FRANK MILLER's IDEALS of HEROISM Stephen Matthew Jones Submitted to the Faculty of the University Graduate School in Partial F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS American Comics SETH KUSHNER Pictures

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL From the minds behind the acclaimed comics website Graphic NYC comes Leaping Tall Buildings, revealing the history of American comics through the stories of comics’ most important and influential creators—and tracing the medium’s journey all the way from its beginnings as junk culture for kids to its current status as legitimate literature and pop culture. Using interview-based essays, stunning portrait photography, and original art through various stages of development, this book delivers an in-depth, personal, behind-the-scenes account of the history of the American comic book. Subjects include: WILL EISNER (The Spirit, A Contract with God) STAN LEE (Marvel Comics) JULES FEIFFER (The Village Voice) Art SPIEGELMAN (Maus, In the Shadow of No Towers) American Comics Origins of The American Comics Origins of The JIM LEE (DC Comics Co-Publisher, Justice League) GRANT MORRISON (Supergods, All-Star Superman) NEIL GAIMAN (American Gods, Sandman) CHRIS WARE SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER (Jimmy Corrigan, Acme Novelty Library) PAUL POPE (Batman: Year 100, Battling Boy) And many more, from the earliest cartoonists pictures pictures to the latest graphic novelists! words words This PDF is NOT the entire book LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS: The Origins of American Comics Photographs by Seth Kushner Text and interviews by Christopher Irving Published by To be released: May 2012 This PDF of Leaping Tall Buildings is only a preview and an uncorrected proof . Lifting -

Representing Heroes, Villains and Anti- Heroes in Comics and Graphic

H-Film CFP: Who’s Bad? Representing Heroes, Villains and Anti- Heroes in Comics and Graphic Narratives – A seminar sponsored by the ICLA Research Committee on Comic Studies and Graphic Narratives Discussion published by Angelo Piepoli on Wednesday, September 7, 2016 This is a Call for Papers for a proposed seminar to be held as part of the American Comparative Literature Association's 2017 Annual Meeting. It will take place at Utrecht University in Utrecht, the Netherlands on July 6-9, 2017. Submitters are required to get a free account on the ACLA's website at http://www.acla.org/user/register . Abstracts are limited to 1500 characters, including spaces. If you wish to submit an astract, visit http://www.acla.org/node/12223 . The deadline for paper submission is September 23, 2016. Since the publication of La vida de Lazarillo de Tormes y de sus fortuna y adversidades in 1554, the figure of the anti-hero, which had originated in Homeric literature, has had great literary fortune over the centuries. Satan as the personification of evil, then, was the most interesting character in Paradise Lost by John Milton and initiated a long series of fascinating literary villains. It is interesting to notice that, in a large part of the narratives of these troubled times we are living in, the protagonist of the story is everything but a hero and the most acclaimed characters cross the moral borders quite frequently. This is a fairly common phenomenon in literature as much as in comics and graphic narratives. The advent of the Modern Age of Comic Books in the U.S. -

A ADVENTURE C COMEDY Z CRIME O DOCUMENTARY D DRAMA E

MOVIES A TO Z MARCH 2021 Ho u The 39 Steps (1935) 3/5 c Blondie of the Follies (1932) 3/2 Czechoslovakia on Parade (1938) 3/27 a ADVENTURE u 6,000 Enemies (1939) 3/5 u Blood Simple (1984) 3/19 z Bonnie and Clyde (1967) 3/30, 3/31 –––––––––––––––––––––– D ––––––––––––––––––––––– –––––––––––––––––––––– ––––––––––––––––––––––– c COMEDY A D Born to Love (1931) 3/16 m Dancing Lady (1933) 3/23 a Adventure (1945) 3/4 D Bottles (1936) 3/13 D Dancing Sweeties (1930) 3/24 z CRIME a The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1960) 3/23 P c The Bowery Boys Meet the Monsters (1954) 3/26 m The Daughter of Rosie O’Grady (1950) 3/17 a The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) 3/9 c Boy Meets Girl (1938) 3/4 w The Dawn Patrol (1938) 3/1 o DOCUMENTARY R The Age of Consent (1932) 3/10 h Brainstorm (1983) 3/30 P D Death’s Fireworks (1935) 3/20 D All Fall Down (1962) 3/30 c Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961) 3/18 m The Desert Song (1943) 3/3 D DRAMA D Anatomy of a Murder (1959) 3/20 e The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957) 3/27 R Devotion (1946) 3/9 m Anchors Aweigh (1945) 3/9 P R Brief Encounter (1945) 3/25 D Diary of a Country Priest (1951) 3/14 e EPIC D Andy Hardy Comes Home (1958) 3/3 P Hc Bring on the Girls (1937) 3/6 e Doctor Zhivago (1965) 3/18 c Andy Hardy Gets Spring Fever (1939) 3/20 m Broadway to Hollywood (1933) 3/24 D Doom’s Brink (1935) 3/6 HORROR/SCIENCE-FICTION R The Angel Wore Red (1960) 3/21 z Brute Force (1947) 3/5 D Downstairs (1932) 3/6 D Anna Christie (1930) 3/29 z Bugsy Malone (1976) 3/23 P u The Dragon Murder Case (1934) 3/13 m MUSICAL c April In Paris -

A Lowell Tax Rate Held at 8 Mills

« a as v> from The lated • ing, ^ Established June. 1893 LOWELL, MICH., THURSDAY, APRIL 25. 1957 Number I dairy tionr UP' Set Budget for Coming Year Home Demonstration lr8 Wescott Wont to Trove! West Come Home With a Fist Full of Ribbons Week April 28-Moy4 Charles HacFariaoe '> - But No Money ? Enjoy Lowell Tax Rate Held at 8 Mills - Accepts Job as Mason Travelog Tonight Area Offers Do Well at Caledonia | Women play a vital role in main- Stricken Monday Village Hostess Ever want to visit the beautiful j WiH Cover Street Repair Work t it Marian Wescott of 319 North national parks of the great North-j Southeast District Achievement Day hem s0,v ,he fm)b erT of ,ho A special meeting of the village i the village for the year was set j ' i f ' J^ At Flour MiU west, the Black Hills. Feton, Mt.. ,\rra 4H club members came [Garry Schmidt earned white rib- famil nrd st. has accepted the job as Lowell council on Monday night set the at 175.300 about 20 per cent higher, y «>"-"unity Homo de- Rainier. \ ellowstone, G 1 a c 1 e r. home, from Caledonia Saturday, bons. monstration work is designed to Village Hostess, replacing Glad village tax rate for 1»57 at 8 than the previous year. Bergin who is retiring because of OKropia Crater Lake and other April'20. aftor the twtwiay South- Mra E. Wlckstead. club loader f meet that need, declares Eleanor! mills, the same as the 1956 ra r. breathtaking nature miracles ol put r let Achiovement of the Sore Thumbers, stated her William Jones, chairman of the Dens mo re, county home demon- commitments which she has made rilst 4n The budget for the operation of finance committee, listed the fol- for the coming months. -

Download Sin City Volume 5 Family Values 3Rd Edition Pdf Ebook by Frank Miller

Download Sin City Volume 5 Family Values 3rd Edition pdf ebook by Frank Miller You're readind a review Sin City Volume 5 Family Values 3rd Edition ebook. To get able to download Sin City Volume 5 Family Values 3rd Edition you need to fill in the form and provide your personal information. Book available on iOS, Android, PC & Mac. Gather your favorite books in your digital library. * *Please Note: We cannot guarantee the availability of this book on an database site. Ebook Details: Original title: Sin City Volume 5: Family Values (3rd Edition) 128 pages Publisher: Dark Horse Books; 2nd Revised ed. edition (November 9, 2010) Language: English ISBN-10: 159307297X ISBN-13: 978-1593072971 Product Dimensions:6 x 0.4 x 9 inches File Format: PDF File Size: 3847 kB Description: Frank Millers first—ever original graphic novel is one of Sin Citys nastiest yarns to date! Starring fan—favorite characters Dwight and Miho, this newly redesigned edition sports a brand—new cover by Miller, some of his first comics art in years!Theres a kind of debt you cant ever pay off, not entirely. And thats the kind of debt Dwight owes Gail.... Review: Family Values is the 5th book in the fantastic Sin City series of graphic novels written and illustrated by mad comic book genius Frank Miller. Its a brief and uncharacteristically straightforward jaunt starring Basin Citys premiere anti-hero Dwight and the biggest/smallest bada$z ever to hit the pulp, deadly little Miho. Sin City began once Miller... Ebook File Tags: sin city pdf, yellow bastard pdf, frank miller pdf, -

Stardigio Program

スターデジオ チャンネル:450 洋楽アーティスト特集 放送日:2019/12/09~2019/12/15 「番組案内 (8時間サイクル)」 開始時間:4:00~/12:00~/20:00~ 楽曲タイトル 演奏者名 ■KISS 特集 (1) STRUTTER KISS NOTHIN' TO LOSE KISS FIREHOUSE KISS COLD GIN KISS LET ME KNOW KISS KISSIN' TIME KISS DEUCE KISS 100,000 YEARS [10万年の彼方] KISS BLACK DIAMOND KISS GOT TO CHOOSE KISS PARASITE KISS GOIN' BLIND KISS HOTTER THAN HELL KISS Let Me Go, Rock 'N' Roll KISS ALL THE WAY KISS WATCHIN' YOU KISS COMIN' HOME KISS ■KISS 特集 (2) ROOM SERVICE KISS ROCK BOTTOM KISS C'MON AND LOVE ME [激しい愛を] KISS SHE [彼女] KISS LOVE HER ALL I CAN [すべての愛を] KISS ROCK AND ROLL ALL NITE KISS Detroit Rock City KISS King Of The Night Time World (暗黒の帝王) KISS God Of Thunder (雷神) KISS Flaming Youth (燃えたぎる血気) KISS Shout It Out Loud (狂気の叫び) KISS Beth KISS DO YOU LOVE ME KISS CALLING DR. LOVE (悪魔のドクター・ラヴ) KISS MR. SPEED (情炎!ミスター・スピード) KISS HARD LUCK WOMAN KISS MAKIN' LOVE (果てしなきロック・ファイヤー) KISS ■KISS 特集 (3) I WANT YOU (いかすぜあの娘) KISS TAKE ME (燃える欲望) KISS LADIES ROOM (熱きレディズ・ルーム) KISS I Stole Your Love [愛の謀略] KISS Christine Sixteen KISS Shock Me KISS Tomorrow And Tonight KISS Love Gun KISS Hooligan KISS Plaster Caster KISS Then She Kissed Me KISS ROCKET RIDE KISS I WAS MADE FOR LOVIN' YOU (ラヴィンユーベイビー) KISS 2,000 MAN KISS SURE KNOW SOMETHING KISS MAGIC TOUCH KISS ■KISS 特集 (4) TONIGHT YOU BELONG TO ME PAUL STANLEY MOVE ON PAUL STANLEY HOLD ME, TOUCH ME (THINK OF ME WHEN WE'RE APART) PAUL STANLEY GOODBYE PAUL STANLEY RADIOACTIVE GENE SIMMONS SEE YOU TONITE [今宵のお前] GENE SIMMONS LIVING IN SIN [罪] GENE SIMMONS WHEN YOU WISH UPON A STAR [星に願いを] GENE SIMMONS RIP IT -

Give Me Liberty!

CHAPTER 18 1889 Jane Addams founds Hull House 1898 Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Women and Economics 1900 Theodore Dreiser’s Sister Carrie 1901 President McKinley assassinated Socialist Party founded in United States 1902 President Theodore Roosevelt assists in the coal strike 1903 Women’s Trade Union League founded 1904 Lincoln Steffen’s The Shame of the Cities Ida Tarbell’s History of the Standard Oil Company Northern Securities dissolved 1905 Ford Motor Company established Industrial Workers of the World established 1906 Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle Pure Food and Drug Act Meat Inspection Act Hepburn Act John A. Ryan’s A Living Wage 1908 Muller v. Oregon 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Company fire Society of American Indians founded 1912 Theodore Roosevelt organizes the Progressive Party Children’s Bureau established 1913 Sixteenth Amendment ratified Seventeenth Amendment ratified Federal Reserve established 1914 Clayton Act Ludlow Massacre Federal Trade Commission established Walter Lippmann’s Drift and Mastery 1915 Benjamin P. DeWitt’s The Progressive Movement The Progressive Era, 1900–1916 AN URBAN AGE AND A THE POLITICS OF CONSUMER SOCIETY PROGRESSIVISM Farms and Cities Effective Freedom The Muckrakers State and Local Reforms Immigration as a Global Progressive Democracy Process Government by Expert The Immigrant Quest for Jane Addams and Hull House Freedom “Spearheads for Reform” Consumer Freedom The Campaign for Woman The Working Woman Suffrage The Rise of Fordism Maternalist Reform The Promise of Abundance The Idea of Economic An American -

Revue De Recherche En Civilisation Américaine, 6

Revue de recherche en civilisation américaine 6 | 2016 Les femmes et la bande dessinée: autorialités et représentations Women and Comics, Authorships and Representations Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/rrca/723 ISSN : 2101-048X Éditeur David Diallo Référence électronique Revue de recherche en civilisation américaine, 6 | 2016, « Les femmes et la bande dessinée: autorialités et représentations » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 19 décembre 2016, consulté le 16 mars 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/rrca/723 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 16 mars 2020. © Tous droits réservés 1 SOMMAIRE Editorial Amélie Junqua et Céline Mansanti Women Comics Authors in France and Belgium Before the 1970s: Making Them Invisible Jessica Kohn L’autoreprésentation féminine dans la bande dessinée pornographique Irène Le Roy Ladurie Empowered et le pouvoir du fan service Alexandra Aïn Women W.a.R.P.ing Gender in Comics: Wendy Pini’s Elfquest as mixed power fantasy Isabelle L. Guillaume A 21st Century British Comics Community that Ensures Gender Balance Nicola Streeten Hors thème Book review Sabbagh, Daniel. L’égalité par le droit, les paradoxes de la discrimination positive aux Etats- Unis Paris, Economica, collection « Etudes Politiques », 2003 [2007], 458 p. Laure Gillot-Assayag Revue de recherche en civilisation américaine, 6 | 2016 2 Editorial Amélie Junqua and Céline Mansanti 1 Aux Etats-Unis, les utilisatrices de Facebook représentent aujourd’hui 53% des utilisateurs de Facebook qui lisent de la bande dessinée, 40% de plus qu’il y a trois ans. Pourtant, moins de 30% des personnages et des écrivains de BD sont des femmes, même si ces chiffres progressent également (http://www.ozy.com/acumen/the-rise-of-the- woman-comic-buyer/63314). -

“Why So Serious?” Comics, Film and Politics, Or the Comic Book Film As the Answer to the Question of Identity and Narrative in a Post-9/11 World

ABSTRACT “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD by Kyle Andrew Moody This thesis analyzes a trend in a subgenre of motion pictures that are designed to not only entertain, but also provide a message for the modern world after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. The analysis provides a critical look at three different films as artifacts of post-9/11 culture, showing how the integration of certain elements made them allegorical works regarding the status of the United States in the aftermath of the attacks. Jean Baudrillard‟s postmodern theory of simulation and simulacra was utilized to provide a context for the films that tap into themes reflecting post-9/11 reality. The results were analyzed by critically examining the source material, with a cultural criticism emerging regarding the progression of this subgenre of motion pictures as meaningful work. “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Communications Mass Communications Area by Kyle Andrew Moody Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2009 Advisor ___________________ Dr. Bruce Drushel Reader ___________________ Dr. Ronald Scott Reader ___________________ Dr. David Sholle TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .......................................................................................................................... III CHAPTER ONE: COMIC BOOK MOVIES AND THE REAL WORLD ............................................. 1 PURPOSE OF STUDY ................................................................................................................................... -

A Dark, Uncertain Fate: Homophobia, Graphic Novels, and Queer

A DARK, UNCERTAIN FATE: HOMOPHOBIA, GRAPHIC NOVELS, AND QUEER IDENTITY By Michael Buso A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, Florida May 2010 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis would not have been possible without the fundamental assistance of Barclay Barrios, the hours of office discourse with Eric Berlatsky, and the intellectual analysis of Don Adams. The candidate would also like to thank Robert Wertz III and Susan Carter for their patience and support throughout the writing of this thesis. iii ABSTRACT Author: Michael Buso Title: A Dark, Uncertain Fate: Homophobia, Graphic Novels, and Queer Identity Institution: Florida Atlantic University Thesis Advisor: Dr. Barclay Barrios Degree: Master of Arts Year: 2010 This thesis focuses primarily on homophobia and how it plays a role in the construction of queer identities, specifically in graphic novels and comic books. The primary texts being analyzed are Alan Moore’s Lost Girls, Frank Miller’s Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, and Michael Chabon’s prose novel The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay. Throughout these and many other comics, queer identities reflect homophobic stereotypes rather than resisting them. However, this thesis argues that, despite the homophobic tendencies of these texts, the very nature of comics (their visual aspects, panel structures, and blank gutters) allows for an alternative space for positive queer identities. iv A DARK, UNCERTAIN FATE: HOMOPHOBIA, GRAPHIC NOVELS, AND QUEER IDENTITY TABLE OF FIGURES ....................................................................................................... vi I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... 1 Theoretical Framework .................................................................................................. -

Costume Culture: Visual Rhetoric, Iconography, and Tokenism In

COSTUME CULTURE: VISUAL RHETORIC, ICONOGRAPHY, AND TOKENISM IN COMIC BOOKS A Dissertation by MICHAEL G. BAKER Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies Texas A&M University-Commerce in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2017 COSTUME CULTURE: VISUAL RHETORIC, ICONOGRAPHY, AND TOKENISM IN COMIC BOOKS A Dissertation by MICHAEL G. BAKER Submitted to: Advisor: Christopher Gonzalez Committee: Tabetha Adkins Donna Dunbar-Odom Mike Odom Head of Department: M. Hunter Hayes Dean of the College: Salvatore Attardo Interim Dean of Graduate Studies: Mary Beth Sampson iii Copyright © 2017 Michael G. Baker iv ABSTRACT COSTUME CULTURE: VISUAL RHETORIC, ICONOGRAPHY, AND TOKENISM IN COMIC BOOKS Michael G. Baker, PhD Texas A&M University-Commerce, 2017 Advisor: Christopher Gonzalez, PhD Superhero comic books provide a unique perspective on marginalized characters not only as objects of literary study, but also as opportunities for rhetorical analysis. There are representations of race, gender, sexuality, and identity in the costuming of superheroes that impact how the audience perceives the characters. Because of the association between iconography and identity, the superhero costume becomes linked with the superhero persona (for example the Superman “S” logo is a stand-in for the character). However, when iconography is affected by issues of tokenism, the rhetorical message associated with the symbol becomes more difficult to decode. Since comic books are sales-oriented and have a plethora of tie-in merchandise, the iconography in these symbols has commodified implications for those who choose to interact with them. When consumers costume themselves with the visual rhetoric associated with comic superheroes, the wearers engage in a rhetorical discussion where they perpetuate whatever message the audience places on that image. -

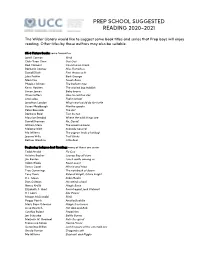

Prep School Suggested Reading 2020-2021

PREP SCHOOL SUGGESTED READING 2020-2021 The Wilder Library would like to suggest some book titles and series that Prep boys will enjoy reading. Other titles by these authors may also be suitable. SK-3 Picture Books: some favourites Janell Cannon Verdi Chih-Yuan Chen Guji Guji Rod Clement Counting on Frank Barbara Cooney Miss Rumphius David Elliott Finn throws a fit Jules Feiffer Bark George Mem Fox Tough Boris Phoebe Gilman The balloon tree Kevin Hawkes The wicked big toddlah Simon James Baby brains Oliver Jeffers How to catch a star Lita Judge Flight School Jonathan London What newt could do for turtle Susan Meddaugh Martha speaks Peter Reynolds The dot Barbara Reid Two by two Maurice Sendak Where the wild things are David Shannon No, David! William Steig The amazing bone Melanie Watt Scaredy Squirrel Mo Willems The pigeon finds a hotdog! Jeanne Willis Troll Stinks Bethan Woollvin Little Red Beginning Independent Reading: many of these are series Tedd Arnold Fly Guy Helaine Becker Looney Bay all stars Jim Benton Lunch walks among us Adam Blade Beast quest Denys Cazet Minnie and Moo Troy Cummings The notebook of doom Tony Davis Roland Wright, future knight D.L. Green Zeke Meeks Dan Gutman My weird school Nancy Krulik Magic Bone Elizabeth S. Hunt Secret agent Jack Stalwart H.I. Larry Zac Power Megan McDonald Stink Peggy Parish Amelia Bedelia Mary Pope Osborne Magic tree house Lissa Rovetch Hot dog and Bob Cynthia Rylant Poppleton Jon Scieszka Battle Bunny Marjorie W. Sharmat Nate the great Francesca Simon Horrid Henry Geronimo Stilton Lost treasure of the emerald eye Ursula Vernon Dragonbreath Mo Willems Elephant and Piggie SK-3 Novels: for reading aloud, reading together, or reading independently Richard Atwater Mr.