Before the Environment Court Between

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notes Subscription Agreement)

Amendment and Restatement Deed (Notes Subscription Agreement) PARTIES New Zealand Local Government Funding Agency Limited Issuer The Local Authorities listed in Schedule 1 Subscribers 3815658 v5 DEED dated 2020 PARTIES New Zealand Local Government Funding Agency Limited ("Issuer") The Local Authorities listed in Schedule 1 ("Subscribers" and each a "Subscriber") INTRODUCTION The parties wish to amend and restate the Notes Subscription Agreement as set out in this deed. COVENANTS 1. INTERPRETATION 1.1 Definitions: In this deed: "Notes Subscription Agreement" means the notes subscription agreement dated 7 December 2011 (as amended and restated on 4 June 2015) between the Issuer and the Subscribers. "Effective Date" means the date notified by the Issuer as the Effective Date in accordance with clause 2.1. 1.2 Notes Subscription Agreement definitions: Words and expressions defined in the Notes Subscription Agreement (as amended by this deed) have, except to the extent the context requires otherwise, the same meaning in this deed. 1.3 Miscellaneous: (a) Headings are inserted for convenience only and do not affect interpretation of this deed. (b) References to a person include that person's successors, permitted assigns, executors and administrators (as applicable). (c) Unless the context otherwise requires, the singular includes the plural and vice versa and words denoting individuals include other persons and vice versa. (d) A reference to any legislation includes any statutory regulations, rules, orders or instruments made or issued pursuant to that legislation and any amendment to, re- enactment of, or replacement of, that legislation. (e) A reference to any document includes reference to that document as amended, modified, novated, supplemented, varied or replaced from time to time. -

QUARTERLY INFRASTRUCTURE REFERENCE GROUP UPDATE Q1: to 31 MARCH 2021 QUARTERLY IRG UPDATE 2 Q1: to 31 MARCH 2021

Building Together • Hanga Ngātahi QUARTERLY INFRASTRUCTURE REFERENCE GROUP UPDATE Q1: to 31 MARCH 2021 QUARTERLY IRG UPDATE 2 Q1: to 31 MARCH 2021 IRG PROGRAMME OVERVIEW .....................................3 PROGRESS TO DATE ................................................4 COMPLETED PROJECTS THIS QUARTER ...........................5 REGIONAL SUMMARY .............................................6 UPDATE BY REGION NORTHLAND ........................................................8 AUCKLAND .........................................................9 WAIKATO ...........................................................10 BAY OF PLENTY ....................................................11 GISBORNE ..........................................................12 HAWKE’S BAY ......................................................13 TARANAKI ..........................................................14 CONTENTS MANAWATŪ-WHANGANUI ........................................15 WELLINGTON .......................................................16 TOP OF THE SOUTH ................................................17 WEST COAST .......................................................18 CANTERBURY .......................................................19 OTAGO ..............................................................20 SOUTHLAND ........................................................21 NATIONWIDE .......................................................22 FULL PROJECT LIST ................................................23 GLOSSARY ..........................................................31 -

HRE05002-038.Pdf(PDF, 152

Appendix S: Parties Notified List of tables Table S1: Government departments and Crown agencies notified ........................... 837 Table S2: Interested parties notified .......................................................................... 840 Table S3: Interested Māori parties ............................................................................ 847 Table S1: Government departments and Crown agencies notified Job Title Organisation City Manager Biosecurity Greater Wellington - The Regional Council Masterton 5915 Environment Health Officer Wairoa District Council Wairoa 4192 Ministry of Research, Science & Wellington 6015 Technology (MoRST) Manager, Animal Containment AgResearch Limited Hamilton 2001 Facility Group Manager, Legal AgResearch Limited Hamilton Policy Analyst Human Rights Commission Auckland 1036 Management, Monitoring & Ministry of Pacific Island Affairs Wellington 6015 Governance Fish & Game Council of New Zealand Wellington 6032 Engineer Land Transport Safety Authority Wellington 6015 Senior Fisheries Officer Fish & Game Eastern Region Rotorua 3220 Adviser Ministry of Research, Science & Wellington 6015 Technology (MoRST) Programme Manager Environment Waikato Hamilton 2032 Biosecurity Manager Environment Southland Invercargill 9520 Dean of Science and University of Waikato Hamilton 3240 Technology Director National Institute of Water & Atmospheric Wellington 6041 Research Limited (NIWA) Chief Executive Officer Horticulture and Food Research Institute Auckland 1020 (HortResearch Auckland) Team Leader Regulatory -

Scanned Using Fujitsu 6670 Scanner and Scandall Pro Ver 1.7 Software

961 1989/160 THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT ACT FIRST SCHEDULE ORDER (NO. 2) 1989 PAUL REEVES, Governor·General ORDER IN COUNCIL At Wellington this 12th day of June 1989 Present: HIS EXCELLENCY THE GOVERNOR· GENERAL IN COUNCIL PURSUANT to section 41 of the Local Government Amendment Act (No. 2) 1989, His Excellency the Governor-General, acting by and with the advice and consent of the Executive Council, hereby makes the following order. ORDER 1. Title and cornrnencernent-( 1) This order may be cited as the Local Government Act First Schedule Order (No. 2) 1989. (2) This order shall come into force on the 1st day of November 1989. 2. New First Schedule substituted-The Local Government Act 1974 is hereby amended by revoking the First Schedule, and substituting the First Schedule set out in the Schedule to this order. 3. Revocation-The Local Government Act First Schedule Order 1989" is hereby consequentially revoked. ·S.R. 1989/85 962 Local Government Act First Schedule Order 1989/160 (No. 2) 1989 SCHEDULE NEW FIRST SCHEDULE TO LOCAL GOVERNMENT ACT 1974 "FIRST SCHEDULE LoCAL AUTHORITIES Part I Regional Councils The Auckland Regional Council The Bay of Plenty Regional Council The Canterbury Regional Council The Hawke's Bay Regional Council The Manawatu-Wanganui Regional Council The Nelson-Marlborough Regional Council The Northland Regional Council The Otago Regional Council The Southland Regional Council The Taranaki Regional Council The Waikato Regional Council The Wellington Regional Council The West Coast Regional Council Part 11 District Councils -

ALGIM Member Subscription Service List of Council’S/CCO’S Webinar Subscription Level Pricing Structure

Published June 2021 ALGIM Member Subscription Service List of Council’s/CCO’s webinar subscription level pricing structure NB. Per annual subscription year of 12 months, a minimum of 24 webinars will be included in the subscription fee. If a Council/CCO does not choose to join the subscription service then the following costs will apply per webinar: $125 individual, $300 Whole Council/CCO (excl. GST) Council ALGIM Webinar Annual Subscription Fee Subscription Level 1 Jul 2021 – 30 Jun 2022 (excl. GST) Auckland Council Christchurch City Council 3 $2,285.00 Dunedin City Council Environment Canterbury Greater Wellington Hamilton City Council Hastings District Council Hutt City Council New Plymouth District Council Palmerston North City Council Rotorua Lakes Council Tauranga City Council Waikato Regional Council Waikato District Council Wellington City Council Whangarei District Council Ashburton District Council Bay of Plenty Regional Council 2 $1780.00 Far North District Council Gisborne District Council Great Lake Taupo District Council Horizons Regional Council Horowhenua District Council Invercargill City Council Kapiti Coast District Council Napier City Council Nelson City Council Manawatu District Council Marlborough District Council Matamata Piako District Council Porirua City Council Queenstown Lakes District Council Selwyn District Council South Taranaki District Council Southland District Council Tasman District Council Thames Coromandel District Council Timaru District Council Upper Hutt City Council Waimakariri District Council -

Environmental Scan 2020

Kaipara, Place, People and Key Trends Kaipara District Environmental Scan 2020 KAIPARA DISTRICT ENVIRONMENTAL SCAN 2020 Contents 1 Executive Summary .......................................................................................................... 1 2 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 1 3 Kaipara – Two Oceans, Two Harbours ............................................................................ 2 3.1 Land around the water – our maunga, awa and moana ............................................ 2 3.2 Geology – bones of the landscape ............................................................................ 7 3.3 Soil – foundation of life .............................................................................................. 9 3.4 Weather and climate ................................................................................................ 12 3.5 Climate change ........................................................................................................ 16 3.6 Distribution of Settlement ......................................................................................... 22 4 Demography – Our people, Our communities .............................................................. 23 4.1 Population nationally ................................................................................................ 23 4.2 Population regionally .............................................................................................. -

Community Engagement on Climate Change Adaptation

Community engagement on climate change adaptation Case studies August 2020 Contents Foreword p3 1> Introduction p5 2> What is community engagement? p8 3> The key challenges: common themes emerging from the case studies p11 4> Case Study 1: Kaipara District Council – The Ruawai Flats p13 5> Case Study 2: Christchurch City Council – Southshore and South New Brighton p19 6> Case Study 3: Dunedin City Council – South Dunedin p25 7> Recommendations p30 2 Foreword Community engagement on climate change adaptation 3 Foreword Over the last 12 months, there has been a groundswell of public debate on the need for more action on climate change. From street marches to column inches, there has been no shortage of mainstream focus on climate change. Notable too has been the growing awareness of the need to prepare This is understandable to some degree. Although climate change for the effects climate change will have on our nation. Councils play has been a well-understood threat in scientific and policy circles a critical role in leading this adaptation response. for a number of years, the desire from communities for action has eclipsed the ability of the system to respond, and we are very much The pertinent question for communities, local government and in catch-up mode. central government is how is this being translated into action on climate change, and are our systems well-positioned to enable the This shines through in our case studies, with both councils and change our people want to see? communities calling out for strong national direction, adequate resourcing, clear communication, definition of roles and These are two complex questions, and to answer them Local responsibility, direction around engagement and good partnerships Government New Zealand collaborated with three councils to gain a between local government, central government and the private better understanding of the challenges they face when having tough sector. -

Local Government Leaders' Climate Change Declaration

Local Government Leaders’ Climate Change Declaration In 2015, Mayors and Chairs of New Zealand declared an urgent need for responsive leadership and a holistic approach to climate change. We, the Mayors and Chairs of 2017, wholeheartedly support that call for action. Climate change presents significant opportunities, challenges and risks to communities throughout the world and in New Zealand. Local and regional government undertakes a wide range of activities that will be impacted by climate change and provides infrastructure and services useful in reducing greenhouse gas emissions and enhancing resilience. We have come together, as a group of Mayors and Chairs representing local government from across New Zealand to: 1. acknowledge the importance and urgent need to address climate change for the benefit of current and future generations; 2. give our support to the New Zealand Government for developing and implementing, in collaboration with councils, communities and businesses, an ambitious transition plan toward a low carbon and resilient New Zealand; 3. encourage Government to be more ambitious with climate change mitigation measures; 4. outline key commitments our councils will take in responding to the opportunities and risks posed by climate change; and 5. recommend important guiding principles for responding to climate change. We ask that the New Zealand Government make it a priority to develop and implement an ambitious transition plan for a low carbon and resilient New Zealand. We stress the benefits of early action to moderate the costs of adaptation to our communities. We are all too aware of challenges we face shoring up infrastructure and managing insurance costs. -

East West Link Board of Inquiry New Zealand

EAST WEST LINK BOARD OF INQUIRY NEW ZEALAND TRANSPORT AGENCY BUNDLE OF AUTHORITIES VOLUME 1 Case Law (A-Z) 1. Arrigato Investments Ltd v Auckland Regional Council (2001) 7 ELRNZ 193 (CA). 2. Calveley v Kaipara District Council [2014] NZEnvC 182. 3. Cookson Road Character Preservation Society Inc v Rotorua District Council [2013] NZEnvC 194. 4. Darby v Queenstown Lakes District Council [2007] NZRMA 420 (ENC). 5. Dye v Auckland Regional Council [2002] 1 NZLR 337 (CA). 6. Elderslie Park Ltd v Timaru [1995] NZRMA 433 (HC). 7. Envirofume Ltd v Bay of Plenty Regional Council [2017] NZEnvC 12. 8. Environmental Defence Society Inc v The New Zealand King Salmon Company Ltd [2014] NZSC 38. 9. Friends and Community of Ngawha Inc v Minister of Corrections [2002] NZRMA 401 (HC). 10. J F Investments Ltd v Queenstown Lakes District Council EnvC C48/06, 27 April 2006. 11. KPF Investments Ltd v Marlborough District Council [2014] NZEnvC 152. 12. Kuku Mara Partnership (Forsyth Bay) v Marlborough District Council EnvC W025/02, 16 July 2002. 13. Meridian Energy Limited v Central Otago District Council [2011] 1 NZLR 482 (HC). 14. Minhinnick v Minister of Corrections EnvC A043/2004, 6 April 2004. 15. New Zealand Rail v Marlborough District Council [1994] NZRMA 70 (HC). 16. New Zealand Transport Agency v Architectural Centre Inc [2015] NZHC 1991. 17. North Shore City Council v Auckland Regional Council [1997] NZRMA 59 (EnvC). 18. Pukekohe East Community Society Inc v Auckland Council [2017] NZEnvC 27. 19. Queenstown Airport Corporation Ltd v Queenstown Lakes District Council [2013] NZHC 2347. -

4899F Significant Natural Areas of Kaipara District Volume 1

SIGNIFICANT INDIGENOUS VEGETATION AND HABITATS OF KAIPARA DISTRICT, NORTHLAND – VOLUME 1 R4899f – Volume 1 SIGNIFICANT INDIGENOUS VEGETATION AND HABITATS OF KAIPARA DISTRICT, NORTHLAND – VOLUME 1 Contract Report No. 4899f April 2020 Project Team: Sarah Beadel - Project management Nick Goldwater – Project management, peer review Jarred Cusens, Matt Brown - Report author Federico Mazzieri – GIS Lynette Deacon - GIS Prepared for: Kaipara District Council Private Bag 1001 Dargaville 0340 99 SALA STREET, WHAKAREWAREWA, 3010, P.O. BOX 7137, TE NGAE, ROTORUA 3042 Ph 07-343-9017; Fax 07-343-9018, email [email protected], www.wildlands.co.nz CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 2. INTRODUCTION 2 3. METHODS 3 3.1 Review of significance criteria 3 3.2 Collation of existing information to update site information 3 3.3 Site assessments 4 3.4 GIS assessment and site mapping 4 3.5 Oblique aerial imagery 8 4. ECOLOGICAL CONTEXT – AN OVERVIEW 8 4.1 Overview 8 4.2 Land cover 8 4.3 Threatened land environments 9 4.4 Ecological districts of Kaipara District 10 5. INFORMATION ON EACH ECOLOGICAL DISTRICT 11 5.1 Overview 11 5.2 Kaipara Ecological District 11 5.2.1 Overview 11 5.2.2 Vegetation 12 5.3 Otamatea Ecological District 15 5.3.1 Overview 15 5.3.2 Vegetation 16 5.4 Rodney Ecological District (Northland) 19 5.4.1 Overview 19 5.4.2 Vegetation 20 5.5 Tangihua Ecological District 22 5.5.1 Overview 22 5.5.2 Vegetation 22 5.6 Tokatoka Ecological District 25 5.6.1 Overview 25 5.6.2 Vegetation 26 5.7 Tutamoe Ecological District 27 5.7.1 Overview 27 5.7.2 Vegetation 29 5.8 Waipū Ecological District 31 5.8.1 Overview 31 5.8.2 Vegetation 32 5.9 Whāngārei Ecological District 34 5.9.1 Overview 34 5.9.2 Vegetation 35 6. -

Government Announced Irg Projects 28 January 2021

GOVERNMENT ANNOUNCED IRG PROJECTS 28 JANUARY 2021 PROJECT FUNDED PROJECT NAME PROJECT OWNER SECTOR REGION VALUE $M AMOUNT $M Ferry Basin Redevelopment - Stage 1 Auckland Transport Transport Auckland $110.0 $50.0 Auckland City Mission HomeGround Auckland City Mission Social Auckland $110.0 $22.0 Northwestern Busway – early deliverables Auckland Transport/NZTA Transport Auckland $100.0 $50.0 1 Puhinui Interchange (Bus-Rail) Auckland Council/Auckland Transport Transport Auckland $69.0 $47.1 Te Whau Pathway Auckland Council Transport Auckland $37.3 $35.3 Te Mahurehure Expansion Projects Te Mahurehure Marae Community Auckland $19.0 $6.0 Kāinga Ora Mangere Priority Wastewater Upgrades Watercare Services Limited Housing Auckland $25.0 $25.0 Auckland Housing Programme: Tamaki stormwater and park upgrade bundle Auckland Council – Healthy Waters Housing Auckland $12.0 $11.3 Northcote Development Stormwater Trunk Provision Auckland Council – Healthy Waters Housing Auckland $14.3 $13.0 Auckland Housing Programme: Roskill South housing infrastructure bundle Auckland Council Housing Auckland $11.0 $10.0 Owairaka Development Stormwater Network Provision Auckland Council – Healthy Waters Housing Auckland $34.1 $31.2 Kainga Ora Mt Roskill Priority Water and Wastewater Upgrades Watercare Services Limited Housing Auckland $65.0 $65.0 Unitec Housing Development Marutūāhu Rōpū Housing Auckland $169.1 $75.0 Kainga Ora Tamaki priority Wastewater Upgrades Watercare Services Limited Housing Auckland $25.0 $25.0 Auckland Housing 3 Water Contingency Housing Auckland -

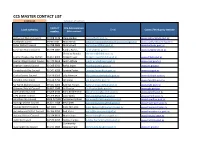

CCS MASTER CONTACT LIST 2/08/2021 1St Point of Contact

CCS MASTER CONTACT LIST 2/08/2021 1st point of contact Contact CCS Administrator Local authority Email Council/third party website number (Main contact) Ashburton District Council 03 308 5139 Clare Harden [email protected] www.ashburtondc.govt.nz Auckland Council 09 3010101 Mary Borok [email protected] www.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz Buller District Council 03 788 9683 Mira Schwill [email protected] www.bullerdc.govt.nz Carterton District Council 06 379 4081 Sandra Burles [email protected] www.cartertondc.co.nz Christine Renata [email protected] Central Hawkes Bay District 06 857 8060 Bridget Cover [email protected] www.chbdc.govt.nz Central Otago District Council 03 440 0618 Judith Whyte [email protected] www.codc.govt.nz Chatham Islands Council 03 305 0033 Barby Joyce [email protected] www.cic.govt.nz Christchurch City Council 03 941 6288 Lynette Foster [email protected] www.ccc.govt.nz Clutha District Council 03 419 0200 Lilly Paterson [email protected] www.cluthadc.govt.nz Dunedin City Council 03 474 3792 Jen Lucas [email protected] www.dunedin.govt.nz Far North District Council 09 401 5200 Kathryn Trewin [email protected] www.fndc.govt.nz Gisborne District Council 06 867 2049 Liz Proctor [email protected] www.gdc.govt.nz Gore District Council 03 209 0330 Karla Brotherston [email protected] www.goredc.govt.nz Grey District Council 03 769 8600 Leah Smith [email protected] www.greydc.govt.nz Hamilton City Council