Seabird Monitoring Instruction Manual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Darwin Initiative for the Survival of Species Annual Report

Darwin Initiative for the Survival of Species Annual Report 1. Darwin Project Information Project title Establishment of Penguin Monitoring Programme Country(ies) Chile Contractor Environmental Research Unit Project Reference No. 162/9/007 Grant Value £10,350 p.a. for 3 years Start/Finishing dates April 2001 to March 2004 Reporting period April 2003 2. Project Background • Briefly describe the location and circumstances of the project and the problem that the project aims to tackle. The project takes place on Magdalena Island, near the city of Punta Arenas in southern Chile. Magdalena Island is one of Chile’s most important breeding sites for Magellanic penguins, a species whose global distribution is restricted to southern South America. Best guess estimates put the current world population of Magellanic penguins at around 1.5 million breeding pairs, with approximately 700,000 pairs in Chile, 650,000 pairs in Argentina and 150,000 pairs in the Falkland Islands (Bingham 1998, Bingham & Mejias 1999, Gandini et al. 1998). Population studies in the Falkland Islands conducted by Mike Bingham have revealed an 80% decline in Magellanic penguins between 1990/91 and 2002/03. A reduction of fish and squid resulting from large-scale commercial fishing appears to be the cause of the penguin decline, through reduction of foraging rates, breeding success and juvenile survival (Bingham 2002). Population studies conducted in Argentina show evidence of decline at some colonies, but not all (Boersma 1997). Declines in Argentina appear to be largely the result of high adult and juvenile mortality caused by oil pollution. An estimated 40,000 Magellanic penguins are killed by oil pollution every year along the coast of Argentina, representing the main cause of adult mortality (Gandini et al. -

Wild Patagonia & Central Chile

WILD PATAGONIA & CENTRAL CHILE: PUMAS, PENGUINS, CONDORS & MORE! NOVEMBER 1–18, 2019 Pumas simply rock! This year we enjoyed 9 different cats! Observing the antics of lovely Amber here and her impressive family of four cubs was certainly the highlight in Torres del Paine National Park — Photo: Andrew Whittaker LEADERS: ANDREW WHITTAKER & FERNANDO DIAZ LIST COMPILED BY: ANDREW WHITTAKER VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM Sensational, phenomenal, outstanding Chile—no superlatives can ever adequately describe the amazing wildlife spectacles we enjoyed on this year’s tour to this breathtaking and friendly country! Stupendous world-class scenery abounded with a non-stop array of exciting and easy birding, fantastic endemics, and super mega Patagonian specialties. Also, as I promised from day one, everyone fell in love with Chile’s incredible array of large and colorful tapaculos; we enjoyed stellar views of all of the country’s 8 known species. Always enigmatic and confiding, the cute Chucao Tapaculo is in the Top 5 — Photo: Andrew Whittaker However, the icing on the cake of our tour was not birds but our simply amazing Puma encounters. Yet again we had another series of truly fabulous moments, even beating our previous record of 8 Pumas on the last day when I encountered a further 2 young Pumas on our way out of the park, making it an incredible 9 different Pumas! Our Puma sightings take some beating, as they have stood for the last three years at 6, 7, and 8. For sure none of us will ever forget the magical 45 minutes spent observing Amber meeting up with her four 1- year-old cubs as they joyfully greeted her return. -

Birds of Chile a Photo Guide

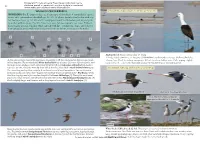

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be 88 distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical 89 means without prior written permission of the publisher. WALKING WATERBIRDS unmistakable, elegant wader; no similar species in Chile SHOREBIRDS For ID purposes there are 3 basic types of shorebirds: 6 ‘unmistakable’ species (avocet, stilt, oystercatchers, sheathbill; pp. 89–91); 13 plovers (mainly visual feeders with stop- start feeding actions; pp. 92–98); and 22 sandpipers (mainly tactile feeders, probing and pick- ing as they walk along; pp. 99–109). Most favor open habitats, typically near water. Different species readily associate together, which can help with ID—compare size, shape, and behavior of an unfamiliar species with other species you know (see below); voice can also be useful. 2 1 5 3 3 3 4 4 7 6 6 Andean Avocet Recurvirostra andina 45–48cm N Andes. Fairly common s. to Atacama (3700–4600m); rarely wanders to coast. Shallow saline lakes, At first glance, these shorebirds might seem impossible to ID, but it helps when different species as- adjacent bogs. Feeds by wading, sweeping its bill side to side in shallow water. Calls: ringing, slightly sociate together. The unmistakable White-backed Stilt left of center (1) is one reference point, and nasal wiek wiek…, and wehk. Ages/sexes similar, but female bill more strongly recurved. the large brown sandpiper with a decurved bill at far left is a Hudsonian Whimbrel (2), another reference for size. Thus, the 4 stocky, short-billed, standing shorebirds = Black-bellied Plovers (3). -

A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences 2010 The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World" (2010). Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard. 20. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans/20 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 200 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World Paul A. Johnsgard Pages xvii–xxiii: recent taxonomic changes, I have revised sev- Introduction to the Family Anatidae eral of the range maps to conform with more current information. For these updates I have Since the 978 publication of my Ducks, Geese relied largely on Kear (2005). and Swans of the World hundreds if not thou- Other important waterfowl books published sands of publications on the Anatidae have since 978 and covering the entire waterfowl appeared, making a comprehensive literature family include an identification guide to the supplement and text updating impossible. -

Bleaker Island Settlement & the South

Distance: 1.5 - 2 km Time: 30-45 min Terrain: Moderate 1 SETTLEMENT TRAIL 89 Semaphore Hill This short trail is ideal for families and provides a great introduction to the immediate area. Taking in whale bones, settlement buildings and gardens, the walk also provides a glimpse into farming life with the chance to watch farm activities such as shearing or cattle work if the time is right. It includes a short climb to the Shearing shed summit of Bleaker’s highest hill, an altitude of just 27m (89 feet), giving views across the island and surrounding ocean. 1 Main route Settlement Walk first to the BBQ hut in front of Cassard House. BBQ hut Take time to admire the “Essence of our Community” Imperial artwork on the south-facing wall then go through the gate cormorants Long to see a full Sei whale skeleton, above the beach, nestled 0 100 200 300 400 500 Gulch into the green. 2 Meters From here a route can usually be picked out along the Rockhopper shore in a northerly direction towards the shearing shed Short Gulch penguins and stock yards, taking in a pretty little bay with a variety First Is. of birds. If the weather is very wet and the shoreline muddy, Pebbly Bay an alternative is to walk back through the gate by the Tips: bar-b-que hut, down through the low valley via the wind Ask if anything is happening on the farm, to turbine and solar panels, then through two time the walk accordingly, but remember to gates along a clear track. -

Pluvianellus Socialis NOMBRE COMÚN: Chorlo De Magallanes

FICHA DE ANTECEDENTES DE ESPECIE Id especie: NOMBRE CIENTÍFICO: Pluvianellus socialis NOMBRE COMÚN: chorlo de Magallanes Pareja de chorlo de Magallanes (Pluvianellus socialis) en Laguna Los Palos, un ambiente de laguna salobre típico donde nidifica la especie. Uno de los tres sitios donde se ha confirmado su reproducción en Chile. Fotografía: Pablo Gutiérrez Maier. 22 de octubre de 2017 (puede sea utilizada en la página Web del sistema de clasificación de especies y del inventario nacional de especies) Taxonomía (nombre en latín de las categorías taxonómicas a las que pertenece esta especie) Reino: Animalia Orden: Charadriiformes Phyllum/División: Chordata Familia: Pluvianellidae Clase: Aves Género: Pluvianellus Sinonimia (otros nombres científicos que la especie ha tenido, pero actualmente ya no se usan) - Antecedentes Generales (breve descripción de los ejemplares, incluida características físicas, reproductivas u otras características relevantes de su historia natural. Se debería incluir también aspectos taxonómicos, en especial la existencia de subespecies o variedades. Recuerde poner las citas bibliográficas) Monotípica. Ave de 19-21 cm de largo. Adultos poseen un plumaje color gris en el dorso, pecho y cabeza. El abdomen es blanquecino en su totalidad. El pico es corto y de color negro (Jaramillo 2004). Las patas son cortas y rosáceas, el iris es rojizo. Sin dimorfismo sexual. Juveniles con dorso grisáceo moteado, patas amarillentas y el ojo es de un rojo menos intenso (del Hoyo et al. 2018). El nido se ubica a una distancia variable desde la orilla de la laguna (70 cm a 25 m), el cual consiste en una depresión donde se agrupan pequeñas piedras sin materiales aislantes (Jehl 1975). -

Patagonia Wildlife Safari Paul Prior BIRD SPECIES - Total 177 Seen/ No

BIRD CHECKLIST Leaders: Steve Ogle Eagle-Eye Tours 2018 Patagonia Wildlife Safari Paul Prior BIRD SPECIES - Total 177 Seen/ No. Common Name Latin Name Heard RHEIFORMES: Rheidae 1 Lesser Rhea Rhea pennata s TINAMIFORMES: Tinamidae 2 Elegant Crested-Tinamou Eudromia elegans s ANSERIFORMES: Anhimidae 3 Southern Screamer Chauna torquata s ANSERIFORMES: Anatidae 4 White-faced Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna viduata s 5 Fulvous Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna bicolor s 6 Black-necked Swan Cygnus melancoryphus s 7 Coscoroba Swan Coscoroba coscoroba s 8 Upland Goose Chloephaga picta s 9 Kelp Goose Chloephaga hybrida s 10 Flying Steamer-Duck Tachyeres patachonicus s 11 Flightless Steamer-Duck Tachyeres pteneres s 12 White-headed Steamer-Duck Tachyeres leucocephalus s 13 Crested Duck Lophonetta specularioides s 14 Spectacled Duck Speculanas specularis s 15 Brazilian Teal Amazonetta brasiliensis s 16 Torrent Duck Merganetta armata s 17 Chiloe Wigeon Anas sibilatrix s 18 Cinnamon Teal Anas cyanoptera s 19 Red Shoveler Anas platalea s 20 Yellow-billed Pintail Anas georgica s 21 Silver Teal Anas versicolor s 22 Yellow-billed Teal Anas flavirostris s 23 Rosy-billed Pochard Netta peposaca s 24 Black-headed Duck Heteronetta atricapilla s 25 Lake Duck Oxyura vittata s PODICIPEDIFORMES: Podicipedidae 26 White-tufted Grebe Rollandia rolland s 27 Great Grebe Podiceps major s 28 Silvery Grebe Podiceps occipitalis s PHOENICOPTERIFORMES: Phoenicopteridae 29 Chilean Flamingo Phoenicopterus chilensis s SPHENISCIFORMES: Spheniscidae 30 King Penguin Aptenodytes patagonicus s 31 Gentoo Penguin Pygoscelis papua s 32 Magellanic Penguin Spheniscus magellanicus s PROCELLARIIFORMES: Diomedeidae 33 Black-browed Albatross Thalassarche melanophris s Page 1 of 6 BIRD CHECKLIST Leaders: Steve Ogle Eagle-Eye Tours 2018 Patagonia Wildlife Safari Paul Prior BIRD SPECIES - Total 177 Seen/ No. -

Learning About BUSH Stone-Curlews

© 2018 Nature Conservation Working Group. This publication has been prepared as a resource for schools. Schools may copy, distribute and otherwise freely deal with this publication, or any part of it, for any educational purpose, provided that Nature Conservation Working Group is attributed as the owner. Acknowledgements: Jan Lubke and Judy Frankenberg from the Nature Conservation Working Group, Elisa Tack from Murray Local Land Services, Owen Dunlop from Petaurus Education Group Inc. and Val White. This resource was funded by Nature Conservation Working Group and supported by Murray Local Land Services through funding from NSW Catchment Action. Author: Peter Coleman, PeeKdesigns Photographers: Jan Lubke, Chris Tzaros (front cover), Raoul Slater, Simon Dallinger, Kelly Coleman, Thomas Brown, Darren Marshall Design: PeeKdesigns www.peekdesigns.com.au Printed on 100% recycled and uncoated stock. by Peter Coleman LeARnInG ABOUt BUSH StOne-CURLeWS CONTENTS Introduction for teachers ........................................................2 What are Bush Stone-curlews? ...................................................6 Activity: Colouring the Curlew . 7 Weir-loo ....................................................................9 Activity: Did you hear that? . 10 Activity: Grouping similar things . 11 Classification ................................................................12 Activity: Find the key to the name . 13 Activity: Making an Origami Curl . 14 Habitat ....................................................................16 Activity: -

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does Not Include Alcidae

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does not include Alcidae CREATED BY AZA CHARADRIIFORMES TAXON ADVISORY GROUP IN ASSOCIATION WITH AZA ANIMAL WELFARE COMMITTEE Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Published by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums in association with the AZA Animal Welfare Committee Formal Citation: AZA Charadriiformes Taxon Advisory Group. (2014). Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual. Silver Spring, MD: Association of Zoos and Aquariums. Original Completion Date: October 2013 Authors and Significant Contributors: Aimee Greenebaum: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Vice Chair, Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Alex Waier: Milwaukee County Zoo, USA Carol Hendrickson: Birmingham Zoo, USA Cindy Pinger: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Chair, Birmingham Zoo, USA CJ McCarty: Oregon Coast Aquarium, USA Heidi Cline: Alaska SeaLife Center, USA Jamie Ries: Central Park Zoo, USA Joe Barkowski: Sedgwick County Zoo, USA Kim Wanders: Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Mary Carlson: Charadriiformes Program Advisor, Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Perry: Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Crook-Martin: Buttonwood Park Zoo, USA Shana R. Lavin, Ph.D.,Wildlife Nutrition Fellow University of Florida, Dept. of Animal Sciences , Walt Disney World Animal Programs Dr. Stephanie McCain: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Veterinarian Advisor, DVM, Birmingham Zoo, USA Phil King: Assiniboine Park Zoo, Canada Reviewers: Dr. Mike Murray (Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA) John C. Anderson (Seattle Aquarium volunteer) Kristina Neuman (Point Blue Conservation Science) Sarah Saunders (Conservation Biology Graduate Program,University of Minnesota) AZA Staff Editors: Maya Seaman, MS, Animal Care Manual Editing Consultant Candice Dorsey, PhD, Director of Animal Programs Debborah Luke, PhD, Vice President, Conservation & Science Cover Photo Credits: Jeff Pribble Disclaimer: This manual presents a compilation of knowledge provided by recognized animal experts based on the current science, practice, and technology of animal management. -

Attempting to See One Member of Each of the World's Bird Families Has

Attempting to see one member of each of the world’s bird families has become an increasingly popular pursuit among birders. Given that we share that aim, the two of us got together and designed what we believe is the most efficient strategy to pursue this goal. Editor’s note: Generally, the scientific names for families (e.g., Vireonidae) are capital- ized, while the English names for families (e.g., vireos) are not. In this article, however, the English names of families are capitalized for ease of recognition. The ampersand (&) is used only within the name of a family (e.g., Guans, Chachalacas, & Curassows). 8 Birder’s Guide to Listing & Taxonomy | October 2016 Sam Keith Woods Ecuador Quito, [email protected] Barnes Hualien, Taiwan [email protected] here are 234 extant bird families recognized by the eBird/ Clements checklist (2015, version 2015), which is the offi- T cial taxonomy for world lists submitted to ABA’s Listing Cen- tral. The other major taxonomic authority, the IOC World Bird List (version 5.1, 2015), lists 238 families (for differences, see Appendix 1 in the expanded online edition). While these totals may appear daunting, increasing numbers of birders are managing to see them all. In reality, save for the considerable time and money required, finding a single member of each family is mostly straightforward. In general, where family totals or family names are mentioned below, we use the eBird/Clements taxonomy unless otherwise stated. Family Feuds: How do world regions compare? In descending order, the number of bird families supported by con- tinental region are: Asia (125 Clements/124 IOC), Africa (122 Clem- ents/126 IOC), Australasia (110 Clements/112 IOC), North America (103 Clements/IOC), South America (93 Clements/94 IOC), Europe (73 Clements/74 IOC ), and Antarctica (7 Clements/IOC). -

UK-First-Breeding-Register.Pdf

INTRODUCTION TO EDITION The original author and compiler of this record, Dave Coles has devoted a great deal of his time in creating a unique reference document which I am privileged to continue working with. By its very nature the document in a living project which will continue to grow and evolve and I can only hope and wish that I have the dedication as Dave has had in ensuring the continuity of the “First Breeding Register”. Initially all my additions and edits will be indicated in italics though this will not be used in the main body of the record (when a new record is added). Simon Matthews (2011) It is over eighty years since Emilius Hopkinson collated his RECORDS OF BIRDS BRED IN CAPTIVITY, which formed the starting point for my attempt at recording first breeding records for the UK. Since the first edition of my records was published in 1986, classification has changed several times and the present edition incorporates this up-dated classification as well as first breeding recorded since then. The research needed to produce the original volume took many years to complete and covered most avicultural literature. Since that time numerous people have kept me abreast of further breedings and pointing out those that have slipped the net. This has hopefully enabled the records to be kept up-to- date. To those I would express my thanks as indeed I do to all that have cast their eyes over the new list and passed comments, especially the ever helpful Reuben Girling who continues to pass on enquiries. -

Standards for Monitoring Nonbreeding Shorebirds in the Western Hemisphere

Standards for Monitoring Nonbreeding Shorebirds in the Western Hemisphere Program for Regional and International Shorebird Monitoring (PRISM) October 2018 Mike Ausman Citation: Program for Regional and International Shorebird Monitoring (PRISM). 2018. Standards for Monitoring Nonbreeding Shorebirds in the Western Hemisphere. Unpublished report, Program for Regional and International Shorebird Monitoring (PRISM). Available at: https://www.shorebirdplan.org/science/program-for-regional-and- international-shorebird-monitoring/. Primary Authors: Matt Reiter, Chair, PRISM, Point Blue Conservation Science, [email protected]; and Brad A. Andres, National Coordinator U.S. Shorebird Conservation Partnership, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, [email protected]. Acknowledgements Both current and previous members of the PRISM Committee, workshop attendees in Panama City and Colorado, and additional reviewers made this document possible: Asociación Calidris – Diana Eusse, Carlos Ruiz Birdlife International – Isadora Angarita BirdsCaribbean – Lisa Sorensen California Department of Fish and Wildlife – Lara Sparks Environment and Climate Change Canada, Canadian Wildlife Service – Mark Drever, Christian Friis, Ann McKellar, Julie Paquet, Cynthia Pekarik, Adam Smith; Environment and Climate Change Canada, Science and Technology – Paul Smith Centro de Ornitologia y Biodiversidad (CORBIDI) – Fernando Angulo El Centro de Investigación Científica y de Educación Superior de Ensenada – Eduardo Palacios Fundación Humedales – Daniel Blanco Manomet – Stephen Brown, Rob Clay, Arne Lesterhuis, Brad Winn Museo Nacional de Costa Rica – Ghisselle Alvarado National Audubon Society – Melanie Driscoll, Matt Jeffery, Maki Tazawa Point Blue Conservation Science – Catherine Hickey, Matt Reiter Quetzalli – Salvadora Morales, Orlando Jarquin Red de Observadores de Aves y Vida Silvestre de Chile (ROC) – Heraldo Norambuena SalvaNatura – Alvaro Moises SAVE Brasil – Juliana Bosi Almeida Simon Fraser University – Richard Johnston Sociedad Audubon de Panamá – Karl Kaufman, Rosabel Miró U.S.