Armageddon in Retrospect

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Discourse of Redemption in Three of Kurt Vonnegut's Novels

Tutton Parker 1 What’s in the Potato Barn: A Discourse of Redemption in Three of Kurt Vonnegut’s Novels A Thesis Submitted to The Faculty of the College of Arts and Science in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts and English By Rebecca Tutton Parker April 2018 Tutton Parker 2 Liberty University College of Arts and Sciences Master of Arts in English Student Name: Rebecca Tutton Parker Thesis Chair Date First Reader Date Second Reader Date Tutton Parker 3 Table of Contents Chapter One: Introduction………………………………………………………………………...4 Chapter Two: Redemption in Slaughterhouse-Five and Bluebeard…………………………..…23 Chapter Three: Rabo Karabekian’s Path to Redemption in Breakfast of Champions…………...42 Chapter Four: How Rabo Karabekian Brings Redemption to Kurt Vonnegut…………………..54 Chapter Five: Conclusion………………………………………………………………………..72 Works Cited……………………………………………………………………………………..75 Tutton Parker 4 Chapter One: Introduction The Bluebeard folktale has been recorded since the seventeenth century with historical roots even further back in history. What is most commonly referred to as Bluebeard, however, started as a Mother Goose tale transcribed by Charles Perrault in 1697. The story is about a man with a blue beard who had many wives and told them not to go into a certain room of his castle (Hermansson ix). Inevitably when each wife was given the golden key to the room and a chance alone in the house, she would always open the door and find the dead bodies of past wives. She would then meet her own death at the hands of her husband. According to Casie Hermansson, the tale was very popular in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, which spurred many literary figures to adapt it, including James Boswell, Charles Dickens, Herman Melville, and Thomas Carlyle (x). -

The BG News April 15, 1999

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 4-15-1999 The BG News April 15, 1999 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News April 15, 1999" (1999). BG News (Student Newspaper). 6484. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/6484 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. ■" * he BG News Women rally to 'take back the night' sexual assault. istration vivors, they will be able to relate her family. By WENDY SUTO Celesta Haras/ti, a resident of buildings, rain to parts of her story, Kissinger "The more I tell my story, the The BG News BG and a W4W member, said the or shine. The said. less shame and guilt I feel," Kissinger said. "For my situa- Women (and some men) will rally is about issues that are con- keynote "When I decided to disclose tion, I'm glad I didn't tell my take to the streets tonight, pro- sidered taboo by society, such as speaker, my sexual abuse to my family, I parents right away because I claiming a public statement in an rape and incest. She has attended Kendel came out of the closet complete- think it would have been a worse attempt to "Take Back the Night" several TBTN marches at the Kissinger, a ly," Kissinger said. -

The Vulnerabilities of Developed States to Economic Cyber Warfare

Working Paper The Vulnerabilities of Developed States to Economic Cyber Warfare Paul Cornish Head, International Security Programme and Carrington Professor of International Security, Chatham House June 2011 The views expressed in this document are the sole responsibility of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of Chatham House, its staff, associates or Council. Chatham House is independent and owes no allegiance to any government or to any political body. It does not take institutional positions on policy issues. This document is issued on the understanding that if any extract is used, the author and Chatham House should be credited, preferably with the date of the publication. Working Paper: The Vulnerabilities of Developed States to Economic Cyber Warfare INTRODUCTION The central features of the ‘cybered’ world of the early 21st century are the interconnectedness of global communications, information and economic infrastructures and the dependence upon those infrastructures in order to govern, to do business or simply to live. There are a number of observations to be made of this world. First, it is still evolving. Economically developed societies are becoming ever more closely connected within themselves and with other, technologically advanced societies, and all are becoming increasingly dependent upon the rapid and reliable transmission of ideas, information and data. Second, where interconnectedness and dependency are not managed and mitigated by some form of security procedure, reversionary mode or redundancy system, then the result can only be a complex and vitally important communications system which is nevertheless vulnerable to information theft, financial electronic crime, malicious attack or infrastructure breakdown. -

The Military Guide to Armageddon • D

The Military Guide to Armageddon • D. Giamonna, T. Anderson Chosen Books, a division of Baker Publishing Group © 2021 used by permission BATTLE- TESTED STRATEGIES TO PREPARE YOUR LIFE AND SOUL FOR THE END TIMES COL. DAVID J. GIAMMONA AND TROY ANDERSON G The Military Guide to Armageddon • D. Giamonna, T. Anderson Chosen Books, a division of Baker Publishing Group © 2021 used by permission _Giammona_MilitaryGuide_ET_bb.indd 3 10/1/20 8:02 AM 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 © 2021 by David J. Giammona and Troy Anderson Published by Chosen Books 11400 Hampshire Avenue South Bloomington, Minnesota 55438 www.chosenbooks.com Chosen Books is a division of Baker Publishing Group, Grand Rapids, Michigan Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means— for example, electronic, photocopy, recording— without the prior written permission of the publisher. The only exception is brief quotations in printed reviews. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Giammona, David J., author. | Anderson, Troy (Journalist), author. Title: The military guide to Armageddon: battle-tested strategies to prepare your life and soul for the end times / Col. David J. Giammona and Troy Anderson. Description: Minneapolis, Minnesota: Chosen Books, a division of Baker Publishing Group, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references. Identifiers: LCCN 2020038021 | ISBN 9780800761943 (paperback) | ISBN 9780800762261 (casebound) | ISBN 9781493430086 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Spiritual warfare. | End of the world. | Armageddon. Classification: LCC BV4509.5 .G466 2021 | DDC 236/.9—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020038021 Unless otherwise indicated, Scripture quotations are from THE HOLY BIBLE, NEW INTERNATIONAL VERSION®, NIV® Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc.® Used by permission. -

Key Scriptures: Revelation 19:1-21 Ezekiel 38 & 39 Joel 2:1-11

God's Master Plan In Prophecy Lesson 13 – The Battle of Armageddon & 2nd Coming of Jesus Christ Key Scriptures: Revelation 19:1-21 Ezekiel 38 & 39 Joel 2:1-11 Zechariah 12-14 Introduction Rev 19:1 After these things I heard something like a loud voice of a great multitude in heaven, saying, "Hallelujah! Salvation and glory and power belong to our God; While the Wrath of God is being poured out, there was the voice of "a great multitude in heaven" praising God! This is the redeemed church which has missed the Wrath of God and was taken out of Great Tribulation. While the earth is experiencing the judgment of God without mercy, we are experiencing His goodness without judgment! Rev 19:2-3 BECAUSE HIS JUDGMENTS ARE TRUE AND RIGHTEOUS; for He has judged the great harlot who was corrupting the earth with her immorality, and HE HAS AVENGED THE BLOOD OF HIS BOND-SERVANTS ON HER." 3 And a second time they said, "Hallelujah! HER SMOKE RISES UP FOREVER AND EVER." From what is being said in these verse, it is obvious that the church will be fully aware of what is happening upon the earth during this time, yet because we are no longer viewing earth's events through the eyes of mortal flesh, we will understand that God is righteous and true in His judgments. To modern minds it may seem strange to worship and say, “hallelujah” over the fact that God is pouring out judgment, but that is because we see imperfectly now. -

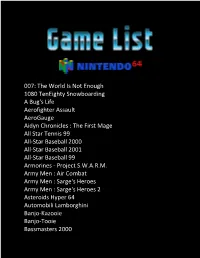

007: the World Is Not Enough 1080 Teneighty Snowboarding a Bug's

007: The World Is Not Enough 1080 TenEighty Snowboarding A Bug's Life Aerofighter Assault AeroGauge Aidyn Chronicles : The First Mage All Star Tennis 99 All-Star Baseball 2000 All-Star Baseball 2001 All-Star Baseball 99 Armorines - Project S.W.A.R.M. Army Men : Air Combat Army Men : Sarge's Heroes Army Men : Sarge's Heroes 2 Asteroids Hyper 64 Automobili Lamborghini Banjo-Kazooie Banjo-Tooie Bassmasters 2000 Batman Beyond : Return of the Joker BattleTanx BattleTanx - Global Assault Battlezone : Rise of the Black Dogs Beetle Adventure Racing! Big Mountain 2000 Bio F.R.E.A.K.S. Blast Corps Blues Brothers 2000 Body Harvest Bomberman 64 Bomberman 64 : The Second Attack! Bomberman Hero Bottom of the 9th Brunswick Circuit Pro Bowling Buck Bumble Bust-A-Move '99 Bust-A-Move 2: Arcade Edition California Speed Carmageddon 64 Castlevania Castlevania : Legacy of Darkness Chameleon Twist Chameleon Twist 2 Charlie Blast's Territory Chopper Attack Clay Fighter : Sculptor's Cut Clay Fighter 63 1-3 Command & Conquer Conker's Bad Fur Day Cruis'n Exotica Cruis'n USA Cruis'n World CyberTiger Daikatana Dark Rift Deadly Arts Destruction Derby 64 Diddy Kong Racing Donald Duck : Goin' Qu@ckers*! Donkey Kong 64 Doom 64 Dr. Mario 64 Dual Heroes Duck Dodgers Starring Daffy Duck Duke Nukem : Zero Hour Duke Nukem 64 Earthworm Jim 3D ECW Hardcore Revolution Elmo's Letter Adventure Elmo's Number Journey Excitebike 64 Extreme-G Extreme-G 2 F-1 World Grand Prix F-Zero X F1 Pole Position 64 FIFA 99 FIFA Soccer 64 FIFA: Road to World Cup 98 Fighter Destiny 2 Fighters -

Leverage and Asset Bubbles: Averting Armageddon with Chapter 11?*

The Economic Journal, 120 (May), 500–518. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0297.2010.02357.x. Ó The Author(s). Journal compilation Ó Royal Economic Society 2010. Published by Blackwell Publishing, 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK and 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148, USA. LEVERAGE AND ASSET BUBBLES: AVERTING ARMAGEDDON WITH CHAPTER 11?* Marcus Miller and Joseph Stiglitz An iconic model with high leverage and overvalued collateral assets is used to illustrate the ampli- fication mechanism driving asset prices to ÔovershootÕ equilibrium when an asset bubble bursts – threatening widespread insolvency and what Richard Koo calls a Ôbalance sheet recessionÕ. Besides interest rates cuts, asset purchases and capital restructuring are key to crisis resolution. The usual bankruptcy procedures for doing this fail to internalise the price effects of asset Ôfire-salesÕ to pay down debts, however. We discuss how official intervention in the form of ÔsuperÕ Chapter 11 actions can help prevent asset price correction causing widespread economic disruption. There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy. Hamlet From 2007 to 2009 a chain of events, beginning with unexpected losses in the US sub-prime mortgage market, was destined to bring the global financial system close to collapse and to drag the world economy into recession. ÔOne of the key challenges posed by this crisisÕ, says Williamson (2009), Ôis to understand how such major consequences can flow from such a seemingly minor eventÕ. Before describing an amplification mechanism involving overpriced assets and excessive leverage, we begin by looking, albeit briefly, at what the current macroeconomic paradigm may have to say. -

Open HONORS FINAL.Pdf

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER’S HONORS COLLEGE DIVISION OF ARTS AND HUMANITIES MENTAL ILLNESS IN FAMILY MEMOIRS: AN INTERDISCIPLINARY STUDY EXAMINING THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN MENTALLY ILL PARENTS AND THEIR CHILDREN BRANDON CHERRY SPRING 2016 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in English with honors in Letters, Arts, and Sciences Reviewed and approved* by the following: Ellen Knodt Professor of English Thesis Supervisor Karen Weekes Associate Professor of English and Women’s Studies Faculty Reader *Signatures are on file in the Schreyer’s Honors College. i Abstract This project explores the relationship between mentally ill parents and their children in the memoir form. These family memoirs offer insights into the effects of mentally ill parents on their children. The family memoirs of three famous twentieth century writers are studied to analyze the effects of mental illness in the written form, because a wide majority of the population does not have the privilege or skills to write about events effectively. Further psychological research also demonstrates how the coping mechanisms that children of mentally ill parents employ impact their development into adult life. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract………………………………………………….i Acknowledgements……………………………………..iii Introduction……………………………………………....1 i. Memoirs and Authors……………………………1 ii. Background of Mental Illnesses………………...6 iii. Link Between creativity and mental Illness.........8 The Hemingway Family: Strange Tribe……………………12 The Styron Family: Darkness Visible and Reading my Father ………………………………………21 The Vonnegut Family: The Eden Express and Just Like Someone Without Mental Illness Only More So…………………………………………………………26 Conclusion………………………………………………..36 Bibliography………………………………………………38 Academic Vita…………………………………………….41 iii Acknowledgements Thank you to Dr. -

From Voodoo to Viruses: the Evolution of the Zombie in Twentieth Century Popular Culture

From Voodoo to Viruses: The Evolution of the Zombie in Twentieth Century Popular Culture By Margaret Twohy Adviser: Dr. Bernice Murphy A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the Degree of Master’s of Philosophy in Popular Literature Trinity College Dublin Dublin, Ireland October 2008 2 Abstract The purpose of this thesis is to explore the evolutionary path the zombie has followed in 20th Century popular culture. Additionally, this thesis will examine the defining characteristics of the zombie as they have changed through its history. Over the course of the last century and edging into the 21st Century, the zombie has grown in popularity in film, videogames, and more recently in novels. The zombie genre has become a self-inspiring force in pop culture media today. Films inspired a number of videogames, which in turn, supplied the film industry with a resurgence of inspirations and ideas. Combined, these media have brought the zombie to a position of greater prominence in popular literature. Additionally, within the growing zombie culture today there is an over-arcing viral theme associated with the zombie. In many films, games, and novels there is a viral cause for a zombie outbreak. Meanwhile, the growing popularity of zombies and its widening reach throughout popular culture makes the genre somewhat viral-like as well. Filmmakers, authors and game designers are all gathering ideas from one another causing the some amount of self- cannibalisation within the genre. 3 Table of Contents Introduction 4 Chapter One 7 Evolution of the Dead Chapter Two 21 Contaminants, Viruses, and Possessions—Oh my! Chapter Three 34 Dawn of the (Digital) Dead Chapter Four 45 Rise of the Literary Zombie Conclusion 58 Bibliography 61 4 Introduction There are perhaps few, if any fictional monsters that can rival the versatility of the humble zombie (or zombi)1. -

“I Can't Sell Nails”

“I Can’t Sell Nails” Paper Presented to the Indianapolis Literary Club James A. Glass May 5, 2014 I first met Irma Vonnegut Lindener at a luncheon in the Athenaeum arranged by her younger cousin, Catherine Glossbrenner Rasmussen.1 The year was 1976, and I had met “Catey,” as Mrs. Rasmussen liked to be called, through a historic preservation project that my office, the Indianapolis Historic Preservation Commission, was conducting with the Junior League of Indianapolis. Under the persuasive influence of Reid Williamson, the new Executive Director of Historic Landmarks Foundation of Indiana, the League had adopted historic preservation as a service area for its volunteers. One of its first projects was nominating the Old Northside neighborhood for listing in the National Register of Historic Places. The project would entail considerable historical research. We decided that one way of gathering valuable information would be to conduct oral history interviews with some of the women who had grown up in the Old Northside area during its time of initial prosperity during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. When Catey heard about the project, she contacted me, then a 24-year old staff historian, about her interest in family history and in the preservation of some of the family homes in the Old Northside. That led to the luncheon at the Athenaeum with Mrs. Lindener, whom Catey called “Aunt Irma.” Aunt Irma turned out to be the daughter and only living child of Bernard Vonnegut, one of the most prominent and gifted architects in Indianapolis at the turn of the 20th century. -

The Omen Iv Armageddon 2000

The omen iv armageddon 2000 Omen IV: Armageddon is a novel published by Gordon McGill. It is a sequel to The Final Conflict, and is completely unconnected to the film, Omen IV: The Awakening. "Damien Thorn, spawn of Satan, was dead, slain by one of the sacred daggers of Armageddon. First published back in September of , Gordon McGill's novel 'Omen IV: Armageddon ' formed the fourth instalment into the Omen series, concluding. Armageddon has ratings and 11 reviews. Matt said: An enjoyable slice of 80s occult hokum that picks up exactly where The Final Conflict left o. Omen IV: Armageddon [Gordon McGill] on *FREE* shipping on qualifying offers. Omen IV: Armageddon But The Omen didn't just spawn Damien, the Antichrist. In , McGill returned to write Omen IV: Armageddon which opens with a. The Omen is a British-American horror film franchise beginning in The story was In the fourth and final film of the original series, Omen IV: The Awakening, it is revealed that . Gordon McGill; Omen IV: Armageddon , written in by Gordon McGill; Omen V: The Abomination, written in by Gordon McGill Television series: The Omen (); Damien. Going even farther, sequel novels were actually published in the (The Omen IV: Armageddon ) and (The Omen V: The. I've recently flown through Omen IV: Armageddon - wonderful pulp fun. The story as before - Ambassador To The Court Of St James has. Omen IV: Armageddon , McGill's novel, takes the loophole of The Final Conflict – Damien buggering Kate Reynolds rather than allowing. Damien's son, unwittingly raised by Paul Buher, the head of a huge international corporation, threatens to destroy the world with his demonic powers. -

Pro Wrestling Over -Sell

TTHHEE PPRROO WWRREESSTTLLIINNGG OOVVEERR--SSEELLLL™ a newsletter for those who want more Issue #1 Monthly Pro Wrestling Editorials & Analysis April 2011 For the 27th time... An in-depth look at WrestleMania XXVII Monthly Top of the card Underscore It's that time of year when we anything is responsible for getting Eddie Edwards captures ROH World begin to talk about the forthcoming WrestleMania past one million buys, WrestleMania, an event that is never it's going to be a combination of Tile in a shocker─ the story that makes the short of talking points. We speculate things. Maybe it'll be the appearances title change significant where it will rank on a long, storied list of stars from the Attitude Era of of highs and lows. We wonder what will wrestling mixed in with the newly Shocking, unexpected surprises seem happen on the show itself and gossip established stars that generate the to come few and far between, especially in the about our own ideas and theories. The need to see the pay-per-view. Perhaps year 2011. One of those moments happened on road to WreslteMania 27 has been a that selling point is the man that lit March 19 in the Manhattan Center of New York bumpy one filled with both anticipation the WrestleMania fire, The Rock. City. Eddie Edwards became the fifteenth Ring and discontent, elements that make the ─ So what match should go on of Honor World Champion after defeating April 3 spectacular in Atlanta one of the last? Oddly enough, that's a question Roderick Strong in what was described as an more newsworthy stories of the year.