Between Fascination and Contempt. Jews And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

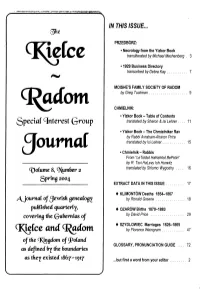

Number 2, Spring 2004

IN THIS ISSUE... PRZEDBÔRZ: • Necrology from the Yizkor Book transliterated by Michael Meshenberg . 3 • 1929 Business Directory transcribed by Debra Kay 7 MOISHE'S FAMILY SOCIETY OF RADOM by Greg Tuckman 9 CHMIELNIK: • Yizkor Book - Table of Contents Speciaf interest Group translated by Sharon & Isi Lehrer.... 11 • Yizkor Book - The Chmielniker Rav by Rabbi Avraham-Aharon Price ^journal translated by Isi Lehrer 15 •Chmielnik-Rabbis From "LeToldot HaKehilot BePolin" by R. Tsvi HaLevy Ish Hurwitz 8, (]>{um6er 2 translated by Shlomo Wygodny 16 gpring 2004 EXTRACT DATA IN THIS ISSUE 17 • KLIMONTÔW Deaths 1854-1867 ^\ journaf oj £Jewish geneafog^ by Ronald Greene 18 puBfishetf quarterly, • OZARÔW Births 1870-1883 covering the (JuBernias oj by David Price 29 ancf • SZYDLOWIEC Marriages 1826-1865 of the ^Kingdom oftpoland by Florence Weingram 47 as defined 6^ the Boundaries GLOSSARY, PRONUNCIATION GUIDE .... 72 as they existed 1867-1917 ...but first a word from your editor 2 Kielce-Radom SIG Journal Volume 8, Number 2 Spring 2004 ... but first a word from our editor In this issue, we have information about the towns of Przedbôrz and Chmielnik. For Przedbôrz - a transliteration of the Special (Interest GrouP names of the Holocaust martyrs from the 1977 Przedbôrz Yizkor Book Przedborz - 33 shanim; and a transcript of the Przedbôrz cjournaf entries from the 1929 Polish Business Directory. ISSN No. 1092-8006 For Chmielnik - a translation of the extensive Table of Contents and a short article from the 1960 Yizkor Book Pinkas Published quarterly, Chmielnik: Yisker bukh noch der Khorev-Gevorener Yidisher in January, April, July and October, by the Kehile; and an article about Chmielnik rabbis translated from KIELCE-RADOM LeToldot HaKehilot BePolin. -

Moses Mendelssohn and the Jewish Historical Clock Disruptive Forces in Judaism of the 18Th Century by Chronologies of Rabbi Families

Moses Mendelssohn and The Jewish Historical Clock Disruptive Forces in Judaism of the 18th Century by Chronologies of Rabbi Families To be given at the Conference of Jewish Genealogy in London 2001 By Michael Honey I have drawn nine diagrams by the method I call The Jewish Historical Clock. The genealogy of the Mendelssohn family is the tenth. I drew this specifically for this conference and talk. The diagram illustrates the intertwining of relationships of Rabbi families over the last 600 years. My own family genealogy is also illustrated. It is centred around the publishing of a Hebrew book 'Megale Amukot al Hatora' which was published in Lvov in 1795. The work of editing this book was done from a library in Brody of R. Efraim Zalman Margaliot. The book has ten testimonials and most of these Rabbis are shown with a green background for ease of identification. The Megale Amukot or Rabbi Nathan Nata Shpiro with his direct descendants in the 17th century are also highlighted with green backgrounds. The numbers shown in the yellow band are the estimated years when the individuals in that generation were born. For those who have not seen the diagrams of The Jewish Historical Clock before, let me briefly explain what they are. The Jewish Historical Clock is a system for drawing family trees ow e-drmanfly 1 I will describe to you the linkage of the Mendelssohn family branch to the network of orthodox rabbis. Moses Mendelssohn 1729-1786 was in his time the greatest Jewish philosopher. He was one of the first Jews to write in a modern language, German and thus opened the doors to Jewish emancipation so desired by the Jewish masses. -

Body Found Andrei Yustschinsky on 20 March (!) 1911 the Body of a Boy

Body found Andrei Yustschinsky On 20 March 096/04/Friday 10h32 Body found Andrei Yustschinsky On 20 March (!) 1911 the body of a boy was found on the border of the urban area of Kiev in a clay pit. It was found in a half-sitting position, the hands were tied together upon the back with a cord. The body was dressed merely with a shirt, underpants, and a single stocking. Behind the head, in a depression in the earthen wall, which according to the record of the then Kiev attorney and high school teacher Gregor Schwartz-Bostunitsch was inscribed with mystical signs, were found five rolled-together school exercise books which bore the name "property of the student of the fore-class, Andrei Yustschinsky, Sophia School"; because of this, the identification was made very shortly. It turned out to be the thirteen-year-old son of the middle-class woman Alexandra Prichodko of Kiev. The Kievskaya Mysl (Kiev Thought) gave the following report at the time about the discovery of the body: "When the body of the unfortunate boy was carried out of the pit, the crowd shuddered, and sobbing could be heard. The aspect of the slain victim was terrible. His face was dark blue and covered with blood, and a several windings of a strong cord, which cut into the skin, were wrapped around the arms. There were three wounds on the head, which all came from some kind of piercing tool. The same wounds were also on the face and on both sides of the neck. -

Lenin-S-Jewish-Question

Lenin’s Jewish Question Lenin’s Jewish Question YOHANAN PETROVSKY-SHTERN New Haven and London Published with assistance from the foundation established in memory of Amasa Stone Mather of the Class of 1907, Yale College. Copyright © 2010 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail [email protected] (U.S. office) or [email protected] (U.K. office). Set in Minion type by Integrated Publishing Solutions. Printed in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Petrovskii-Shtern, Iokhanan. Lenin’s Jewish question / Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-15210-4 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Lenin, Vladimir Il’ich, 1870–1924—Relations with Jews. 2. Lenin, Vladimir Il’ich, 1870–1924—Family. 3. Ul’ianov family. 4. Lenin, Vladimir Il’ich, 1870–1924—Public opinion. 5. Jews— Identity—Case studies. 6. Jewish question. 7.Jews—Soviet Union—Social conditions. 8. Jewish communists—Soviet Union—History. 9. Soviet Union—Politics and government. I. Title. DK254.L46P44 2010 947.084'1092—dc22 2010003985 This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48–1992 (Permanence of Paper). -

Rus Sian Jews Between the Reds and the Whites, 1917– 1920

Rus sian Jews Between the Reds and the Whites, 1917– 1920 —-1 —0 —+1 137-48292_ch00_1P.indd i 8/19/11 8:37 PM JEWISH CULTURE AND CONTEXTS Published in association with the Herbert D. Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies of the University of Pennsylvania David B. Ruderman, Series Editor Advisory Board Richard I. Cohen Moshe Idel Alan Mintz Deborah Dash Moore Ada Rapoport- Albert Michael D. Swartz A complete list of books in the series is available from the publisher. -1— 0— +1— 137-48292_ch00_1P.indd ii 8/19/11 8:37 PM Rus sian Jews Between the Reds and the Whites, 1917– 1920 Oleg Budnitskii Translated by Timothy J. Portice university of pennsylvania press philadelphia —-1 —0 —+1 137-48292_ch00_1P.indd iii 8/19/11 8:37 PM Originally published as Rossiiskie evrei mezhdu krasnymi i belymi, 1917– 1920 (Moscow: ROSSPEN, 2005) Publication of this volume was assisted by a grant from the Lucius N. Littauer Foundation. Copyright © 2012 University of Pennsylvania Press All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher. Published by University of Pennsylvania Press Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104- 4112 www .upenn .edu/ pennpress Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 -1— Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data 0— ISBN 978- 0- 8122- 4364- 2 +1— 137-48292_ch00_1P.indd iv 8/19/11 8:37 PM In memory of my father, Vitaly Danilovich Budnitskii (1930– 1990) —-1 —0 —+1 137-48292_ch00_1P.indd v 8/19/11 8:37 PM -1— 0— +1— 137-48292_ch00_1P.indd vi 8/19/11 8:37 PM contents List of Abbreviations ix Introduction 1 Chapter 1. -

Journal of Religion & Society

Journal of Religion & Society Volume 7 (2005) ISSN 1522-5658 A Kinder, Gentler Teaching of Contempt? Jews and Judaism in Contemporary Protestant Evangelical Children’s Fiction Mark Stover, San Diego State University Abstract This article analyzes contemporary American evangelical children’s fiction with respect to the portrayal of Jews and Judaism. Some of the themes that appear in these novels for children include Jewish religiosity, anti-Semitism, Christian proselytizing, the Holocaust, the Jewishness of Jesus, Jews converting to Christianity, and the implicit emptiness of Jewish spirituality. The author argues that these books, many of which contain conversion narratives, reflect the ambivalence of modern Protestant evangelical Christianity concerning Jews and Judaism. On the one hand, evangelicals respect Jews and condemn all forms of anti-Semitism. On the other hand, evangelicals promote and encourage the conversion of Jews to Christianity through evangelism, which seems to imply a lack of respect or even a subtle contempt for Jewish faith and practice. Introduction [1] Utilizing Jews as major characters in religious Christian fiction written for children is not a new device. A number of children’s stories were written in the nineteenth century depicting Jews who (in the course of the narrative) converted to Christianity (Cutt: 92). Throughout the twentieth century, Jews occasionally appeared in evangelical children’s fiction (Grant; Palmer). Over the years, Jews have also been depicted in fictional settings in Christian Sunday School materials (Rausch 1987). However, the past twelve years have seen a proliferation of evangelical1 Christian novels written for children and young adults that feature Jewish characters. [2] In my research, I examined twenty-nine books published in the United States between 1992 and 2003 that fit this description. -

The Ukrainian Weekly, 2019

INSIDE: UWC leadership meets with Zelenskyy – page 3 Lomachenko adds WBC title to his collection – page 15 Ukrainian Independence Day celebrations – pages 16-17 THEPublished U by theKRAINIAN Ukrainian National Association, Inc., celebrating W its 125th anniversaryEEKLY Vol. LXXXVII No. 36 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 8, 2019 $2.00 Trump considers suspension of military aid Zelenskyy team takes charge to Ukraine, angering U.S. lawmakers as new Rada begins its work RFE/RL delay. Unless, of course, he’s yet again act- ing at the behest of his favorite Russian dic- U.S. President Donald Trump is consid- tator & good friend, Putin,” the Illinois sena- ering blocking $250 million in military aid tor tweeted. to Ukraine, Western media reported, rais- Rep. Adam Kinzinger (R-Ill.), a member of ing objections from lawmakers of both U.S. the House Foreign Affairs Committee, tweet- political parties. ed that “This is unacceptable. It was wrong Citing senior administration officials, when [President Barack] Obama failed to Politico and Reuters reported that Mr. stand up to [Russian President Vladimir] Trump had ordered a reassessment of the Putin in Ukraine, and it’s wrong now.” aid program that Kyiv uses to battle Russia- The administration officials said chances backed separatists in eastern Ukraine. are that the money will be allocated as The review is to “ensure the money is usual but that the determination will not be being used in the best interest of the United made until the review is completed and Mr. States,” Politico said on August 28, and Trump makes a final decision. -

Abstract in the First Years of the Twentieth Century, an Anti-Semitic Document Appeared in Russia That Profoundly Shaped The

Abstract In the first years of the twentieth century, an anti-Semitic document appeared in Russia that profoundly shaped the course of the entire century. Despite being quickly discredited as a plagiarized forgery, The Protocols of the Elders of Zion spread across the world, being translated into dozens of languages and utilized as hateful rhetoric by leaders of many religions and nationalities. While the effects of the document were felt internationally, the Protocols also helped to reshape centuries old prejudices about Jews in a country still in its infancy, Germany. This “hoax of the twentieth century” helped to redefine age-old anti- Semitic values firmly ingrained within German society, and helped Adolf Hitler and his Nazi Party justify committing the landmark genocide of world history, the Holocaust. Utilizing a variety of sources, particularly the actual text of the Protocols and the writings of Adolf Hitler, this examination argues that Hitler and his cabinet became progressively more radicalized towards extermination of the Jews due to their belief in the Jewish world conspiracy outlined within the Protocols. 1 Introduction: Jews in Europe “The weapons in our hands are limitless ambitions, burning greediness, merciless vengeance, hatreds, and malace.”1 This phrase is attributed to a collection of omnipotent Jews supposedly bent on world domination. Collectively called the “Elders of Zion,” this group outlined how it will accomplish its goals of global supremacy in a forged book titled The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. The weapons these Elders claimed to hold were substantial: they asserted control over all aspects of the media and world-banking systems, and maintained their agents had already infiltrated international governments. -

The Transfer Agreement and the Boycott Movement: a Jewish Dilemma on the Eve of the Holocaust

The Transfer Agreement and the Boycott Movement: A Jewish Dilemma on the Eve of the Holocaust Yf’aat Weiss In the summer of 1933, the Jewish Agency for Palestine, the German Zionist Federation, and the German Economics Ministry drafted a plan meant to allow German Jews emigrating to Palestine to retain some of the value of their property in Germany by purchasing German goods for the Yishuv, which would redeem them in Palestine local currency. This scheme, known as the Transfer Agreement or Ha’avarah, met the needs of all interested parties: German Jews, the German economy, and the Mandatory Government and the Yishuv in Palestine. The Transfer Agreement has been the subject of ramified research literature.1 Many Jews were critical of the Agreement from the very outset. The negotiations between the Zionist movement and official representatives of Nazi Germany evoked much wrath. In retrospect, and in view of what we know about the annihilation of European Jewry, these relations between the Zionist movement and Nazi Germany seem especially problematic. Even then, however, the negotiations and the agreement they spawned were profoundly controversial in broad Jewish circles. For this reason, until 1935 the Jewish Agency masked its role in the Agreement and attempted to pass it off as an economic agreement between private parties. One of the German authorities’ principal goals in negotiating with the Zionist movement was to fragment the Jewish boycott of German goods. Although in retrospect we know the boycott had only a marginal effect on German economic 1 Eliahu Ben-Elissar, La Diplomatie du IIIe Reich et les Juifs (1933-1939) (Paris: Julliard, 1969), p. -

Uvic Thesis Template

Fathers, Sons and the Holo-Ghost: Reframing Post-Shoah Male Jewish Identity in Doron Rabinovici’s Suche nach M by Michael Moses Gans BA, Cleveland State University, 1976 MS, University of Massachusetts, 1981 MSW, Barry University, 2008 MA, Central European University, 2009 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Germanic and Slavic Studies Michael Moses Gans, 2012 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Fathers, Sons and the Holo-Ghost: Reframing Post-Shoah Male Jewish Identity in Doron Rabinovici’s Suche nach M by Michael Moses Gans BA, Cleveland State University, 1976 MS, University of Massachusetts, 1981 MSW, Barry University, 2008 MA, Central European University, 2009 Supervisory Committee Dr. Charlotte Schallié, (Department of Germanic and Slavic Studies) Supervisor Dr. Matthew Pollard, (Department of Germanic and Slavic Studies) Departmental Member iii Abstract Supervisory Committee Dr. Charlotte Schallié, (Department of Germanic and Slavic Studies) Supervisor Dr. Matthew Pollard, (Department of Germanic and Slavic Studies) Departmental Member The enduring, mythical and antisemitic figure of Ahasuerus is central to the unraveling and reframing of post-Shoah Jewish identity in Rabinovici’s novel Suche nach M for it serves as the mythological color palette from which Rabinovici draws his characters and, to extend that metaphor, how the Jews have been immortalized in European culture. There is no escape in Suche nach M. When painting the Jew, both Jews and non-Jews can only use brush strokes of color from the Christian-created palette of the mythic, wandering Jew, Ahasuerus, who is stained in the blood of deicide, emasculated, treacherous, and evil. -

Anti-Semitism Through the Centuries

Anti-Semitism through the Centuries First to Third century 50 Jews ordered by Roman Emperor Claudius "not to hold meetings", in the words of Cassius Dio (Roman History, 60.6.6). Claudius later expelled Jews from Rome, according to both Suetonius ("Lives of the Twelve Caesars", Claudius, Section 25.4) and Acts 18:2. 66–73 Great Jewish Revolt against the Romans is crushed by Vespasian and Titus. Titus refuses to accept a wreath of victory, as there is "no merit in vanquishing people forsaken by their own God." (Philostratus, Vita Apollonii). The events of this period were recorded in detail by the Jewish-Roman historian Josephus. His record is largely sympathetic to the Roman view and was written in Rome under Roman protection; hence it is considered a controversial source. Josephus describes the Jewish revolt as being led by "tyrants," to the detriment of the city, and of Titus as having "moderation" in his escalation of the Siege of Jerusalem (70). c. 119 Roman emperor Hadrian bans circumcision, making Judaism de facto illegal. c. 132–135 Crushing of the Bar Kokhba revolt. According to Cassius Dio 580,000 Jews are killed. Hadrian orders the expulsion of Jews from Judea, which is merged with Galilee to form the province Syria Palaestina. Although large Jewish populations remain in Samaria and Galilee, with Tiberias as the headquarters of exiled Jewish patriarchs, this is the start of the Jewish diaspora. Hadrian constructs a pagan temple to Jupiter at the site of the Temple in Jerusalem, builds Aelia Capitolina among ruins of Jerusalem.[4] 167 Earliest known accusation of Jewish deicide (the notion that Jews were held responsible for the death of Jesus) made in a sermon On the Passover attributed to Melito of Sardis. -

Images of the Golem in 20Th Century Austrian Literature

HEIMAT'S SENTRY: IMAGES OF THE GOLEM IN 20TH CENTURY AUSTRIAN LITERATURE A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in German By Jason P. Ager, M.A. Washington, DC December 18, 2012 Copyright 2012 by Jason P. Ager All Rights Reserved ii HEIMAT'S SENTRY: IMAGES OF THE GOLEM IN 20TH CENTURY AUSTRIAN LITERATURE Jason P. Ager, M.A. Thesis Advisor: Peter C. Pfeiffer , Ph.D . ABSTRACT In his collection of essays titled Unheimliche Heimat , W.G. Sebald asserts that, "Es ist offenbar immer noch nicht leicht, sich in Österreich zu Hause zu fühlen, insbesondere wenn einem, wie in den letzten Jahren nicht selten, die Unheimlichkeit der Heimat durch das verschiedentliche Auftreten von Wiedergänger und Vergangenheitsgespenstern öfter als lieb ins Bewußtsein gerufen wird" (Sebald 15-16). Sebald's term "Gespenster" may have a quite literal application; it is unheimlich to note, after all, how often the Golem makes unsettling appearances in twentieth-century Austrian-Jewish literature, each time as a protector and guardian of specific communities under threat. These iterations and reinventions of the Golem tradition give credence to Sebald’s description of Heimat as an ambivalent and often conflicted space, even in a relatively homogenous community, because these portrayals of Heimat juxtapose elements of innocence and guilt, safety and threat, logic and irrationality. In the face of the Holocaust's reign of death and annihilation, it seems fitting that Austrian-Jewish writers reanimated a long- standing symbol of strength rooted in religious tradition to counter destruction and find meaning in chaos and unexampled brutality.