Local Power in Colonial and Contemporary Goa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newspaper Wise.Xlsx

PRINT MEDIA COMMITMENT REPORT FOR DISPLAY ADVT. DURING 2013-2014 CODE NEWSPAPER NAME LANGUAGE PERIODICITY COMMITMENT(%)COMMITMENTCITY STATE 310672 ARTHIK LIPI BENGALI DAILY(M) 209143 0.005310639 PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 100771 THE ANDAMAN EXPRESS ENGLISH DAILY(M) 775695 0.019696744 PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 101067 THE ECHO OF INDIA ENGLISH DAILY(M) 1618569 0.041099322 PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 100820 DECCAN CHRONICLE ENGLISH DAILY(M) 482558 0.012253297 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410198 ANDHRA BHOOMI TELUGU DAILY(M) 534260 0.013566134 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410202 ANDHRA JYOTHI TELUGU DAILY(M) 776771 0.019724066 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410345 ANDHRA PRABHA TELUGU DAILY(M) 201424 0.005114635 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410522 RAYALASEEMA SAMAYAM TELUGU DAILY(M) 6550 0.00016632 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410370 SAKSHI TELUGU DAILY(M) 1417145 0.035984687 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410171 TEL.J.D.PATRIKA VAARTHA TELUGU DAILY(M) 546688 0.01388171 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410400 TELUGU WAARAM TELUGU DAILY(M) 154046 0.003911595 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410495 VINIYOGA DHARSINI TELUGU MONTHLY 18771 0.00047664 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410398 ANDHRA DAIRY TELUGU DAILY(E) 69244 0.00175827 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410449 NETAJI TELUGU DAILY(E) 153965 0.003909538 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410012 ELURU TIMES TELUGU DAILY(M) 65899 0.001673333 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410117 GOPI KRISHNA TELUGU DAILY(M) 172484 0.00437978 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410009 RATNA GARBHA TELUGU DAILY(M) 67128 0.00170454 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410114 STATE TIMES TELUGU DAILY(M) -

Planting Power ... Formation in Portugal.Pdf

Promotoren: Dr. F. von Benda-Beckmann Hoogleraar in het recht, meer in het bijzonder het agrarisch recht van de niet-westerse gebieden. Ir. A. van Maaren Emeritus hoogleraar in de boshuishoudkunde. Preface The history of Portugal is, like that of many other countries in Europe, one of deforestation and reafforestation. Until the eighteenth century, the reclamation of land for agriculture, the expansion of animal husbandry (often on communal grazing grounds or baldios), and the increased demand for wood and timber resulted in the gradual disappearance of forests and woodlands. This tendency was reversed only in the nineteenth century, when planting of trees became a scientifically guided and often government-sponsored activity. The reversal was due, on the one hand, to the increased economic value of timber (the market's "invisible hand" raised timber prices and made forest plantation economically attractive), and to the realization that deforestation had severe impacts on the environment. It was no accident that the idea of sustainability, so much in vogue today, was developed by early-nineteenth-century foresters. Such is the common perspective on forestry history in Europe and Portugal. Within this perspective, social phenomena are translated into abstract notions like agricultural expansion, the invisible hand of the market, and the public interest in sustainably-used natural environments. In such accounts, trees can become gifts from the gods to shelter, feed and warm the mortals (for an example, see: O Vilarealense, (Vila Real), 12 January 1961). However, a closer look makes it clear that such a detached account misses one key aspect: forests serve not only public, but also particular interests, and these particular interests correspond to specific social groups. -

From an Autonomous Province to a Habsburg Principality

FROM AN AUTONOMOUS PROVINCE TO A HABSBURG PRINCIPALITY. THE LEGISLATIVE ROLE OF THE TRANSYLVANIAN DIET DURING THE 18TH CENTURY Gelu Fodor* Keywords: Werböczy, Tripartitum, constitution, Diet, Pragmatic Sanction, legislative system Cuvinte cheie: Werböczy, Tripartitum, constituţie, dietă, Pragmatica Sancţiune, sistem legislativ Introductory considerations Our approach aims to shed light on the evolution of the Transylvanian constitution and constitutionalism after the incorporation of the Principality of Transylvania within the administrative structures of the Habsburg Empire, the upper chronological limit being the provisions the Diet issued in 1791. In order to achieve this goal, we intend to examine all the aspects that contributed decisively to shaping the constitutional realities in the Principality, focusing in particular on the institutional and legislative role of the Diet, as a representative authority for the nobility in its relationship with the Habsburg sovereigns. The conquest of Transylvania by the Habsburgs gradually brought about major changes as regards the law-making institutions, and some of these changes were made with the direct involvement of the Diet. The central aspect on which we shall dwell and which, in our opinion, was the quintessence of the entire legislative process unfolding throughout the 18th century, revolved around the articles of law enacted by the Diet of 1744 and, respectively, of the Diet of 1791. By analysing their specific provisions, we shall attempt to highlight the changes that took place in the constitutional structure of the Principality up until the turn of the 19th century. Another point of interest for our study revolves around what certain historians regard as the very foundation of the Transylvanian political system, namely the Constitutions of Transylvania: Werböczy’s Tripartitum, Aprobatae Constitutiones and Compilatae Constitutiones. -

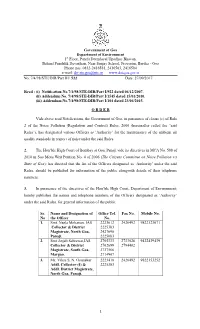

Government of Goa Department of Environment 1 Floor, Pandit Deendayal Upadhay Bhavan, Behind Pundalik Devasthan, Near Sanjay

Government of Goa Department of Environment 1st Floor, Pandit Deendayal Upadhay Bhavan, Behind Pundalik Devasthan, Near Sanjay School, Provorim, Bardez - Goa Phone nos. 0832-2416581, 2416583, 2416584 e-mail: [email protected] www.dstegoa.gov.in No: 7/4/98/STE/DIR/Part III/ 522 Date: 27/09/2017 Read : (i) Notification No.7/4/98/STE-DIR/Part I/922 dated 04/12/2007. (ii) Addendum No. 7/4/98/STE-DIR/Part I/1545 dated 15/01/2010. (iii) Addendum No.7/4/98/STE-DIR/Part I/104 dated 23/04/2015. O R D E R Vide above read Notifications, the Government of Goa, in pursuance of clause (c) of Rule 2 of the Noise Pollution (Regulation and Control) Rules, 2000 (hereinafter called the “said Rules”), has designated various Officers as ‘Authority’ for the maintenance of the ambient air quality standards in respect of noise under the said Rules. 2. The Hon’ble High Court of Bombay at Goa, Panaji vide its directives in MCA No. 588 of 2010 in Suo Motu Writ Petition No. 4 of 2006 (The Citizens Committee on Noise Pollution v/s State of Goa); has directed that the list of the Officers designated as ‘Authority’ under the said Rules, should be published for information of the public alongwith details of their telephone numbers. 3. In pursuance of the directives of the Hon’ble High Court, Department of Environment; hereby publishes the names and telephone numbers of the Officers designated as ‘Authority’ under the said Rules, for general information of the public. -

Annualrepeng II.Pdf

ANNUAL REPORT – 2007-2008 For about six decades the Directorate of Advertising and on key national sectors. Visual Publicity (DAVP) has been the primary multi-media advertising agency for the Govt. of India. It caters to the Important Activities communication needs of almost all Central ministries/ During the year, the important activities of DAVP departments and autonomous bodies and provides them included:- a single window cost effective service. It informs and educates the people, both rural and urban, about the (i) Announcement of New Advertisement Policy for nd Government’s policies and programmes and motivates print media effective from 2 October, 2007. them to participate in development activities, through the (ii) Designing and running a unique mobile train medium of advertising in press, electronic media, exhibition called ‘Azadi Express’, displaying 150 exhibitions and outdoor publicity tools. years of India’s history – from the first war of Independence in 1857 to present. DAVP reaches out to the people through different means of communication such as press advertisements, print (iii) Multi-media publicity campaign on Bharat Nirman. material, audio-visual programmes, outdoor publicity and (iv) A special table calendar to pay tribute to the exhibitions. Some of the major thrust areas of DAVP’s freedom fighters on the occasion of 150 years of advertising and publicity are national integration and India’s first war of Independence. communal harmony, rural development programmes, (v) Multimedia publicity campaign on Minority Rights health and family welfare, AIDS awareness, empowerment & special programme on Minority Development. of women, upliftment of girl child, consumer awareness, literacy, employment generation, income tax, defence, DAVP continued to digitalize its operations. -

FIDI Customs Guide for Portugal

Customs Guide PORTUGAL Information from FIDI Portugal Customs guide PORTUGAL The global quality standard for international moving. The FAIM label is your global assurance for a smooth, safe and comprehensive relocation process. GOODS DOCUMENTS REQUIRED CUSTOMS PRESCRIPTIONS REMARKS Removal Goods - Private persons, coming from . " Certificado de Bagagem " issued by . Declarations to be supplied by the agent at . Normally, household removals should be non-EEC countries only Portuguese Consulate at origin together destination and signed at agent's office. imported in 1 single shipment, from 1 place with a comprehensive inventory list in of origin. Portuguese, stating that all items are used . Importation Customs Clearance Charges: . In special circumstances and on and have been in Owner’s possession for submission of proofs and explanation to more than 12 months (do not show values). Although normal removal goods are duty the General Customs Board, prior to the . Original Passport of Owner (in force and free, there are always customs broker removal, it is possible to obtain the stating place of residence abroad). fees to be considered which are based on necessary permission to import . Certificate stating that Owner lived abroad ad-valorem. Port handling charges and household goods in 2 or more shipments. for more than 1 year and is cancelling his warehouse fees are included in these . A full inventory must be produced with residence at origin. charges (rather expensive - quotations the first consignment showing clearly . Domicile certificate (Atestado de residencia) should be requested). which goods are being imported in the to be obtained by the client, issued by the first consignment and which belong to "Junta de Freguesia" at client's residence in . -

List of Subjects, Admission of New Subjects Article 66

Chapter 3. Federative Arrangement (Articles 65–79) 457 Chapter 3. Federative Arrangement See also Art.5 Federative arrangement Article 65: List of subjects, admission of new subjects Art.65.1. The composition of the RF comprises the following RF subjects: the Republic Adygeia (Adygeia), the Republic Altai, the Republic Bashkortostan, the Republic Buriatia, the Republic Dagestan, the Republic Ingushetia, the Kabarda-Balkar Republic, the Republic Kalmykia, the Karachai-Cherkess Republic, the Republic Karelia, the Republic Komi, the Republic Mari El, the Republic Mordovia, the Republic Sakha (Iakutia), the Republic North Ossetia- Alania, the Republic Tatarstan (Tatarstan), the Republic Tyva, the Udmurt Republic, the Republic Khakasia, the Chechen Republic, and the Chuvash Republic-Chuvashia; Altai Territory, Krasnodar Territory, Krasnoiarsk Territory, Primor’e Territory, Stavropol’ Territory, and Khabarovsk Territory; Amur Province, Arkhangel’sk Province, Astrakhan’ Province, Belgorod Province, Briansk Province, Vladimir Province, Volgograd Province, Vologda Province, Voronezh Province, Ivanovo Province, Irkutsk Province, Kaliningrad Province, Kaluga Province, Kamchatka Province, Kemerovo Province, Kirov Province, Kostroma Province, Kurgan Province, Kursk Province, Leningrad Province, Lipetsk Province, Magadan Province, Moscow Province, Murmansk Province, Nizhnii Novgorod Province, Novgorod Province, Novosibirsk Province, Omsk Province, Orenburg Province, Orel Province, Penza Province, Perm’ Province, Pskov Province, Rostov Province, Riazan’ -

Folk Theatre in Goa: a Critical Study of Select Forms Thesis

FOLK THEATRE IN GOA: A CRITICAL STUDY OF SELECT FORMS THESIS Submitted to GOA UNIVERSITY For the Award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by Ms. Tanvi Shridhar Kamat Bambolkar Under the Guidance of Dr. (Mrs.) K. J. Budkuley Professor of English (Retd.), Goa University. January 2018 CERTIFICATE As required under the University Ordinance, OA-19.8 (viii), I hereby certify that the thesis entitled, Folk Theatre in Goa: A Critical Study of Select Forms, submitted by Ms. Tanvi Shridhar Kamat Bambolkar for the Award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English has been completed under my guidance. The thesis is the record of the research work conducted by the candidate during the period of her study and has not previously formed the basis for the award of any Degree, Diploma, Associateship, Fellowship or other similar titles to her by this or any other University. Dr. (Mrs.) K.J.Budkuley Professor of English (Retd.), Goa University. Date: i DECLARATION As required under the University Ordinance OA-19.8 (v), I hereby declare that the thesis entitled, Folk Theatre in Goa: A Critical Study of Select Forms, is the outcome of my own research undertaken under the guidance of Dr. (Mrs.) K.J.Budkuley, Professor of English (Retd.),Goa University. All the sources used in the course of this work have been duly acknowledged in the thesis. This work has not previously formed the basis of any award of Degree, Diploma, Associateship, Fellowship or other similar titles to me, by this or any other University. Ms. -

Re: RFP AID/NEB-00038 Portupal "Report on Development of An

Re: RFP AID/NEB-00038 Portupal "Report on Development of an Integrated Manageiient Information System in the Areas of Ambulatory Services, Hospital Dischar, 'es, and. Finance for the Ministry of Social Assurance and. Public Health, Government of Portugal, 15 January 1982" Report on Development of an Integrated Management Information System in the Areas of Ambulatory Services, Hospital Discharges, and Finance for the Ministry of Social Assurance and Public Health Government of Portu,.al submitted to: The United States Agency for International Development Lisbon, Portugal by A. Frederick Hartman, MD MPH Rachel Feilden, M.P.A. Paul Desjardins, B.Sc. Catherine Overholt, Ph.D. Donald Holloway, Ph.D. Management Sciences for Health 141 Tremont Street Boston, Massachusetts 02111 January 1]5, 1982 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report presents the analysis and recommendations of a team of consultants requested by the Secretary of State for Health to assist in the development of an integrated Management Information System (MIS) for health. A team of five people was provided in the following areas: - Health Planning/Epidemologist to provide overall coordination and assist in development of ambulatory service and hospital discharge information. - Hospital administrator to develop a framework for productivity analysis of hospitals and allocation of resources accordingly. - Financial Analyst to assist in assessing controllable vs. non controllable costs and simplification of reports. - Systems Analyst to assist in preparation of a field test of the MIS in 1982. - Senior Programmer to assist SIS in the functional analysis for data processing. In the areas of ambulatory service and hospital discharge information, a unified form was developed to be used by all the major health service divisions (DGH, DGS, and SMS) for each category. -

Hon'ble Governor's Address-2021 to the Goa Legislative Assembly

Mr. Speaker and Hon’ble Members of the Goa Legislative Assembly, 1. It gives me immense pleasure and honour to address this August House on the onset of New year. I take this opportunity to convey my heartiest New Year Greetings to each one of you and extend a warm welcome to all the Members of the August House on my first address during the thirteenth session of the Goa Legislative Assembly. 2. I am happy to say that we have entered the sixtieth year (Diamond Jubilee) of Goa‟s Liberation and were delighted by the presence of Shri Ram Nath Kovind ji, the first ever occasion that Hon‟ble President of India participated in the celebrations of Goa‟s Liberation Day. During the inaugural speech, the Hon‟ble President of India lauded the Uniform 1 Civil Code in force in the State and termed it as a matter of pride. 3. At the outset, I would like to congratulate the Hon‟ble Chief Minister and his Cabinet Collegues, State Executive Committee headed by the Chief Secretary, all front line Covid warriors, Officers and officials who successfully controlled the spread of COVID-19 (pandemic) in the State. Though the State has suffered a lot in terms of Socio-Economic & Infrastructure development taking a backseat in the Covid times, but due to systematic planning, regular monitoring and instantaneous corrective measures by the State administration, the State is now gaining momentum in its activities from micro to macro level and is nearing complete normalcy. The Hon‟ble Prime Minister has announced “Atmanirbhar Bharat- Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Yojana” in the country, which has extended handholding support to all States for the survival of various sections of people of the society with unity and integrity 2 “Ek Bharat–Shreshtha Bharat”. -

GOVERNMENT of GOA Panaji, 23Rd June, 2011

Reg. No. GR/RNP/GOA/32 RNI No. GOAENG/2002/6410 Panaji, 28th July, 2011 (Sravana 6, 1933) SERIES II No. 17 PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY Note:- There is one Extraordinary issue to the Official registered under code symbol No. ARCS/CZ/GEN/ Gazette, Series II No. 16 dated 21-7-2011 namely:- /12(c)/1/SHG/Goa. Extraordinary dated 21-7-2011 from pages 391 to 392 regarding Notification from Department Sd/- (A. K. N. Desai), Asstt. Registrar of Co-op. of Elections (Office of the Chief Electoral Officer). Societies (Central Zone). GOVERNMENT OF GOA Panaji, 23rd June, 2011. Department of Civil Supplies and Certificate of Registration Consumer Affairs “The Saheli Self Help Group Co-operative Society __ Ltd.”, Vaddy, Merces, Tiswadi-Goa is registered on Order 23-06-2011 and it bears registration No. ARCS/CZ/ /GEN/12(c)/1/SHG/Goa and it is classified as No. 1/6/2000/2011-CSD/101 “General Society”, under sub-classification The Government of Goa is pleased to accept the No. 12(c), as “Other Society,” in terms of Rule 8(1), resignation tendered by Hon’ble Justice (Retd.) of the Goa Co-operative Societies Rules, 2003 for Shri D. Govindrao Deshpande from the post of the State of Goa. “President of Consumer Disputes Redressal Commission (State Commission) of Goa, Panaji” with Sd/- (A. K. N. Desai), Asstt. Registrar of Co-op. effect from 1st July, 2011. Societies (Central Zone). By order and in the name of the Governor of Panaji, 23rd June, 2011. Goa. _________ Gurudas P. Pilarnkar, Director and ex officio Joint Notification Secretary (Civil Supplies and Consumer Affairs). -

Chapter 6: EPILOGUE I. Significance of the Study A) the Study Is Basically

Chapter 6: EPILOGUE I. Significance of the study a) The study is basically a very good documentation of Goa's ancient and medieval period icons and sculptural remains. So far a wrong notion among many that Goa religio cultural past before the arrival of the Portuguese is intangible has been critically viewed and examined in this study. The research would help in throwing light on the pre-Portuguese era of the Goa's history. b) The craze of modernization and renovation of ancient and historic temples have made changes in the religio-cultural aspect of the society. Age old deities and concepts of worships have been replaced with new sculptures or icons. The new sculptures installed in places of the historic ones have been modified to the whims and fancies of many trustees or temple authorities thus changing the pattern of the religio-cultural past. While new icons substitute the old ones there are changes in attributes, styles and the historic features of the sculpture or image. Not just this but the old sculptures are immersed in water when the new one is being installed. Some customary rituals have been rapidly changed intentionally or unintentionally by the stake holders or the devotees. Moreover the most of the ancient rituals and customs associated with some icons have are in process of being stopped by the locals. Therefore a thorough documentation of these sculptures and antiquities with scientific attitude and research was the need of the hour. c) The iconographic details about many sculptures, worships or deities are scattered in many books and texts.