Dissertation Van Straaten

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

January, 2017 Raga Koushikranjani (Kaishikranjani,Chandrahas,Bahaderkouns, Chandramukhitypeii) in This Month We Shall Study Raga Koushikranjani

Raga of the Month- January, 2017 Raga Koushikranjani (Kaishikranjani,Chandrahas,BahaderKouns, ChandramukhiTypeII) In this month we shall study Raga Koushikranjani. This raga was introduced by Late Pandit Chidanand Nagarkar*. The Raga is based on the platform of Raga Chandrakouns. Shuddha Rishabh is introduced in Arohi as well as Avarohi order and Pancham is varjya swara. The Scale of the Raga Koushikranjani is SRgMdN. The Raga is included in Asavari Thata and in Melakartha No. 21 Kirwani in Carnatic Music. Raga Nadasanjivi of Carnatic Music resembles Raga Koushikranjini closely. Although Chandrakouns effect is prominent in this raga, phrases SRg-Rs and SRgM (without stress or elongation of Komal Gandhar) hints Raga Abhogi. Phrase SRM, which is a characteristic phrase of Raga Chandraprabha, is avoided. Aroha: SRgMdNS’’; Avaroha: S’’ NdMgRS; Vadi - Madhyama; Samvadi- Shadja; Chalan- S, ‘N’d, ‘N, S; ‘g’M’d’NS; ‘NSR ‘NS‘d, ‘N-S; SRgRS, SRgM, gRgM, gMd, MgR, RgMS, ‘d’NS; gMdN, N, MdMN, dNS’’, NS’’ d-M, gRgM, gRS; SRgM, gMd, MdN, dNS’’, S’’R’’g’’M’’R’’S’’, NS’’R’’ NS’’ d, MgMd, MgR- gMRS. The Raga is documented in the book Abhinav Raga Darpan by Pandit K B Kunte and (as Raga Chandrahas) in Volume II of Raga-Darshana by Pandit Manikbua Thakurdas. (Raga Nadasanjivi- Ref. RagaPravaham-by Dr. M N Dhandapani and D Pattamal) * CHIDANAND DATTATREY NAGARKAR, was born in 1919 in Bangalore. Chidanand inherited all his musical talents from his father, who had a flair for singing Bhajans and stage acting (including Natya Sangeet). Chidanand received rigorous training under Acharya Pandit S.N.Ratanjankar and Ustad Agha Samshuddin Hyder for six years. -

Anoushka Shankar Thursday, May 2, 2019 at 8:00Pm This Is the 939Th Concert in Koerner Hall

Anoushka Shankar Thursday, May 2, 2019 at 8:00pm This is the 939th concert in Koerner Hall Anoushka Shankar, sitar Ojas Adhiya, tabla Pirashanna Thevarajah, mridangam Ravichandra Kulur, flute Danny Keane, cello & piano Kenji Ota, tanpura Anoushka Shankar Sitar player and composer Anoushka Shankar is a singular figure in the Indian classical and progressive world music scenes. Her dynamic and spiritual musicality has garnered several prestigious accolades, including six Grammy Award nominations, recognition as the youngest – and first female – recipient of a British House of Commons Shield, credit as an Asian Hero by TIME magazine, an Eastern Eye Award for Music, and a Songlines Best Artist Award. Most recently, she became one of the first five female composers to have been added to the UK A-level music syllabus. Deeply rooted in the Indian classical music tradition, Shankar studied exclusively from the age of nine under her father and guru, the late Ravi Shankar, and made her professional debut as a classical sitarist at the age of 13. By the age of 20, she had made three classical recordings for EMI/Angel and received her first Grammy nomination, thereby becoming the first Indian female and youngest-ever nominee in the world music category. She is also the first Indian artist to perform at the Grammy Awards. In addition to performing as a solo sitarist, her compositional work has led to cross-cultural collaborations with artists such as Sting, M.I.A., Herbie Hancock, Pepe Habichuela, Karsh Kale, Rodrigo y Gabriela, and Joshua Bell, demonstrating the versatility of the sitar across musical genres. -

Anoushka Shankar: Breathing Under Water – ‘Burn’, ‘Breathing Under Water’ and ‘Easy’ (For Component 3: Appraising)

Anoushka Shankar: Breathing Under Water – ‘Burn’, ‘Breathing Under Water’ and ‘Easy’ (For component 3: Appraising) Background information and performance circumstances The composer Anoushka Shankar was born in 1981, in London, and is the daughter of the famous sitar player Ravi Shankar. She was brought up in London, Delhi and California, where she attended high school. She studied sitar with her father from the age of 7, began playing tampura in his concerts at 10, and gave her first solo sitar performances at 13. She signed her first recording contract at 16 and her first three album releases were of Indian Classical performances. Her first cross-over/fusion album – Rise – was released in 2005 and was nominated for a Grammy, in the Contemporary World Music category. Her albums since Breathing Under Water have continued to explore the connections between Indian music and other styles. She has collaborated with some major artists – Sting, Nithin Sawhney, Joshua Bell and George Harrison, as well as with her father, Ravi Shankar, and her half-sister, Norah Jones. She has also performed around the world as a Classical sitar player – playing her father’s sitar concertos with major orchestras. The piece Breathing Under Water was Anoushka Shankar’s fifth album, and her second of original fusion music. Her main collaborator was Utkarsha (Karsh) Kale, an Indian musician and composer and co-founder of Tabla Beat Science – an Indian band exploring ambient, drum & bass and electronica in a Hindustani music setting. Kale contributes dance music textures and technical expertise, as well as playing tabla, drums and guitar on the album. -

Fusion Without Confusion Raga Basics Indian

Fusion Without Confusion Raga Basics Indian Rhythm Basics Solkattu, also known as konnakol is the art of performing percussion syllables vocally. It comes from the Carnatic music tradition of South India and is mostly used in conjunction with instrumental music and dance instruction, although it has been widely adopted throughout the world as a modern composition and performance tool. Similarly, the music of North India has its own system of rhythm vocalization that is based on Bols, which are the vocalization of specific sounds that correspond to specific sounds that are made on the drums of North India, most notably the Tabla drums. Like in the south, the bols are used in musical training, as well as composition and performance. In addition, solkattu sounds are often referred to as bols, and the practice of reciting bols in the north is sometimes referred to as solkattu, so the distinction between the two practices is blurred a bit. The exercises and compositions we will discuss contain bols that are found in both North and South India, however they come from the tradition of the North Indian tabla drums. Furthermore, the theoretical aspect of the compositions is distinctly from the Hindustani, (north Indian) tradition. Hence, for the purpose of this presentation, the use of the term Solkattu refers to the broader, more general practice of Indian rhythmic language. South Indian Percussion Mridangam Dolak Kanjira Gattam North Indian Percussion Tabla Baya (a.k.a. Tabla) Pakhawaj Indian Rhythm Terms Tal (also tala, taal, or taala) – The Indian system of rhythm. Tal literally means "clap". -

The Rich Heritage of Dhrupad Sangeet in Pushtimarg On

Copyright © 2006 www.vallabhkankroli.org - All Rights Reserved by Shree Vakpati Foundation - Baroda ||Shree DwaDwarrrrkeshokesho Jayati|| || Shree Vallabhadhish Vijayate || The Rich Heritage Of Dhrupad Sangeet in Pushtimarg on www.vallabhkankroli.org Reference : 8th Year Text Book of Pushtimargiya Patrachaar by Shree Vakpati Foundation - Baroda Inspiration: PPG 108 Shree Vrajeshkumar Maharajshri - Kankroli PPG 108 Shree Vagishkumar Bawashri - Kankroli Copyright © 2006 www.vallabhkankroli.org - All Rights Reserved by Shree Vakpati Foundation - Baroda Contents Meaning of Sangeet ........................................................................................................................... 4 Naad, Shruti and Swar ....................................................................................................................... 4 Definition of Raga.............................................................................................................................. 5 Rules for Defining Ragas................................................................................................................... 6 The Defining Elements in the Raga................................................................................................... 7 Vadi, Samvadi, Anuvadi, Vivadi [ Sonant, Consonant, Assonant, Dissonant] ................................ 8 Aroha, avaroha [Ascending, Descending] ......................................................................................... 8 Twelve Swaras of the Octave ........................................................................................................... -

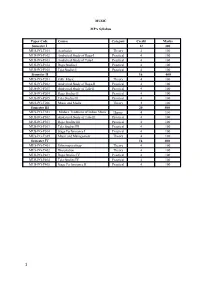

MUSIC MPA Syllabus Paper Code Course Category Credit Marks

MUSIC MPA Syllabus Paper Code Course Category Credit Marks Semester I 12 300 MUS-PG-T101 Aesthetics Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P102 Analytical Study of Raga-I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P103 Analytical Study of Tala-I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P104 Raga Studies I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P105 Tala Studies I Practical 4 100 Semester II 16 400 MUS-PG-T201 Folk Music Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P202 Analytical Study of Raga-II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P203 Analytical Study of Tala-II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P204 Raga Studies II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P205 Tala Studies II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-T206 Music and Media Theory 4 100 Semester III 20 500 MUS-PG-T301 Modern Traditions of Indian Music Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P302 Analytical Study of Tala-III Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P303 Raga Studies III Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P303 Tala Studies III Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P304 Stage Performance I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-T305 Music and Management Theory 4 100 Semester IV 16 400 MUS-PG-T401 Ethnomusicology Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-T402 Dissertation Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P403 Raga Studies IV Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P404 Tala Studies IV Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P405 Stage Performance II Practical 4 100 1 Semester I MUS-PG-CT101:- Aesthetic Course Detail- The course will primarily provide an overview of music and allied issues like Aesthetics. The discussions will range from Rasa and its varieties [According to Bharat, Abhinavagupta, and others], thoughts of Rabindranath Tagore and Abanindranath Tagore on music to aesthetics and general comparative. -

University of Mauritius Mahatma Gandhi Institute

University of Mauritius Mahatma Gandhi Institute Regulations And Programme of Studies B. A (Hons) Performing Arts (Vocal Hindustani) (Review) - 1 - UNIVERSITY OF MAURITIUS MAHATMA GANDHI INSTITUTE PART I General Regulations for B.A (Hons) Performing Arts (Vocal Hindustani) 1. Programme title: B.A (Hons) Performing Arts (Vocal Hindustani) 2. Objectives To equip the student with further knowledge and skills in Vocal Hindustani Music and proficiency in the teaching of the subject. 3. General Entry Requirements In accordance with the University General Entry Requirements for admission to undergraduate degree programmes. 4. Programme Requirement A post A-Level MGI Diploma in Performing Arts (Vocal Hindustani) or an alternative qualification acceptable to the University of Mauritius. 5. Programme Duration Normal Maximum Degree (P/T): 2 years 4 years (4 semesters) (8 semesters) 6. Credit System 6.1 Introduction 6.1.1 The B.A (Hons) Performing Arts (Vocal Hindustani) programme is built up on a 3- year part time Diploma, which accounts for 60 credits. 6.1.2 The Programme is structured on the credit system and is run on a semester basis. 6.1.3 A semester is of a duration of 15 weeks (excluding examination period). - 2 - 6.1.4 A credit is a unit of measure, and the Programme is based on the following guidelines: 15 hours of lectures and / or tutorials: 1 credit 6.2 Programme Structure The B.A Programme is made up of a number of modules carrying 3 credits each, except the Dissertation which carries 9 credits. 6.3 Minimum Credits Required for the Award of the Degree: 6.3.1 The MGI Diploma already accounts for 60 credits. -

Rajeeb Chakraborty (Sarod) and Reena Shrivastava

The Asian Indian Classical Music Society 52318 N Tally Ho Drive, South Bend, IN 46635 Indian Classical Music Concert Dr. Rajeeb Chakarborty (sarod) Reena Chakraborty Shrivastava (sitar) with Subhen Chatterjee (tabla) September 6, 2009, Sunday, 7.30PM Dr. Rajeeb Chakraborty and Reena Chakraborty Shrivastava, are two of India’s leading classical instrumental musicians. They started training with their father, the eminent Sarod player, Pandit Robi Chakraborty, from the ages of six and five. They belong to the famous Maihar Gharana (school or tradition of music), following the tradition of the great masters Ustad Allauddin Khan, Ustad Ali Akbar Khan and Pandit Ravi Shankar. Both Rajeeb and Reena began performing publicly when they were nine years of age. As soloists, and sometimes together, they have participated in all the major music festivals in India, performed extensively in India, the US, Canada, and Western Europe, and have several musical recordings to their names. Subhen Chatterjee has accompanied most of India’s classical musicians. For more information, see http://www.rajeebchakraborty.com/ and http://www.aimusic.co.uk/artiste.html, and for a preview of their music, see http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q57Oh3Ddnk8 Place: the Hesburgh Center for International and Peace Studies Auditorium, University of Notre Dame Tickets available at gate. General Admission: $10, AICMS Members and ND/SMC faculty: $5, Students: FREE Please also note that the AICMS had its annual general-body meeting on June 19, 2009. The new members of the Executive Committee were elected at the meeting. They are: Samir Bose (President), Vidula Agtey (Vice President), Amitava Dutt (Secretary), Ganesh Vaidyanathan (Treasurer) and Umesh Garg (Member-at-Large and Program Coordinator). -

Toccata Classics TOCC0024 Notes

P JULIUS RÖNTGEN, CHAMBER MUSIC, VOLUME ONE – WORKS FOR VIOLIN AND PIANO I by Malcolm MacDonald Considering his prominence in the development of Dutch concert music, and that he was considered by many of his most distinguished contemporaries to possess a compositional talent bordering on genius, the neglect that enveloped the huge output of Julius Röntgen for nearly seventy years after his death seems well-nigh inexplicable, or explicable only to the kind of aesthetic view that had heard of him as stylistically conservative, and equated conservatism as uninteresting and therefore not worth investigating. The recent revival of interest in his works has revealed a much more complex picture, which may be further filled in by the contents of the present CD. A distant relative of the physicist Conrad Röntgen,1 the discoverer of X-rays, Röntgen was born in 1855 into a highly musical family in Leipzig, a city with a musical tradition that stretched back to J. S. Bach himself in the first half of the eighteenth century, and that had been a byword for musical excellence and eminence, both in performance and training, since Mendelssohn’s directorship of the Gewandhaus Orchestra and the Leipzig Conservatoire in the 1830s and ’40s. Röntgen’s violinist father Engelbert, originally from Deventer in the Netherlands, was a member of the Gewandhaus Orchestra and its concert-master from 1873. Julius’ German mother was the pianist Pauline Klengel, sister of the composer Julius Klengel (father of the cellist-composer of the same name), who became his nephew’s principal tutor; the whole family belonged to the circle around the composer and conductor Heinrich von Herzogenberg and his wife Elisabet, whose twin passions were the revival of works by Bach and the music of their close friend Johannes Brahms. -

List of Empanelled Artist

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT ARTISTS S.No. Name of Artist/Group State Date of Genre Contact Details Year of Current Last Cooling off Social Media Presence Birth Empanelment Category/ Sponsorsred Over Level by ICCR Yes/No 1 Ananda Shankar Jayant Telangana 27-09-1961 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-40-23548384 2007 Outstanding Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwH8YJH4iVY Cell: +91-9848016039 September 2004- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vrts4yX0NOQ [email protected] San Jose, Panama, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDwKHb4F4tk [email protected] Tegucigalpa, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SIh4lOqFa7o Guatemala City, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiOhl5brqYc Quito & Argentina https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COv7medCkW8 2 Bali Vyjayantimala Tamilnadu 13-08-1936 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44-24993433 Outstanding No Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbT7vkbpkx4 +91-44-24992667 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKvILzX5mX4 [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kyQAisJKlVs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6S7GLiZtYQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WBPKiWdEtHI 3 Sucheta Bhide Maharashtra 06-12-1948 Bharatanatyam Cell: +91-8605953615 Outstanding 24 June – 18 July, Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WTj_D-q-oGM suchetachapekar@hotmail 2015 Brazil (TG) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOhzx_npilY .com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SgXsRIOFIQ0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSepFLNVelI 4 C.V.Chandershekar Tamilnadu 12-05-1935 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44- 24522797 1998 Outstanding 13 – 17 July 2017- No https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ec4OrzIwnWQ -

A NOTE from Johnstone-Music

A NOTE FROM Johnstone-Music ABOUT THE MAIN ARTICLE STARTING ON THE FOLLOWING PAGE: We are pleased for you to have a copy of this article, which you may read, print or saved on your computer. These presentations can be downloaded directly. You are free to make any number of additional photocopies, for Johnstone-Music seeks no direct financial gain whatsoever from these articles (and neither too the writers with their generous contributions); however, we ask that the name of Johnstone-Music be mentioned if any document is reproduced. If you feel like sending any (hopefully favourable!) comment visit the ‘Contact’ section of the site and leave a message with the details - we will be delighted to hear from you! SPECIAL FEATURE on JOHN FOULDS .. Birth: 2nd November 1880 - Hulme, Manchester, England Death: 25th April 1939 - Delhi, India .. .. Born into a musical family, Foulds learnt piano and cello from a young age, playing the latter in the Hallé Orchestra from 1990 with his father, who was a bassoonist in the same orchestra. He was also a member of Promenade and Theatre bands. .. Simultaneously with cello career he was an important composer of theatre music. Notable works for our instrument included a cello concerto and a cello sonata. Suffering a setback after the decline in popularity of his World Requiem (1919–1921), he left London for Paris in 1927, and eventually travelled to India in 1935 where, among other things, he collected folk music, composed pieces for traditional Indian instrument ensembles, and worked as Director of European Music for All-India Radio in Delhi. -

Stephen M. Slawek Curriculum Vitae

Stephen M. Slawek Curriculum Vitae 10008 Sausalito Drive Butler School of Music Austin, TX 78759-6106 The University of Texas at Austin (512) 794-2981 Austin, TX. 78712-0435 (512) 471-0671 Education 1986 Ph.D. (Ethnomusicology) University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 1978 M.A. (Ethnomusicology) University of Hawaii at Manoa 1976 M. Mus. (Sitar) Banaras Hindu University 1974 B. Mus. (Sitar) Banaras Hindu University 1973 Diploma (Tabla) Banaras Hindu University 1971 B.A. (Biology) University of Pennsylvania Employment 1999-present Professor of Ethnomusicology, The University of Texas at Austin 2000 Visiting Professor, Rice University, Hanzsen and Lovett College 1989-1999 Associate Professor of Ethnomusicology and Asian Studies, The University of Texas at Austin 1985-1989 Assistant Professor of Ethnomusicology and Asian Studies, The University of Texas at Austin 1983-1985 Instructor of Ethnomusicology and Asian Studies, The University of Texas at Austin 1983 Visiting Lecturer of Ethnomusicology, University of Illinois at Urbana- Champaign 1982 Graduate Assistant, School of Music, University of Illinois at Urbana- Champaign 1978-1980 Archivist, Archives of Ethnomusicology, School of Music, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Scholarship and Creative Activities Books under contract The Classical Music of India: Going Global with Ravi Shankar. New York and London: Routledge Press. 1997 Musical Instruments of North India: Eighteenth Century Portraits by Baltazard Solvyns. Delhi: Manohar Publishers. Pp. i-vi and 1-153. (with Robert L. Hardgrave) SLAWEK- curriculum vitae 2 1987 Sitar Technique in Nibaddh Forms. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, Indological Publishers and Booksellers. Pp. i-xix and 1-232. Articles in scholarly journals 1996 In Raga, in Tala, Out of Culture?: Problems and Prospects of a Hindustani Musical Transplant in Central Texas.