASSESSMENT for Coptis trifolia (L.) Salisb. Originally issued as Management Recommendations December 1998 Marty Stein Reconfigured-January 2005 Tracy L. Fuentes USDA Forest Service Region 6 and USDI Bureau of Land Management, Oregon and Washington CONSERVATION ASSESSMENT FOR COPTIS TRIFOLIA Table of Contents Page List of Tables ................................................................................................................................. 2 List of Figures ................................................................................................................................ 2 Summary........................................................................................................................................ 4 I. NATURAL HISTORY............................................................................................................. 6 A. Taxonomy and Nomenclature.......................................................................................... 6 B. Species Description ........................................................................................................... 6 1. Morphology ................................................................................................................... 6 2. Reproductive Biology.................................................................................................... 7 3. Ecological Roles ............................................................................................................. 7 C. Range and Sites -

Economic and Ethnic Uses of Bryophytes

Economic and Ethnic Uses of Bryophytes Janice M. Glime Introduction Several attempts have been made to persuade geologists to use bryophytes for mineral prospecting. A general lack of commercial value, small size, and R. R. Brooks (1972) recommended bryophytes as guides inconspicuous place in the ecosystem have made the to mineralization, and D. C. Smith (1976) subsequently bryophytes appear to be of no use to most people. found good correlation between metal distribution in However, Stone Age people living in what is now mosses and that of stream sediments. Smith felt that Germany once collected the moss Neckera crispa bryophytes could solve three difficulties that are often (G. Grosse-Brauckmann 1979). Other scattered bits of associated with stream sediment sampling: shortage of evidence suggest a variety of uses by various cultures sediments, shortage of water for wet sieving, and shortage around the world (J. M. Glime and D. Saxena 1991). of time for adequate sampling of areas with difficult Now, contemporary plant scientists are considering access. By using bryophytes as mineral concentrators, bryophytes as sources of genes for modifying crop plants samples from numerous small streams in an area could to withstand the physiological stresses of the modern be pooled to provide sufficient material for analysis. world. This is ironic since numerous secondary compounds Subsequently, H. T. Shacklette (1984) suggested using make bryophytes unpalatable to most discriminating tastes, bryophytes for aquatic prospecting. With the exception and their nutritional value is questionable. of copper mosses (K. G. Limpricht [1885–]1890–1903, vol. 3), there is little evidence of there being good species to serve as indicators for specific minerals. -

Vermont Natural Community Types

Synonymy of Vermont Natural Community Types with National Vegetation Classification Associations Eric Sorenson and Bob Zaino Natural Heritage Inventory Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department October 17, 2019 Vermont Natural Community Type Patch State National and International Vegetation Classification. NatureServe. 2019. Size Rank NatureServe Explorer: An online encyclopedia of life. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Spruce-Fir-Northern Hardwood Forest Formation Subalpine Krummholz S S1 Picea mariana - Abies balsamea / Sibbaldiopsis tridentata Shrubland (CEGL006038); (Picea mariana, Abies balsamea) / Kalmia angustifolia - Ledum groenlandicum Dwarf-shrubland Montane Spruce-Fir Forest L-M S3 Picea rubens - Abies balsamea - Sorbus americana Forest (CEGL006128) Variant: Montane Fir Forest L-M S3 Abies balsamea - (Betula papyrifera var. cordifolia) Forest (CEGL006112) Variant: Montane Spruce Forest Lowland Spruce-Fir Forest L-M S3 Picea mariana - Picea rubens / Pleurozium schreberi Forest (CEGL006361) Variant: Well-Drained Lowland Spruce- L S2 Picea rubens - Abies balsamea - Betula papyrifera Forest (CEGL006273); Fir Forest Picea mariana - Picea rubens / Rhododendron canadense / Cladina spp. Woodland (CEGL006421) Montane Yellow Birch-Red Spruce Forest M S3 Betula alleghaniensis - Picea rubens / Dryopteris campyloptera Forest (CEGL006267) Variant: Montane Yellow Birch-Sugar L S3 Maple-Red Spruce Forest Red Spruce-Northern Hardwood Forest M S5 Betula alleghaniensis - Picea rubens / Dryopteris campyloptera Forest (CEGL006267) Red Spruce-Heath -

Appendix 2: Plant Lists

Appendix 2: Plant Lists Master List and Section Lists Mahlon Dickerson Reservation Botanical Survey and Stewardship Assessment Wild Ridge Plants, LLC 2015 2015 MASTER PLANT LIST MAHLON DICKERSON RESERVATION SCIENTIFIC NAME NATIVENESS S-RANK CC PLANT HABIT # OF SECTIONS Acalypha rhomboidea Native 1 Forb 9 Acer palmatum Invasive 0 Tree 1 Acer pensylvanicum Native 7 Tree 2 Acer platanoides Invasive 0 Tree 4 Acer rubrum Native 3 Tree 27 Acer saccharum Native 5 Tree 24 Achillea millefolium Native 0 Forb 18 Acorus calamus Alien 0 Forb 1 Actaea pachypoda Native 5 Forb 10 Adiantum pedatum Native 7 Fern 7 Ageratina altissima v. altissima Native 3 Forb 23 Agrimonia gryposepala Native 4 Forb 4 Agrostis canina Alien 0 Graminoid 2 Agrostis gigantea Alien 0 Graminoid 8 Agrostis hyemalis Native 2 Graminoid 3 Agrostis perennans Native 5 Graminoid 18 Agrostis stolonifera Invasive 0 Graminoid 3 Ailanthus altissima Invasive 0 Tree 8 Ajuga reptans Invasive 0 Forb 3 Alisma subcordatum Native 3 Forb 3 Alliaria petiolata Invasive 0 Forb 17 Allium tricoccum Native 8 Forb 3 Allium vineale Alien 0 Forb 2 Alnus incana ssp rugosa Native 6 Shrub 5 Alnus serrulata Native 4 Shrub 3 Ambrosia artemisiifolia Native 0 Forb 14 Amelanchier arborea Native 7 Tree 26 Amphicarpaea bracteata Native 4 Vine, herbaceous 18 2015 MASTER PLANT LIST MAHLON DICKERSON RESERVATION SCIENTIFIC NAME NATIVENESS S-RANK CC PLANT HABIT # OF SECTIONS Anagallis arvensis Alien 0 Forb 4 Anaphalis margaritacea Native 2 Forb 3 Andropogon gerardii Native 4 Graminoid 1 Andropogon virginicus Native 2 Graminoid 1 Anemone americana Native 9 Forb 6 Anemone quinquefolia Native 7 Forb 13 Anemone virginiana Native 4 Forb 5 Antennaria neglecta Native 2 Forb 2 Antennaria neodioica ssp. -

Summary Data

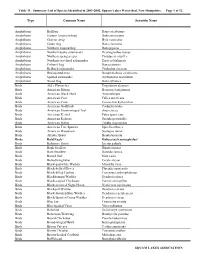

Table 11. Summary List of Species Identified in 2001-2002, Squam Lakes Watershed, New Hampshire. Page 1 of 12 Type Common Name Scientific Name Amphibians Bullfrog Rana catesbeiana Amphibians Eastern American toad Bufo americanus Amphibians Gray treefrog Hyla versicolor Amphibians Green frog Rana clamitans Amphibians Northern leopard frog Rana pipiens Amphibians Northern dusky salamander Desmognathus fuscus Amphibians Northern spring peeper Pseudacris crucifer Amphibians Northern two-lined salamander Eurycea bislineata Amphibians Pickerel frog Rana palustris Amphibians Redback salamander Plethodon cinereus Amphibians Red-spotted newt Notophthalmus viridescens Amphibians Spotted salamander Ambystoma maculatum Amphibians Wood frog Rana sylvatica Birds Alder Flycatcher Empidonax alnorum Birds American Bittern Botaurus lentiginosus Birds American Black Duck Anas rubripes Birds American Coot Fulica americana Birds American Crow Corvus brachyrhynchos Birds American Goldfinch Carduelis tristis Birds American Green-winged Teal Anas crecca Birds American Kestrel Falco sparverius Birds American Redstart Setophaga ruticilla Birds American Robin Turdus migratorius Birds American Tree Sparrow Spizella arborea Birds American Woodcock Scolopax minor Birds Atlantic Brant Branta bernicla Birds Bald Eagle* Haliaeetus leucocephalus* Birds Baltimore Oriole Icterus galbula Birds Bank Swallow Riparia riparia Birds Barn Swallow Hirundo rustica Birds Barred Owl Strix varia Birds Belted Kingfisher Ceryle alcyon Birds Black-and-white Warbler Mniotilta varia Birds -

Species List For: Labarque Creek CA 750 Species Jefferson County Date Participants Location 4/19/2006 Nels Holmberg Plant Survey

Species List for: LaBarque Creek CA 750 Species Jefferson County Date Participants Location 4/19/2006 Nels Holmberg Plant Survey 5/15/2006 Nels Holmberg Plant Survey 5/16/2006 Nels Holmberg, George Yatskievych, and Rex Plant Survey Hill 5/22/2006 Nels Holmberg and WGNSS Botany Group Plant Survey 5/6/2006 Nels Holmberg Plant Survey Multiple Visits Nels Holmberg, John Atwood and Others LaBarque Creek Watershed - Bryophytes Bryophte List compiled by Nels Holmberg Multiple Visits Nels Holmberg and Many WGNSS and MONPS LaBarque Creek Watershed - Vascular Plants visits from 2005 to 2016 Vascular Plant List compiled by Nels Holmberg Species Name (Synonym) Common Name Family COFC COFW Acalypha monococca (A. gracilescens var. monococca) one-seeded mercury Euphorbiaceae 3 5 Acalypha rhomboidea rhombic copperleaf Euphorbiaceae 1 3 Acalypha virginica Virginia copperleaf Euphorbiaceae 2 3 Acer negundo var. undetermined box elder Sapindaceae 1 0 Acer rubrum var. undetermined red maple Sapindaceae 5 0 Acer saccharinum silver maple Sapindaceae 2 -3 Acer saccharum var. undetermined sugar maple Sapindaceae 5 3 Achillea millefolium yarrow Asteraceae/Anthemideae 1 3 Actaea pachypoda white baneberry Ranunculaceae 8 5 Adiantum pedatum var. pedatum northern maidenhair fern Pteridaceae Fern/Ally 6 1 Agalinis gattingeri (Gerardia) rough-stemmed gerardia Orobanchaceae 7 5 Agalinis tenuifolia (Gerardia, A. tenuifolia var. common gerardia Orobanchaceae 4 -3 macrophylla) Ageratina altissima var. altissima (Eupatorium rugosum) white snakeroot Asteraceae/Eupatorieae 2 3 Agrimonia parviflora swamp agrimony Rosaceae 5 -1 Agrimonia pubescens downy agrimony Rosaceae 4 5 Agrimonia rostellata woodland agrimony Rosaceae 4 3 Agrostis elliottiana awned bent grass Poaceae/Aveneae 3 5 * Agrostis gigantea redtop Poaceae/Aveneae 0 -3 Agrostis perennans upland bent Poaceae/Aveneae 3 1 Allium canadense var. -

Ecosites and Communities of Forested Rangelands

Saskatchewan Rangeland Ecosystems Ecosites and Communities of Forested Rangelands Jeff Thorpe and Bob Godwin Saskatchewan Research Council 2008 Funding for this publication provided by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada's Greencover Canada Program Ecosites and Communities of Forested Rangelands ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project was coordinated by the Saskatchewan Forest Centre (SFC), with major funding support from Agriculture and Agri-food Canada’s Greencover Canada Program. Additional funding supporting was received from: • Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture (SA) • Forest Service Branch, Saskatchewan Ministry of Environment (SE) • Parks Service Branch, Saskatchewan Ministry of Tourism, Parks, Culture, and Sport (STPCS) • Saskatchewan Research Council (SRC) Todd Jorgenson (SA) and Al Foster (SA) helped with planning and coordination of the project, and Larry White (SFC) dealt with financial administration. Michael McLaughlan (SE), Rob Wright (SE) and Bill Houston (PFRA) provided access to vegetation plot data. SA staff, including Todd Jorgenson, Al Foster, and numerous summer students, and PFRA staff (Jenny Calow and Michelle Graham) contributed significant time to field data collection. A major part of the fieldwork was done by SRC subcontractors Wade Sumners, Chet Neufeld, and Randy Reddekopp. John Hudson (independent botanist) helped to identify plant collections. Charlene Hudym (SRC) prepared the report. Finally, we would like to acknowledge the advice and example provided by Gerry Ehlert and Barry Adams of Alberta Sustainable Resource -

<I>Sphagnum</I> Peat Mosses

ORIGINAL ARTICLE doi:10.1111/evo.12547 Evolution of niche preference in Sphagnum peat mosses Matthew G. Johnson,1,2,3 Gustaf Granath,4,5,6 Teemu Tahvanainen, 7 Remy Pouliot,8 Hans K. Stenøien,9 Line Rochefort,8 Hakan˚ Rydin,4 and A. Jonathan Shaw1 1Department of Biology, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina 27708 2Current Address: Chicago Botanic Garden, 1000 Lake Cook Road Glencoe, Illinois 60022 3E-mail: [email protected] 4Department of Plant Ecology and Evolution, Evolutionary Biology Centre, Uppsala University, Norbyvagen¨ 18D, SE-752 36, Uppsala, Sweden 5School of Geography and Earth Sciences, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada 6Department of Aquatic Sciences and Assessment, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, SE-750 07, Uppsala, Sweden 7Department of Biology, University of Eastern Finland, P.O. Box 111, 80101, Joensuu, Finland 8Department of Plant Sciences and Northern Research Center (CEN), Laval University Quebec, Canada 9Department of Natural History, Norwegian University of Science and Technology University Museum, Trondheim, Norway Received March 26, 2014 Accepted September 23, 2014 Peat mosses (Sphagnum)areecosystemengineers—speciesinborealpeatlandssimultaneouslycreateandinhabitnarrowhabitat preferences along two microhabitat gradients: an ionic gradient and a hydrological hummock–hollow gradient. In this article, we demonstrate the connections between microhabitat preference and phylogeny in Sphagnum.Usingadatasetof39speciesof Sphagnum,withan18-locusDNAalignmentandanecologicaldatasetencompassingthreelargepublishedstudies,wetested -

Direct and Indirect Drivers of Moss Community Structure, Function, and Associated Microfauna Across a Successional Gradient

Ecosystems (2015) 18: 154–169 DOI: 10.1007/s10021-014-9819-8 Ó 2014 Springer Science+Business Media New York Direct and Indirect Drivers of Moss Community Structure, Function, and Associated Microfauna Across a Successional Gradient Micael Jonsson,1* Paul Kardol,2 Michael J. Gundale,2 Sheel Bansal,2,3 Marie-Charlotte Nilsson,2 Daniel B. Metcalfe,2,4 and David A. Wardle2 1Department of Ecology and Environmental Science, Umea˚ University, 90187 Umea˚ , Sweden; 2Department of Forest Ecology and Management, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, 90183 Umea˚ , Sweden; 3USDA Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station, Olympia Forestry Sciences Laboratory, 3625 93rd Avenue SW, Olympia, Washington 98512, USA; 4Department of Physical Geography and Ecosystem Science, Lund University, 22362 Lund, Sweden ABSTRACT Relative to vascular plants, little is known about munity. Our results show that different aspects of what factors control bryophyte communities or the moss community (that is, composition, func- how they respond to successional and environ- tional traits, moss-driven processes, and associated mental changes. Bryophytes are abundant in boreal invertebrate fauna) respond to different sets of forests, thus changes in moss community compo- environmental variables, and that these are not sition and functional traits (for example, moisture always the same variables as those that influence and nutrient content; rates of photosynthesis and the vascular plant community. Measures of moss respiration) may have important consequences for -

Additive Partitioning of Testate Amoeba Species Diversity Across Habitat

1 Published in European Journal of Protistology 51, 42-52, 2015 which should be used for any reference to this work Additive partitioning of testate amoeba species diversity across habitat hierarchy within the pristine southern taiga landscape (Pechora-Ilych Biosphere Reserve, Russia) a,∗ a b,c Andrey N. Tsyganov , Alexander A. Komarov , Edward A.D. Mitchell , d e e a Satoshi Shimano , Olga V. Smirnova , Alexey A. Aleynikov , Yuri A. Mazei aDepartment of Zoology and Ecology, Penza State University, Krasnaya str. 40, 440026 Penza, Russia bLaboratory of Soil Biology, Institute of Biology, University of Neuchâtel, rue Emile Argand 11, CH-2000 Neuchâtel, Switzerland cJardin Botanique de Neuchâtel, Pertuis-du-Sault 56-58, CH-2000 Neuchâtel, Switzerland dScience Research Center, Hosei University, 2-17-1 Fujimi, Chiyoda-ku, 102-8160 Tokyo, Japan eLaboratory of Structural and Functional Organisation of Forest Ecosystems, Center for Problems of Ecology and Productivity of Forests, Russian Academy of Sciences, Profsoyuznaya str. 84/32, 117997 Moscow, Russia Abstract In order to better understand the distribution patterns of terrestrial eukaryotic microbes and the factors governing them, we studied the diversity partitioning of soil testate amoebae across levels of spatially nested habitat hierarchy in the largest European old-growth dark coniferous forest (Pechora-Ilych Biosphere Reserve; Komi Republic, Russia). The variation in testate amoeba species richness and assemblage structure was analysed in 87 samples from six biotopes in six vegetation types using an additive partitioning procedure and principal component analyses. The 80 taxa recorded represent the highest value of species richness for soil testate amoebae reported for taiga soils so far. -

Documenting Calcareous Habitats of High Conservation Value In

DOCUMENTING CALCAREOUS HABITATS OF HIGH CONSERVATION VALUE IN NORTHERN RIVER VALLEYS David Mazerolle, Sean Blaney, Colin Chapman, Alain Belliveau and Tom Neily March 31, 2019 A report to the New Brunswick Wildlife Trust Fund by the Atlantic Canada Conservation Data Centre P.O. Box 6416, Sackville, NB, E4L 1C6 www.accdc.com 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Funding for this project was entirely provided by the New Brunswick Wildlife Trust Fund and Environment and Climate Change Canada’s Atlantic Ecosystems Initiatives funding program. The Atlantic Canada Conservation Data Centre appreciates the opportunity to have carried out surveys in these biologically diverse and provincially significant sites. 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY River valleys are especially diverse portions of any landscape because of their diversity of moisture, exposure and disturbance regimes. In highly altered landscapes, river valleys also often retain the most natural communities because of inherent difficulties in farming, logging and settling their steep slopes and flood-prone bottomlands. Because soils with higher pH values (i.e. alkaline, basic or calcareous soils) are generally much more fertile than acidic ones and often support species- rich communities, river valleys underlain by alkaline bedrock often constitute particularly significant reservoirs of biodiversity. In New Brunswick, high-pH habitats (including alkaline bedrock outcrops, cliffs, fens and swamps) represent a small portion of the provincial land area, often occurring as small islands within a predominantly acidic landscape. These habitats support many of the province’s rarest vascular plant, lichen and bryophyte species and represent areas of high conservation significance. Due to lack of connectivity and relative isolation, species of conservation concern found in these habitats may be at greater risk of local extirpation due to human disturbance or stochastic events, as recruitment and recolonization from other populations is unlikely. -

Digital Compilation of Vegetation Types of the Mackenzie Valley Transportation Corridor

GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF CANADA OPEN FILE 1614 Digital Compilation of Vegetation Types of the Mackenzie Valley Transportation Corridor J.F. Wright, C. Duchesne and M.M. Côté 2003 ©Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada 2002 Available from Geological Survey of Canada 601 Booth Street Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0E8 J.F. Wright, C. Duchesne and M.M. Côté 2003: Digital compilation of vegetation types of the Mackenzie Valley Transportation Corridor; Geological Survey of Canada, Open File 1614, 1 CD-ROM. Open files are products that have not gone through the GSC formal publication process. ABSTRACT The vegetation maps were originally prepared by the Forest Management Institute of the Canadian Forestry Service for the Environmental-Social Program of the Task Force on Northern Oil Development. They were subsequently digitized by Natural Resources Canada (Geological Survey of Canada) for use in a ground thermal modeling project. Secondary benefit of digitizing the 1974 paper maps was data preservation to a digital format easily accessible in a Geographic Information System. The data represent a broad classification of the vegetation in the Mackenzie Valley Transportation Corridor, which stretches along the Mackenzie River, Northwest Territories, from the Alberta border to the Beaufort Sea (10° of latitude). Included in the dataset are information on species composition, and canopy height and density of the forest cover. Landform modifiers are also included for areas of tundra vegetation. The vegetation was interpreted from black and white panchromatic aerial photographs taken between 1970 and 1972. Additional infrared colour photography was taken in 1971 and 1972 to cover a small portion of the area.