NARRATIVE COMPONENT in BALLET ART: a Problem Statement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Russia Uncovered: Moscow & St Petersburg

For Expert Advice Call A unique occasion deserves a unique experience. 01722 744 695 https://www.weekendalacarte.co.uk/special-occasion-holidays/destinations/russia/russia-uncovered/ Russia Uncovered: Moscow & St Petersburg Break available: May - September 7 Night Break Highlights With private tours from start to finish you will come away from this holiday having explored two of its greatest cities; St ● Private Hermitage tour with exclusive early access avoiding Petersburg, the Venice of the North, and the Capital Moscow with the queues the dramatic Kremlin at its heart with a day in the countryside at ● Private tour of Peter Paul Fortress with the Romanov family the "Russian Vatican". Experience and contrast the aristocratic tombs beauty of St Petersburg and the confident modern city of Moscow ● Private tour of the beautiful Peterhof Palace with its with as many of the Palaces, Museums and cultural delights as fountains, returning by Hydrofoil you wish as we can tailor-make all our breaks to you. With the ● Private Tour of Catherine's & Paul's palaces with traditional Bolshoi Ballet based in Moscow and the Mariinsky in St Russian tasting menu lunch Petersburg add in a world class ballet performance and you will ● Private River and Canal Floodlight Night Tour to see St indeed come home full to the brim with cultural wonders. This Petersburg Palaces & Cathederals ● private tour allows you to beat the queues into all the historic Private Moscow city floodlight tour ● Private Kremlin tour and visit the Diamond fund sites, to have exclusive early access to the Hermitage so you ● Visit the amazing Moscow Metro with private guide can enjoy its treasures without the crowds, and the ability to ● Visit the Russian Vatican, Sergiev Posad with private guide go at your own pace. -

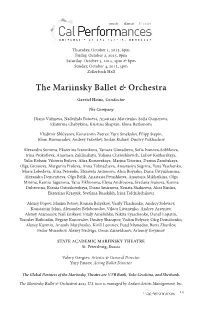

The Mariinsky Ballet & Orchestra

Thursday, October 1, 2015, 8pm Friday, October 2, 2015, 8pm Saturday, October 3, 2015, 2pm & 8pm Sunday, October 4, 2015, 3pm Zellerbach Hall The Mariinsky Ballet & Orchestra Gavriel Heine, Conductor The Company Diana Vishneva, Nadezhda Batoeva, Anastasia Matvienko, Sofia Gumerova, Ekaterina Chebykina, Kristina Shapran, Elena Bazhenova Vladimir Shklyarov, Konstantin Zverev, Yury Smekalov, Filipp Stepin, Islom Baimuradov, Andrey Yakovlev, Soslan Kulaev, Dmitry Pukhachov Alexandra Somova, Ekaterina Ivannikova, Tamara Gimadieva, Sofia Ivanova-Soblikova, Irina Prokofieva, Anastasia Zaklinskaya, Yuliana Chereshkevich, Lubov Kozharskaya, Yulia Kobzar, Viktoria Brileva, Alisa Krasovskaya, Marina Teterina, Darina Zarubskaya, Olga Gromova, Margarita Frolova, Anna Tolmacheva, Anastasiya Sogrina, Yana Yaschenko, Maria Lebedeva, Alisa Petrenko, Elizaveta Antonova, Alisa Boyarko, Daria Ustyuzhanina, Alexandra Dementieva, Olga Belik, Anastasia Petushkova, Anastasia Mikheikina, Olga Minina, Ksenia Tagunova, Yana Tikhonova, Elena Androsova, Svetlana Ivanova, Ksenia Dubrovina, Ksenia Ostreikovskaya, Diana Smirnova, Renata Shakirova, Alisa Rusina, Ekaterina Krasyuk, Svetlana Russkikh, Irina Tolchilschikova Alexey Popov, Maxim Petrov, Roman Belyakov, Vasily Tkachenko, Andrey Soloviev, Konstantin Ivkin, Alexander Beloborodov, Viktor Litvinenko, Andrey Arseniev, Alexey Atamanov, Nail Enikeev, Vitaly Amelishko, Nikita Lyaschenko, Daniil Lopatin, Yaroslav Baibordin, Evgeny Konovalov, Dmitry Sharapov, Vadim Belyaev, Oleg Demchenko, Alexey Kuzmin, Anatoly Marchenko, -

The History of Russian Ballet

Pet’ko Ludmyla, Ph.D., Associate Professor, Dragomanov National Pedagogical University Savina Kateryna Dragomanov National Pedagogical University Institute of Arts, student THE HISTORY OF RUSSIAN BALLET Петько Людмила к.пед.н., доцент НПУ имени М.П.Драгоманова (Украина, г.Киев) Савина Екатерина Национальный педагогический университет имени М.П.Драгоманова (Украина, г.Киев), Інститут искусствб студентка Annotation This article is devoted to describing of history of Russian ballet. The aim of the article is to provide the reader some materials on developing of ballet in Russia, its influence on the development of ballet schools in the world and its leading role in the world ballet art. The authors characterize the main periods of history of Russian ballet and its famous representatives. Key words: Russian ballet, choreographers, dancers, classical ballet, ballet techniques. 1. Introduction. Russian ballet is a form of ballet characteristic of or originating from Russia. In the early 19th century, the theatres were opened up to anyone who could afford a ticket. There was a seating section called a rayok, or «paradise gallery», which consisted of simple wooden benches. This allowed non- wealthy people access to the ballet, because tickets in this section were inexpensive. It is considered one of the most rigorous dance schools and it came to Russia from France. The specific cultural traits of this country allowed to this technique to evolve very fast reach his most perfect state of beauty and performing [4; 22]. II. The aim of work is to investigate theoretical material and to study ballet works on this theme. To achieve the aim we have defined such tasks: 1. -

NEWSLETTER > 2019

www.telmondis.fr NEWSLETTER > 2019 Opera Dance Concert Documentary Circus Cabaret & magic OPERA OPÉRA NATIONAL DE PARIS > Boris Godunov 4 > Don Pasquale 4 > Les Huguenots 6 SUMMARY > Simon Boccanegra 6 OPÉRA DE LYON DANCE > Don Giovanni 7 OPÉRA NATIONAL DE PARIS TEATRO LA FENICE, VENICE > Thierrée / Shechter / Pérez / Pite 12 > Tribute to Jerome Robbins 12 > Tannhäuser 8 > Cinderella 14 > Orlando Furioso 8 > Norma 9 MALANDAIN BALLET CONCERT > Semiramide 9 > Noah 15 OPÉRA NATIONAL DE PARIS DUTCH NATIONAL OPERA MARIINSKY THEATRE, ST. PETERSBURG > Tchaikovsky Cycle (March 27th and May 15th) 18 > Le Nozze de Figaro 10 > Petipa Gala – 200th Birth Anniversary 16 > The 350th Anniversary Inaugural Gala 18 > Der Ring des Nibelungen 11 > Raymonda 16 BASILIQUE CATHÉDRALE DE SAINT-DENIS > Processions 19 MÜNCHNER PHILHARMONIKER > Concerts at Münchner Philharmoniker 19 ZARYADYE CONCERT HALL, MOSCOW > Grand Opening Gala 20 ST. PETERSBURG PHILHARMONIC > 100th Anniversary of Gara Garayev 20 > Gala Concert - 80th Anniversary of Yuri Temirkanov 21 ALHAMBRA DE GRANADA > Les Siècles, conducted by Pablo Heras-Casado 22 > Les Siècles, conducted by François-Xavier Roth 22 > Pierre-Laurent Aimard’s Recital 23 OPÉRA ROYAL DE VERSAILLES > La Damnation de Faust 23 DOCUMENTARY > Clara Haskil, her mystery as a performer 24 > Kreativ, a study in creativity by A. Ekman 24 > Hide and Seek. Elīna Garanča 25 > Alvis Hermanis, the last romantic of Europe 25 > Carmen, Violetta et Mimi, romantiques et fatales 25 CIRCUS > 42nd international circus festival of Monte-Carlo 26 -

Forever • UK 5,00 £ Switzerland 8,00 CHF USA $ Canada 7,00 $; (Euro Zone)

edition ENGLISH n° 284 • the international DANCE magazine TOM 650 CFP) Pina Forever • UK 5,00 £ Switzerland 8,00 CHF USA $ Canada 7,00 $; (Euro zone) € 4,90 9 10 3 4 Editor-in-chief Alfio Agostini Contributors/writers the international dance magazine Erik Aschengreen Leonetta Bentivoglio ENGLISH Edition Donatella Bertozzi Valeria Crippa Clement Crisp Gerald Dowler Marinella Guatterini Elisa Guzzo Vaccarino Marc Haegeman Anna Kisselgoff Dieudonné Korolakina Kevin Ng Jean Pierre Pastori Martine Planells Olga Rozanova On the cover, Pina Bausch’s final Roger Salas work (2009) “Como el musguito en Sonia Schoonejans la piedra, ay, sí, sí, sí...” René Sirvin dancer Anna Wehsarg, Tanztheater Lilo Weber Wuppertal, Santiago de Chile, 2009. Photo © Ninni Romeo Editorial assistant Cristiano Merlo Translations Simonetta Allder Cristiano Merlo 6 News – from the dance world Editorial services, design, web Luca Ruzza 22 On the cover : Advertising Pina Forever [email protected] ph. (+33) 09.82.29.82.84 Bluebeard in the #Metoo era (+39) 011.19.58.20.38 Subscriptions 30 On stage, critics : [email protected] The Royal Ballet, London n° 284 - II. 2020 Les Ballets de Monte-Carlo Hamburg Ballet: “Duse” Hamburg Ballet, John Neumeier Het Nationale Ballet, Amsterdam English National Ballet Paul Taylor Dance Company São Paulo Dance Company La Scala Ballet, Milan Staatsballett Berlin Stanislavsky Ballet, Moscow Cannes Jeune Ballet Het Nationale Ballet: “Frida” BALLET 2000 New Adventures/Matthew Bourne B.P. 1283 – 06005 Nice cedex 01 – F tél. (+33) 09.82.29.82.84 Teac Damse/Keegan Dolan Éditions Ballet 2000 Sarl – France 47 Prix de Lausanne ISSN 2493-3880 (English Edition) Commission Paritaire P.A.P. -

Training News Spring 2016

Spring 2016 Training News Photos: Cover: Cast of Freedom Rider. UMKC Theatre 2015 Inside Front: From Top: Joshua Gilman in The Learned Ladies. TRAINING NEWS UMKC Theatre 2015 Korrie Murphy in WRITERS: PROJECT MANAGER: EDITORS: The Rocky Horror Show. Jamie Alderiso Tom Mardikes Felicia Londré UMKC Theatre 2015 Amanda Davison Cindy Stofiel Andrew Hagerty Collin Vorbeck Alex Ritchie in Wittenberg. Dalton Pierce DESIGN/LAYOUT MANAGER: UMKC Theatre 2015 David Ruis Sarah M. Oliver DESIGNER: Inside Front Facing Page: Collin Vorbeck Kate Mott Mariem Diaz, Frank Oakley, Ethan Zogg and Aishah Ogbeh in Freedom Rider. UMKC Theatre 2015 Collective Collaboration 1 En Charrette 3 Inside Back From Left: Lightning Strikes Twice in Scenic Design 5 Cast of Wittenberg. Illuminating Projections 8 UMKC Theatre 2015 Matt Carter and the Hudson Scenic Studio 10 Frank Lillig and Korrie Professional Educators 12 Murphy in Pericles. Professors Stay Sharp 14 UMKC Theatre 2014 Working Actors 18 A Lasting Bond 20 Michael Thayer in Sound Mandala 22 The Learned Ladies. Graduate Students Strut Their Stuff 23 UMKC Theatre 2015 A National Collaboration 26 Alumni at Work 28 Back: Shaping Stage Managers 35 Cast of Caucasian Chalk Playwrighting: The Art and the Craft 36 Circle. A Vocal Homecoming 37 UMKC Theatre 2014 Fringe With Benefits 39 Above photos courtesy of Dramaturgs on the Rise 41 Brian Paulette UMKC Theatre is composed of a team of creative, educational profes- sionals who work actively in the professional theatre. We build bridg- es. We assist the creative student to make the journey to becoming a creative professional. The practice of the department is to vigorously educate students in the many arts, crafts and traditions of theatre, and to provide a basis for future careers in the creative industries. -

Don Quixote Part 4 Pasitos Pre Ballet

Don Quixote Part 4 Set Design and Art Set Design Don Quixote is set in Spain, both in Barcelona and the countryside. The set for the ballet very is large, with lots of red, yellow, and orange tones. Comprised of intricately painted backdrops, large set pieces, and dramatic lighting. Click to watch how Designer Tim Hatley Describes his design process for Don Quixote for The Royal Ballet Here are some examples of how different ballet companies imagined the Don Quixote sets. The Royal Ballet San Jose Ballet Ballet Met Mikhailovsky Theatre Ballet What kinds of things would you build to create a town square? The countryside? What kinds of considerations might set designers need to make for ballet versus a play? How could lighting alone change the mood on stage? On the next page design your own set and share with us at [email protected]. Don Quixote the ballet Click to watch the full ballet La Scala with Natalia Osipova What did the sets look like? What types of scenery did you notice? How did the set design coordinate with the costume design? The Character Don Quixote served as inspiration for the great visual artists Salvador Dalí and Pablo Picasso. Don Quixote by Pablo Picasso Don Quixote de la Mancha by Salvador Dalí We want to see you art! Send us your drawing inspired by Don Quixote [email protected] Help Don Quixote find the windmill . -

Worldballetday 2020 the Biggest Ever Global Celebration of Dance • Digital Live Stream 29Th October 2020 • View Via

Press Release 27 October 2020 #WorldBalletDay 2020 The Biggest Ever Global Celebration of Dance • Digital live stream 29th October 2020 • View via www.WorldBalletDay.com World Ballet Day 2020 will be the biggest ever celebration of global dance with a staggering 40 dance companies participating in this year’s unique live streamed event. The Australian Ballet, Bolshoi Ballet and The Royal Ballet will be joined by dance companies from across the globe including Singapore Dance, Joburg Ballet, Alvin Ailey Dance Theatre and Ballet Concierto de Puerto Rico. With COVID-19 guidelines changing daily in countries across the globe, the dance world has struggled to return to its stages and rehearsal studios. However, 2020’s World Ballet Day will bring us together, more than ever before, to celebrate our art forms and go exclusively behind the scenes of the world's top ballet companies. Each company will be streaming live rehearsals and bespoke insights in accordance with their respective local COVID-19 guidance. Watch via worldballetday.com or participating companies' Facebook and YouTube pages or via Tencent video in China. The three main host Companies – The Australian Ballet, Bolshoi Ballet and The Royal Ballet – invite audiences to experience morning class which, in the UK, will take place on the iconic Royal Opera House Main Stage. There will be exclusive interviews and access to backstage rehearsals as the Company prepares for The Royal Ballet: Live, the first series of live performances by The Royal Ballet in seven months. The Royal Ballet -

People Premieres Performances

People Mikhail Messerer at the 12 Mikhailovsky Theatre ANDREJ USPENSKI and EMMA KAULDHAR meet the eminent teacher in St Petersburg The Royal Ballet - Valentino Zucchetti in Swan Lake. © Emma Kauldhar by courtesy of the ROH Valentino Zucchetti 18 MIKE DIXON interviews The Royal Ballet's Italian first soloist Premieres 32 Dorothée Gilbert FRANÇOIS FARGUE catches up Geisha 38 with the Paris Opera étoile MIKE DIXON considers Kenneth Tindall's creation for Northern Ballet The Cellist 62 ROBERT PENMAN and AMANDA JENNINGS review two casts of Cathy Marston's new ballet programmed with Dances at a Gathering The Big Hunger 84 MARK BAIRD reviews Trey McIntyre's new work for San Francisco Ballet Performances 24 Swan Lake Patrice Bart AMANDA JENNINGS reviews The Royal 52 Ballet's production of the timeless ballet, LUCY VAN CLEEF talks with the including Reece Clarke's debut as Siegfried Frenchman about his extraordinary career Giselle in Amsterdam Andrew McNicol 42 74 SUSAN POND applauds two newly appointed GERARD DAVIS touches base with the principals in Amsterdam young choreographer making waves contents Front cover: The Royal Ballet - Natalia Osipova and Reece Clarke in Swan Lake. © Emma Kauldhar by courtesy of the ROH 7 ENTRE NOUS 71 AUDITIONS AND JOBS 99 WHAT'S ON 102 PEOPLE PAGE Dance Europe - April 2020 3 ANCE UROPE D E The Sleeping Beauty FOUNDED IN 1995 44 PANDORA BEAUMONT sees an P.O. Box 12661, London E5 9TZ,UK outstanding debut at the Mariinsky Tel: +44 (0)20 8985 7767 www.danceeurope.net Theatre Editor/Photographer Emma Kauldhar [email protected] -

The Fourth German-Russian Week of the Young Researcher

THE FOURTH GERMAN-RUSSIAN WEEK OF THE YOUNG RESEARCHER “GLOBAL HISTORY. GERMAN-RUSSIAN PERSPECTIVES ON REGIONAL STUDIES” Saint Petersburg, October 6–10, 2014 Impressum “The Fourth German-Russian Week of the Young Researcher” Saint Petersburg, October 6–10, 2014 Editors: Dr. Gregor Berghorn, DAAD / DWIH Moscow Dr. Jörn Achterberg, DFG Office Russia / CIS Julia Ilina (DFG) Layout by: “MaWi group” AG / Moskauer Deutsche Zeitung Photos by: DWIH, DFG, SPSU Moscow, December 2014 Printed by: LLC “Tverskoy Pechatny Dvor” Supported by Federal Foreign Office THE FOURTH GERMAN-RUSSIAN WEEK OF THE YOUNG RESEARCHER “GLOBAL HISTORY. GERMAN-RUSSIAN PERSPECTIVES ON REGIONAL STUDIES” Saint Petersburg, October 6–10, 2014 ТABLE OF CONTENTS Table of contents Preface Prof. Dr. Stefan Rinke, Polina Rysakova, Dr. Gregor Berghorn / Dr. Jörn Achterberg 3 Freie Universität Berlin 37 Saint Petersburg State University 58 Prof. Dr. Aleksandr Kubyshkin, Ivan Sablin, Welcoming Addresses Saint Petersburg State University 38 National Research University “Higher School of Economics”, St. Petersburg 59 Prof. Dr. Nikolai Kropachev, Contributions of Young German and Russian Andrey Shadursky, Rector of the Saint Petersburg State University 4 Researchers Saint Petersburg State University 60 Dr. Heike Peitsch, Anna Shcherbakova, Consul General of the Federal Republic of Germany Monika Contreras Saiz, Institute of Latin America, RAS, Moscow 61 in St. Petersburg 6 Freie Universität Berlin 40 Natalia Toganova, Prof. Dr. Margret Wintermantel, Franziska Davies, Institute of World Economy and International President of the DAAD 9 Ludwig-Maximilian University, Munich 41 Relations (IMEMO RAN), Moscow 62 Prof. Dr. Peter Funke, Jürgen Dinkel, Max Trecker, Vice-President of the DFG 13 Justus-Liebig-University Giessen 42 Ludwig-Maximilian University, Munich 64 Dr. -

In the Footsteps of the Tsars in St Petersburg

For Expert Advice Call A unique occasion deserves a unique experience. 01722 744 695 https://www.weekendalacarte.co.uk/special-occasion-holidays/destinations/russia/st-petersburg-private-holiday/ In the Footsteps of the Tsars in St Petersburg Break available: May - September 4 Night Break Highlights Immerse yourself in the romance and turbulence of this magnificent city on this private tour. St Petersburg is a ● Private Hermitage tour with exclusive early access avoiding sophisticated European city with its history and cultural roots in the queues Russia - a fascinating combination worth exploring and ● Private tour of Peter Paul Fortress with the Romanov family understanding with the help of your own private guide. The tombs ● Private tour of the beautiful Peterhof Palace with its Poets, Tsars, Theatres and Palaces will all be brought to life by your private guide who will share their fascinating history on this fountains, returning by Hydrofoil St Petersburg short break. This private tour allows you to beat ● Private Tour of Catherine's & Paul's palaces with traditional the queues into all the historic sites and to have exclusive Russian tasting menu lunch early access to the Hermitage so you can enjoy its treasures ● Private visit of the evocative siege of Leningrad Defence without the crowds - a huge benefit especially in the summer. Museum ● River and Canal Floodlight Night Tour to see St Petersburg Palaces & Cathederals Day by Day Itinerary DAY 1Private Airport Transfer. Private River and Canal Tour to see St Petersburg Cathedrals and Palaces Fly from London Heathrow to St Petersburg where you private driver and guide will meet and transfer you to your chosen hotel for the start of your St Petersburg private tour. -

Saint Petersburg During the White Nights Vasily Petrenko Conducts Eugene Onegin 5 Nights: 18 - 23 July 2014 (PLEASE NOTE NEW DATES!)

Saint Petersburg during the White Nights Vasily Petrenko conducts Eugene Onegin 5 Nights: 18 - 23 July 2014 (PLEASE NOTE NEW DATES!) Cost per person sharing a Twin or Double room £1595 Cost per person in a double room for sole use £1795 Includes: Return air travel from the UK to St Petersburg inc 23kg baggage allowance, 5 nights bed & breakfast at the Courtyard Pushkin Hotel, top price seats for Eugene Onegin & Romeo and Juliet at the Mikhailovsky and one performance (details to be confirmed) at the Mariinsky Theatre or Concert Hall; 4 days of sightseeing and all entrance fees; two dinners and two light lunches. Standard visa service (see important notes overleaf). NOTE - TOUR DATES ARE SLIGHTLY CHANGED TO THOSE IN OUR ADVANCE MAILER Join us during the “White Nights " in Saint Petersburg when Vasily Petrenko will conduct Tchaikovsky's opera Eugene Onegin at the historic Mikhailovsky Theatre. We will return to the Mikhailovsky for a performance of Prokofiev's ballet Romeo et Juliet and also attend a performance by the Mariinsky Orchestra (performance details to be confirmed). The White Nights are the evenings, running from May to the end of July, when the city emerges from long months of cold and darkness and celebrates the brief return of near round-the-clock daylight. Russia’s cultural capital — situated just five degrees south of the Arctic Circle, at the eastern end of the Gulf of Finland — has been welcoming the summer with relief and celebration ever since Peter the Great founded the city in the early 18th century. During our stay we have included sightseeing to all the major sights of the city including St Isaacs Cathedral , the Church of the Saviour on Spilled Blood , the Peter & Paul Fortress and, of course, the Hermitage .