Servicing Commandos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LESSON 3 Significant Aircraft of World War II

LESSON 3 Significant Aircraft of World War II ORREST LEE “WOODY” VOSLER of Lyndonville, Quick Write New York, was a radio operator and gunner during F World War ll. He was the second enlisted member of the Army Air Forces to receive the Medal of Honor. Staff Sergeant Vosler was assigned to a bomb group Time and time again we read about heroic acts based in England. On 20 December 1943, fl ying on his accomplished by military fourth combat mission over Bremen, Germany, Vosler’s servicemen and women B-17 was hit by anti-aircraft fi re, severely damaging it during wartime. After reading the story about and forcing it out of formation. Staff Sergeant Vosler, name Vosler was severely wounded in his legs and thighs three things he did to help his crew survive, which by a mortar shell exploding in the radio compartment. earned him the Medal With the tail end of the aircraft destroyed and the tail of Honor. gunner wounded in critical condition, Vosler stepped up and manned the guns. Without a man on the rear guns, the aircraft would have been defenseless against German fi ghters attacking from that direction. Learn About While providing cover fi re from the tail gun, Vosler was • the development of struck in the chest and face. Metal shrapnel was lodged bombers during the war into both of his eyes, impairing his vision. Able only to • the development of see indistinct shapes and blurs, Vosler never left his post fi ghters during the war and continued to fi re. -

D0371 Extract.Pdf

CONTENTS PAGE PREFACE TO FIRST EDITION. IX PREFACE TO SIXTH EDITION le PART 1. SUPERSONIC AND HIGH-ALTITUDE FLYING 3 Introductory survey of the problems of flight in the transonic and supersonic regions. Constitu- tion of atmosphere. Pressure, density, tempera- ture effects. Speed of sound. Mach numbers. Fastest flights. Air compressibility. Sound waves and shock waves. Stability and control at high speed. High-altitude flying. Sonic ceiling. Sonic "bangs" and their potentialities as a weapon of warfare. 2. DESIGN FOR SPEED 25 (1) ENGINES Limitations of piston engine and airscrew. Theory and development of jet propulsion. Thrust augmentation. Turbo-jet. Turbo-prop. Rocket. Ram-jet. Fuels and fuel mixtures. Problems of fuel storage, handling, and safety. Review of selection of engines embodying different principles. (n) AIRCRAFI' Aerodynamics with particular reference to super sonic flight. Evolution of modern aircraft design. Reducing drag, delaying compressibility effects. Wing shapes: straight, swept-back, delta, crescent, v vi CONTENTS PAGE aero-isoclinic. Structural stresses. Materials. The plastic wing. Landing at speed. The "rubber deck." Reverse thrust. Vertical take-off and landing. Powered controls. The flying tail. (m) PILOT Physiological effects of high-speed and high altitude flying. Atmosphere. Pressure. Tempera ture. "G". Pressure suits, pressure cabins, G-suits. The problem of heat. Acceleration and centrifugal limitations. Flight testing in the supersonic regions. 3. DESIGN FOR USE 99 The compromise between the ideal theoretical aircraft and practical considerations. The stage by stage design of representative types of modern jet bombers, fighters, and civil airliners. 4. THINGS TO COME 119 Future development in design. Exploration of the upper air and speeds beyond that of sound. -

Reflections and 1Rememb Irancees

DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A Approved for Public Release Distribution IJnlimiter' The U.S. Army Air Forces in World War II REFLECTIONS AND 1REMEMB IRANCEES Veterans of die United States Army Air Forces Reminisce about World War II Edited by William T. Y'Blood, Jacob Neufeld, and Mary Lee Jefferson •9.RCEAIR ueulm PROGRAM 2000 20050429 011 REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved I OMB No. 0704-0188 The public reporting burden for this collection of Information Is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing the burden, to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704-0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. PLEASE DO NOT RETURN YOUR FORM TO THE ABOVE ADDRESS. 1. REPORT DATE (DD-MM-YYYY) 2. REPORT TYPE 3. DATES COVERED (From - To) 2000 na/ 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5a. CONTRACT NUMBER Reflections and Rememberances: Veterans of the US Army Air Forces n/a Reminisce about WWII 5b. GRANT NUMBER n/a 5c. PROGRAM ELEMENT NUMBER n/a 6. AUTHOR(S) 5d. PROJECT NUMBER Y'Blood, William T.; Neufeld, Jacob; and Jefferson, Mary Lee, editors. -

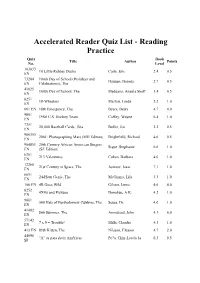

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No. Level 103833 10 Little Rubber Ducks Carle, Eric 2.4 0.5 EN 73204 100th Day of School (Holidays and Haugen, Brenda 2.7 0.5 EN Celebrations), The 41025 100th Day of School, The Medearis, Angela Shelf 1.4 0.5 EN 8251 18-Wheelers Maifair, Linda 5.2 1.0 EN 661 EN 18th Emergency, The Byars, Betsy 4.7 4.0 9801 1980 U.S. Hockey Team Coffey, Wayne 6.4 1.0 EN 7351 20,000 Baseball Cards...Sea Buller, Jon 2.5 0.5 EN 900355 2061: Photographing Mars (MH Edition) Brightfield, Richard 4.6 0.5 EN 904851 20th Century African American Singers Sigue, Stephanie 6.6 1.0 EN (SF Edition) 6201 213 Valentines Cohen, Barbara 4.0 1.0 EN 12260 21st Century in Space, The Asimov, Isaac 7.1 1.0 EN 6651 24-Hour Genie, The McGinnis, Lila 3.3 1.0 EN 166 EN 4B Goes Wild Gilson, Jamie 4.6 4.0 8252 4X4's and Pickups Donahue, A.K. 4.2 1.0 EN 9001 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins, The Seuss, Dr. 4.0 1.0 EN 41482 $66 Summer, The Armistead, John 4.3 6.0 EN 57142 7 x 9 = Trouble! Mills, Claudia 4.3 1.0 EN 413 EN 89th Kitten, The Nilsson, Eleanor 4.7 2.0 44096 "A" es para decir Am?ricas Pe?a, Chin-Lee/de la 6.3 0.5 SP Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No. -

3-VIEWS - TABLE of CONTENTS to Search: Hold "Ctrl" Key Then Press "F" Key

3-VIEWS - TABLE of CONTENTS To search: Hold "Ctrl" key then press "F" key. Enter manufacturer or model number in search box. Click your back key to return to the search page. It is highly recommended to read Order Instructions and Information pages prior to selection. Aircraft MFGs beginning with letter A ................................................................. 3 B ................................................................. 6 C.................................................................10 D.................................................................14 E ................................................................. 17 F ................................................................. 18 G ................................................................21 H................................................................. 23 I .................................................................. 26 J ................................................................. 26 K ................................................................. 27 L ................................................................. 28 M ................................................................30 N................................................................. 35 O ................................................................37 P ................................................................. 38 Q ................................................................40 R................................................................ -

Sir Frank Cooper on Air Force Policy in the 1950S & 1960S

The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society Copyright © Royal Air Force Historical Society, 1993 All rights reserved. 1 Copyright © 1993 by Royal Air Force Historical Society First published in the UK in 1993 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. Printed by Hastings Printing Company Limited Royal Air Force Historical Society 2 THE PROCEEDINGS OFTHE ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY Issue No 11 President: Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Michael Beetham GCB CBE DFC AFC Committee Chairman: Air Marshal Sir Frederick B Sowrey KCB CBE AFC General Secretary: Group Captain J C Ainsworth CEng MRAeS Membership Secretary: Commander P O Montgomery VRD RNR Treasurer: D Goch Esq FCCA Programme Air Vice-Marshal G P Black CB OBE AFC Sub-Committee: Air Vice-Marshal F D G Clark CBE BA Air Commodore J G Greenhill FBIM T C G James CMG MA *Group Captain I Madelin Air Commodore H A Probert MBE MA Group Captain A R Thompson MBE MPhil BA FBIM MIPM Members: A S Bennell Esq MA BLitt *Dr M A Fopp MA PhD FMA FBIM A E Richardson *Group Captain N E Taylor BSc D H Wood Comp RAeS * Ex-officio The General Secretary Regrettably our General Secretary of five years standing, Mr B R Jutsum, has found it necessary to resign from the post and the committee. -

110% Gaming 220 Triathlon Magazine 3D World Adviser

110% Gaming 220 Triathlon Magazine 3D World Adviser Evolution Air Gunner Airgun World Android Advisor Angling Times (UK) Argyllshire Advertiser Asian Art Newspaper Auto Car (UK) Auto Express Aviation Classics BBC Good Food BBC History Magazine BBC Wildlife Magazine BIKE (UK) Belfast Telegraph Berkshire Life Bikes Etc Bird Watching (UK) Blackpool Gazette Bloomberg Businessweek (Europe) Buckinghamshire Life Business Traveller CAR (UK) Campbeltown Courier Canal Boat Car Mechanics (UK) Cardmaking and Papercraft Cheshire Life China Daily European Weekly Classic Bike (UK) Classic Car Weekly (UK) Classic Cars (UK) Classic Dirtbike Classic Ford Classic Motorcycle Mechanics Classic Racer Classic Trial Classics Monthly Closer (UK) Comic Heroes Commando Commando Commando Commando Computer Active (UK) Computer Arts Computer Arts Collection Computer Music Computer Shopper Cornwall Life Corporate Adviser Cotswold Life Country Smallholding Country Walking Magazine (UK) Countryfile Magazine Craftseller Crime Scene Cross Stitch Card Shop Cross Stitch Collection Cross Stitch Crazy Cross Stitch Gold Cross Stitcher Custom PC Cycling Plus Cyclist Daily Express Daily Mail Daily Star Daily Star Sunday Dennis the Menace & Gnasher's Epic Magazine Derbyshire Life Devon Life Digital Camera World Digital Photo (UK) Digital SLR Photography Diva (UK) Doctor Who Adventures Dorset EADT Suffolk EDGE EDP Norfolk Easy Cook Edinburgh Evening News Education in Brazil Empire (UK) Employee -

Aviation Heritage

Group Travel Aviation Heritage Lincolnshire is renowned as the ‘Home of the Royal Air Force’ and has a vast aviation heritage. The county’s flat, open countryside and its location made it ideal for the development of airfields during World War I, and in World War II Lincolnshire became the most important home to Bomber Command. Several airfields are still operational and serving the modern day RAF while former airfields, museums and memorials are witness to the bravery of the men and women who served here in most turbulent times. How to get here The district is well connected from the A1, A15, A17 and A46 roads. Accessibility Please contact individual venues for accessibility requirements. CRANWELL AVIATION HERITAGE MUSEUM ALLOW UP TO: 1.5 hours The Royal Air Force College at Cranwell is a famous landmark in RAF history. A fascinating exhibition recalls in words and photographs the early years of the airfield from its origins as a Royal Naval Air Service Station and the establishment of the College as the first Military Air Academy in the world to its present day operation. Group ticket price Please contact the museum for more information. Parking Free parking is available on site. Guided tours Tours are included within the package; tour group maximum number: 50. Tours can be tailored to specific needs. Please enquire upon booking. Opening Times 1 April to 31 October: 7 days per week, 10am to 4.30pm. 1 November to 31 March: Saturdays and Sundays only, 10am to 4pm. khuyh Contact Details For more information please contact: Cranwell Aviation Heritage Museum Heath Farm, North Rauceby, Sleaford, NG34 8QR Tel: 01529 488490 www.cranwellaviation.co.uk www.heartoflincs.com Page 1 of 6 RAF COLLEGE CRANWELL HERITAGE & ETHOS CENTRE ALLOW UP TO: 1.5 hours RAF College Cranwell Heritage & Ethos Centre contains artefacts and exhibitions covering the Flying Training at RAF Cranwell and the Central Flying School over the last 100 years. -

Finding XH 903 – 33 Squadron's Gloster Javelin at the Jet Age Museum

Finding XH 903 – 33 Squadron’s Gloster Javelin at the Jet Age Museum Gloucestershire Airport, Saturday 4 August 2018 On a very hot Saturday afternoon last weekend, thus the relaxed but appropriate ‘Hart’s Head’ attire worn in some of the following photographs, I paid a visit to the excellent and informative Jet Age Museum at Gloucestershire Airport to investigate the story of the Gloster Javelin bearing 33 Squadron colours that appeared in the recent ‘Loyalty’ newsletter. Accompanied by close friend George Philp, a retired Squadron Leader, my Crewman Leader in Germany while I was on the other squadron, keen aviation buff and a member of the Jet Age Museum, we received a very friendly welcome from the staff at the front desk and all of the guides in the Display Hall, especially as the reason for the visit became apparent. 33 Squadron flew the two seat Javelin, Britain’s first delta wing all-weather fighter, in the Cold War-era between July 1958 and November 1962. The Javelin was equipped with interception radar, had an operational ceiling of 52 000 feet (almost 16 000 metres) and a speed of more than 700 mph (1 130 km/h). Armed with four 30mm cannons and, later, four Firestreak missiles it was built to intercept Russian bombers. Javelin first flew on 26 November 1951 and Gloster and its sister company, Armstrong Whitworth, would go on to build 435 aircraft for the RAF. Unfortunately, the Javelin was the last aircraft type that Gloster would produce and in 1963 the Gloster name disappeared completely from the list of British aircraft manufacturers as a result of the 1957 White Paper on Defence produced by Minister of Defence Duncan Sandys, in which, to counter the growing Soviet ballistic missile threat, he proposed a radical shift away from manned fighter aircraft in favour of missile technology, along with a rationalisation of the British military aircraft and engine industry. -

Sajal Philatelics Cover Auctions Sale No. 261 Thu 16 Aug 2007 1 Lot No

Lot No. Estimate 1924 BRITISH EMPIRE EXHIBITION 1 H.R.Harmer Display FDC with Empire Exhibition Wembley Park slogan. Minor faults, average condition. Cat £350. AT (see photo) £240 2 Plain FDC with Empire Exhibition Wembley Park slogan. Neatly slit open, tiny rust spot at bottom & ink smudge from postmark at bottom of 1d stamp, otherwise very fine fresh cover. Cat £300. AP (see photo) £220 1929 UNIVERSAL POSTAL UNION CONGRESS 3 Plain FDC with T.P.O. CDS. Relevant & rare. Slight ageing in places. UA (see photo) £160 1935 SILVER JUBILEE 4 1d value only on reverse of Silver Jubilee picture postcard with Eltham M/C. AW £80 5 Forgery of Westminster Stamp Co. illustrated FDC with London SW1 CDS. (Cat £550 as genuine). AP (see photo) £30 1937 CORONATION 6 Illustrated FDC with indistinct CDS cancelling the stamp but clear London W1 13th May M/C on reverse. Neatly slit open at top. Cat £20. AT £8 1940 CENTENARY 7 Perkins Bacon FDC with Stamp Centenary (Red Cross) Exhibition London special H/S. Cat £95. AT (see photo) £36 1946 VICTORY 8 Display FDC with Birkenhead slogan "Don't Waste Bread". Cat £75. AT £26 1960 GENERAL LETTER OFFICE 9 with Norwich CDS. Cat £200. AW (see photo) £42 1961 CEPT 10 with Torquay slogan "CEPT European Conference". Cat £15. AT £5 1961 PARLIAMENTARY CONFERENCE 11 Illustrated FDC with London SW1 slogan "Commonwealth Parliamentary Conference". Stamps badly arranged on cover. Cat £75. AT £10 1962 NATIONAL PRODUCTIVITY YEAR 12 (Phosphor) with Cannon Street EC4 CDS. Cat £90. AP (see photo) £50 1963 NATIONAL NATURE WEEK 13 (Phosphor) with Totton, Southampton CDS. -

Library Additions BOOKS

Library Additions BOOKS AERODYNAMICS Distributed by Transatlantic classic first-hand account by South Australia 5031 (https:// UK. 2002. 244pp. Illustrated. Publishers Group, 97 Sir Ross Smith of the epic first www.wakefieldpress.com.au/). ISBN 1-904010-00-8. Flight: and Some of its Greenham Road, London N10 flight to Australia in pursuit of a 2019. 357pp. $29.95 (Aust). Incorporating a number Little Secrets. F M Burrows. 1LN, UK. £116 [20% discount prize of £10,000 – which had ISBN 978-1-74305-663-9. of first-hand recollections, Published by the author, available to RAeS members been announced on 19 March A fictional reconstruction a compilation of concise London. 2017. iv; 322pp. on request; E mark.chaloner@ 1919 by the Australian Prime of the epic first flight to biographies of Air Chief Illustrated. £30. ISBN 978-1- tpgltd.co.uk ] ISBN 978-1- Minister Billy Hughes – for the Australia – the 135 hours 55 Marshal Sir Harry Broadhurst, 79569-651-7. 62410-538-8. first successful Australian- minutes 11,340 mile flight Air Vice-Marshal William Illustrated throughout crewed flight to Australia from of a Vickers Vimy in carefully Crawford-Compton, Squadron with numerous clear colour Both books can also be Great Britain in an aircraft planned stages from England Leader Dave Glaser, Flight diagrams, a well-illustrated purchased as a two-volume made in the British Empire to Australia by Ross and Keith Lieutenant Eric Lock, Flight introduction to the science of set for £165 [20% discount which was to be completed Smith – accompanied by their Lieutenant William ‘Tex’ Ash, fluid dynamics, aerodynamics available to RAeS members within 30 days. -

Canadian Airmen Lost in Wwii by Date 1943

CANADA'S AIR WAR 1945 updated 21/04/08 January 1945 424 Sqn. and 433 Sqn. begin to re-equip with Lancaster B.I & B.III aircraft (RCAF Sqns.). 443 Sqn. begins to re-equip with Spitfire XIV and XIVe aircraft (RCAF Sqns.). Helicopter Training School established in England on Sikorsky Hoverfly I helicopters. One of these aircraft is transferred to the RCAF. An additional 16 PLUTO fuel pipelines are laid under the English Channel to points in France (Oxford). Japanese airstrip at Sandakan, Borneo, is put out of action by Allied bombing. Built with forced labour by some 3,600 Indonesian civilians and 2,400 Australian and British PoWs captured at Singapore (of which only some 1,900 were still alive at this time). It is decided to abandon the airfield. Between January and March the prisoners are force marched in groups to a new location 160 miles away, but most cannot complete the journey due to disease and malnutrition, and are killed by their guards. Only 6 Australian servicemen are found alive from this group at the end of the war, having escaped from the column, and only 3 of these survived to testify against their guards. All the remaining enlisted RAF prisoners of 205 Sqn., captured at Singapore and Indonesia, died in these death marches (Jardine, wikipedia). On the Russian front Soviet and Allied air forces (French, Czechoslovakian, Polish, etc, units flying under Soviet command) on their front with Germany total over 16,000 fighters, bombers, dive bombers and ground attack aircraft (Passingham & Klepacki). During January #2 Flying Instructor School, Pearce, Alberta, closes (http://www.bombercrew.com/BCATP.htm).