Community Engagement on Climate Change Adaptation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Zealand Gazette

Jflumb. 66 1307 THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE WELLINGTON, THURSDAY, OCTOBER 25, 1945 Declaring a Portion of Railway Land near Brunner to be Crown Land Situated in Block V, Titirangi Survey District (Auckland R.D.). (S.O. 33701.) In the North Auckland Land District; as the same is more [L.8.] C. L. N. NEWALL, Governor-General particularly delineated on the plan marked P.W.D. 122415, deposited A PROCLAMATION in the office of the Minister of Works at Wellington, and thereon N pursuance and exercise of the powers and authorities vested coloured yellow. I in me by the Public Works Act, 1928, :ctnd of every other power and authority in anywise enabling me in this behalf, I, Cyril Given under the hand of His Excellency the Governor-General Louis Norton Newall, the Governor-General of the Dominion of of the Dominion of New Zealand, and issued under the Seal New Zealand, do hereby declare the land described in the Schedule of that Dominion, this 18th day of October, 1945. hereto to be Crown land subject to the Land Act, 1924. R. SE1v1PLE, Minister of Works. Gon sAVE THE KING ! SCHEDULE (P.vV. 34/3173/15.) ALL that parcel of land containing 1 acre, more or less, situate in the Borough of Brunner, being Lots 110, 111, 112, 113, on Deposited Plan No. 81, Town of Taylorville, and being all the land contained in Certificate of Title, Volume 12, folio 375 (Westland Registry) .. Land taken for Housing Purpose.<; i'.n the Borougli of JJ.fot·ueka In the vVestland Land District ; as the same is more particu larly delineated on the plan marked L.O. -

Part 2 | North Kaipara 2.0 | North Kaipara - Overview

Part 2 | North Kaipara 2.0 | North Kaipara - Overview | Mana Whenua by the accumulation of rainwater in depressions of sand. Underlying There are eight marae within the ironstone prevents the water from North Kaipara community area (refer leaking away. These are sensitive to the Cultural Landscapes map on environments where any pollution page 33 for location) that flows into them stays there. Pananawe Marae A significant ancient waka landing Te Roroa site is known to be located at Koutu. Matatina Marae Te Roroa To the east of the district, where Waikara Marae the Wairoa River runs nearby to Te Roroa Tangiteroria, is the ancient portage Waikaraka Marae route of Mangapai that connected Te Roroa the Kaipara with the lower reaches Tama Te Ua Ua Marae of the Whangārei Harbour. This Te Runanga o Ngāti Whātua portage extended from the Northern Ahikiwi Marae Wairoa River to Whangārei Harbour. Te Runanga o Ngāti Whātua From Tangiteroria, the track reached Taita Marae Maungakaramea and then to the Te Runanga o Ngāti Whātua canoe landing at the head of the Tirarau Marae Mangapai River. Samuel Marsden Ngāuhi; Te Runanga o Ngāti Whātua (1765-1838), who travelled over this route in 1820, mentions in his journal There are a number of maunga that Hongi Hika conveyed war and distinctive cultural landscapes canoes over the portage (see Elder, significant to Mana Whenua and the 1932). wider community within the North Kaipara areas. These include Maunga Mahi tahi (collaboration) of Te Ruapua, Hikurangi, and Tuamoe. opportunities for mana whenua, Waipoua, and the adjoining forests wider community and the council of Mataraua and Waima, make up to work together for the good of the largest remaining tract of native the northern Kaipara area are vast forests in Northland. -

Auckland Council, Far North District Council, Kaipara District Council and Whangarei District Council

Auckland Council, Far North District Council, Kaipara District Council and Whangarei District Council Draft Proposed Plan Change to the District / Unitary Plan Managing Risks Associated with Outdoor Use of Genetically Modified Organisms Draft Section 32 Report January 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Scope and Purpose of the Report 1 1.2 Development of the Plan Change 1 1.3 Structure of the Report 3 2. GENETICALLY MODIFIED ORGANISMS 4 2.1 Introduction 4 2.2 Benefits and Risks 5 2.2.1 Benefits 5 2.2.2 Risks 7 2.3 Risk Management and Precaution 10 2.4 Consultation 12 2.4.1 Community Concerns Regarding GMO Use 12 2.4.2 Māori Perspectives 14 2.4.3 Summary 15 2.5 Synopsis 16 3. THE PLAN CHANGE 17 3.1 Introduction 17 3.2 Significant Resource Management Issue 17 3.3 Objectives and Policies 18 3.4 Related Provisions 19 3.4.1 Activity Rules 19 3.4.2 General Development and Performance Standards 20 3.4.3 Definitions 20 4. SECTION 32 EVALUATION 21 4.1 Introduction 21 4.2 Alternative Means to Address the Issue 22 4.2.1 Do Nothing 22 4.2.2 Central Government Amendment to the HSNO Act 23 4.2.3 Local Authority Regulation through the RMA 24 4.2.4 Assessment of Alternatives Considered 24 4.3 Risk of Acting or Not Acting 26 4.3.1 Ability to Deliver a Precautionary Approach 27 4.3.2 Proportionate Action and Difficulties Arising From Inaction 29 i 4.4 Appropriateness of the Objectives in Achieving the Purpose of the Act 31 4.5 Appropriateness, Costs and Benefits of Policies, Rules and Other Methods 33 4.5.1 Appropriateness 33 4.5.2 Costs 34 4.5.3 Benefits 36 5. -

Ban Single Use Plastic Bags Petition.Pdf

11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 Recipient: Kaipara District Council, Mayor and Councillors of Kaipara District Council Letter: Greetings, Ban Single-use Plastic Bags in Kaipara 39 Signatures Name Location Date Margaret Baker New Zealand 2017-07-01 Mike Hooton Paparoa, New Zealand 2017-07-01 Lyn Little northland, New Zealand 2017-07-01 Wendy Charles Maungaturoto, New Zealand 2017-07-01 Stuart W J Brown Maungaturoto, New Zealand 2017-07-01 Lisa Cotterill Dargaville, New Zealand 2017-07-01 Elsie-May Dowling Auckland, New Zealand 2017-07-01 Nick Rountree Maungaturoto, New Zealand 2017-07-01 dido dunlop auckland, New Zealand 2017-07-01 Wayne David Millar Paparoa , Kaipara , Northland, New 2017-07-01 Zealand Eve-Marie Allen Northland, New Zealand 2017-07-01 Grant George Maungaturoto, New Zealand 2017-07-01 Lisa Talbot Kaiwaka, New Zealand 2017-07-01 Jana Campbell Auckland, New Zealand 2017-07-01 Sarah Clements Auckland, New Zealand 2017-07-01 Gail Aiken Rawene, New Zealand 2017-07-01 Elizabeth Clark Maungaturoto, Alabama, US 2017-07-01 Helen Curreen Mangawhai, New Zealand 2017-07-01 Asta Wistrand Kaitaia, New Zealand 2017-07-01 Rosanna Donovan dargaville, New Zealand 2017-07-01 40 Name Location Date Wes Watson Kaikohe, New Zealand 2017-07-01 Nat V East Brisbane, Australia 2017-07-01 Jordan Rakoia Kaipara, New Zealand 2017-07-01 CAREN Davis Mangawhai Heads, New Zealand 2017-07-02 Michelle Casey Auckland, New Zealand 2017-07-02 Anna Kingi Mangawhai, New Zealand 2017-07-02 Misty Lang Auckland, -

Exposure to Coastal Flooding

Coastal Flooding Exposure Under Future Sea-level Rise for New Zealand Prepared for The Deep South Challenge Prepared by: Ryan Paulik Scott Stephens Sanjay Wadhwa Rob Bell Ben Popovich Ben Robinson For any information regarding this report please contact: Ryan Paulik Hazard Analyst Meteorology and Remote Sensing +64-4-386 0601 [email protected] National Institute of Water & Atmospheric Research Ltd Private Bag 14901 Kilbirnie Wellington 6241 Phone +64 4 386 0300 NIWA CLIENT REPORT No: 2019119WN Report date: March 2019 NIWA Project: DEPSI18301 Quality Assurance Statement Reviewed by: Dr Michael Allis Formatting checked by: Patricia Rangel Approved for release by: Dr Andrew Laing © All rights reserved. This publication may not be reproduced or copied in any form without the permission of the copyright owner(s). Such permission is only to be given in accordance with the terms of the client’s contract with NIWA. This copyright extends to all forms of copying and any storage of material in any kind of information retrieval system. Whilst NIWA has used all reasonable endeavours to ensure that the information contained in this document is accurate, NIWA does not give any express or implied warranty as to the completeness of the information contained herein, or that it will be suitable for any purpose(s) other than those specifically contemplated during the Project or agreed by NIWA and the Client. Contents Executive summary ............................................................................................................. 6 1 Context for estimating coastal flooding exposure with rising seas ............................. 14 1.1 Coastal flooding processes in a changing climate .................................................. 14 1.2 National and regional coastal flooding exposure .................................................. -

Before the Environment Court Between

BEFORE THE ENVIRONMENT COURT Decision No. [2014] NZEnvC 182 IN THE MATTER of an appeal under Clause 14 of Schedule 1 of the Resource Management Act 1991 (the Act) concerning Variation 1 to the Kaipara District Plan, and an appeal under Section 120 of the Act BETWEEN CCALVELEY (ENV-2012-AKL-000138) Appellant MANGAWHAI HEADS HOLDINGS LIMITED (ENV-2013-AKL-000012) Appellant AND KAIP ARA DISTRICT COUNCIL Respondent Hearing: at Aucldand 5-9 and 29-30 May 2014 Court: Enviromnent Judge J J M Hassan Environment Cmmnissioner R M Dunlop Deputy Environment Commissioner J Illingswmth Appearances: Mr A Webb for C Calveley and Mangawhai Heads Holdings Limited Mr M Allan for the Kaipara District Council Mr M Savage for Catherine Hawley, Jolm Hawley, Mangawhai Ratepayers and Residents Association, Marunui Conservation Limited, The Friends of the Brynclmwyns Society Incorporated (section 274 patties) Date of Decision: 27 August 2014 27 August 2014 2 DECISION OF THE ENVIRONMENT COURT The MHHL appeal A: For the reasons set out: (a) The appeal is disallowed in part and the Council's decisions are confitmed to the extent that: (i) Land use consent to establish seven houses on Lot 1 DP 316176 is refused; (ii) The appellant's application for lots 15 and 17 to 20 to be included as pmi of the subdivision of Lots I and 2 DP 316176 is refi.lsed; (b) To allow for the inclusion in the subdivision consent for the subdivision of Lots 1 m1d 2 DP 316176 of conditions that give effect to this decision, we direct tbe Council to confer with the appellant and section 27 -

Environmental Scan

Kaipara District Council Environmental Scan August 2013 Intentional Blank 2127.02 / 2013-2014 KD Environmental Scan 2013 V2 A. Executive Summary This Environmental Scan was completed in July 2013. At the time of compiling this information, results of the 2013 Census were not yet available so a large amount of information and analysis is unavailable or deemed to be out of date. It is hoped that information from the 2013 Census will be available for inclusion in the next issue of the Environmental Scan. The purpose of this document is to provide a quick overview of the legal, social, economic, physical and technical environment in which the Council operates. This second issue of the environmental scan is to be followed by later editions which will ensure up to date information on key indicators is always available. The key findings which are highlighted within this Environmental Scan are: Legal Central government is presently reforming the local government sector. The next round of reforms will focus on Councils’ regulatory functions; The Local Government Commission is currently considering reorganisation of local government across the whole of Northland. This may involve amalgamation of Kaipara into one or more of the other local authorities; Auckland Council is developing its Unitary Plan. The Draft Unitary Plan allows for much greater intensification of Auckland and will create more intensified housing around transport and shopping nodes. Central Government is questioning this approach, suggesting that the plan allow more greenfield developments (urban sprawl). The availability and nature of housing in Auckland will have flow on effects for Kaipara. Social Most of the District’s towns have declining or stable school rolls. -

Notes Subscription Agreement)

Amendment and Restatement Deed (Notes Subscription Agreement) PARTIES New Zealand Local Government Funding Agency Limited Issuer The Local Authorities listed in Schedule 1 Subscribers 3815658 v5 DEED dated 2020 PARTIES New Zealand Local Government Funding Agency Limited ("Issuer") The Local Authorities listed in Schedule 1 ("Subscribers" and each a "Subscriber") INTRODUCTION The parties wish to amend and restate the Notes Subscription Agreement as set out in this deed. COVENANTS 1. INTERPRETATION 1.1 Definitions: In this deed: "Notes Subscription Agreement" means the notes subscription agreement dated 7 December 2011 (as amended and restated on 4 June 2015) between the Issuer and the Subscribers. "Effective Date" means the date notified by the Issuer as the Effective Date in accordance with clause 2.1. 1.2 Notes Subscription Agreement definitions: Words and expressions defined in the Notes Subscription Agreement (as amended by this deed) have, except to the extent the context requires otherwise, the same meaning in this deed. 1.3 Miscellaneous: (a) Headings are inserted for convenience only and do not affect interpretation of this deed. (b) References to a person include that person's successors, permitted assigns, executors and administrators (as applicable). (c) Unless the context otherwise requires, the singular includes the plural and vice versa and words denoting individuals include other persons and vice versa. (d) A reference to any legislation includes any statutory regulations, rules, orders or instruments made or issued pursuant to that legislation and any amendment to, re- enactment of, or replacement of, that legislation. (e) A reference to any document includes reference to that document as amended, modified, novated, supplemented, varied or replaced from time to time. -

QUARTERLY INFRASTRUCTURE REFERENCE GROUP UPDATE Q1: to 31 MARCH 2021 QUARTERLY IRG UPDATE 2 Q1: to 31 MARCH 2021

Building Together • Hanga Ngātahi QUARTERLY INFRASTRUCTURE REFERENCE GROUP UPDATE Q1: to 31 MARCH 2021 QUARTERLY IRG UPDATE 2 Q1: to 31 MARCH 2021 IRG PROGRAMME OVERVIEW .....................................3 PROGRESS TO DATE ................................................4 COMPLETED PROJECTS THIS QUARTER ...........................5 REGIONAL SUMMARY .............................................6 UPDATE BY REGION NORTHLAND ........................................................8 AUCKLAND .........................................................9 WAIKATO ...........................................................10 BAY OF PLENTY ....................................................11 GISBORNE ..........................................................12 HAWKE’S BAY ......................................................13 TARANAKI ..........................................................14 CONTENTS MANAWATŪ-WHANGANUI ........................................15 WELLINGTON .......................................................16 TOP OF THE SOUTH ................................................17 WEST COAST .......................................................18 CANTERBURY .......................................................19 OTAGO ..............................................................20 SOUTHLAND ........................................................21 NATIONWIDE .......................................................22 FULL PROJECT LIST ................................................23 GLOSSARY ..........................................................31 -

Population Projections 2018-2051 Kaipara District Council

Population Projections 2018-2051 Kaipara District Council October 2020 Authorship This report has been prepared by Nick Brunsdon Email: [email protected] All work and services rendered are at the request of, and for the purposes of the client only. Neither Infometrics nor any of its employees accepts any responsibility on any grounds whatsoever, including negligence, to any other person or organisation. While every effort is made by Infometrics to ensure that the information, opinions, and forecasts are accurate and reliable, Infometrics shall not be liable for any adverse consequences of the client’s decisions made in reliance of any report provided by Infometrics, nor shall Infometrics be held to have given or implied any warranty as to whether any report provided by Infometrics will assist in the performance of the client’s functions. 3 Kaipara Population Projections – October 2020 Table of Contents Executive summary ........................................................................ 4 Introduction ......................................................................................5 Our Approach ..................................................................................6 Employment ................................................................................................................................. 6 Migration .......................................................................................................................................7 Existing Population .................................................................................................................... -

HRE05002-038.Pdf(PDF, 152

Appendix S: Parties Notified List of tables Table S1: Government departments and Crown agencies notified ........................... 837 Table S2: Interested parties notified .......................................................................... 840 Table S3: Interested Māori parties ............................................................................ 847 Table S1: Government departments and Crown agencies notified Job Title Organisation City Manager Biosecurity Greater Wellington - The Regional Council Masterton 5915 Environment Health Officer Wairoa District Council Wairoa 4192 Ministry of Research, Science & Wellington 6015 Technology (MoRST) Manager, Animal Containment AgResearch Limited Hamilton 2001 Facility Group Manager, Legal AgResearch Limited Hamilton Policy Analyst Human Rights Commission Auckland 1036 Management, Monitoring & Ministry of Pacific Island Affairs Wellington 6015 Governance Fish & Game Council of New Zealand Wellington 6032 Engineer Land Transport Safety Authority Wellington 6015 Senior Fisheries Officer Fish & Game Eastern Region Rotorua 3220 Adviser Ministry of Research, Science & Wellington 6015 Technology (MoRST) Programme Manager Environment Waikato Hamilton 2032 Biosecurity Manager Environment Southland Invercargill 9520 Dean of Science and University of Waikato Hamilton 3240 Technology Director National Institute of Water & Atmospheric Wellington 6041 Research Limited (NIWA) Chief Executive Officer Horticulture and Food Research Institute Auckland 1020 (HortResearch Auckland) Team Leader Regulatory -

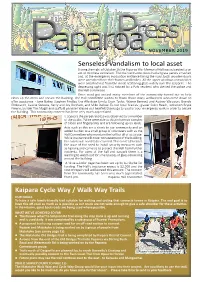

Senseless Vandalism to Local Asset Kaipara Cycle Way / Walk Way Trails

NOVEMBER 2019 Senseless vandalism to local asset During the night of October 26 the Paparoa War Memorial Hall was subjected to an act of mindless vandalism. The main entrance doors had all glass panels smashed and, at the emergency evacuation entrance facing the road, both wooden doors were wrenched from their frames and broken. All the upper windows on two sides were smashed out from the inside scattering glass widely over the carparks. The depressing sight was first noticed by a Pahi resident who alerted the police and the Hall committee. Once word got around many members of the community turned out to help clean up the mess and secure the building. The Hall Committee wishes to thank those many wellwishers who came down to offer assistance - Jane Bailey, Stephen Findlay, the Allardyce family, Dyan Taylor, Wayne Bennett and Audrey Waipouri, Brenda Elmbranch, Lawrie Stevens, Kerry and Joy Bonham, and Mike Dallow. To our local 'tradies', glazier Colin Heath, locksmith Bryce Frewin, builder Tim Magill and scaffold provider Wayne our hearfelt thanks go to you for your emergency work in order to secure the building. This community concern has been very much appreciated. It appears the perpetrator(s) was observed by a member of the public. Police were able to obtain forensic samples of blood and fingerprints and are following up on leads. Acts such as this are a shock to our community and an added burden to a small group of volunteers such as the Hall Committee who maintain the hall for all of us to use. While insurance will cover reinstatement of the building, the excess will need to be covered.