Identification of American Chestnut Trees

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Chestnut Blight Fungus for Studies on Virus/Host and Virus/Virus Interactions: from a Natural to a Model Host

Virology 477 (2015) 164–175 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Virology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/yviro The chestnut blight fungus for studies on virus/host and virus/virus interactions: From a natural to a model host Ana Eusebio-Cope a, Liying Sun b, Toru Tanaka a, Sotaro Chiba a, Shin Kasahara c, Nobuhiro Suzuki a,n a Institute of Plant Science and Resources (IPSR), Okayama University, Chuou 2-20-1, Kurashiki, Okayama 710-0046, Japan b College of Plant Protection, Northwest A & F University, Yangling, Shananxi, China c Department of Environmental Sciences, Miyagi University, Sendai 982-215, Japan article info abstract Article history: The chestnut blight fungus, Cryphonectria parasitica, is an important plant pathogenic ascomycete. The Received 16 August 2014 fungus hosts a wide range of viruses and now has been established as a model filamentous fungus for Returned to author for revisions studying virus/host and virus/virus interactions. This is based on the development of methods for 15 September 2014 artificial virus introduction and elimination, host genome manipulability, available host genome Accepted 26 September 2014 sequence with annotations, host mutant strains, and molecular tools. Molecular tools include sub- Available online 4 November 2014 cellular distribution markers, gene expression reporters, and vectors with regulatable promoters that Keywords: have been long available for unicellular organisms, cultured cells, individuals of animals and plants, and Cryphonectria parasitica certain filamentous fungi. A comparison with other filamentous fungi such as Neurospora crassa has been Chestnut blight fungus made to establish clear advantages and disadvantages of C. parasitica as a virus host. In addition, a few dsRNA recent studies on RNA silencing vs. -

NDP 11 V2 - National Diagnostic Protocol for Cryphonectria Parasitica

NDP 11 V2 - National Diagnostic Protocol for Cryphonectria parasitica National Diagnostic Protocol Chestnut blight Caused by Cryphonectria parasitica NDP 11 V2 NDP 11 V2 - National Diagnostic Protocol for Cryphonectria parasitica © Commonwealth of Australia Ownership of intellectual property rights Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia (referred to as the Commonwealth). Creative Commons licence All material in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence, save for content supplied by third parties, logos and the Commonwealth Coat of Arms. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided you attribute the work. A summary of the licence terms is available from http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en. The full licence terms are available from https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/legalcode. This publication (and any material sourced from it) should be attributed as: Subcommittee on Plant Health Diagnostics (2017). National Diagnostic Protocol for Cryphonectria parasitica – NDP11 V2. (Eds. Subcommittee on Plant Health Diagnostics) Authors Cunnington, J, Mohammed, C and Glen, M. Reviewers Pascoe, I and Tan YP, ISBN 978-0- 9945113-6-2. CC BY 3.0. Cataloguing data Subcommittee on Plant Health Diagnostics (2017). National Diagnostic Protocol for Cryphonectria parasitica – NDP11 V2. (Eds. Subcommittee on Plant Health Diagnostics) Authors Cunnington, J, Mohammed, C and Glen, M. Reviewers Pascoe, I and Tan YP, ISBN 978-0-9945113-6-2. -

Restoration of the American Chestnut in New Jersey

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Restoration of the American Chestnut in New Jersey The American chestnut (Castanea dentata) is a tree native to New Jersey that once grew from Maine to Mississippi and as far west as Indiana and Tennessee. This tree with wide-spreading branches and a deep broad-rounded crown can live 500-800 years and reach a height of 100 feet and a diameter of more than 10 feet. Once estimated at 4 billion trees, the American chestnut Harvested chestnuts, early 1900's. has almost been extirpated in the last 100 years. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, New Jersey Field Value Office (Service) and its partners, including American Chestnut The American chestnut is valued Cooperators’ Foundation, American for its fruit and lumber. Chestnuts Chestnut Foundation, Monmouth are referred to as the “bread County Parks, Bayside State tree” because their nuts are Prison, Natural Lands Trust, and so high in starch that they can several volunteers, are working to American chestnut leaf (4"-8"). be milled into flour. Chestnuts recover the American chestnut in can be roasted, boiled, dried, or New Jersey. History candied. The nuts that fell to the ground were an important cash Chestnuts have a long history of crop for families in the northeast cultivation and use. The European U.S. and southern Appalachians chestnut (Castanea sativa) formed up until the twentieth century. the basis of a vital economy in Chestnuts were taken into towns the Mediterranean Basin during by wagonload and then shipped Roman times. More recently, by train to major markets in New areas in Southern Europe (such as York, Boston, and Philadelphia. -

UNIVERSITY of WISCONSIN-LA CROSSE Graduate Studies

UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN-LA CROSSE Graduate Studies BIOLOGICAL CONTROL OF CRYPHONECTRIA PARASITICA WITH STREPTOMYCES AND AN ANALYSIS OF VEGETATIVE COMPATIBILITY DIVERSITY OF CRYPHONECTRIA PARASITICA IN WISCONSIN, USA. A Manuscript Style Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Biology Ashley R. Smith College of Science and Allied Health Biology December, 2013 ABSTRACT Smith, A.S. Biological control of Cryphonectria parasitica with Streptomyces and an analysis of vegetative compatibility diversity of Cryphonectria parasitica in Wisconsin, USA. MS in Biology, December 2013, 52pp. (A. Baines) The American chestnut tree (Castanea dentata) has been plagued by the fungal pathogen Cryphonectria parasitica. While the primary biological control treatment has relied upon the use of hypovirus, a mycovirus that reduces the virulence of C. parasitica, here the potential for a Streptomyces inoculum as a biological control is explored. Two Wisconsin stands of infected chestnut in Galesville and Rockland were inoculated with hypovirus and Streptomyces using a randomized block design. At these stands the Streptomyces treatment reduced canker length expansion rates more than the hypovirus treatments and control. The Streptomyces treatment had significantly lower canker width expansion rates compared to the control. In addition to having reduced canker expansion rates, the trees inoculated with Streptomyces had the lowest mortality rate. The diversity of the fungus was low at the study sites and consisted of only two known vegetative compatibility types at each stand. This low level of diversity made it ideal for hypovirus dispersal, and for limiting canker expansion rates. This research supports the hypothesis that Streptomyces treatment is an effective alternative to hypovirus treatment that may prove beneficial in areas where hypovirus efforts have failed. -

Chestnuts Bred for Blight Resistance Depart Nursery with Distinct Fungal Rhizobiomes

Mycorrhiza (2019) 29:313–324 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00572-019-00897-z ORIGINAL ARTICLE Chestnuts bred for blight resistance depart nursery with distinct fungal rhizobiomes Christopher Reazin1 & Richard Baird2 & Stacy Clark3 & Ari Jumpponen1 Received: 15 January 2019 /Accepted: 9 May 2019 /Published online: 25 May 2019 # Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature 2019 Abstract Restoration of the American chestnut (Castanea dentata) is underway using backcross breeding that confers chestnut blight disease resistance from Asian chestnuts (most often Castanea mollissima) to the susceptible host. Successful restoration will depend on blight resistance and performance of hybrid seedlings, which can be impacted by below-ground fungal communities. We compared fungal communities in roots and rhizospheres (rhizobiomes) of nursery-grown, 1-year-old chestnut seedlings from different genetic families of American chestnut, Chinese chestnut, and hybrids from backcross breeding generations as well as those present in the nursery soil. We specifically focused on the ectomycorrhizal (EcM) fungi that may facilitate host performance in the nursery and aid in seedling establishment after outplanting. Seedling rhizobiomes and nursery soil communities were distinct and seedlings recruited heterogeneous communities from shared nursery soil. The rhizobiomes included EcM fungi as well as endophytes, putative pathogens, and likely saprobes, but their relative proportions varied widely within and among the chestnut families. Notably, hybrid seedlings that hosted few EcM fungi hosted a large proportion of potential pathogens and endophytes, with possible consequences in outplanting success. Our data show that chestnut seedlings recruit divergent rhizobiomes and depart nurseries with communities that may facilitate or compromise the seedling performance in the field. -

The Effect of Insects on Seed Set of Ozark Chinquapin, Castanea Ozarkensis" (2017)

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 5-2017 The ffecE t of Insects on Seed Set of Ozark Chinquapin, Castanea ozarkensis Colton Zirkle University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Botany Commons, Entomology Commons, and the Plant Biology Commons Recommended Citation Zirkle, Colton, "The Effect of Insects on Seed Set of Ozark Chinquapin, Castanea ozarkensis" (2017). Theses and Dissertations. 1996. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/1996 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. The Effect of Insects on Seed Set of Ozark Chinquapin, Castanea ozarkensis A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Entomology by Colton Zirkle Missouri State University Bachelor of Science in Biology, 2014 May 2017 University of Arkansas This thesis is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. ____________________________________ Dr. Ashley Dowling Thesis Director ____________________________________ ______________________________________ Dr. Frederick Paillet Dr. Neelendra Joshi Committee Member Committee Member Abstract Ozark chinquapin (Castanea ozarkensis), once found throughout the Interior Highlands of the United States, has been decimated across much of its range due to accidental introduction of chestnut blight, Cryphonectria parasitica. Efforts have been made to conserve and restore C. ozarkensis, but success requires thorough knowledge of the reproductive biology of the species. Other Castanea species are reported to have characteristics of both wind and insect pollination, but pollination strategies of Ozark chinquapin are unknown. -

Emerald Ash Borer and Other Invasives: the Colorado Experience

Emerald ash borer and other invasives: The Colorado Experience Sentinel Plant Workshop July 17, 2019 Whitney Cranshaw Colorado State University Emerald ash borer (EAB) is a green- colored beetle……. …that develops in ash trees (Fraxinus species)… ……and is Native to Asia Larvae tunnel under the bark girdling the cambium. Photo by Edward Czerwinski Effects of larval tunneling are cumulative, and ultimately lethal to the tree. Most trees are dead within 5 years after the initial colonization. Photograph by MI Department of Agriculture Emerald ash borer was accidentally introduced into and has since spread through North America First NA detection 2002 Lilac/Ash Borer does not equal Emerald Ash Borer! Lilac/ash borer, a clearwing borer moth Emerald ash borer, a metallic wood borer/ flatheaded borer Emerald ash borer is a wood boring beetle inEmerald the family B ash borer Agrilus plannipennis Photograph by Debbie Miller Order Coleoptera (beetles) Family Buprestidae (metallic wood borers, flatheaded borers) Photograph by David Cappaert Emerald ash borer larvae create meandering tunnels in the cambium that produce girdling wounds. Note: Attacks can occur throughout the crown and on the trunk of the tree. Photograph by Eric Day EAB adults chew through the bark, producing D-shaped exit holes Damage potential to its host 10 – EAB now defines an aggressive tree killing insect in North America. Emerald ash borer is devastating to all species of ash that are native to North America Green ash White ash No EAB Resistance Why is EAB so destructive to ash trees in North America? NA ash species lack ability to ability to resist EAB No EAB Resistance Common question: How is this different from mountain pine beetle? MPB killed a lot of trees. -

Summer 2018 Newsletter the Ecoforester Invasive Species Edition

SUMMER 2018 NEWSLETTER THE ECOFORESTER NVASIVE PECIES DITION I S E Novel Ecosystems: Forestry and Invasive Species Management Many Appalachian forests now have well established assemblages of invasive exotic plants, sometimes a dozen species or more, including trees, vines, shrubs, and herbaceous plants. In these unprecedented plant communities, referred to as “novel ecosystems”, invasive plant eradication is not practical. Our challenge lies in containing invasives within these novel ecosystems, minimizing their spread and impact on native species, while overall sustaining a healthy vibrant Appalachian forest. To achieve these goals, a strategic approach is needed to maximize positive-impact from the limited resources available to combat invasives species. This is especially true when timber harvests or other disturbances can create additional opportunities for invasive plants to spread. Forestlands owned by the Biltmore Estate in Asheville exemplify a novel ecosystem, with at least 10 non-native invasive species well Inside This Issue established inside a native forest canopy of white pine, white oak, and yellow poplar. This past winter, EcoForesters was hired by the Biltmore Announcing Our Boone Office & Estate to conduct a sustainable timber harvest within 100 acres of this novel ecosystem. Biltmore’s objectives were to sustain forest ecological A New Face of EcoForesters... 2 health, but also to generate revenue from the sale of timber and to maintain aesthetics for pedestrian and equestrian users. In determining the EcoForesters’ 7 P’s for Invasive best course of action, EcoForesters devised 7 simple principles, the 7 P’s Plant Management........................ 3 of invasives control (see side bar on page 3), to guide our approach towards meeting Biltmore’s objectives. -

This Article Is from the August 2011 Issue of Published by the American

This article is from the August 2011 issue of published by The American Phytopathological Society For more information on this and other topics related to plant pathology, we invite you to visit APSnet at www.apsnet.org Oak wilt, caused by the fungus Ceratocystis fagacearum (Bretz) Taxonomy, Occurrence, and Significance of Oaks J. Hunt, is an important disease of oaks (Quercus spp.) in the east- Quercus (Family Fagaceae), commonly referred to as oaks, is a ern United States. It has been particularly destructive in the North large genus of trees and shrubs, containing over 400 species world- Central states and Texas. Oak wilt is one of several significant oak wide (67). Relative to the expansive worldwide distribution of diseases that threaten oak health worldwide. The significant gains oaks, oak wilt is known to occur only in part of its potential range made in our knowledge of the biology and epidemiology of this in the United States. Further, C. fagacearum is pathogenic only to vascular wilt disease during the past six decades has led to devel- certain groups within the large variety of oak species. With the opment of various management strategies. exception of Lithocarpus, differences in the fruit (acorns) of Quer- Interest in oak wilt research and management has “waxed and cus spp. serve to distinguish the oaks from other taxa in the Fa- waned” since the pathogen was initially discovered in the early gaceae (the beech family) (67). Taxonomically, Quercus currently 1940s (61). This ambivalence, accompanied by emphasis on newly is divided into four sections: Section Cerris with species in Asia, emerging oak diseases such as sudden oak death (107) and Raf- Europe, and the Mediterranean; Section Lobatae, or red oaks, faelea-caused wilt of oaks in Japan and Korea (82,83), could have found only in the Americas; Section Quercus, or white oaks, with very costly consequences. -

American Chestnut, Castanea Dentata

FORFS 20-03 University of Kentucky College of Agriculture, Food and Environment American Chestnut, Cooperative Extension Service Castanea dentata Megan Buland and Ellen Crocker, Forest Health Extension, and Rick Bennett, Plant Pathology merican chestnut (Castanea den- tata) was once a dominant tree species,A historically found throughout eastern North America and comprising nearly 1 of every 4 trees in the central Ap- palachian region. Valued for its nuts (eat- en by people and a key source of wildlife mast), rot resistance and attractive timber, it was a central component of many east- ern forests (Fig. 1). However, the invasive chestnut blight fungus (Cryphonectria parasitica), introduced to North Amer- ica from Asia in the early 1900s, wiped out the majority of mature American chestnut throughout its range. While American chestnut is still functionally absent from these areas, continued ef- forts to return it to its native range, led by several different non-profit and academic research partners and using a variety of different approaches, are underway and provide hope for restoring this species. Figure 1. Large healthy American chest- Figure 4. Larger trunks and branches have nuts like this, once valued for timber, are deep vertical furrows. Species Characteristics now very rare. Most succumb to chestnut blight when they are much younger. American chestnut is a member of the Photos courtesies: Figure 1: USDA Forest Service - Southern Research Station, USDA Forest Service, Fagaceae family, the same family to SRS, Bugwood.org; Figure 4: Megan Buland, University of Kentucky which oak and beech trees belong. The leaves and branches of American chest- oblong in shape, 5-8” long, with a coarsely serrated margin, each serration ending in nut are alternate in arrangement (Fig. -

Is Emerald Ash Borer the Next Chestnut Blight?

Cass County | 8400 144th Street, Suite 100 | Weeping Water, NE 68463 | 402-267-2205 | http://cass.unl.edu Is Emerald Ash Borer the Next Chestnut Blight? "Chestnuts roasting on an open fire, Jack Frost nipping at your nose….” We’re all familiar with this popular holiday song, but have you ever wondered how to roast chestnuts? Or exactly what a chestnut tree looks like? Why don't we see them growing in our neighborhoods? Once, American chestnut was a major component of eastern forests from Maine to Michigan and south to Alabama and Mississippi. Called the ‘Redwood of the East’ because of the tremendous size of mature trees, American chestnuts made up approximately 25% of forests in the eastern United States. When chestnuts bloomed in spring, the Appalachian mountains appeared covered in snow. The trees were an important part of the rural economy, as a source of highly rot-resistant lumber, and the nuts a major food source for wildlife. Trainloads of chestnuts were sent to eastern cities to be roasted and sold by street vendors during the holidays. However, today the American chestnut has been reduced to merely an under-story shrub in eastern forests. So what happened to this great tree? Chestnut canker or blight, Cryphonectria parasitic, was the culprit, an Asian fungus to which American chestnut had, and to this day has, little resistance. It is likely plant enthusiasts inadvertently brought the fungus into the United States in the late 1800’s on imported plants. The disease was first spotted by sharp-eyed groundskeepers in 1904 killing chestnut trees at the Bronx Zoo in New York City. -

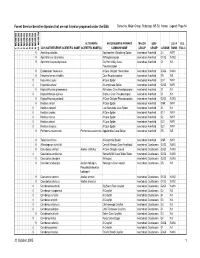

Sensitive Species That Are Not Listed Or Proposed Under the ESA Sorted By: Major Group, Subgroup, NS Sci

Forest Service Sensitive Species that are not listed or proposed under the ESA Sorted by: Major Group, Subgroup, NS Sci. Name; Legend: Page 94 REGION 10 REGION 1 REGION 2 REGION 3 REGION 4 REGION 5 REGION 6 REGION 8 REGION 9 ALTERNATE NATURESERVE PRIMARY MAJOR SUB- U.S. N U.S. 2005 NATURESERVE SCIENTIFIC NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME(S) COMMON NAME GROUP GROUP G RANK RANK ESA C 9 Anahita punctulata Southeastern Wandering Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G4 NNR 9 Apochthonius indianensis A Pseudoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G1G2 N1N2 9 Apochthonius paucispinosus Dry Fork Valley Cave Invertebrate Arachnid G1 N1 Pseudoscorpion 9 Erebomaster flavescens A Cave Obligate Harvestman Invertebrate Arachnid G3G4 N3N4 9 Hesperochernes mirabilis Cave Psuedoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G5 N5 8 Hypochilus coylei A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G3? NNR 8 Hypochilus sheari A Lampshade Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G2G3 NNR 9 Kleptochthonius griseomanus An Indiana Cave Pseudoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G1 N1 8 Kleptochthonius orpheus Orpheus Cave Pseudoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G1 N1 9 Kleptochthonius packardi A Cave Obligate Pseudoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G2G3 N2N3 9 Nesticus carteri A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid GNR NNR 8 Nesticus cooperi Lost Nantahala Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G1 N1 8 Nesticus crosbyi A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G1? NNR 8 Nesticus mimus A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G2 NNR 8 Nesticus sheari A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G2? NNR 8 Nesticus silvanus A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G2? NNR