The Guardian.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

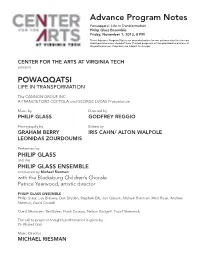

Advance Program Notes Powaqqatsi: Life in Transformation Philip Glass Ensemble Friday, November 1, 2013, 8 PM

Advance Program Notes Powaqqatsi: Life in Transformation Philip Glass Ensemble Friday, November 1, 2013, 8 PM These Advance Program Notes are provided online for our patrons who like to read about performances ahead of time. Printed programs will be provided to patrons at the performances. Programs are subject to change. CENTER FOR THE ARTS AT VIRGINIA TECH presents POWAQQATSI LIFE IN TRANSFORMATION The CANNON GROUP INC. A FRANCIS FORD COPPOLA and GEORGE LUCAS Presentation Music by Directed by PHILIP GLASS GODFREY REGGIO Photography by Edited by GRAHAM BERRY IRIS CAHN/ ALTON WALPOLE LEONIDAS ZOURDOUMIS Performed by PHILIP GLASS and the PHILIP GLASS ENSEMBLE conducted by Michael Riesman with the Blacksburg Children’s Chorale Patrice Yearwood, artistic director PHILIP GLASS ENSEMBLE Philip Glass, Lisa Bielawa, Dan Dryden, Stephen Erb, Jon Gibson, Michael Riesman, Mick Rossi, Andrew Sterman, David Crowell Guest Musicians: Ted Baker, Frank Cassara, Nelson Padgett, Yousif Sheronick The call to prayer in tonight’s performance is given by Dr. Khaled Gad Music Director MICHAEL RIESMAN Sound Design by Kurt Munkacsi Film Executive Producers MENAHEM GOLAN and YORAM GLOBUS Film Produced by MEL LAWRENCE, GODFREY REGGIO and LAWRENCE TAUB Production Management POMEGRANATE ARTS Linda Brumbach, Producer POWAQQATSI runs approximately 102 minutes and will be performed without intermission. SUBJECT TO CHANGE PO-WAQ-QA-TSI (from the Hopi language, powaq sorcerer + qatsi life) n. an entity, a way of life, that consumes the life forces of other beings in order to further its own life. POWAQQATSI is the second part of the Godfrey Reggio/Philip Glass QATSI TRILOGY. With a more global view than KOYAANISQATSI, Reggio and Glass’ first collaboration, POWAQQATSI, examines life on our planet, focusing on the negative transformation of land-based, human- scale societies into technologically driven, urban clones. -

The Philip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966-1976 David Allen Chapman Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) Spring 4-27-2013 Collaboration, Presence, and Community: The Philip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966-1976 David Allen Chapman Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Chapman, David Allen, "Collaboration, Presence, and Community: The hiP lip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966-1976" (2013). All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). 1098. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/1098 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of Music Dissertation Examination Committee: Peter Schmelz, Chair Patrick Burke Pannill Camp Mary-Jean Cowell Craig Monson Paul Steinbeck Collaboration, Presence, and Community: The Philip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966–1976 by David Allen Chapman, Jr. A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2013 St. Louis, Missouri © Copyright 2013 by David Allen Chapman, Jr. All rights reserved. CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES .................................................................................................................... -

Modern Art Music Terms

Modern Art Music Terms Aria: A lyrical type of singing with a steady beat, accompanied by orchestra; a songful monologue or duet in an opera or other dramatic vocal work. Atonality: In modern music, the absence (intentional avoidance) of a tonal center. Avant Garde: (French for "at the forefront") Modern music that is on the cutting edge of innovation.. Counterpoint: Combining two or more independent melodies to make an intricate polyphonic texture. Form: The musical design or shape of a movement or complete work. Expressionism: A style in modern painting and music that projects the inner fear or turmoil of the artist, using abrasive colors/sounds and distortions (begun in music by Schoenberg, Webern and Berg). Impressionism: A term borrowed from 19th-century French art (Claude Monet) to loosely describe early 20th- century French music that focuses on blurred atmosphere and suggestion. Debussy "Nuages" from Trois Nocturnes (1899) Indeterminacy: (also called "Chance Music") A generic term applied to any situation where the performer is given freedom from a composer's notational prescription (when some aspect of the piece is left to chance or the choices of the performer). Metric Modulation: A technique used by Elliott Carter and others to precisely change tempo by using a note value in the original tempo as a metrical time-pivot into the new tempo. Carter String Quartet No. 5 (1995) Minimalism: An avant garde compositional approach that reiterates and slowly transforms small musical motives to create expansive and mesmerizing works. Glass Glassworks (1982); other minimalist composers are Steve Reich and John Adams. Neo-Classicism: Modern music that uses Classic gestures or forms (such as Theme and Variation Form, Rondo Form, Sonata Form, etc.) but still has modern harmonies and instrumentation. -

It's Not That People Don't Like Classical Music. It's That They Don't

“It’s not that people don’t like classical music. It’s that they don’t have the chance to understand and to experience it.” Graphic: Helen Schrayer “It’s not that people don’t like classical music. It’s that they don’t have the chance to understand and to experience it.” – Gustavo Dudamel, Music Director, Los Angeles Philharmonic Mozart. Beethoven. Bach. These are names you’ve probably heard orchestra students say in the halls, but do you really know anything about the people behind those names? Classical music, which concerns most Western music from 1600 to 1900, is a vast genre but is now enjoyed by only a small minority. Only 2.8 percent of albums sold in 2013 are considered classical music. Critics worldwide have expressed their fears that classical music is on death’s door. Despite all this, classical music still affects your life much more than you know. Almost all music that we listen to today is based on some classical chordal formula. Even the simplest songs have a catchy tune that lines up with a sequence that is pleasant to our ears. Jazz, pop, and especially rock have many classical harmonies that we don’t pick up on while “It’s not that people don’t like classical music. It’s that they don’t have the chance to understand and to experience it.” listening. Artists like Adele and Jonny Greenwood, the lead guitarist for Radiohead, were classically-trained musicians who switched over to other genres of music. For all those students who enjoy jazz, many of your favorite artists, such as Oscar Peterson or Bill Evans, spent much of their childhood playing classical music. -

My Fair Lady – Pp

SEASON Book and Lyrics by ALAN JAY LERNER Music by FREDERICK LOEWE Adapted from George Bernard Shaw’s play and Gabriel Pascal’s motion picture Pygmalion LYRIC OPERA OF CHICAGO Table of Contents MARIE-NOËLLE ROBERT / THÉÂTRE DU CHÂTELET IN THIS ISSUE My Fair Lady – pp. 23-43 6 From the General Director 12 2017/18 – Season of Delight, 32 Musical Notes and Chairman Season of Discovery 35 Director’s Note 8 17 Board of Directors Tonight’s Performance 36 After the Curtain Falls 9 19 Women’s Board/Guild Board/Chapters’ Cast 38 Aria Society Executive Board/Young Professionals/ 20 Synopsis Ryan Opera Center Board 47 Breaking New Ground 21 Musical Numbers/Orchestra 10 Administration/Administrative Staff/ 48 Look to the Future 22 Production and Technical Staff Artist Profiles 49 Major Contributors – Special Events and Project Support ALL ABOUT LYRIC’S 2017-18 SEASON pp. 14-20 51 Lyric Unlimited Contributors 53 Ryan Opera Center Contributors 54 Planned Giving: The Overture Society 55 Commemorative Gifts 56 Corporate Partnerships 57 Matching Gifts, Special Thanks and Acknowledgements REED HUMMEL/NASHVILLE OPERA 58 Annual Individual and Foundation Support 64 Facilities and Services/Theater Staff 2 | April - May, 2017 LYRIC OPERA OF CHICAGO www.performancemedia.us | 847-770-4620 3453 Commercial Avenue, Northbrook, IL 60062 Gail McGrath Publisher & President Sheldon Levin Publisher & Director of Finance A. J. Levin Director of Operations Executive Editor Account Managers Lisa Middleton Rand Brichta - Arnie Hoffman - Greg Pigott Southeast Michael Hedge 847-770-4643 Editor Southwest Betsy Gugick & Associates 972-387-1347 Roger Pines East Coast Manzo Media Group 610-527-7047 Associate Editor Marketing and Sales Consultant David L. -

A Cross-Cultural Exploration of Timbre and Texture Through American Minimalism and French Spectralism

Delicateness and Freedom in composition: A cross-cultural exploration of timbre and texture through American minimalism and French spectralism An exegesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree MASTER OF RESEARCH By Emma Harlock SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES AND COMMUNICATIONS ARTS WESTERN SYDNEY UNIVERSITY 2019 Acknowledgements I would like to thank Dr. Bruce Crossman, who has been my supervisor since the first day of the Master of Research, for supporting me and offering your generous guidance throughout both years, and without whom this project would not have taken shape. I would also like to thank Dr. Clare Maclean, who has also offered her kind and generous support and mentorship throughout. Both of my supervisors have contributed greatly to my academic and creative growth, and I am indebted to them for every ounce of kind mentorship they have offered throughout this degree. I also want to thank Dr. Sally Macarthur for her support throughout the Master of Research. I would also like thank my compositional mentor and friend Dr. Holly Harrison, who has provided support throughout this degree, and without whom this project would never have begun. For allowing me to bounce technical ideas off constantly, I would like to thank Senior Technical Officers Mitchell Hart and Noel Burgess. And finally, my family. My parents, Cathy and Peter, who have also provided support throughout this degree, and who have listened throughout the past two years without judgement. Especially to my Nan, Janine Mizzi, who has pushed me to continue postgraduate research since I began at Western Sydney University. -

Model Music Curriculum: Key Stages 1 to 3 Non-Statutory Guidance for the National Curriculum in England

Model Music Curriculum: Key Stages 1 to 3 Non-statutory guidance for the national curriculum in England March 2021 Foreword If it hadn’t been for the classical music played before assemblies at my primary school or the years spent in school and church choirs, I doubt that the joy I experience listening to a wide variety of music would have gone much beyond my favourite songs in the UK Top 40. I would have heard the wonderful melodies of Carole King, Elton John and Lennon & McCartney, but would have missed out on the beauty of Handel, Beethoven and Bach, the dexterity of Scott Joplin, the haunting melody of Clara Schumann’s Piano Trio in G, evocations of America by Dvořák and Gershwin and the tingling mysticism of Allegri’s Miserere. The Model Music Curriculum is designed to introduce the next generation to a broad repertoire of music from the Western Classical tradition, and to the best popular music and music from around the world. This curriculum is built from the experience of schools that already teach a demanding and rich music curriculum, produced by an expert writing team led by ABRSM and informed by a panel of experts – great teachers and musicians alike – and chaired by Veronica Wadley. I would like to thank all involved in producing and contributing to this important resource. It is designed to assist rather than to prescribe, providing a benchmark to help teachers, school leaders and curriculum designers make sure every music lesson is of the highest quality. In setting out a clearly sequenced and ambitious approach to music teaching, this curriculum provides a roadmap to introduce pupils to the delights and disciplines of music, helping them to appreciate and understand the works of the musical giants of the past, while also equipping them with the technical skills and creativity to compose and perform. -

PHILIP GLASS PHILIP GLASS ● Words XXXXXXXX XXXXXXX Cover Words JULIAN DAY

● PHILIP GLASS PHILIP GLASS ● WORDS XXXXXXXX XXXXXXX cover WORDS JULIAN DAY HE ART of GLASS Composer Philip Glass couple of summers ago I was sitting in a hot Brooklyn backyard among musicians from sparked the musical A MATA, a festival for young composers that revolution of minimalism Philip Glass helped set up in the ’90s. As cold drinks were gratefully drained I found myself chatting to a – then pronounced it dead. cheery man who introduced himself as Glass’s tour But, at the age of 75, he is manager. At one point he drew from his back pocket a crumpled sheet of paper that on close inspection still propelled by the manic yielded a long list of cities and dates. energy of those early works, “This,” he declared, “is Phil’s schedule. Right now he ought to be in a cab in Kuala Lumpur heading towards as Julian Day discovered the concert hall. In a few hours’ time he’ll be on a plane to Tokyo. He hits London the following morning then flies on to LA. He plays here in New York next week.” This has been the way of life for Glass for as long as anyone can remember. At 75, an age when many have long retired and hit the golf courses of Florida, he’s on the go as much as ever. Even with the bulge of birthday events already scheduled, 2012 is pretty much business as usual – a constant stream of performances, commissions, collaborations and obligatory chats to the press. It’s almost as if Glass’s early minimalist works – all giddying arpeggios and whirring electric scales – were somehow just winding him up for a life of perpetual motion, in the studio, on stage, on the road and in the air. -

Rethinking Minimalism: at the Intersection of Music Theory and Art Criticism

Rethinking Minimalism: At the Intersection of Music Theory and Art Criticism Peter Shelley A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2013 Reading Committee Jonathan Bernard, Chair Áine Heneghan Judy Tsou Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Music Theory ©Copyright 2013 Peter Shelley University of Washington Abstract Rethinking Minimalism: At the Intersection of Music Theory and Art Criticism Peter James Shelley Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Dr. Jonathan Bernard Music Theory By now most scholars are fairly sure of what minimalism is. Even if they may be reluctant to offer a precise theory, and even if they may distrust canon formation, members of the informed public have a clear idea of who the central canonical minimalist composers were or are. Sitting front and center are always four white male Americans: La Monte Young, Terry Riley, Steve Reich, and Philip Glass. This dissertation negotiates with this received wisdom, challenging the stylistic coherence among these composers implied by the term minimalism and scrutinizing the presumed neutrality of their music. This dissertation is based in the acceptance of the aesthetic similarities between minimalist sculpture and music. Michael Fried’s essay “Art and Objecthood,” which occupies a central role in the history of minimalist sculptural criticism, serves as the point of departure for three excursions into minimalist music. The first excursion deals with the question of time in minimalism, arguing that, contrary to received wisdom, minimalist music is not always well understood as static or, in Jonathan Kramer’s terminology, vertical. The second excursion addresses anthropomorphism in minimalist music, borrowing from Fried’s concept of (bodily) presence. -

Percussion Primer / Tambourine by Neil Grover SELECTION

Neil Grover is a world-renowned percussionist, innovative instrument designer and successful entrepreneur. Neil started his professional career as Principal Percussionist for seven years with the Opera Company of Boston. Since that time he has played with the Royal Ballet of England, Boston Musica Viva, Boston Ballet, American Ballet Theatre, Bolshoi Ballet, Boston Symphony Chamber Players, Boston Symphony and for over 30 years as a percussionist with the Boston Pops. Most recently, Neil toured North America with “Star Wars In Concert”, a musical extravaganza featuring the music of John Williams. Neil has been seen in the hit movie Blown Away and on an MTV video with rock group Aerosmith. He has recorded with the Boston Symphony, Boston Pops, Philip Glass Ensemble, Aerosmith, Empire Brass, Old South Brass and Music from Marlboro. Neil can be heard on John Williams’ soundtrack for the movie Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom and Philip Glass’ “Mishima.” In addition to world-wide tours with the Boston Pops, Neil has toured the U.S. with the Music from Marlboro chamber series, Boston Symphony Chamber Players, and as mallet soloist with the Broadway production of Pirates of Penzance. Grover is also a prolific clinician having appeared at PASIC six times, as well as in Europe, Asia and at top universities across the U.S. He is the author of Four Mallet Primer and co-author (with Garwood Whaley) of Triangle, Tambourine and Cymbal Technique, both published by Meredith Music. Neil has had articles published in leading music journals including Percussive Notes, SBO and Drum Tracks. Neil is the Founder and President of Grover Pro Percussion, one of the world’s most recognized percussion manufacturers. -

Chatter Presents Philip Glass Ensemble Pieces

A PHILIP GLASS MINI-FEST IN 2 PARTS PART 1 ENSEMBLES ~ MON · MAR 14, 2011 · KELLER HALL PART 2 SOLO PIANO ~ TUE · MAR 15, 2011 · SIMMS AUDITORIUM PART 1 · ENSEMBLES Chatter Violin 1 · Megan Holland ~ Kathie Jarrett ~ Debra Terry ~ Steve Ognacevic ~ Barbara Morris Violin 2 · Carol Swift-Matton ~ Justin Pollak ~ Valerie Turner ~ Renee Hemsing Viola · Kim Fredenburgh ~ Ikuko Kanda ~ Cherokee Randolph ~ Lisa DiCarlo Cello · Dana Winograd ~ James Holland ~ Lisa Collins Bass · Jean-Luc Matton ~ Terry Pruitt David Felberg Conductor Albuquerque Youth Symphony Program Violin 1 · Brian Wade ~ Andrew Lin ~ Rachel Schleisinger ~ Maggie Mulkern Violin 2 · Rachel Gallegos ~ Donna Bacon ~ Mirinisa Stewart-Tango Viola · Kelsey Georgeson ~ Maia Scarpetta ~ Thomas Chavez ~ Maggie Jensen ~ Laura Steiner ~ Alex Rubin Cello · Briana Reed ~ Emma Johnson ~ Jonathan Lee ~ Kayla Mathis ~ Maris Daugherty ~ Johnny Mok ~ Dylan Reams Bass · Ben Metzner ~ Sam Brown ~ Evan Davenport ~ Akeylah Corbett Gabriel Gordon Conductor Philip Glass Symphony No 3 for Strings (1995) Chatter plays Movements I through IV without pause ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ SEVEN-MINUTE PAUSE ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ A SIDE-BY-SIDE PERFORMANCE ~ CHATTER AND THE ALBUQUERQUE YOUTH SYMPHONY PROGRAM Philip Glass String Quartet No 2 ‘Company’ (1984) Parts I through IV Samuel Barber Adagio for Strings (1938) ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ SEVEN-MINUTE PAUSE ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ Philip Glass Glassworks (1981) Ikuko Kanda Viola ~ James Holland Cello Valerie Potter | Jesse Tatum Flute ~ James T Shields Clarinet Ashley Kelly | Jamie Schippers Soprano saxophone ~ Jennifer Macke | Matt Harris Tenor Saxophone Peter Ulffers | Nathan Ukens French horn ~ Conor Hanick Piano Movements: Opening ~ Floe ~ Island ~ Rubric ~ Façades ~ Closing This performance is made possible in part by grants from About Philip Glass Boulanger (who also taught Aaron Copland , Virgil Thomson and Quincy Jones) and worked closely with the sitar virtuoso Through his operas, his symphonies, his compositions for and composer Ravi Shankar. -

Transcendental Oscillations in Popular and Classical Music Since the 1800S

Transcendental Oscillations in Popular and Classical Music Since the 1800s by Maxwell Ramage Department of Music Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Nicholas Stoia, Advisor ___________________________ Philip Rupprecht ___________________________ R. Larry Todd ___________________________ Jacqueline Waeber Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music in the Graduate School of Duke University 2021 ABSTRACT Transcendental Oscillations in Popular and Classical Music Since the 1800s by Maxwell Ramage Department of Music Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Nicholas Stoia, Advisor ___________________________ Philip Rupprecht ___________________________ R. Larry Todd ___________________________ Jacqueline Waeber An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music in the Graduate School of Duke University 2021 Copyright by Maxwell Ramage 2021 Abstract In music both popular and classical since the nineteenth century, one finds everywhere chord progressions that alternate between two harmonies in ways that deviate from conventional “textbook” tonality. This thesis aims to answer the following questions: are there meaningful generalizations to be made about these progressions? What is their role in music history? Why have they been so popular with composers of the past two centuries?