Introduction to Fracture Mechanics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Engineering Ethics – a Review

Erik Jonsson School of Engggineering and The Un ivers ity o f Texas a t Da llas Computer Science Engineering Ethics – A Review • Engineers are professional practitioners (in the same way that lawyers and physicians are professionals) . • Although engineers may work for companies, non- profit organizations, or governmental units, many engineers, like MD’ s or a ttorneys, are in depen den t business people and work for clients. • All professions have guidelines for interacting with clients. • We as (electrical) engineers, have ethical guidelines as well, and we often refer to them as engineering ethics . 1 EE 1202 Lecture #3 – Ethics and Technical Competence © N. B. Dodge 03/12 Erik Jonsson School of Engggineering and The Un ivers ity o f Texas a t Da llas Computer Science Interaction Rules • Society has rules of conduct that govern personal and organizational interactions. • There are various levels of these rules or behavioral guidelines. For example: – Etiquette – Rules governing personal interaction; in general, the only penalty for breaking such rules is embarrassment. – Laws – Societal mandates of behavior, with consequent penalties for breaking those rules. – Morals – Principles or standards of behavior. In general, apply to the more serious behavioral issues in a society. 2 EE 1202 Lecture #3 – Ethics and Technical Competence © N. B. Dodge 03/12 Erik Jonsson School of Engggineering and The Un ivers ity o f Texas a t Da llas Computer Science Examples • Etiquette – Proper etiquette generally involves “proper” public behavior (which can vary with the society to which the etiquette applies): Dressing professionally, speaking well (face-to-face and over the telephone), and using proper table manners. -

WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER, 2 Chair

WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER, 2 finely-ground lenses of the sociology of work as developed by Anselm Strauss and refined by Leigh Star (1991:265) who wrote: 001. Publication Committee Meeting "Work is the link between the visible and the invisible." I focus 1:00 to 3:00 pm on three forms anticipation work which are often, though not Crowne Plaza: Savoy always, invisibled/deleted. First is abduction, the feedback loopings from empirical elements to conceptualizations of them 002. 4S Council Meeting through which we produce and perform anticipation, tracing 3:00 to 6:00 pm some of its roots in pragmatist philosophy and how guessing is Crowne Plaza: Savoy work. I then extend the process(es) of simplification as analyzed by Leigh Star (1983) vis-a-vis scientific work as a key process of 003. Welcome and Opening Remarks anticipation in largely non-scientific spaces and places. I discuss 6:15 to 6:30 pm how various kinds of work "disappear" through simplifying Crowne Plaza: Grand Ballroom - East strategies, noting the loss of complexities, and the shifting An overview of 4S conference 2011. politics of responsibility for doing anticipatory labor. Last, I Chair: touch on hope, attempting to specify how it threads itself into possible futures in relation to anticipation as fuel, as energy Roli Varma, University of New Mexico source, as drive, as process, as product. In conclusion, I discuss 004. Opening Plenary: The Intellectual Legacies of Susan Leigh the shifting politics of responsibility for doing anticipatory labor, Star especially in relation to its visibility. Who does it? Under what 6:30 to 7:30 pm conditions? With what kinds of recognition or invisibling? Why Crowne Plaza: Grand Ballroom - East might it matter when anticipatory labor is commonly invisible? Susan Leigh Star (1954–2010) Mapping the Body across Diverse Information Systems: Shadow Bodies and They Make Us Human. -

Schnebele Gmu 0883E 10495.Pdf

Fusion of Remote Sensing and Non-authoritative Data for Flood Disaster and Transportation Infrastructure Assessment A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at George Mason University By Emily K. Schnebele Master of Arts University of Maryland at College Park, 1994 Bachelor of Science University of Maryland at College Park, 1992 Director: Dr. Guido Cervone, Associate Professor Department of Geography and GeoInformation Science Fall Semester 2013 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Copyright c 2013 by Emily K. Schnebele All Rights Reserved ii Acknowledgments Although I am listed as the solitary author of this work, its completion would not have been possible without the insight, guidance, and encouragement from my advisor, Dr. Guido Cervone. I have been privileged to have such a talented scientist and researcher as my advisor and mentor. No matter how challenging the task, from technical help to moral support, he always came to my aid. I have truly enjoyed being his student and I am eternally grateful for everything he has done for me. I also would like to thank the members of my committee, Dr. Nigel Waters, Dr. Richard Medina, and Dr. Monica Gentili. I have been extremely fortunate to have a committee who cares so much about me and my work. Without fail, they responded to my questions and requests for help by providing insightful and valuable advice. In particular, I would like to thank Dr. Waters for hiring me as his Research Assistant; the experience has been invaluable and it has been a pleasure to work alongside such a generous and talented professor. -

Issue #100 Technicaltidbits Materion Performance Alloys

APRIL 2017 ISSUE #100 TECHNICALTIDBITS MATERION PERFORMANCE ALLOYS LEARNING FROM FAILURES AND ENGINEERING DISASTERS As an engineer, you can learn more from a single failure than Disasters frequently from 1000 successes. happen outside of This is especially true if the failure is your own design, • Dam collapses (South Fork Dam, Sayano- 1970’s Hollywood as the lessons are personal and deeply ingrained. Shushenskaya Dam, St. Francis Dam) movies. – Using However, you do not have to learn from your own • Failure of Levees around New Orleans during short-term testing to failures, as engineers, architects and designers have Hurricane Katrina been making design mistakes (and occasionally estimate long-term failure • Therac-25 overdoses goofing up royally) for millennia. The point here is not to learn to assign blame. It is After any engineering disaster, there is always an important to study not just how something failed, but inquiry to determine who or what was responsible. why it failed. Here are some key considerations to Failure Those approaching an inquiry from a legal point of look for when examining historical failures: view are most interested in finding out if anyone Engineering should be paying compensation and whether or • What decisions led to the failure? Disaster not criminal charges should be filed. Engineers can aid • Was a previously unknown natural phenomenon this effort as expert witnesses, but the most import- to blame (like aeroelastic flutter in the Tacoma ant role of the engineer is to find out exactly what Narrows Bridge collapse, or the trench effect in went wrong, so that the disaster is never repeated. -

Sanchez Udel 0060D 1

RADIOACTIVE REVERSAL? THE FUKUSHIMA ACCIDENT AS A FOCUSING EVENT FOR COMPARATIVE POLICY CHANGE ON NUCLEAR ENERGY by Victoria Justine Sanchez A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science and International Relations. Summer 2017 © 2017 Victoria Justine Sanchez All Rights Reserved RADIOACTIVE REVERSAL? THE FUKUSHIMA ACCIDENT AS A FOCUSING EVENT FOR COMPARATIVE POLICY CHANGE ON NUCLEAR ENERGY by Victoria Justine Sanchez Approved: __________________________________________________________ David P. Redlawsk, Ph.D. Chair of the Department of Political Science and International Relations Approved: __________________________________________________________ George H. Watson, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Approved: __________________________________________________________ Ann L. Ardis, Ph.D. Senior Vice Provost for Graduate and Professional Education I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signed: __________________________________________________________ Janet B. Johnson, Ph.D. Professor in charge of dissertation I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signed: __________________________________________________________ -

Dimensions of Disaster During Hurricane Katrina: Landscape

Dimensions of Disaster During Hurricane Katrina: Landscape, Levees, and the Least Fortunate Sarah McKinnell Geography Department – Fall 2012 Professor William Travis – Head Advsior – Geography Department Professor Stefan Leyk – Geography Department Professor Mary Kraus – Geology Department Abstract: In 2005 Hurricane Katrina made landfall in Southeastern Louisiana as a powerful Category Three hurricane. The hurricane protection systems in place for the city of New Orleans and surrounding parishes were overwhelmed sending billions of gallons of water into local communities. This atypical flood volume inundated 80% of New Orleans, impeding rescue efforts and devastating infrastructure and emergency resources. Over 1,500 lives were lost and an estimated 125 billion US dollars were spent on emergency response, recovery, and reconstruction. Hurricane Katrina is the worst disaster in the United States in over a century. This paper analyzes why Hurricane Katrina was such a catastrophe. Three major reasons for disaster are identified: construction of piecemeal levee systems, wetland loss, and social vulnerabilities. Throughout the history of southeastern Louisiana’s settlement, the natural hydrography was manipulated in order to protect life and property from flooding; a fragmented levee system was constructed based on underestimated storm risk resulting in the hurricane protection system that failed during Hurricane Katrina. Similarly, increased residential development, canal building, and natural land subsidence processes have degraded natural wetlands which function as protective barriers from storm surges. The population of New Orleans exhibited high social vulnerabilities, as many Katrina victims lacked the tools, knowledge, and capabilities necessary to evacuate in a timely manner or to exercise other self-protective measures. These three elements—fragmented levee systems, wetland degradation, and high social vulnerabilities—exacerbate the level of vulnerability of property and people along the Gulf Coast. -

COURSE DESCRIPTIONS Fall 2021 Bulletin

UNDERGRADUATE COURSE DESCRIPTIONS Fall 2021 Bulletin and modern languages, the caste system An introduction to the stories, histories, and AAS and reform movements, Asohka, Akbar and aesthetics of Indian classical performing great emperors, impact of Islam and Western arts. The course focuses on Bharatanatyam, Asian & Asian American colonization, and Gandhi and the impact of the solo dance form from South India. Studies South Asia on the world. Kathakali, Manipuri, Odissi, and Kathak will be introduced to compare and contrast DEC: J AAS 102: Eastern Religions dance-theatre forms of South Asia. Students SBC: GLO Historical introduction to Hinduism, will be introduced to each performance form Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism. 3 credits by studying its ancient and modern history, Attention is given to the cultural background, practitioners, technique, stage presentation, AAS 209: Indian Classical Dance: art, literature, philosophy, and institutional and aesthetics. The course explores the Bharatanatyam development of each tradition. This course is commonalities of all these performing art offered as both AAS 102 and RLS 102. Introduction to the basics of Bharatanatyam forms including: mythology, the classic text: (South Indian classical dance) technique. Natya Shastra, abhinaya (mime) and the DEC: B Includes primary postures and basic steps, theory of rasa. Lessons will be accompanied SBC: GLO, HUM or adavus. Class also covers the theory of by suitable reading material and visual 3 credits Bharatanatyam including hand gestures, head, demonstrations either on video or by a neck and eye movements, as delineated in practitioner of the art form. AAS 110: Appreciating Indian Music Nandikeswara's Abhinaya Darpana. Students DEC: D An introduction to the basic elements of Indian will gain a well-rounded knowledge of the SBC: ARTS classical music, such as "raga" and "tala", dance by studying Bharatanatyam's form, "gharanas" (schools) and styles. -

Compensating Victims of Bridge Collapses Outside Minnesota (2007)

Compensating Victims of Bridge Collapses Outside Minnesota Peter S. Wattson Senate Counsel State of Minnesota November 9, 2007 2 Contents Introduction ................................................................ ii 1. Tacoma Narrows Bridge - Washington - November 7, 1940 ....................1 2. Silver Bridge - West Virginia - December 15, 1967 ...........................2 3. Mianus River Bridge - Connecticut - June 28, 1983 ...........................3 4. Schoharie Creek Bridge - New York - April 5, 1987 ..........................4 5. Hatchie River Bridge - Tennessee - April 1, 1989 .............................6 6. San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge and Cypress Structure - California - October 17, 1989 ...............................................................7 7. Little Red River Pedestrian Bridge - Arkansas - October 29, 1989 ..............9 8. I-40 Bridge Near Webbers Falls - Oklahoma - May 26, 2002 ..................10 Conclusion .................................................................11 Bridge Collapse Web Sites ....................................................12 i Introduction This paper describes how other states have compensated victims of bridge collapses that occurred before the Interstate 35W Bridge over the Mississippi River in Minneapolis collapsed on August 1, 2007. It includes bridges that collapsed in California, Connecticut, New York, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Washington, and West Virginia, from 1940 to 2002. The collapses and the state response to them are described in chronological order. They offer an -

Engineering Disasters: Learning from Failure

Engineering Disasters: Learning from Failure N. Chawla School of Materials Fulton School of Engineering Arizona State University Tempe, AZ 85287-8706 [email protected] http://enpub.fulton.asu.edu/chawla/Home.htm (480) 965-2402 (phone) (480) 727-9321 (fax) Submitted to: TMS Education Resource Awards November 2007 Engineering Disasters: Learning from Failure • Engineering disasters have resulted in loss of life, injuries, and billions of dollars in damage. • Primary causes for engineering disasters: – Design flaws – Material failures – Extreme conditions or environments (not necessarily preventable) – Some combinations of the reasons above. • Three major disasters: – Sinking of the ship Titanic – Collapse of the World Trade Center buildings – Explosion of the Space Shuttle Columbia Chronology of Events Leading to Sinking of the Titanic • Titanic began its maiden voyage to New York at noon on April 10, 1912, from Southampton, England. • On night of April 14, at 11:40 p.m., crew sighted an iceberg immediately ahead of ship. • In about 40 seconds it collided with an iceberg estimated to have a gross weight of 150,000-300,000 tons. • Iceberg struck the Titanic near bow and raked side of ship's hull damaging hull plates and popping rivets, • At 2:20 a.m., April 15, 1912, Titanic sank within two hours and 40 minutes, with the loss of more than 1,500 lives. Why did the Titanic sink? • Theory 1 Multiple rivet failures upon collision with iceberg. • Theory 2 Failure of the steel hull upon collision with iceberg. Remains of the Titanic Theory 1: Multiple wrought-Fe rivet failures upon collision with iceberg. -

Space Shuttle Case Studies: Challenger and Columbia

Paper ID #8419 Space Shuttle Case Studies: Challenger and Columbia Dr. Scott L Post, Bradley University Scott Post received his Ph.D. in Mechanical Engineering from Purdue University. He is currently an Asso- ciate Professor at Bradley University in Peoria, IL. He has previously worked as an Assistant Professor at Michigan Technological University. He has also been a summer Faculty Fellow at NASA Dryden Flight Research Center, and a Visiting Erskine Fellow at the University of Canterbury in Christchurch, New Zealand. c American Society for Engineering Education, 2014 Space Shuttle Case Studies: Challenger and Columbia Abstract The two Space Shuttle tragedies, Challenger and Columbia, have led to many papers on case studies on engineering ethics. The Challenger disaster in particular is often discussed due to the infamous teleconference that took place the night before the launch in which some engineers tried to postpone the launch. However, the space shuttle program itself is worthy of study as it relates to the engineering design process, and the details of the Challenger and Columbia disasters are worthy of discussion as they relate to a variety of sub-disciplines, including material science, thermodynamics, fluid mechanics, and heat transfer. This paper summarizes the major technical findings of the Rogers Commission and the Columbia Accident Investigation Board (CAIB). An overview of the history of the space shuttle program, going back to the end of the Apollo program, is presented, including some of the design compromises that were made in order to get political support for the space shuttle program. A detailed bibliography is given that will aid instructors in finding additional material they can tailor to their particular class needs. -

Levees, Urbanization and Public Perception: Implications for Southeast Louisiana Wetlands

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 8-6-2009 Levees, Urbanization and Public Perception: Implications for Southeast Louisiana Wetlands Jacquelyn Marchand University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Marchand, Jacquelyn, "Levees, Urbanization and Public Perception: Implications for Southeast Louisiana Wetlands" (2009). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 983. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/983 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Levees, Urbanization and Public Perception: Implications for Southeast Louisiana Wetlands A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Geography by Jacquelyn Ann Marchand B.A. University of New Orleans, -

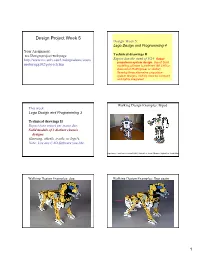

Design Project Week 5

Design Project Week 5 Design Week 5: Lego Design and Programming 4 Your Assignment: see Design project web page: Technical drawings II http://www.me.unlv.edu/Undergraduate/cours Report due the week of 9/24: Robot propulsion system design. Use of Solid enotes/egg102/proj-sch.htm modeling software is preferred (MLCAD or Autocad or ProEngineer or similar). Develop three alternative propulsion system designs. Vehicle must be compact and tightly integrated. Walking Design Examples: Biped This week: Lego Design and Programming 3 Technical drawings II Report (one report per team) due: Solid models of 3 distinct chassis designs (Steering, wheels, tracks, or legs?). Note: Use any CAD Software you like. http://home.earthlink.net/~xaos69/NXT/AlphaRex_Avoid_Obstacle/AlphaRex_Avoid_Obst Walking Design Examples: dog Walking Design Examples: Dog again 1 Steering Example Steering Example NASA Sojourner Steering System Detail NASA Sojourner Rack and Pinion Steering Rack and Pinion Steering Rack and Pinion Steering II 2 Rack and Pinion Steering II , Top Rack and Pinion Steering II, Front View View Gears I Gears II Gears III GearsGears IV IV Differential Differential 3 Simple Steering Multiple Gears Walking Design Examples 2 wheels in front are propelled. Rear caster wheel is trailing. Eight-Legged Walker. view animation on web! Walking Design Examples Walking Design Examples HUBO-FX1 is a robot designed to walk naturally, carrying a person (or whatever) weighing up to 220 pounds. Six-Legged Walker http://ohzlab.kaist.ac.kr/index.php 4 Please note: Chapter 1.10 Professionalism These illustrations are meant to give you ideas. I suggest you visit Lego-related web sites for more information.