Journal of Military and Veterans' Health

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

San Francisco Reef Divers June 2017 Volume XLV No. 6 1 SUP DIVING

San Francisco Reef Divers June 2017 Volume XLV No. 6 SUP DIVING VS. KAYAK By Mike Staninec urchins and kept looking into cracks and holes for On Saturday, May 20th, some of the dwindling fish, without much luck. After an hour or so Gene and aging freedive contingent of the San Francisco showed up and told me he had been diving in the Reef Divers assembled in Sausalito, eh, that would same cove, just a bit closer to shore. He had his limit be two of us, Gene Kramer and myself. The forecast of abs as well and had not seen any fish. I pointed for Mendocino coast was quite bit rougher than for out a spot where I had seen some small blues earlier Sonoma that day, so we had decided to stay and he said he'd check it out, and jumped back in. I south. We drove up to the coast through Bodega worked the bottom some more, and was very happy Bay, trying to scout to find a medium size China rockfish in a crack, out the conditions which I invited home along the coast, for dinner with my 38 starting at Salmon Special. Creek. The swell We were both ready was supposed to be to head back. I tried 4-5' which is usually various positions on mild, but the surf at my SUP, but it was Salmon Creek did hard to get not look all that comfortable for mild. For the rest of paddling and my the drive the water progress was very was shrouded in fog, slow. -

The Vietnam War an Australian Perspective

THE VIETNAM WAR AN AUSTRALIAN PERSPECTIVE [Compiled from records and historical articles by R Freshfield] Introduction What is referred to as the Vietnam War began for the US in the early 1950s when it deployed military advisors to support South Vietnam forces. Australian advisors joined the war in 1962. South Korea, New Zealand, The Philippines, Taiwan and Thailand also sent troops. The war ended for Australian forces on 11 January 1973, in a proclamation by Governor General Sir Paul Hasluck. 12 days before the Paris Peace Accord was signed, although it was another 2 years later in May 1975, that North Vietnam troops overran Saigon, (Now Ho Chi Minh City), and declared victory. But this was only the most recent chapter of an era spanning many decades, indeed centuries, of conflict in the region now known as Vietnam. This story begins during the Second World War when the Japanese invaded Vietnam, then a colony of France. 1. French Indochina – Vietnam Prior to WW2, Vietnam was part of the colony of French Indochina that included Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam. Vietnam was divided into the 3 governances of Tonkin, Annam, and Cochinchina. (See Map1). In 1940, the Japanese military invaded Vietnam and took control from the Vichy-French government stationing some 30,000 troops securing ports and airfields. Vietnam became one of the main staging areas for Japanese military operations in South East Asia for the next five years. During WW2 a movement for a national liberation of Vietnam from both the French and the Japanese developed in amongst Vietnamese exiles in southern China. -

An Analysis of the Loss of HMAS SYDNEY

An analysis of the loss of HMAS SYDNEY By David Kennedy The 6,830-ton modified Leander class cruiser HMAS SYDNEY THE MAIN STORY The sinking of cruiser HMAS SYDNEY by disguised German raider KORMORAN, and the delayed search for all 645 crew who perished 70 years ago, can be attributed directly to the personal control by British wartime leader Winston Churchill of top-secret Enigma intelligence decodes and his individual power. As First Lord of the Admiralty, then Prime Minster, Churchill had been denying top secret intelligence information to commanders at sea, and excluding Australian prime ministers from knowledge of Ultra decodes of German Enigma signals long before SYDNEY II was sunk by KORMORAN, disguised as the Dutch STRAAT MALAKKA, off north-Western Australia on November 19, 1941. Ongoing research also reveals that a wide, hands-on, operation led secretly from London in late 1941, accounted for the ignorance, confusion, slow reactions in Australia and a delayed search for survivors . in stark contrast to Churchill's direct part in the destruction by SYDNEY I of the German cruiser EMDEN 25 years before. Churchill was at the helm of one of his special operations, to sweep from the oceans disguised German raiders, their supply ships, and also blockade runners bound for Germany from Japan, when SYDNEY II was lost only 19 days before the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and Southeast Asia. Covering up of a blunder, or a punitive example to the new and distrusted Labor government of John Curtin gone terribly wrong because of a covert German weapon, can explain stern and brief official statements at the time and whitewashes now, with Germany and Japan solidly within Western alliances. -

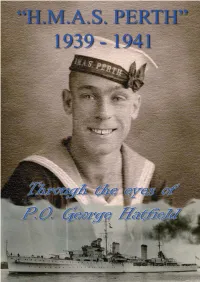

37845R CS3 Book Hatfield's Diaries.Indd

“H.M.A.S. PERTH” 1939 -1941 From the diaries of P.O. George Hatfield Published in Sydney Australia in 2009 Publishing layout and Cover Design by George Hatfield Jnr. Printed by Springwood Printing Co. Faulconbridge NSW 2776 1 2 Foreword Of all the ships that have flown the ensign of the Royal Australian Navy, there has never been one quite like the first HMAS Perth, a cruiser of the Second World War. In her short life of just less than three years as an Australian warship she sailed all the world’s great oceans, from the icy wastes of the North Atlantic to the steamy heat of the Indian Ocean and the far blue horizons of the Pacific. She survived a hurricane in the Caribbean and months of Italian and German bombing in the Mediterranean. One bomb hit her and nearly sank her. She fought the Italians at the Battle of Matapan in March, 1941, which was the last great fleet action of the British Royal Navy, and she was present in June that year off Syria when the three Australian services - Army, RAN and RAAF - fought together for the first time. Eventually, she was sunk in a heroic battle against an overwhelming Japanese force in the Java Sea off Indonesia in 1942. Fast and powerful and modern for her times, Perth was a light cruiser of some 7,000 tonnes, with a main armament of eight 6- inch guns, and a top speed of about 34 knots. She had a crew of about 650 men, give or take, most of them young men in their twenties. -

The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles

The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles The Chinese Navy Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles Saunders, EDITED BY Yung, Swaine, PhILLIP C. SAUNderS, ChrISToPher YUNG, and Yang MIChAeL Swaine, ANd ANdreW NIeN-dzU YANG CeNTer For The STUdY oF ChINeSe MilitarY AffairS INSTITUTe For NATIoNAL STrATeGIC STUdIeS NatioNAL deFeNSe UNIverSITY COVER 4 SPINE 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY COVER.indd 3 COVER 1 11/29/11 12:35 PM The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 1 11/29/11 12:37 PM 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 2 11/29/11 12:37 PM The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles Edited by Phillip C. Saunders, Christopher D. Yung, Michael Swaine, and Andrew Nien-Dzu Yang Published by National Defense University Press for the Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs Institute for National Strategic Studies Washington, D.C. 2011 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 3 11/29/11 12:37 PM Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Department of Defense or any other agency of the Federal Government. Cleared for public release; distribution unlimited. Chapter 5 was originally published as an article of the same title in Asian Security 5, no. 2 (2009), 144–169. Copyright © Taylor & Francis Group, LLC. Used by permission. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Chinese Navy : expanding capabilities, evolving roles / edited by Phillip C. Saunders ... [et al.]. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. -

Naval Documents of the American Revolution

Naval Documents of The American Revolution Volume 4 AMERICAN THEATRE: Feb. 19, 1776–Apr. 17, 1776 EUROPEAN THEATRE: Feb. 1, 1776–May 25, 1776 AMERICAN THEATRE: Apr. 18, 1776–May 8, 1776 Part 7 of 7 United States Government Printing Office Washington, 1969 Electronically published by American Naval Records Society Bolton Landing, New York 2012 AS A WORK OF THE UNITED STATES FEDERAL GOVERNMENT THIS PUBLICATION IS IN THE PUBLIC DOMAIN. MAY 1776 1413 5 May (Sunday) JOURNAL OF H.M. SLOOPHunter, CAPTAINTHOMAS MACKENZIE May 1776 ' Remarks &c in Quebec 1776 Sunday 5 at 5 A M Arrived here his Majestys Sloop surprize at 8 the surprise & Sloop Martin with part of the 29th regt landed with their Marines Light Breezes & fair Sally'd out & drove the rebels off took at different places several pieces of Cannon some Howitzers & a Quantity of Ammunition 1. PRO, Admiralty 511466. JOURNALOF H.M.S. Surprize, CAPTAINROBERT LINZEE May 1776 Runing up the River [St. Lawrence] - Sunday 5. at 4 AM. Weigh'd and came to sail, at 9 Got the Top Chains up, and Slung the yards the Island of Coudre NEBE, & Cape Tor- ment SW1/2W. off Shore 1% Mile. At 10 Came too with the Best Bower in 11 fms. of Water, Veer'd to 1/2 a Cable. at 11 Employ'd racking the Lanyards of the Shrouds, and getting every thing ready for Action. Most part little Wind and Cloudy, Remainder Modre and hazey, at 2 [P.M.] Weigh'd and came to sail, Set Studding sails, nock'd down the Bulk Heads of the Cabbin at 8 PM Came too with the Best Bower in 13 £ms Veer'd to % of a Cable fir'd 19 Guns Signals for the Garrison of Quebec. -

Coastal Command in the Second World War

AIR POWER REVIEW VOL 21 NO 1 COASTAL COMMAND IN THE SECOND WORLD WAR By Professor John Buckley Biography: John Buckley is Professor of Military History at the University of Wolverhampton, UK. His books include The RAF and Trade Defence 1919-1945 (1995), Air Power in the Age of Total War (1999) and Monty’s Men: The British Army 1944-5 (2013). His history of the RAF (co-authored with Paul Beaver) will be published by Oxford University Press in 2018. Abstract: From 1939 to 1945 RAF Coastal Command played a crucial role in maintaining Britain’s maritime communications, thus securing the United Kingdom’s ability to wage war against the Axis powers in Europe. Its primary role was in confronting the German U-boat menace, particularly in the 1940-41 period when Britain came closest to losing the Battle of the Atlantic and with it the war. The importance of air power in the war against the U-boat was amply demonstrated when the closing of the Mid-Atlantic Air Gap in 1943 by Coastal Command aircraft effectively brought victory in the Atlantic campaign. Coastal Command also played a vital role in combating the German surface navy and, in the later stages of the war, in attacking Germany’s maritime links with Scandinavia. Disclaimer: The views expressed are those of the authors concerned, not necessarily the MOD. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form without prior permission in writing from the Editor. 178 COASTAL COMMAND IN THE SECOND WORLD WAR introduction n March 2004, almost sixty years after the end of the Second World War, RAF ICoastal Command finally received its first national monument which was unveiled at Westminster Abbey as a tribute to the many casualties endured by the Command during the War. -

Perth Scuba News 09Jan10

Perth Scuba News www.perthscuba.com Tel: 08 9455 4448 The Manta Club Newsletter Page 1 Issue 91 9th January 2010 WHAT’S COMING UP? • Become a PADI Scuba God!!! Contact Lee on 9455 4448 or email [email protected] SEA & SEA DX-1200HD to discuss becoming a True hi-definition video in this compact camera makes the DX-1200HD a PADI Open Water Scuba Instructor. Find modern marvel. Choose to shoot photos or HD movies to share. out about getting a Camera features include: new job that you truly enjoy and is so much • High definition CCD with 12.19 effective megapixels and 3x optical zoom fun. lens. • Instructor • Features Sea & Sea mode, for brilliant underwater images. Development • Movie function up to 1280x720 pixels (HD video) at 30 frames/ Course begins second. 29th January 2010 $995 • Strong and durable build with a depth rating up to 45 metres. • Wide angle and close up lens accessories available - a big bonus! • Large monitor allows you to check the smallest details in your pictures as you take them. • Light and compact design allows you to use for marine sports in general, plus outdoors winter sports. We recommend this camera for all underwater digital photographers, from novice all the way up to advanced. IN STOCK NOW - COME IN & SEE THEM FOR YOURSELF! cruising past you? Perth Scuba can get you there with heaps of upcoming trips to a multitude of locations all over the world. Meet at Perth Scuba and we’ll show you some of the exciting places we’re visiting over the next 2 years. -

Semaphore Sea Power Centre - Australia Issue 8, 2017 the Royal Australian Navy on the Silver Screen

SEMAPHORE SEA POWER CENTRE - AUSTRALIA ISSUE 8, 2017 THE ROYAL AUSTRALIAN NAVY ON THE SILVER SCREEN In this day and age, technologies such as smart phones and tablets allow users to film and view video streams on almost any topic imaginable at the convenience of their fingertips. Indeed, most institutions, including the Royal Australian Navy (RAN), promote video streaming as part of carefully coordinated public relations, recruiting and social media programs. In yesteryear, however, this was not a simple process and the creation and screening of news reels, motion pictures and training films was a costly and time consuming endeavor for all concerned. Notwithstanding that, the RAN has enjoyed an ongoing presence on the silver screen, television and more recently the internet on its voyage from silent pictures to the technologically advanced, digital 21st century. The RAN’s earliest appearances in motion pictures occurred during World War 1. The first of these films was Sea Dogs of Australia, a silent picture about an Australian naval officer blackmailed into helping a foreign spy. The film’s public release in August 1914 coincided with the outbreak of war and it was consequently withdrawn after the Minister for Defence expressed security concerns over film footage taken on board the battlecruiser HMAS Australia (I). There was, however, an apparent change of heart following the victory of HMAS Sydney (I) over the German cruiser SMS Emden in November 1914. Australia’s first naval victory at sea proved big news around the globe The Art Brand Productions - The Raider Emden. and it did not take long before several short, silent propaganda films were produced depicting the action. -

'The Admiralty War Staff and Its Influence on the Conduct of The

‘The Admiralty War Staff and its influence on the conduct of the naval between 1914 and 1918.’ Nicholas Duncan Black University College University of London. Ph.D. Thesis. 2005. UMI Number: U592637 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U592637 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 CONTENTS Page Abstract 4 Acknowledgements 5 Abbreviations 6 Introduction 9 Chapter 1. 23 The Admiralty War Staff, 1912-1918. An analysis of the personnel. Chapter 2. 55 The establishment of the War Staff, and its work before the outbreak of war in August 1914. Chapter 3. 78 The Churchill-Battenberg Regime, August-October 1914. Chapter 4. 103 The Churchill-Fisher Regime, October 1914 - May 1915. Chapter 5. 130 The Balfour-Jackson Regime, May 1915 - November 1916. Figure 5.1: Range of battle outcomes based on differing uses of the 5BS and 3BCS 156 Chapter 6: 167 The Jellicoe Era, November 1916 - December 1917. Chapter 7. 206 The Geddes-Wemyss Regime, December 1917 - November 1918 Conclusion 226 Appendices 236 Appendix A. -

Royal Australian Navy Vietnam Veterans

Editor: Tony (Doc) Holliday Email: [email protected] Mobile: 0403026916 Volume 1 September 2018 Issue 3 Greenbank Sub Section: News and Events………September / October 2018. Saturday 01 September 2018 1000-1400 Merchant Marine Service Tuesday 04 September 2018 1930-2100 Normal Meeting RSL Rooms Wednesday 26 September 2018 1000 Executive Meeting RSL Rooms Tuesday 02 October 2018 1930-2100 Normal Meeting RSL Rooms Wednesday 31 October 2018 1000 Executive Meeting RSL Rooms Sausage Sizzles: Bunnings, Browns Plains. Friday 14 September 2018 0600-1600 Executive Members of Greenbank Sub. Section President Michael Brophy Secretary Brian Flood Treasurer Henk Winkeler Vice President John Ford Vice President Tony Holliday State Delegate John Ford Vietnam Veterans Service 18August 22018 Service was held at the Greenbank RSL Services Club. Wreath laid by Gary Alridge for Royal Australian Navy Vietnam Veterans. Wreath laid by Michael Brophy on behalf of NAA Sub Section Greenbank. It is with sadness that this issue of the Newsletter announces the passing of our immediate past President and Editor of the Newsletter. Len Kingston-Kerr. Len passed away in his sleep in the early hours of Tuesday 21st August 2018. As per Len’s wishes, there will be no funeral, Len will be cremated at a private service and his ashes scattered at sea by the Royal Australian Navy. A wake will be held at Greenbank RSL in due course. 1 ROYAL AUSTRALIAN NAVY ADMIRALS: Rear Admiral James Vincent Goldrick AO, CSC. James Goldrick was born in Sydney NSW in 1958. He joined the Royal Australian Navy in 1974 as a fifteen-year-old Cadet Midshipman. -

A Spatial Approach to Analyzing Ships of the British Royal Navy During the 18Th and 19Th Centuries

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2015-12-15 Re-imagining Shipboard Societies: A Spatial Approach to Analyzing Ships of the British Royal Navy during the 18th and 19th Centuries Moloney, Michael Joseph Moloney, M. J. (2015). Re-imagining Shipboard Societies: A Spatial Approach to Analyzing Ships of the British Royal Navy during the 18th and 19th Centuries (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/27594 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/2674 doctoral thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Re-imagining Shipboard Societies: A Spatial Approach to Analyzing Ships of the British Royal Navy during the 18th and 19th Centuries by Michael Joseph Moloney A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN ARCHAELOGY CALGARY, ALBERTA DECEMBER, 2015 © Michael J. Moloney 2015 Abstract Investigation into underwater archaeology began, inevitably, with the investigation of shipwrecks. For decades whole divisions of our discipline have focused on studying the intricate characteristics and mechanisms involved in the propulsion, construction, and manipulation of ships themselves (e.g. nautical archaeology). However, as Mortimer Wheeler noted, “the archaeologist is digging up, not things, but people” (Wheeler 1954: 13), so how do we extract information about those crewing these ships from shipwrecks? In this study I examine the spatial organization of ships in an effort to reconstruct the social dynamics of shipboard society.