The Significance of North East India in the Development of the Sculpture of Bagan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nalanda University: a University for the 21St Century

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE Nalanda University: A University for the 21st Century Anjana Sharma The name Nalanda is an icon for cross-cultural interactions and intra-regional connectivity around the globe. Located in Bihar, India, near the site where the Buddha attained enlightenment, the centre of learning at Nalanda was a major hub for educational and intellectual exchange and the creation and dissemination of knowledge among Asian societies from the fifth to the twelfth centuries CE. It received students from across Asia, stimulated intellectual, scientific, and religious dialogues, and dispatched missionaries and scholars to the leading Buddhist centres of Asia. Later generations have called this centre of learning “Nalanda University” and described it as the world’s first educational institution of higher learning. When after an eight hundred year existence it was destroyed by an act of war, Nalanda lived on for another eight hundred years only in the shared cultural memory of India and Asian countries. It stood as a living symbol of a time of an inter connected Asia, of an Asia that did not then define itself against the paradigms of the emergent and monolithic model of higher education that holds sway today. Uncomfortable though this fact may be, what we have to accept today is faultlines created by the overwhelming force of multiple colonialisms—across Asian countries—that have altered the way we establish universities and has given to us today, what can only be decribed unflatteringly, as an imitative Asian model of the university. -

Book Reviews - Matthew Amster, Jérôme Rousseau, Kayan Religion; Ritual Life and Religious Reform in Central Borneo

Book Reviews - Matthew Amster, Jérôme Rousseau, Kayan religion; Ritual life and religious reform in Central Borneo. Leiden: KITLV Press, 1998, 352 pp. [VKI 180.] - Atsushi Ota, Johan Talens, Een feodale samenleving in koloniaal vaarwater; Staatsvorming, koloniale expansie en economische onderontwikkeling in Banten, West-Java, 1600-1750. Hilversum: Verloren, 1999, 253 pp. - Wanda Avé, Johannes Salilah, Traditional medicine among the Ngaju Dayak in Central Kalimantan; The 1935 writings of a former Ngaju Dayak Priest, edited and translated by A.H. Klokke. Phillips, Maine: Borneo Research Council, 1998, xxi + 314 pp. [Borneo Research Council Monograph 3.] - Peter Boomgaard, Sandra Pannell, Old world places, new world problems; Exploring issues of resource management in eastern Indonesia. Canberra: Centre for Resource and Environmental Studies, Australian National University, 1998, xiv + 387 pp., Franz von Benda-Beckmann (eds.) - H.J.M. Claessen, Geoffrey M. White, Chiefs today; Traditional Pacific leadership and the postcolonial state. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1997, xiv + 343 pp., Lamont Lindstrom (eds.) - H.J.M. Claessen, Judith Huntsman, Tokelau; A historical ethnography. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 1996, xii + 355 pp., Antony Hooper (eds.) - Hans Gooszen, Gavin W. Jones, Indonesia assessment; Population and human resources. Canberra: Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, Australian National University, 1997, 73 pp., Terence Hull (eds.) - Rens Heringa, John Guy, Woven cargoes; Indian textiles in the East. London: Thames and Hudson, 1998, 192 pp., with 241 illustrations (145 in colour). - Rens Heringa, Ruth Barnes, Indian block-printed textiles in Egypt; The Newberry collection in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1997. Volume 1 (text): xiv + 138 pp., with 32 b/w illustrations and 43 colour plates; Volume 2 (catalogue): 379 pp., with 1226 b/w illustrations. -

Lord Buddha in the Cult of Lord Jagannath

June - 2014 Odisha Review Lord Buddha in the Cult of Lord Jagannath Abhimanyu Dash he Buddhist origin of Lord Jagannath was (4) At present an image of Buddha at Ellora Tfirst propounded by General A. Cunningham is called Jagannath which proves Jagannath and which was later on followed by a number of Buddha are identical. scholars like W.W.Hunter, W.J.Wilkins, (5) The Buddhist celebration of the Car R.L.Mitra, H.K. Mahatab, M. Mansingh, N. K. Festival which had its origin at Khotan is similar Sahu etc. Since Buddhism was a predominant with the famous Car Festival of the Jagannath cult. religion of Odisha from the time of Asoka after (6) Indrabhuti in his ‘Jnana Siddhi’ has the Kalinga War, it had its impact on the life, referred to Buddha as Jagannath. religion and literature of Odisha. Scholars have (7) There are similar traditions in Buddhism made attempt to show the similarity of Jagannath as well as in the Jagannath cult. Buddhism was cult with Buddhism on the basis of literary and first to discard caste distinctions. So also there is archaeological sources. They have put forth the no caste distinction in the Jagannath temple at the following arguments to justify the Buddhist origin time of taking Mahaprasad. This has come from of Lord Jagannath. the Buddhist tradition. (1) In their opinion the worship of three (8) On the basis of the legend mentioned in symbols of Buddhism, Tri-Ratna such as the the ‘Dathavamsa’ of Dharmakirtti of Singhala, Buddha, the Dhamma (Dharma) and the Sangha scholars say that a tooth of Buddha is kept in the body of Jagannath. -

My Forays Into the World of the Tablä†

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Spring 2014 My Forays into the World of the Tablā Madeline Longacre SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Longacre, Madeline, "My Forays into the World of the Tablā" (2014). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 1814. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/1814 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MY FORAYS INTO THE WORLD OF THE TABL Ā Madeline Longacre Dr. M. N. Storm Maria Stallone, Director, IES Abroad Delhi SIT: Study Abroad India National Identity and the Arts Program, New Delhi Spring 2014 TABL Ā OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ………………………………………………………………………………………....3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ……………………………………………………………………………..4 DEDICATION . ………………………………………………………………………………...….....5 INTRODUCTION ………………………………………………………………………………….....6 WHAT MAKES A TABL Ā……………………………………………………………………………7 HOW TO PLAY THE TABL Ā…………………………………………………………………………9 ONE CITY , THREE NAMES ………………………………………………………………………...11 A HISTORY OF VARANASI ………………………………………………………………………...12 VARANASI AS A MUSICAL CENTER ……………………………………………………………….14 THE ORIGINS OF THE TABL Ā……………………………………………………………………...15 -

Downloaded From

J. van Lohuizen-de Leeuw Which European first recorded the unique Dvarapala of Barabudur? In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 138 (1982), no: 2/3, Leiden, 285-294 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com09/24/2021 08:35:46PM via free access J. E. VAN LOHUIZEN-DE LEEUW WHICH EUROPEAN FIRST RECORDED THE UNIQUE DVARAPALA OF BARABUDUR? In 1910 van Erp made an inventory of the Indo-Javanese sculptures which King Chulalongkorn of Thailand was allowed to take back to Bangkok as a memento of his extensive state visit to Indonesia in 1896. Owing to the First World War the article was not published until 1917. In 1923 and 1927 he wrote two more articles about this group of sculptures giving additional information. The piece the loss of which he most regretted was the unique dvarapala 1 of Barabudur (see PI. 1). According to van Erp this image was first noticed by an unknown visitor to Barabudur who stayed as a guest with the Resident, C. L. Hartmann, in May 1840.2 This anonymous person made the following note in his diary, which was later published in 1858 3: "A hill almost as high as that on which Boro Boedoer is situated and which rises almost immediately at its foot had for some time attracted my attention. The demang of Probolingo district, who acted as my guide, took me up this hill and told me that he wanted to show me the 'toekan' (architect) of that beautiful temple. For on the top of this hill stood a solid image of the same appearance and in the same attitude as the guardians at Prambanan but considerably smaller (i.e. -

Sacred Space on Earth : (Spaces Built by Societal Facts)

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention ISSN (Online): 2319 – 7722, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 7714 www.ijhssi.org ||Volume 4 Issue 8 || August. 2015 || PP.31-35 Sacred Space On Earth : (Spaces Built By Societal Facts) Dr Jhikmik Kar Rani Dhanya Kumari College, Jiaganj, Murshidabad. Kalyani University. ABSTRACT: To the Hindus the whole world is sacred as it is believed to spring from the very body of God. Hindus call these sacred spaces to be “tirthas” which is the doorway between heaven and earth. These tirthas(sacred spaces) highlights the great act of gods and goddesses as well as encompasses the mythic events surrounding them. It signifies a living sacred geographical space, a place where everything is blessed pure and auspicious. One of such sacred crossings is Shrikshetra Purosottam Shetra or Puri in Orissa.(one of the four abodes of lord Vishnu in the east). This avenue collects a vast array of numerous mythic events related to Lord Jagannatha, which over the centuries attracted numerous pilgrims from different corners of the world and stand in a place empowered by the whole of India’s sacred geography. This sacred tirtha created a sacred ceremonial/circumbulatory path with the main temple in the core and the secondary shrines on the periphery. The mythical/ritual traditions are explained by redefining separate ritual (sacred) spaces. The present study is an attempt to understand their various features of these ritual spaces and their manifestations in reality at modern Puri, a temple town in Orissa, Eastern India. KEYWORDS: sacred geography, space, Jagannatha Temple I. Introduction Puri is one of the most important and famous sacred spaces (TirthaKhetra) of the Hindus. -

8 Days 7 Nights BUDDHIST TOUR Valid NOW – Further Notice

8 Days 7 Nights BUDDHIST TOUR Valid NOW – Further notice Day 01 : Arrive Gaya - Bodhgaya Arrival Gaya Int'l airport. Meeting and Greeting at the airport. Transfer to hotel in Bodhgaya. Bodhgaya is the place of the Buddha's Enlightenment and spiritual home of Buddhists. It attracts many believers from all over the world. Bodhgaya situated near the river Niranjana, is one of the holiest Buddhist pilgrimage centres and in the second place of the four holy sites in Buddhism. Day 02 : Bodhgaya - Rajgir - Nalanda - Patna Morning leave Bodhgaya for Patna (182 kms - 6 hrs) enroute visiting Rajgir and Nalanda. Rajgir is a site of great sanctity and significance for Buddhists. Rajgir is an important Buddhist pilgrimage site since the Buddha spent 12 years here and the first Buddhist council after the Buddha was hosted here at the Saptaparni caves. Afternoon visit Gridhakuta Hill, Bimbisara jail. Drive to Nalanda which is 14 kms drive and it was one of the oldest Universities of the World and International Centre for Buddhist Studies. Drive to Patna which is 90 kms, on arrival at Patna transfer to hotel for overnight stay. Day 03: Patna - Vaishali - Kushinagar Morning proceed to Kushinagar (approx. 256 kms and 07 hrs drive) enroute visiting Vaishali - place where Buddha announced the approaching of his Mahaparinirvana. After that continue drive to Kushinagar (place where Lord Buddha had left the world behind him after offering an invaluable contribution to humanity, the great religion known as Buddhism). On arrival Kushinagar, transfer to hotel. Afternoon visit Mahaparinirvana Temple (where Buddha took his last breathe) and Rambhar Stupa (cremation site of Lord Buddha). -

Cave Architecture in Karnataka 5.1 Do You Know? 5.2 Glossary

Cave Architecture in Karnataka 5.1 Do you know? Description Image Source For some reason, the Hindu (Brahmanical) sects did not take to th rock-cut cave temples as late as 4 century CE In the series of Brahmanical cave temples of Ellora, Elephanta, Badami and Aihole, it is only Cave III at Badami which is assigned the earliest definite date (578 CE) and dynastic affiliation (Chalukyas of Badami) by inscription. 5.2 Glossary Staring Related Term Definition Character Term A Adhishthana Pedestal of a building D Dvarapala Door-guardian K Kamathopasarga Obstacles placed in vein by evil Kamatha or Samvara so as not to allow Parsvanatha to attain supreme knowledge K Kinnara A semi-divine being imagined to have half human half animal body M Mukhamandapa Porch M Mithuna A human couple normally in amorous mood, considered auspicious N Naga-Mithuna A Naga couple S Sabhamandapa A hall V Vidyadhara- A semi-divine couple, capable of moving in air; normally mithuna male carries a sword in hand. 5.3 Web links Web links http://en.www.wikipedia.org/wiki/Badami_cave_temples Asi.nic.in>Monuments>Ticketed Monuments>Karnataka http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OcNWBd2vtztL1 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oRf7uebmSnw http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2ZMGoL http://www.jainglory.com/research/meena-basti 5.4 Bibliography Bibliography George Michel, 2014, Architecture and Art of Early Chalukyas (Badami, Mahakuta, Aihole, Pattadakal), Niyogi publishers, Delhi Harle J.C., 1986, Art and Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent, Penguin publishers, Middlesex Huntington S., 1985, The Art of Ancient India, Weatherhill, New York and Tokyo Rajasekhara S., Karnataka Architecture, Sujata publishers, Dharwad Padigar S.V., 2012, Badami (Heritage Series), Department of Archaeology, Museums and Heritage, Bangalore. -

Ancient Universities in India

Ancient Universities in India Ancient alanda University Nalanda is an ancient center of higher learning in Bihar, India from 427 to 1197. Nalanda was established in the 5th century AD in Bihar, India. Founded in 427 in northeastern India, not far from what is today the southern border of Nepal, it survived until 1197. It was devoted to Buddhist studies, but it also trained students in fine arts, medicine, mathematics, astronomy, politics and the art of war. The center had eight separate compounds, 10 temples, meditation halls, classrooms, lakes and parks. It had a nine-story library where monks meticulously copied books and documents so that individual scholars could have their own collections. It had dormitories for students, perhaps a first for an educational institution, housing 10,000 students in the university’s heyday and providing accommodations for 2,000 professors. Nalanda University attracted pupils and scholars from Korea, Japan, China, Tibet, Indonesia, Persia and Turkey. A half hour bus ride from Rajgir is Nalanda, the site of the world's first University. Although the site was a pilgrimage destination from the 1st Century A.D., it has a link with the Buddha as he often came here and two of his chief disciples, Sariputra and Moggallana, came from this area. The large stupa is known as Sariputra's Stupa, marking the spot not only where his relics are entombed, but where he was supposedly born. The site has a number of small monasteries where the monks lived and studied and many of them were rebuilt over the centuries. We were told that one of the cells belonged to Naropa, who was instrumental in bringing Buddism to Tibet, along with such Nalanda luminaries as Shantirakshita and Padmasambhava. -

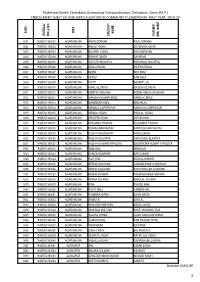

Mahatma Gandhi Chitrakoot Gramodaya Vishwavidyalaya, Chitrakoot, Satna (M.P.)

Mahatma Gandhi Chitrakoot Gramodaya Vishwavidyalaya, Chitrakoot, Satna (M.P.) ENROLLMENT SHEET OF BSW (SPECIALIZATION IN COMMUNITY LEADERSHIP) FIRST YEAR 2019-20 DIST. S.NO. NAME NAME FATHER/ ENROLL/ ROLL NO. STUDENT STUDENT HUS. NAME HUS. 0001 19/WE/01350001 AGAR MALWA ANITA GORANA RAJU GORANA 0002 19/WE/01350002 AGAR MALWA ANJALI YADAV DEVENDRA SINGH 0003 19/WE/01350003 AGAR MALWA BASANTI YADAV SHIV NARAYAN 0004 19/WE/01350004 AGAR MALWA BHARAT SINGH DAYARAM 0005 19/WE/01350005 AGAR MALWA GAYATRI MALVEYA MOHANLAL MALVEYA 0006 19/WE/01350006 AGAR MALWA GUNJA RAVAL RAJESH RAVAL 0007 19/WE/01350007 AGAR MALWA INDRA SITA RAM 0008 19/WE/01350008 AGAR MALWA JASSU RAM KALA 0009 19/WE/01350009 AGAR MALWA JYOTI BASANTI LAL 0010 19/WE/01350010 AGAR MALWA KAPIL SILORIYA RAJESH SILORIYA 0011 19/WE/01350011 AGAR MALWA MAMTA CHAUHAN KOMAL SINGH CHAUHAN 0012 19/WE/01350012 AGAR MALWA MANISHA KUMARI BENS NANDLAL BENS 0013 19/WE/01350013 AGAR MALWA NARENDRA SONI MADANLAL 0014 19/WE/01350014 AGAR MALWA NIRMALA CARPENTAR NARAYAN CARPENTAR 0015 19/WE/01350015 AGAR MALWA NIRMLA YADAV PIRULAL YADAV 0016 19/WE/01350016 AGAR MALWA PRAVEEN KHAN JAFAR KHAN 0017 19/WE/01350017 AGAR MALWA PRIYANKA THAKUR RAJENDRA THAKUR 0018 19/WE/01350018 AGAR MALWA PUNAM SHRIVASTAV SANTOSH SHRIVASTAV 0019 19/WE/01350019 AGAR MALWA PUSHPA BAGDAWAT HINDU SINGH 0020 19/WE/01350020 AGAR MALWA PUSHPA BIJORIYA HARI SINGH BIJORIYA 0021 19/WE/01350021 AGAR MALWA PUSHPA KUMARI PIPALDYA BHUPENDRA KUMAR PIPALDYA 0022 19/WE/01350022 AGAR MALWA RAMU BAI MANGILAL 0023 19/WE/01350023 AGAR -

Ancient Nalanda University Dr

Ancient Nalanda University Dr. Manoj Kumar Assistant Professor (Guest) Dept. of A.I.H. & Archaeology, Patna University, Patna- 800005 P.G./ M.A. IVth Semester , Paper- History of Indian Buddhism (E.C.) General introduction • It is situated 7 miles south-west of Biharsharif and 7 miles north of Rajgir. • Buchanan was the first to notice its antiquity and as told by Brahmanas there, he took it to be the site of ancient Kundalapura, the capital of the king Bhimaka, the father of Rukmini. • Buchanan felt that the ruins represented a Buddhist site. • Kittoe who next realized the importance of the site in 1847 and had seen the images at Baragaon mistakenly took the area to be a Br General Introduction • It was Alexander Cunningham who identified the extensive site as Nalanda in 1861-62. • Alexander Cunningham had made some trail digs but carried no large scale excavations. • In 1871 or so, Broadly, the then S.D.O. of Bihar, began excavations on the main mound with 1000 labourers, and within 10 days he laid ware the eastern, western and southern facades of the great temple and published a short reports of the excavations. Nalanda: Center of Buddhist Religion and Learning in Ancient India History of Nalanda goes back to the days of Mahavira and Buddha in 6th century B.C. It was the place of birth and Nirvana of Sariputra, one of the famous disciples of Buddha. The place rose into prominence in 5th century A.D as a great monastic-cum-educational institution for oriental art and learning in the whole Buddhist world attraction students from distant countries including China. -

Reclaiming Buddhist Sites in Modern India: Pilgrimage and Tourism in Sarnath and Bodhgaya

RECLAIMING BUDDHIST SITES IN MODERN INDIA: PILGRIMAGE AND TOURISM IN SARNATH AND BODHGAYA RUTIKA GANDHI Bachelor of Arts, University of Lethbridge, 2014 A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies of the University of Lethbridge in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS Department of Religious Studies University of Lethbridge LETHBRIDGE, ALBERTA, CANADA ©Rutika Gandhi, 2018 RECLAIMING BUDDHIST SITES IN MODERN INDIA: PILGRIMAGE AND TOURISM IN SARNATH AND BODHGAYA RUTIKA GANDHI Date of Defence: August 23, 2018 Dr. John Harding Associate Professor Ph.D. Supervisor Dr. Hillary Rodrigues Professor Ph.D. Thesis Examination Committee Member Dr. James MacKenzie Associate Professor Ph.D. Thesis Examination Committee Member Dr. James Linville Associate Professor Ph.D. Chair, Thesis Examination Committee Dedication This thesis is dedicated to my beloved mummy and papa, I am grateful to my parents for being so understanding and supportive throughout this journey. iii Abstract The promotion of Buddhist pilgrimage sites by the Government of India and the Ministry of Tourism has accelerated since the launch of the Incredible India Campaign in 2002. This thesis focuses on two sites, Sarnath and Bodhgaya, which have been subject to contestations that precede the nation-state’s efforts at gaining economic revenue. The Hindu-Buddhist dispute over the Buddha’s image, the Saivite occupation of the Mahabodhi Temple in Bodhgaya, and Anagarika Dharmapala’s attempts at reclaiming several Buddhist sites in India have led to conflicting views, motivations, and interpretations. For the purpose of this thesis, I identify the primary national and transnational stakeholders who have contributed to differing views about the sacred geography of Buddhism in India.