The Interaction Between Postminimalist Music and Contemporary Dance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Is a Genre of Dance Performance That Developed During the Mid-Twentieth

Contemporary Dance Dance 3-4 -Is a genre of dance performance that developed during the mid-twentieth century - Has grown to become one of the dominant genres for formally trained dancers throughout the world, with particularly strong popularity in the U.S. and Europe. -Although originally informed by and borrowing from classical, modern, and jazz styles, it has since come to incorporate elements from many styles of dance. Due to its technical similarities, it is often perceived to be closely related to modern dance, ballet, and other classical concert dance styles. -It also employs contract-release, floor work, fall and recovery, and improvisation characteristics of modern dance. -Involves exploration of unpredictable changes in rhythm, speed, and direction. -Sometimes incorporates elements of non-western dance cultures, such as elements from African dance including bent knees, or movements from the Japanese contemporary dance, Butoh. -Contemporary dance draws on both classical ballet and modern dance -Merce Cunningham is considered to be the first choreographer to "develop an independent attitude towards modern dance" and defy the ideas that were established by it. -Cunningham formed the Merce Cunningham Dance Company in 1953 and went on to create more than one hundred and fifty works for the company, many of which have been performed internationally by ballet and modern dance companies. -There is usually a choreographer who makes the creative decisions and decides whether the piece is an abstract or a narrative one. -Choreography is determined based on its relation to the music or sounds that is danced to. . -

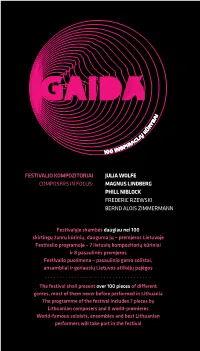

Julia Wolfe Magnus Lindberg Phill Niblock Frederic

FESTIVALIO KOMPOZITORIAI JULIA WOLFE COMPOSERS IN FOCUS: MAGNUS LINDBERG PHILL NIBLOCK FREDERIC RZEWSKI BERND ALOIS ZIMMERMANN Festivalyje skambės daugiau nei 100 skirtingų žanrų kūrinių, dauguma jų – premjeros Lietuvoje Festivalio programoje – 7 lietuvių kompozitorių kūriniai ir 8 pasaulinės premjeros Festivalio puošmena – pasaulinio garso solistai, ansambliai ir geriausių Lietuvos atlikėjų pajėgos The festival shall present over 100 pieces of different genres, most of them never before performed in Lithuania The programme of the festival includes 7 pieces by Lithuanian composers and 8 world-premieres World-famous soloists, ensembles and best Lithuanian performers will take part in the festival PB 1 PROGRAMA | TURINYS In Focus: Festivalio dėmesys taip pat: 6 JULIA WOLFE 18 FREDERIC RZEWSKI 10 MAGNUS LINDBERG 22 BERND ALOIS ZIMMERMANN 14 PHILL NIBLOCK 24 Spalio 20 d., šeštadienis, 20 val. 50 Spalio 26 d., penktadienis, 19 val. Vilniaus kongresų rūmai Šiuolaikinio meno centras LAURIE ANDERSON (JAV) SYNAESTHESIS THE LANGUAGE OF THE FUTURE IN FAHRENHEIT Florent Ghys. An Open Cage (2012) 28 Spalio 21 d., sekmadienis, 20 val. Frederic Rzewski. Les Moutons MO muziejus de Panurge (1969) SYNAESTHESIS Meredith Monk. Double Fiesta (1986) IN CELSIUS Julia Wolfe. Stronghold (2008) Panayiotis Kokoras. Conscious Sound (2014) Julia Wolfe. Reeling (2012) Alexander Schubert. Sugar, Maths and Whips Julia Wolfe. Big Beautiful Dark and (2011) Scary (2002) Tomas Kutavičius. Ritus rhythmus (2018, premjera)* 56 Spalio 27 d., šeštadienis, 19 val. Louis Andriessen. Workers Union (1975) Lietuvos nacionalinė filharmonija LIETUVOS NACIONALINIS 36 Spalio 24 d., trečiadienis, 19 val. SIMFONINIS ORKESTRAS Šiuolaikinio meno centras RŪTA RIKTERĖ ir ZBIGNEVAS Styginių kvartetas CHORDOS IBELHAUPTAS (fortepijoninis duetas) Dalyvauja DAUMANTAS KIRILAUSKAS COLIN CURRIE (kūno perkusija, (fortepijonas) Didžioji Britanija) Laurie Anderson. -

All These Post-1965 Movements Under the “Conceptual Art” Umbrella

All these post-1965 movements under the “conceptual art” umbrella- Postminimalism or process art, Site Specific works, Conceptual art movement proper, Performance art, Body Art and all combinations thereof- move the practice of art away from art-as-autonomous object, and art-as-commodification, and towards art-as-experience, where subject becomes object, hierarchy between subject and object is critiqued and intersubjectivity of artist, viewer and artwork abounds! Bruce Nauman, Live-Taped Video Corridor, 1970, Conceptual Body art, Postmodern beginning “As opposed to being viewers of the work, once again they are viewers in it.” (“Subject as Object,” p. 199) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9IrqXiqgQBo A Postmodern beginning: Body art and Performance art as critique of art-as-object recap: -Bruce Nauman -Vito Acconci focus on: -Chris Burden -Richard Serra -Carolee Schneemann - Hannah Wilke Chapter 3, pp. 114-132 (Carolee Schneemann and Hannah Wilke, First Generation Feminism) Bruce Nauman, Bouncing Two Balls Between the Floor and Ceiling with Changing Rhythms, 1967-1968. 16mm film transferred to video (black and white, sound), 10 min. Body art/Performance art, Postmodern beginning- performed elementary gestures in the privacy of his studio and documented them in a variety of media Vito Acconci, Following Piece, 1969, Body art, Performance art- outside the studio, Postmodern beginning Video documentation of the event Print made from bite mark Vito Acconci, Trademarks, 1970, Body art, Performance art, Postmodern beginning Video and Print documentation -

Dance, Senses, Urban Contexts

DANCE, SENSES, URBAN CONTEXTS Dance and the Senses · Dancing and Dance Cultures in Urban Contexts 29th Symposium of the ICTM Study Group on Ethnochoreology July 9–16, 2016 Retzhof Castle, Styria, Austria Editor Kendra Stepputat Copy-editors Liz Mellish Andriy Nahachewsky Kurt Schatz Doris Schweinzer ICTM Study Group on Ethnochoreology Institute of Ethnomusicology, University of Music and Performing Arts Graz Graz, Austria 2017 Symposium 2016 July 9–16 International Council for Traditional Music Study Group on Ethnochoreology The 29th Symposium was organized by the ICTM Study Group on Ethnochoreology, and hosted by the Institute of Ethnomusicology, University of Music and Perfoming Arts Graz in cooperation with the Styrian Government, Sections 'Wissenschaft und Forschung' and 'Volkskultur' Program Committee: Mohd Anis Md Nor (Chair), Yolanda van Ede, Gediminas Karoblis, Rebeka Kunej and Mats Melin Local Arrangements Committee: Kendra Stepputat (Chair), Christopher Dick, Mattia Scassellati, Kurt Schatz, Florian Wimmer Editor: Kendra Stepputat Copy-editors: Liz Mellish, Andriy Nahachewsky, Kurt Schatz, Doris Schweinzer Cover design: Christopher Dick Cover Photographs: Helena Saarikoski (front), Selena Rakočević (back) © Shaker Verlag 2017 Alle Rechte, auch das des auszugsweisen Nachdruckes der auszugsweisen oder vollständigen Wiedergabe der Speicherung in Datenverarbeitungsanlage und der Übersetzung vorbehalten. Printed in Germany ISBN 978-3-8440-5337-7 ISSN 0945-0912 Shaker Verlag GmbH · Kaiserstraße 100 · D-52134 Herzogenrath Telefon: 0049 24 07 / 95 96 0 · Telefax: 0049 24 07 / 95 96 9 Internet: www.shaker.de · eMail: [email protected] Christopher S. DICK DIGITAL MOVEMENT: AN OVERVIEW OF COMPUTER-AIDED ANALYSIS OF HUMAN MOTION From the overall form of the music to the smallest rhythmical facet, each aspect defines how dancers realize the sound and movements. -

The Guardian.Pdf

My favourite film: Koyaanisqatsi By Leo Hickman December 13, 2011 It's a film without any characters, plot or narrative structure. And its title is notoriously hard to pronounce. What's not to love about Koyaanisqatsi? I came to Godfrey Reggio's 1982 masterpiece very late. It was actually during a Google search a few years back when looking for timelapse footage of urban traffic (for work rather than pleasure!) that I came across a "cult film", as some online reviewers were calling it. This meant I first watched it as all its loyal fans say not to: on DVD, on a small screen. If ever a film was destined for watching in a cinema, this is it. But, even without the luxury of full immersion, I was still truly captivated by it and, without any exaggeration, I still think about it every day. Koyaanisqatsi's formula is simple: combine the epic, remarkable cinematography of Ron Fricke with the swelling intensity and repeating motifs of Philip Glass's celebrated original score. There's your mood bomb, right there. But Reggio's directorial vision is key, too. He was the one who drove the project for six years on a small budget as he travelled with Fricke across the US in the mid-to-late 1970s, filming its natural and urban wonders with such originality. Koyaanisqatsi (1982) directed by Godfrey Reggio with music by Philip Glass. Photograph: Murdo Macleod for the Guardian Personally, I view the film as the quintessential environmental movie – a transformative meditation on the current imbalance between humans and the wider world that supports them (in the Hopi language, "Koyanaanis" means turmoil and "qatsi" means life). -

Taiwanese Eyes on the Modern: Cold War Dance Diplomacy And

Taiwanese Eyes on the Modern: Cold War Dance Diplomacy and American Modern Dances in Taiwan, 1950–1980 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Tsung-Hsin Lee, M.A. Graduate Program in Dance Studies The Ohio State University 2020 Dissertation Committee Hannah Kosstrin, Advisor Harmony Bench Danielle Fosler-Lussier Morgan Liu Copyrighted by Tsung-Hsin Lee 2020 2 Abstract This dissertation “Taiwanese Eyes on the Modern: Cold War Dance Diplomacy and American Modern Dances in Taiwan, 1950–1980” examines the transnational history of American modern dance between the United States and Taiwan during the Cold War era. From the 1950s to the 1980s, the Carmen De Lavallade-Alvin Ailey, José Limón, Paul Taylor, Martha Graham, and Alwin Nikolais dance companies toured to Taiwan under the auspices of the U.S. State Department. At the same time, Chinese American choreographers Al Chungliang Huang and Yen Lu Wong also visited Taiwan, teaching and presenting American modern dance. These visits served as diplomatic gestures between the members of the so-called Free World led by the U.S. Taiwanese audiences perceived American dance modernity through mixed interpretations under the Cold War rhetoric of freedom that the U.S. sold and disseminated through dance diplomacy. I explore the heterogeneous shaping forces from multiple engaging individuals and institutions that assemble this diplomatic history of dance, resulting in outcomes influencing dance histories of the U.S. and Taiwan for different ends. I argue that Taiwanese audiences interpreted American dance modernity as a means of embodiment to advocate for freedom and social change. -

It Takes Two by Carolyn Merritt

Photo: Keira Heu-Jwyn Chang It Takes Two by Carolyn Merritt What will become of us if we can’t learn to see and be with others? Can we see ourselves as others do, in order to navigate the path toward greater communication and understanding, without relinquishing our identity in the process? Together, Union Tanguera and Kate Weare Dance Company probe these questions in Sin Salida, their stunning cross-pollination of Argentine tango and contemporary dance recently presented at the Annenberg Center. Titled after Jean-Paul Sartre’s 1944 play No Exit (Huis clos in French), the production weaves together essential elements of each form with points of connection and tension, positing dance as a metaphorical map for human relations. Five chairs mark the upstage space and a single light hangs above a piano downstage left, evoking a tense audition. Film images, in negative, appear against the backdrop—a woman tending her hair at a vanity, a couple framed in a doorway, their essence muddied in the wash of black. Union Tanguera Co-Artistic Directors Claudia Codega and Esteban Moreno dance an elegant, salon-style tango that combines the outward focus and enlarged vocabulary of stage tango with the inward intention of the improvised, social Argentine form. They spin as if in balancé turns to the sounds of tango waltz, heads and focus trailing behind. Moreno lifts Codega to fan her legs wide in a split en l’air. Their costuming—stiletto heels and a tight red, knee-length dress slit to the hip for Codega, and dark dress shirt and slacks for Moreno—reference “traditional” tango aesthetics and gender dynamics. -

Expanding Horizons: the International Avant-Garde, 1962-75

452 ROBYNN STILWELL Joplin, Janis. 'Me and Bobby McGee' (Columbia, 1971) i_ /Mercedes Benz' (Columbia, 1971) 17- Llttle Richard. 'Lucille' (Specialty, 1957) 'Tutti Frutti' (Specialty, 1955) Lynn, Loretta. 'The Pili' (MCA, 1975) Expanding horizons: the International 'You Ain't Woman Enough to Take My Man' (MCA, 1966) avant-garde, 1962-75 'Your Squaw Is On the Warpath' (Decca, 1969) The Marvelettes. 'Picase Mr. Postman' (Motown, 1961) RICHARD TOOP Matchbox Twenty. 'Damn' (Atlantic, 1996) Nelson, Ricky. 'Helio, Mary Lou' (Imperial, 1958) 'Traveling Man' (Imperial, 1959) Phair, Liz. 'Happy'(live, 1996) Darmstadt after Steinecke Pickett, Wilson. 'In the Midnight Hour' (Atlantic, 1965) Presley, Elvis. 'Hound Dog' (RCA, 1956) When Wolfgang Steinecke - the originator of the Darmstadt Ferienkurse - The Ravens. 'Rock All Night Long' (Mercury, 1948) died at the end of 1961, much of the increasingly fragüe spirit of collegial- Redding, Otis. 'Dock of the Bay' (Stax, 1968) ity within the Cologne/Darmstadt-centred avant-garde died with him. Boulez 'Mr. Pitiful' (Stax, 1964) and Stockhausen in particular were already fiercely competitive, and when in 'Respect'(Stax, 1965) 1960 Steinecke had assigned direction of the Darmstadt composition course Simón and Garfunkel. 'A Simple Desultory Philippic' (Columbia, 1967) to Boulez, Stockhausen had pointedly stayed away.1 Cage's work and sig- Sinatra, Frank. In the Wee SmallHoun (Capítol, 1954) Songsfor Swinging Lovers (Capítol, 1955) nificance was a constant source of acrimonious debate, and Nono's bitter Surfaris. 'Wipe Out' (Decca, 1963) opposition to himz was one reason for the Italian composer being marginal- The Temptations. 'Papa Was a Rolling Stone' (Motown, 1972) ized by the Cologne inner circle as a structuralist reactionary. -

Russian Museums Visit More Than 80 Million Visitors, 1/3 of Who Are Visitors Under 18

Moscow 4 There are more than 3000 museums (and about 72 000 museum workers) in Russian Moscow region 92 Federation, not including school and company museums. Every year Russian museums visit more than 80 million visitors, 1/3 of who are visitors under 18 There are about 650 individual and institutional members in ICOM Russia. During two last St. Petersburg 117 years ICOM Russia membership was rapidly increasing more than 20% (or about 100 new members) a year Northwestern region 160 You will find the information aboutICOM Russia members in this book. All members (individual and institutional) are divided in two big groups – Museums which are institutional members of ICOM or are represented by individual members and Organizations. All the museums in this book are distributed by regional principle. Organizations are structured in profile groups Central region 192 Volga river region 224 Many thanks to all the museums who offered their help and assistance in the making of this collection South of Russia 258 Special thanks to Urals 270 Museum creation and consulting Culture heritage security in Russia with 3M(tm)Novec(tm)1230 Siberia and Far East 284 © ICOM Russia, 2012 Organizations 322 © K. Novokhatko, A. Gnedovsky, N. Kazantseva, O. Guzewska – compiling, translation, editing, 2012 [email protected] www.icom.org.ru © Leo Tolstoy museum-estate “Yasnaya Polyana”, design, 2012 Moscow MOSCOW A. N. SCRiAbiN MEMORiAl Capital of Russia. Major political, economic, cultural, scientific, religious, financial, educational, and transportation center of Russia and the continent MUSEUM Highlights: First reference to Moscow dates from 1147 when Moscow was already a pretty big town. -

Teaching Post-Tonal Music to Twenty-First- Century Students Author(S): Miguel A

Department of Music Theory, Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University A Pedagogical and Psychological Challenge: Teaching Post-Tonal Music to Twenty-First- Century Students Author(s): Miguel A. Roig-Francolí Source: Indiana Theory Review, Vol. 33, No. 1-2 (Summer 2017), pp. 36-68 Published by: Indiana University Press on behalf of the Department of Music Theory, Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2979/inditheorevi.33.1-2.02 Accessed: 03-09-2018 01:27 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Indiana University Press, Department of Music Theory, Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Indiana Theory Review This content downloaded from 129.74.250.206 on Mon, 03 Sep 2018 01:27:00 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms A Pedagogical and Psychological Challenge: Teaching Post-Tonal Music to Twenty-First-Century Students Miguel A. Roig-Francolí University of Cincinnati ost-tonal music has a pr problem among young musicians, and many not-so-young ones. Anyone who has recently taught a course on the theory and analysis of post-tonal music to a general Pmusic student population mostly made up of performers, be it at the undergraduate or master’s level, will probably immediately understand what the title of this article refers to. -

Renoir, Impressionism, and Full-Length Painting

FIRST COMPREHENSIVE STUDY OF RENOIR’S FULL-LENGTH CANVASES BRINGS TOGETHER ICONIC WORKS FROM EUROPE AND THE U.S. FOR AN EXCLUSIVE NEW YORK CITY EXHIBITION RENOIR, IMPRESSIONISM, AND FULL-LENGTH PAINTING February 7 through May 13, 2012 This winter and spring The Frick Collection presents an exhibition of nine iconic Impressionist paintings by Pierre-Auguste Renoir, offering the first comprehensive study of the artist’s engagement with the full-length format. Its use was associated with the official Paris Salon from the mid-1870s to mid- 1880s, the decade that saw the emergence of a fully fledged Impressionist aesthetic. The project was inspired by Renoir’s La Promenade of 1875–76, the most significant Impressionist work in the Frick’s permanent collection. Intended for public display, the vertical grand-scale canvases in the exhibition are among the artist’s most daring and ambitious presentations of contemporary subjects and are today considered masterpieces of Impressionism. The show and accompanying catalogue draw on contemporary criticism, literature, and archival documents to explore the motivation behind Renoir’s full-length figure paintings as well as their reception by critics, peers, and the public. Recently-undertaken technical studies of the canvases will also shed new light on the artist’s working methods. Works on loan from international institutions are La Parisienne from Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919), Dance at Bougival, 1883, oil on canvas, 71 5/8 x 38 5/8 inches, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Picture Fund; photo: © 2012 Museum the National Museum Wales, Cardiff; The Umbrellas (Les Parapluies) from The of Fine Arts, Boston National Gallery, London (first time since 1886 on view in the United States); and Dance in the City and Dance in the Country from the Musée d’Orsay, Paris. -

PDF Transition

! ! ! ! “FINGERS GLITTERING ABOVE A KEYBOARD:” ! THE KEYBOARD WORKS AND HYBRID CREATIVE PRACTICES OF ! TRISTAN PERICH! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! A Dissertation! Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School! of Cornell University! in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of! Doctor of Musical! Arts! ! ! by! David Benjamin Friend! May 2019! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! © 2019 David Benjamin! Friend! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! “FINGERS GLITTERING ABOVE A KEYBOARD:”! THE KEYBOARD WORKS AND HYBRID CREATIVE PRACTICES OF ! TRISTAN! PERICH! ! David Benjamin Friend, D.M.A.! Cornell University,! 2019! ! !This dissertation examines the life and work of Tristan Perich, with a focus on his works for keyboard instruments. Developing an understanding of his creative practices and a familiarity with his aesthetic entails both a review of his personal narrative as well as its intersection with relevant musical, cultural, technological, and generational discourses. This study examines relevant groupings in music, art, and technology articulated to Perich and his body of work including dorkbot and the New Music Community, a term established to describe the generationally-inflected structural shifts! in the field of contemporary music that emerged in New York City in the first several years of the twenty-first century. Perich’s one-bit electronics practice is explored, and its impact on his musical and artistic work is traced across multiple disciplines and a number of aesthetic, theoretical, and technical parameters. This dissertation also substantiates the centrality of the piano to Perich’s compositional process and to his broader aesthetic cosmology. A selection of his works for keyboard instruments are analyzed, and his unique approach to keyboard technique is contextualized in relation to traditional Minimalist piano techniques and his one-bit electronics practice." ! ! BIOGRAPHICAL! SKETCH! ! !! !David Friend (b.