Sound Mirrors: Brian Eno & Touchscreen Generative Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Live-Electronic Music

live-Electronic Music GORDON MUMMA This b()oll br.gills (lnd (')uis with (1/1 flnO/wt o/Ihe s/u:CIIlflli01I$, It:clmulogira{ i,m(I1M/;OIn, find oC('(uimwf bold ;lIslJiraliml Iltll/ mm"k Ihe his lory 0/ ciec/muir 111111';(", 8u/ the oIJt:ninf!, mui dosing dlll/J/er.f IIr/! in {art t/l' l)I dilfcl'CIIt ltiJ'ton'es. 0110 Luerd ng looks UfI("/,- 1,'ulIl Ihr vll l/laga poillt of a mnn who J/(u pel'smlfl.lly tui(I/I'sscd lite 1)Inl'ch 0/ t:lcrh'Ollic tccJlIlulogy {mm II lmilll lIellr i/s beg-ilmings; he is (I fl'ndj/l(lnnlly .~{'hooletJ cOml)fJj~l' whQ Iws g/"lulll/llly (lb!Jfll'ued demenls of tlli ~ iedmoiQI!J' ;11(0 1111 a/rc(uiy-/orllleti sCI al COlli· plJSifion(l/ allillldes IInti .rki{l$. Pm' GarrlOll M umma, (m fllr. other IWfI((, dec lroll;c lerllll%gy has fllw/lys hetl! pre.telll, f'/ c objeci of 01/ fl/)sm'uillg rlln'osily (mrl inUre.fI. lu n MmSI; M 1I11111W'S Idslur)l resltllle! ",here [ . IIt:1lillg'S /(.;lIve,( nff, 1',,( lIm;lI i11g Ihe dCTleiojJlm!lIls ill dec/m1/ ;,. IIII/sir br/MI' 19j(), 1101 ~'/J IIIlIrli liS exlell siom Of $/ili em'fier lec1m%gicni p,"uedcnh b111, mOw,-, as (upcclS of lite eCQllol/lic lind soci(ll Irislm)' of the /.!I1riotl, F rom litis vh:wJ}f)il1/ Ite ('on,~i d ".r.f lHU'iQII.f kint/s of [i"t! fu! r/urmrl1lcI' wilh e/cclnmic medifl; sl/)""m;ys L'oilabomlive 1>t:rformrl1lce groU/JS (Illd speril/f "heme,f" of cIIgilli:C'-;lIg: IUltl ex/,/orcs in dt:lllil fill: in/tulmet: 14 Ihe new If'dllllJiolO' 011 pop, 10/1(, rock, nllrl jllu /Ill/SIC llJi inJlnwu:lI/s m'c modified //till Ille recording studio maltel' -

JON HASSELL/FARAFINA Flash of the Spirit

DESCRIPTION Tak:Til/Glitterbeat present the first ever reissue and remastering of Jon Hassell and Farafina 's prescient, "Fourth World" masterwork, Flash of the Spirit , originally released in 1988. Propulsive Burkinese rhythms meet revelatory, ambient soundscapes. Co-produced with the legendary studio team of Brian Eno and Dainel Lanois . Composer and trumpeter Jon Hassell has been an elusive, iconic musical figure for more than half a century. He's best known as the pioneer and propagandist of "Fourth World" music, mixing technology with the tradition and spirituality of non-western cultures. In 1987 he joined with Farafina, the acclaimed percussion, voice, and dance troupe from Burkina Faso, to record Flash of the Spirit . While the album is a natural extension of those "Fourth World" ideas, and a new strand of Possible Musics, it also a distinctive outlier in the careers of both artists; an unrepeated merging of sounds whose influence still reverberates today. The eight members of the band -- who had also collaborated with the Rolling Stones and Ryuichi Sakamoto -- brought their long apprenticed, virtuosic drumming, and melodic textures (balafon, flute, voices) to the sessions. They built up layers and patterns of rhythm, while producers Brian Eno and Daniel Lanois (fresh off the success of U2 's Joshua Tree ) created a sonic atmosphere in which they could creatively intertwine with Hassell's digitally processed trumpet and keyboards. Despite their initial skepticism, the musicians from Farafina ended up relishing their interaction with the studio team and the trumpeter/conceptualist Hassell. The music that emerged was rich and groundbreaking, a move to transcend the boundaries between jazz, avant-garde classical, ambient and the deep rhythmic tradition embodied by Farafina. -

Acdsee Proprint

BULK RATE U.S. POSTAGE PAID Permit N9.2419 lPE lPITClHl K.C., Mo. FREE ALL THE MUSE TI:AT FITS THE PITCH ISSUE NO. 10 JULY -AUGUST 1981 LeRoi, John CaIe, Stones, Blues, 3 Friends, Musso. Give the gift of music. OIfCharlie Parleer + PAGE 2 THE PENN:Y PITCH mJTU:li:~u-:~u"nU:lmmr;unmmmrnmmrnmmnunrnnlmnunPlIiunnunr'mlnll1urunnllmn broke. Their studio is above the Tomorrow studio. In conclusion, I l;'lish Wendy luck, because l~l~ lPIITC~1 I don't believe in legislating morals. Peace, love, dope, is from the Sex Machine a.k.a. (Dean, Dean) p.S. Put some more records in the $4.49 RELIGIOUS NAPOLEON group! 4128 BROADWAY KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI 64111 Dear Warren: (Dear Sex Machine: Titles are being added to (816) 561-1580 I recently came across something the $4.49 list each month. And at the Moon I thought you might "Religion light Madness Sale (July 17), these records is excellent stuff keeping common will be $3.99! Also, it's good to learn that people quiet." --Napoleon Bonaparte the spirit of t_he late Chet Huntley still can Editor ..............• Charles Chance, Jr. (1769-1821). Keep up the good work. cup of coffee, even one vibrated Assistant Editors ...•. Rev. Frizzell Howard Drake Jay '"lctHUO':V_L,LJLe Canyon, Texas LOVE FINDS LeROI Contributing Writers and Illustrators: (Dear Mr. Drake: I think Warren would Dear Warren: Milton Morris, Sid Musso, DaVINK, Julia join us in saying, "Religion is like This is really a letter to Donk, Richard Van Cleave, Jim poultry-- you gotta pluck it and fry it LeRoi. -

The History of Rock Music: 1970-1975

The History of Rock Music: 1970-1975 History of Rock Music | 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-75 | 1976-89 | The early 1990s | The late 1990s | The 2000s | Alpha index Musicians of 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-76 | 1977-89 | 1990s in the US | 1990s outside the US | 2000s Back to the main Music page Inquire about purchasing the book (Copyright © 2009 Piero Scaruffi) Sound 1973-78 (These are excerpts from my book "A History of Rock and Dance Music") Borderline 1974-78 TM, ®, Copyright © 2005 Piero Scaruffi All rights reserved. In the second half of the 1970s, Brian Eno, Larry Fast, Mickey Hart, Stomu Yamashta and many other musicians blurred the lines between rock and avantgarde. Brian Eno (34), ex-keyboardist for Roxy Music, changed the course of rock music at least three times. The experiment of fusing pop and electronics on Taking Tiger Mountain By Strategy (sep 1974 - nov 1974) changed the very notion of what a "pop song" is. Eno took cheap melodies (the kind that are used at the music-hall, on television commercials, by nursery rhymes) and added a strong rhythmic base and counterpoint of synthesizer. The result was similar to the novelty numbers and the "bubblegum" music of the early 1960s, but it had the charisma of sheer post-modernist genius. Eno had invented meta-pop music: avantgarde music that employs elements of pop music. He continued the experiment on Another Green World (aug 1975 - sep 1975), but then changed its perspective on Before And After Science (? 1977 - dec 1977). Here Eno's catchy ditties acquired a sinister quality. -

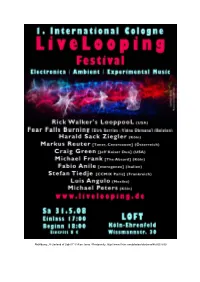

Informationen Als

Abbildung: „A Garland of Light II“ © Alan Jaras / Reciprocity, http://www.flickr.com/photos/alanjaras/465037590 Pressemitteilung 1. Internationales Kölner LiveLooping - Festival 31. Mai 2008 im LOFT (Köln), Eintritt 8 Euro, Einlaß 17 Uhr, Beginn 18 Uhr Kontakt und Information: Michael Peters, [email protected], Tel. 02207-912144 Was ist denn „Livelooping“? Livelooping-Musiker sind meist Solo-Musiker, die digitale Loop-Geräte (im Prinzip Echogeräte mit u.U. sehr langer Laufzeit) benutzen, um sich selbst in Echtzeit zu „multiplizieren“, d.h. die live erzeugten Klänge zu wiederholen und zu komplexen Klangschichten aufzutürmen. Das können rhythmische Gebilde sein, aber auch dichte Wolken von Ambient-Klängen. Auch ganze Songstrukturen können live mit Loops aufgebaut und dann als Grundlage für Soli benutzt werden. Der erste Livelooper (damals noch mit Hilfe von Tonbandgeräten = Tape Loops) war der amerikanische Minimalist Terry Riley, der in den späten 60ern mit seinem psychedelischen Loop- Stück „A Rainbow in Curved Air“ und nächtelangen loop-basierten „All Night Flights“ weltbekannt wurde. Später brachte der Ambient-Musik-Erfinder Brian Eno, dessen erstes Ambient-Werk "Discreet Music" mit Tape Loops realisiert wurde, dem King-Crimson-Gitarristen Robert Fripp diese Technik bei. Fripp erzeugte dann in den späten 70ern mit seiner elektrischen Gitarre und seinem „Frippertronics“- Tonbandsystem ungewöhnliche Klanggebilde und machte die Möglichkeiten des Livelooping vor allem Gitarristen bewußt, die nach neuen musikalischen Wegen suchten. Seit den 80ern kann Livelooping mit Hilfe von analogen, später digitalen Loop-Delays erzeugt werden; es gibt mittlerweile eine reichhaltige Auswahl an einfachen und komplexen Loop-Geräten sowie an Software für das Livelooping aus dem Computer. Eine wachsende weltweite Community von Loop-Musikern diskutiert seit über 10 Jahren die technischen und musikalischen Aspekte des Livelooping auf der Loopers Delight-Internet-Mailingliste, und in Amerika, Europa und Japan finden regelmäßig Festivals für Loop-basierte Musik statt. -

Drone Music from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Drone music From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Drone music Stylistic origins Indian classical music Experimental music[1] Minimalist music[2] 1960s experimental rock[3] Typical instruments Electronic musical instruments,guitars, string instruments, electronic postproduction equipment Mainstream popularity Low, mainly in ambient, metaland electronic music fanbases Fusion genres Drone metal (alias Drone doom) Drone music is a minimalist musical style[2] that emphasizes the use of sustained or repeated sounds, notes, or tone-clusters – called drones. It is typically characterized by lengthy audio programs with relatively slight harmonic variations throughout each piece compared to other musics. La Monte Young, one of its 1960s originators, defined it in 2000 as "the sustained tone branch of minimalism".[4] Drone music[5][6] is also known as drone-based music,[7] drone ambient[8] or ambient drone,[9] dronescape[10] or the modern alias dronology,[11] and often simply as drone. Explorers of drone music since the 1960s have included Theater of Eternal Music (aka The Dream Syndicate: La Monte Young, Marian Zazeela, Tony Conrad, Angus Maclise, John Cale, et al.), Charlemagne Palestine, Eliane Radigue, Philip Glass, Kraftwerk, Klaus Schulze, Tangerine Dream, Sonic Youth,Band of Susans, The Velvet Underground, Robert Fripp & Brian Eno, Steven Wilson, Phill Niblock, Michael Waller, David First, Kyle Bobby Dunn, Robert Rich, Steve Roach, Earth, Rhys Chatham, Coil, If Thousands, John Cage, Labradford, Lawrence Chandler, Stars of the Lid, Lattice, -

The Infinisphere: Expanding Existing Electroacoustic Sound Principles by Means of an Original Design Application Specifically for Trombone

THE INFINISPHERE: EXPANDING EXISTING ELECTROACOUSTIC SOUND PRINCIPLES BY MEANS OF AN ORIGINAL DESIGN APPLICATION SPECIFICALLY FOR TROMBONE BY JUSTIN PALMER MCADARA SCHOLARLY ESSAY Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music with a concentration in Jazz Performance in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2020 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor James Pugh, Chair and Director of Research Assistant Professor Eli Fieldsteel Professor Erik Lund Professor Charles McNeill DMA Option 2 Thesis and Option 3 Scholarly Essay DEPOSIT COVERSHEET University of Illinois Music and Performing Arts Library Date: July 10, 2020 DMA Option (circle): 2 [thesis] or 3 [scholarly essay] Your full name: Justin Palmer McAdara Full title of Thesis or Essay: The InfiniSphere: Expanding Existing Electroacoustic Sound Principles by Means of an Original Design Application Specifically for Trombone Keywords (4-8 recommended) Please supply a minimum of 4 keywords. Keywords are broad terms that relate to your thesis and allow readers to find your work through search engines. When choosing keywords consider: composer names, performers, composition names, instruments, era of study (Baroque, Classical, Romantic, etc.), theory, analysis. You can use important words from the title of your paper or abstract, but use additional terms as needed. 1. Trombone 2. Electroacoustic 3. Electro-acoustic 4. Electric Trombone 5. Sound Sculpture 6. InfiniSphere 7. Effects 8. Electronic If you need help constructing your keywords, please contact Dr. Bashford, Director of Graduate Studies. Information about your advisors, department, and your abstract will be taken from the thesis/essay and the departmental coversheet. -

2Ser Australia Jan 09

The Spice of Life - 2/2/09 2:37 AM PROGRAMS WHAT'S ON SUPPORT US ABOUT US CONTACT US The Spice of Life Tuesday 1:30pm - 3:00pm Saturday 6:00pm - 7:30pm The Spice of Life with Hans Stoeve Today's show 27 January 2009 Amrhan An Ba / The Honest Bar- Michael Goldrick- CD Wired The New Post Office- Dennis Cahill & Martin Hayes- CD Welcome Here Again Baile Mhuirne- Iarla O'Lionaird- Music At Matt Malloys Kilkelly- Pat & Becky Egan- CD Music At Matt Malloys As Christy Roved Out / The KildaremansFactory- Planxty- Live 2004 Punjab- Karunesh- Global Spirit Tributo a Dorival- Baden Powell- Live at The Rio Jazz Club David Sylvian- Nine Horses 20 January 2009 Sandhya- Amjad Ali Khan- CD Moksha Yarimo / Ne Yalan Soyleyeyim- Duoud- CD Wild Serenade Black Temple- Steve Tibbetts- CD A Man About A Horse Obama / Dagna- Fula Flute- CD Mansa America (www.fulaflute.net) Poye / Ahe Sira Bila- Issa Bagayogo- CD Mali Koura (www.sixdegreesrecords.com) Roger Richards of Extreme Records talking about Robert Vincs Saraghina / Avatar- Robert Vincs- CD Vedic Kingdom Tion- Nils Peter Molvaer= CD Khmer Gula Gula remixed by Chilluminati- CD Mari Boine Remixed (Jazzland) Cuovgi Liekkas remixed by Jah Wobble-CD Mari Boine Remixed Revolution Blues- Neil Young- CD On The Beach 13 January 2009 Kim Cunio- Song for Dora- CD Infloressence Nitin Sawhney- Breathing Light- CD Prophesy Nitin Sawhney- Beyond Skin- CD Beyond Skin Jimmy Little- Into temptation- CD Messenger Chris Meyer- Dervish- CD Lucid Dreams Jah Wobble- I Love Everybody- CD Take Me To God Lloyd Cole- Big Snake- CD -

WHAT USE IS MUSIC in an OCEAN of SOUND? Towards an Object-Orientated Arts Practice

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Oxford Brookes University: RADAR WHAT USE IS MUSIC IN AN OCEAN OF SOUND? Towards an object-orientated arts practice AUSTIN SHERLAW-JOHNSON OXFORD BROOKES UNIVERSITY Submitted for PhD DECEMBER 2016 Contents Declaration 5 Abstract 7 Preface 9 1 Running South in as Straight a Line as Possible 12 2.1 Running is Better than Walking 18 2.2 What You See Is What You Get 22 3 Filling (and Emptying) Musical Spaces 28 4.1 On the Superficial Reading of Art Objects 36 4.2 Exhibiting Boxes 40 5 Making Sounds Happen is More Important than Careful Listening 48 6.1 Little or No Input 59 6.2 What Use is Art if it is No Different from Life? 63 7 A Short Ride in a Fast Machine 72 Conclusion 79 Chronological List of Selected Works 82 Bibliography 84 Picture Credits 91 Declaration I declare that the work contained in this thesis has not been submitted for any other award and that it is all my own work. Name: Austin Sherlaw-Johnson Signature: Date: 23/01/18 Abstract What Use is Music in an Ocean of Sound? is a reflective statement upon a body of artistic work created over approximately five years. This work, which I will refer to as "object- orientated", was specifically carried out to find out how I might fill artistic spaces with art objects that do not rely upon expanded notions of art or music nor upon explanations as to their meaning undertaken after the fact of the moment of encounter with them. -

The Philip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966-1976 David Allen Chapman Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) Spring 4-27-2013 Collaboration, Presence, and Community: The Philip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966-1976 David Allen Chapman Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Chapman, David Allen, "Collaboration, Presence, and Community: The hiP lip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966-1976" (2013). All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). 1098. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/1098 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of Music Dissertation Examination Committee: Peter Schmelz, Chair Patrick Burke Pannill Camp Mary-Jean Cowell Craig Monson Paul Steinbeck Collaboration, Presence, and Community: The Philip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966–1976 by David Allen Chapman, Jr. A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2013 St. Louis, Missouri © Copyright 2013 by David Allen Chapman, Jr. All rights reserved. CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES .................................................................................................................... -

Icebreaker: Apollo

Icebreaker: Apollo Start time: 7.30pm Running time: 2 hours 20 minutes with interval Please note all timings are approximate and subject to change Martin Aston looks into the history behind Apollo alongside other works being performed by eclectic ground -breaking composers. When man first stepped on the moon, on July 20th, 1969, ‘ambient music’ had not been invented. The genre got its name from Brian Eno after he’d released the album Discreet Music in 1975, alluding to a sound ‘actively listened to with attention or as easily ignored, depending on the choice of the listener,’ and which existed on the, ‘cusp between melody and texture.’ One small step, then, for the categorisation of music, and one giant leap for Eno’s profile, which he expanded over a series of albums (and production work) both song-based and ambient. In 1989, assisted by his younger brother Roger (on piano) and Canadian producer Daniel Lanois, Eno provided the soundtrack for Al Reinert’s documentary Apollo: the trio’s exquisitely drifting, beatific sound profoundly captured the mood of deep space, the suspension of gravity and the depth of tranquillity and awe that NASA’s astronauts experienced in the missions that led to Apollo 11’s Neil Armstrong taking that first step on the lunar surface. ‘One memorable image in the film was a bright white-blue moon, and as the rocket approached, it got much darker, and you realised the moon was above you,’ recalls Roger Eno. ‘That feeling of immensity was a gift: you just had to accentuate the majesty.’ In 2009, to celebrate the 40th anniversary of that epochal trip, Tim Boon, head of research at the Science Museum in London, conceived the idea of a live soundtrack of Apollo to accompany Reinert’s film (which had been re-released in 1989 in a re-edited form, and retitled For All Mankind. -

Perth Amboy, NJ

-■ "m· l> SOUTH AMBOY. I W00PBBID6E. | PLEASANT PLAINS. T0TTENV1LLE. Hay'aHaii*M M m M I GET IN THK CONTEST. For Tou cannot afford to miss that vacation trip to Niagara Falls this LOCAL MEN TO Health DOG CATCHER the Summer's summer. Staten Island Is to be rep- ARREST TWO resented regardless of how the Never Falls to others stand. Pleasant Plains can RESTORE GRAY or FADED Cooking send one of her fair daughters if the ENCAMPMENT 18 APPOINTED No kitchen people get together and hustle. Qet FOR BURGLARY HAIR to Its NATURAL appliance give» In the contest noyr. Save the cou- •uch actual satisfaction and and secure a new or COLOR and BEAUTY pons subscriber real home as the New two. It is an to a de- Several Members of Truex Post Committee comfort easy way get Youths Held on ot No matter how long it has been gray Woodbridge Township Perfection Wick Blue Flame lightful outing. Remember, all ex- 'uspicion Will Attend or faded. Promotes a luxuriant growth Takes Action to End Scare- Cook-Stove. penses are paid. Think It over. Srm ' G.A.R. Session of healthy hair. Stops ite falling out, Pil Knowing ing aï Hotel and removes Dan- £ Kitchen work, thi» coming w BIRTHDAY at Park. positively Commends Health Board. ^ ANNIVERSARY. Theft at [ reischa / Asbury druff. Keeps hair soft and glossy. Re- summer, will be better and quicker done, with greater Gladys Englebrecht entertained lie. fuse all substitutes. 2)i times as much comfort for the worker if, instead of the stifling friends at a birthday party at her in |1.00 as 50c size.