Issues Related to Material Identification of Furniture with Boulle's Style

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lot Qty Description 1000 1 Bookcase, Six

Lot Qty Description 1000 1 Bookcase, Six Sections above Triple Cabinet, 73" tall x 57" wide x 15.5" deep (one drop down leaf front) 1001 1 Foot Stool, 12x12x12, with US Marine Corps Embroidered Stool Cover 1002 1 Hall Bench, Storage under Seat, 38.5" wide x 21" deep x 34" tall, Carved Wood 1003 1 Roll Top Desk Reproduction, with Two File Drawers, Two Storage Drawers, One Center Drawer, Four Shelves under Roll Top, and Five Slots above Roll Top, 50" wide x 22" deep x 48" tall, Brass Pulls and Handles 1004 1 Child's Rocker, Painted Black with Fruit Designs, 27" tall x 15" wide x 18" deep and Embroidered Pillow "There's No Place Like Home" 1005 1 Two Plastic Ammo Bins, Water Resistant, Holds 30 lbs., 7.5" long x 13" wide x 7.25" tall 1006 1 Plant Stand with Marble Top, Three Footed, 27" tall x 14" diameter 1007 1 Half Round Table, with Scalloped Top, Three Legs, 11" deep x 21" wide x 21" tall 1008 1 Lamp, 28" tall, with Floral Designed Silver Base and Designer Fabric Shade 1009 1 Table, 24" wide x 12" deep x 24" tall, with Decorative Brace 1010 1 Samsung 46" Diagonal TV, with Remote, Model #LN46A650A1F 1011 1 Sony HDMI CD/DVD Player, with Remote, Model #DVP-NS700H 1012 1 Oval Bookcase/TV Stand, Inlayed, 48" wide x 19" deep x 31" tall, Four Shelves 1013 1 Metal and Glass Coffee Table (matches Lot#1014), 30" deep x 49" wide x 21" tall, has Metal Shelf on Bottom 1014 1 Metal and Glass Lamp Table/End Table (matches Lot #1013), 26" wide x 26" deep x 24" tall 1015 1 Insignia 24" Diagonal TV, with Remote and RCA Interior Antenna Panel 1016 1 Leather -

Gifts of State Elementary

“We are a nation of communitis... a brilliant diversity spread like strs, like a thousand points of light in a broad and peaceful sky.” -President, George. H.W. Bush GEORGE H.W. BUSH PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY AND MUSEUM: GIFTS OF STATE ELEMENTARY OBJECTIVE: Students will analyze the gifs of state received by President George H.W. Bush. Students will conduct research about a gif of state through an artifact analysis. Research will include a mapping activity, artifact symbolism analysis, and cultural connection. TOPIC: Goals and Principles of the Unites States Constitution ELEMENTARY SOCIAL STUDIES TEKS: K.3C, K.4A, K.13A, K.14D, 1.3B,,1.5A, 1.14A, 1.16A, 1.17D, 2.3A, 2.4A, 2.12A, 2.12B, 2.15A, 2.16F, 3.3A, 3.3B, 3.4C, 3.10A, 3.10B, 3.14A, 3.14C, 3.15E, 4.19A, 4.19C, 4.21D, 5.18A, 5.20B, 5.23A, 5.23C, 5.25D Social Studies TEKS refect the NEW Streamlined TEKS that will be implemented in elementary schools in the 2020-2021 school year. 1 GIFTS OF STATE PROGRAM MATERIALS: PILLARS TO LIVE BY PASSPORT RESOURCE (page E3-E4): 1 set per student or student group EDUCATOR’S GUIDE SECURITY BRIEFING (page E5-E6): 1 set per student or student group GIFTS OF ARTIFACTS (page E7-12): 1 set per student or student group PILLAR CLOSURE SHEET (page E13): 1 per student or student group ARTIFACT ANALYSIS: (page E14): 1 per student or student group STATE THE BOTTOM LINE (page E15): 1 per student or student group ELEMENTARY PROGRAM INSTRUCTIONS: 1. -

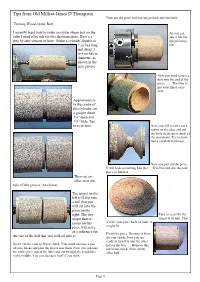

Turning Tips

Tips from Old Millrat-James D Thompson Now put the piece with the spigot back into the lathe. Turning Wood oyster Box; I recently leant how to make an oyster shape box on the As you can lathe I used silky oak for this demonstration. Here’s a see, it has the step by step version of how; Make a cylinder about 6 or spigot facing 7 inches long out. and about 3 to 4 inches in diameter. as shown in the next picture Next you need to turn a dish into the end of the piece. The time to put your finish on is now. Approximately in the centre of this cylinder cut a groove about 1/4” deep and 3/8” wide. See next picture. Next you will need to cut a radius on the edge and cut the back of the piece most of the way down. Try to main- tain a constant thickness. Now you part off the piece. It will look something like this. It will be put into the next piece to finish it. Then cut an- other near one side of this groove. As shown. The spigot on the left will slip into a bell that you will cut into the piece on the right. The tiny Turn a recess for the spigot that re- spigot to fit into. This mains on this will be your jam chuck so make it piece will serve a tight fit. as a reference for Finish the piece. Remove it from the size of the bell that you will cut into it. -

Miscellaneous Gif Ts and Personal Items

46 Russell-Hampton Company MISCELLANEOUS GIFTS www.ruh.com 1.800.877.8908 47 Miscellaneous Gifts and Personal Items A. R34533 Howard Miller Weatherton Clock Hygrometer Thermometer - Brushed Aluminum desk clock with thermometer and barometer. Price includes engraving. This item looks best with no more than 4 lines of engraving. Unit Price $67.95 • Buy 3 $63.95 • Buy 6 $59.95 • Buy 12 $55.95 B. R34597 Desk Analog Alarm Clock Quartz analog alarm clock features alarm with snooze functions, seconds hand, and 5/8" cloisonné Rotary International emblem. (Uses 1 AA battery, not included.) Unit Price $10.75 • Buy 6 $10.18 • Buy 12 $9.67 • Buy 25 $9.19 C. R34597C Personalized Analog Alarm Clock Add a personalized engraved plate with up to 4 lines of engraving to the above clock for an extra special touch on a functional gift. Unit Price $16.95 • Buy 6 $16.45 • Buy 12 $15.95 • Buy 25 $15.45 D. R34596 World Time Clock World time desk clock with alarm. Touch the buttons on the world map to select the time in 22 cities around the world. Large digital display features local time with month, day/date and temperature. (Uses 2 AA batteries, not included.) Unit Price $18.85 • Buy 3 $17.85 • Buy 6 $16.98 • Buy 12 $16.15 E. R34598 Digital Multi-Function Alarm Clock Multi-function alarm clock and calendar featuring snooze, 24 hour timer and digital thermometer. Displays month, day, date, time and temperature. Battery included. 3-1/4" x 3-1/2" x 1" Unit Price $11.95 • Buy 6 $11.35 • Buy 12 $10.75 R34598C • Custom imprint available. -

Tortoiseshell Real Or Fake?

Tortoiseshell Real or Fake? How to tell the difference This article will concentrate upon the use of tortoiseshell for ornamental hair combs, as well as the various materials which have been employed to imitate it. However much of the material included here will be of interest to collectors of other antique and vintage shell objects. I will outline some rules of thumb for distinguishing genuine from imitation tortoiseshell, and methods for caring for it. Introduction For collectors of antiques and vintage items there are many reasons why it is important to be able to distinguish real from fake (or faux) tortoiseshell. 1) Real turtle shell is not allowed on eBay. If you are a seller and you are reported by a snitch for selling items in real shell you will get your listing/s pulled and a policy violation. You could even have your account suspended. 2) Much more significant is the fact that trade in real shell violates several US and other international laws. There are different regulations for antique and modern items made from turtle shell. The legal situation is extremely complex and what is allowed in one state or country may be prohibited in another. This however, is not an area that I intend to discuss here. Further information and reference to the various laws can be found in the eBay help section dealing with prohibited items. 3) Antique items made from real shell command a far higher price than those in synthetic or other substitutes because of their rarity value. So if you are a seller or serious collector it is important for economic (as well as aesthetic) reasons to be able to distinguish it from other substances. -

MONDAY 28Th JUNE at 9Am CHINA and ORNAMENTAL ITEMS

MONDAY 28th JUNE at 9am BUYERS PREMIUM 21.60% We have limited seats for sale day which need to be prebooked CHINA AND ORNAMENTAL ITEMS 1 Three Royal Doulton figures; Summers Day HN3378, The Last Waltz HN2315 and Lynne HN2329 2 A photo frame with cresting of trumpet and flowers and jewelled inner frame 3 Three Royal Doulton figures; Top o'the Hill, Kirsty and Old Country Roses 4 A Beswick St. Bernard 5 A famille rose hand mirror, brass box et cetera 6 Three plastic jade style horses and two soapstone pieces monkeys 7 An Edwardian teapot transfer printed scene The Pavilion, Brighton 8 A set of nine brass napkin rings set semi-precious stones, another with bird design and a metal and onyx photo frame 9 Three Royal Doulton figures; Jennifer HN3447, Linda HN3374, and Fleur HN2368 10 Richard Wilson - a handpainted pottery jug 11 Two brass and enamel dishes, shagreen box, carved box and a Swiss cottage musical box 12 A Royal Doulton vase 13 A selection of oriental scent bottles et cetera 14 A Bossons wall ornament Kingfisher and another Blue Tits feeding young in bird house 15 A travelling chess set (one piece missing), cross et cetera 16 A carved elephant, figures and a bronze finish ballerina (repaired) 17 A triple folding travelling mirror frontis with picture of girl (one peg foot missing) 18 A Daum three section glass dish (slight chip to base) 19 Various printers letters and numbers in a decorative box 20 An Art Deco style lamp lady with arms in air 21 A Kaiser table lamp decorated pink flowers MASKS ARE MANDATORY IN THE SALEROOM PLEASE OBSERVE 2m GAPS AND SANITISE HANDS WHEN ENTERING THE SALEROOM AND OBSERVE SINGLE PERSON VIEWING AREAS AND ONE WAY SYSTEM. -

Stephenson's Auction General Auction

9 One lot of rugs, wooden plant stand, Stephenson’s decorative box, purses, kitchen utensils, Auction plates, board games, etc. 1005 Industrial Blvd. 10 One lot of model cars, Coors Light advertising banner, baby dolls, pool balls, Southampton, PA, 18966 etc. General Auction 11 One lot of framed artwork, lamps, Friday, September 21, 2018 figurines, etc. 4PM 12 One lot of sports cards, statues, etc. Inspection 2-4PM 13 One lot of dinnerware, wall clocks, (215) 322-6182 domed cased clock, knives, artwork, etc. www.stephensonsauction.com 14 One lot of hats, lamps, wicker baskets, sewing materials, etc. Catalog listing is for general selling order only. You are urged to inspect 15 One lot of silver plated forks, these items before bidding on them. figurines, jewelry box, picture frames, silver plated bowl, etc. 16 One lot of Legos, toys, etc. BOX LOTS 1 One lot of framed artwork, Nativity 17 One lot of linens, Ihome, etc. figurines, pottery planter, etc. 18 One lot of flatware, 3D model 2 One lot of plates, glass punch bowl puzzle, wooden candlestick, womens shoes, set, Fiestaware salt and pepper shakers, dinnerware, etc. glasswares, Ihome, etc. 19 One lot Budweiser glasses, brass 3 One lot of sports cards, etc. candlesticks, owl figurines, snow globe, silver plated candlesticks, etc. 4 One lot of a framed needlepoint, silver plated pitcher, glasswares, etc. 20 One lot of framed artwork, etc. 5 One lot of Yearbooks, paper 21 One lot of camera's, projectors, ephemera, etc. creamers, gravy boat, sports cards, etc. 6 One lot of assorted silver plated 22 One lot of marble horse head items, etc. -

The Ward Family of Deltaville Combined 28,220 Hours of Service to the Museum Over the Course of the Last St

Fall 2012 Mission Statement contents The mission of the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum is to inspire an understanding of and appreciation for the rich maritime Volunteers recognized for service heritage of the Chesapeake Bay and its tidal reaches, together with the artifacts, cultures and connections between this place and its people. Vision Statement The vision of the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum is to be the premier maritime museum for studying, exhibiting, preserving and celebrating the important history and culture of the largest estuary in the United States, the Chesapeake Bay. Sign up for our e-Newsletter and stay up-to-date on all of the news and events at the Museum. Email [email protected] to be added to our mailing list. Keep up-to-date on Facebook. facebook.com/mymaritimemuseum Follow the Museum’s progress on historic Chesapeake boat 15 9 PHOTO BY DICK COOPER 2023 2313 restoration projects and updates on the (Pictured front row, from left) George MacMillan, Don Goodliffe, Pam White, Connie Robinson, Apprentice For a Day Program. Mary Sue Traynelis, Carol Michelson, Audrey Brown, Molly Anderson, Pat Scott, Paul Ray, Paul Chesapeakeboats.blogspot.com Carroll, Mike Corliss, Ron Lesher, Cliff Stretmater, Jane Hopkinson, Sal Simoncini, Elizabeth A general education forum Simoncini, Annabel Lesher, Irene Cancio, Jim Blakely, Edna Blakely. and valuable resource of stories, links, and information for the curious of minds. FEATURES (Second row, from left) David Robinson, Ann Sweeney, Barbara Reisert, Roger Galvin, John Stumpf, 3 CHAIRMAN’S MESSAGE 12 LIFELINES 15 Bob Petizon, Angus MacInnes, Nick Green, Bill Price, Ed Thieler, Hugh Whitaker, Jerry Friedman. -

Sale Maker Auctions Lot Assignment Listing

Sale Maker Auctions www.salemakerauctions.com Lot Assignment Listing Warehouse - Estate Liquidation Auction All Sales Are Final / and are Sold "AS IS" Must Be Registered To Bid CASH Only - No Checks / Debit / Credit Cards Accepted Sales Tax Applies Buyers Premium Applies Removal is Same Day Unless Management Approves Load & Go - No sorting of items on property Auctioneer: Forrest O'Brien Ca Bond No. 00104533207 Page 1 LOT # ROOM #1 ROOM #1 BASIC DESCRIPTION LOT # ROOM #1 ROOM #1 (Cont.) BASIC DESCRIPTION 1 1st shelf - airplane / Coca-Cola figurines 57 Wooden Mini Trunks / Decorative Ceramic Plates / Decorative Wooden Utensils 2 2nd shelf - Disney items & includes Disney Studio Air Race Picture58 inCeramic Frame Coffee Cups / Ceramic Tea Pots / Silver Serving Tray 3 3rd Shelf - Coca Cola items / video camera / still shot camera &59 figurinesArtwork & jewelry - Basketball Player - Michael Jordan in Frame 4 4th Shelf - Books figurines / DVD's / Misc. Jewelry 60 3.5 - 4 ft. Tall Brown Vase 5 June Nelson Seascape Oil Painting 61 Gold Magazine Rack / Glass Ashtray / Bowl & Vase 6 Tupac & Notorious BIG picture frame 62 Black Planter Pot on Wood Stand 7 2nd shelf - jewelry / sports cards / mirror 63 Framed Artwork 8 3rd shelf - jewelry / sports cards / belts 64 Framed Artwork 9 4th shelf - jewelry / vases / vanity mirrors 65 Framed Artwork 10 5th shelf - broaches / knives / purse / picture frames 66 Framed Artwork 11 Peewee Herman Doll / Lamps / Clock / figurines 67 Framed Artwork 12 Plate / picture frame / mini trunk 68 Framed Artwork 13 Precious Moments figurines / glassware 69 Framed Artwork 14 Ceramic Ashtray / bronze figurines 70 Framed Artwork 15 Artwork - Dragon in frame 71 Framed Artwork 16 Artwork - Woman / skull 72 Framed Artwork 17 Misc. -

Short-Range Movements of Hawksbill Turtles (Eretmochelys Imbricata) from Nesting to Foraging Areas Within the Hawaiian Islands1

Short-Range Movements of Hawksbill Turtles (Eretmochelys imbricata) from Nesting to Foraging Areas within the Hawaiian Islands1 Denise M. Parker,2,3,4 George H. Balazs,3 Cheryl S. King,5 Larry Katahira,6 and William Gilmartin5 Abstract: Hawksbill sea turtles, Eretmochelys imbricata, reside around the main Hawaiian Islands but are not common. Flipper-tag recoveries and satellite track- ing of hawksbills worldwide have shown variable distances in post-nesting travel, with migrations between nesting beaches and foraging areas ranging from 35 to 2,425 km. Nine hawksbill turtles were tracked within the Hawaiian Islands using satellite telemetry. Turtles traveled distances ranging from 90 to 345 km and took between 5 to 18 days to complete the transit from nesting to foraging areas. Results of this study suggest that movements of Hawaiian hawksbills are rela- tively short-ranged, and surveys of their foraging areas should be conducted to assess status of the habitat to enhance conservation and management of these areas. Hawksbill sea turtles, Eretmochelys im- 1900s because of toxicity, but as hawksbill bricata (L.), are found in nearshore habitats numbers declined due to harvesting for scutes in tropical regions of all oceans. Hawksbill (Carrillo et al. 1999, Campbell 2003) toxicity turtles are listed as Critically Endangered in also seemed to decline. McClenachan et al. the International Union for Conservation of (2006) suggested that this reduction in toxicity Nature (IUCN) Redbook (Hilton-Taylor may be connected to the declines in hawksbill 2000) and as Endangered under the Conven- numbers because of an increased availability tion on International Trade in Endangered of less-toxic sponges on which hawksbills Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) prefer to forage. -

The Analysis of Sea Turtle and Bovid Keratin Artefacts Using Drift

Archaeometry 49, 4 (2007) 685–698 doi: 10.1111/j.1475-4754.2007.00328.x BlackwellOxford,ARCHArchaeometry0003-813X©XXXORIGINALTheE. UniversityO. analysis Espinoza, UK Publishing ofofARTICLES seaB.Oxford, W. turtle LtdBaker 2007 and and bovid C. A.keratin THEBerry artefacts ANALYSIS OF SEA TURTLE AND BOVID KERATIN ARTEFACTS USING DRIFT SPECTROSCOPY AND DISCRIMINANT ANALYSIS* E. O. ESPINOZA† and B. W. BAKER US National Fish & Wildlife Forensics Laboratory, 1490 E. Main St, Ashland, OR 97520, USA and C. A. BERRY Department of Chemistry, Southern Oregon University, 1250 Siskiyou Blvd, Ashland, OR 97520, USA We investigated the utility of diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy (DRIFTS) for the analysis and identification of sea turtle (Family Cheloniidae) and bovid (Family Bovidae) keratins, commonly used to manufacture historic artefacts. Spectral libraries are helpful in determining the class of the material (i.e., keratin versus plastics), but do not allow for inferences about the species source of keratin. Mathematical post- processing of the spectra employing discriminant analysis provided a useful statistical tool to differentiate tortoiseshell from bovid horn keratin. All keratin standards used in this study (n = 35 Bovidae; n = 24 Cheloniidae) were correctly classified with the discriminant analysis. A resulting performance index of 95.7% shows that DRIFTS, combined with discriminant analysis, is a powerful quantitative technique for distinguishing sea turtle and bovid keratins commonly encountered in museum collections and the modern wildlife trade. KEYWORDS: KERATIN, DRIFT SPECTROSCOPY, DISCRIMINANT ANALYSIS, X-RAY FLUORESCENCE, SEA TURTLE, BOVID, TORTOISESHELL, HORN, WILDLIFE FORENSICS INTRODUCTION The keratinous scutes of sea turtles and horn sheaths of bovids have been used for centuries in artefact manufacture (Aikin 1840; Ritchie 1975). -

Encino (California, USA) PARTNER MANAGED Estate Sale Online Auction - Louise Avenue

10/01/21 05:13:58 Encino (California, USA) PARTNER MANAGED Estate Sale Online Auction - Louise Avenue Auction Opens: Sat, Nov 21 5:00pm PT Auction Closes: Wed, Dec 2 7:30pm PT Lot Title Lot Title 0001 HP Printer A 0032 Rolling Metal Book Rack A 0002 Wooden Desk A 0033 Burnt Orange Retro Office Chair A 0003 Acer Laptop A 0034 Stack Of Books A 0004 Green Table Lamp A 0036 Book Lot A 0005 Computer, Monitor, Keyboard, Mouse And 0037 Metal Rolling Book Cart A Speaker A 0038 Retro Desk Items A 0006 Desk Lamp A 0039 Ronson Gold Pencil Lighter, Assorted Office 0007 Book Lot A Items A 0008 Book Lot A 0040 Telephone And Glasses A 0009 Book Lot A 0041 Mustard Retro Office Chair A 0010 Book Lot A 0042 Gold Colored Floor Lamp A 0011 Book Lot A 0043 Floral Jewelry Box A 0012 Book Lot A 0044 Book And Office Lot A 0013 Book Lot A 0045 Book Lot A 0014 Historical LIFE Magazine Lot A 0046 Wooden Book Shelf A 0015 Historical LIFE Magazines A 0047 Vintage Watch And Item Lot A 0016 Antique Piano Sheet Music A 0048 IBM Selectric II Typewriter A 0017 Tan Metal File Cabinet A 0049 Large Book Lot With Antique Bookends A 0018 Plastic Eagle Decoration A 0050 Book Lot A 0019 The Childrens Giant Atlas Of The Universe A 0051 Book Lot A 0020 Vintage Kids Books A 0052 Book Lot A 0021 Marilyn Monroe Book Lot A 0053 Book Lot A 0022 Atari Computer 600XL A 0054 Book Lot A 0023 IBM Executive Typewriter A 0055 Book Lot A 0024 Wooden End Table A 0056 Book Lot A 0025 Assorted Lot A 0057 Book Lot A 0026 Book Lot A 0058 Book Lot A 0027 Metal Chair A 0059 Book Lot A 0028 Historical