HNA April 12 Cover.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reading 1.2 Caravaggio: the Construction of an Artistic Personality

READING 1.2 CARAVAGGIO: THE CONSTRUCTION OF AN ARTISTIC PERSONALITY David Carrier Source: Carrier, D., 1991. Principles of Art History Writing, University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press, pp.49–79. Copyright ª 1991 by The Pennsylvania State University. Reproduced by permission of the publisher. Compare two accounts of Caravaggio’s personality: Giovanni Bellori’s brief 1672 text and Howard Hibbard’s Caravaggio, published in 1983. Bellori says that Caravaggio, like the ancient sculptor Demetrius, cared more for naturalism than for beauty. Choosing models, not from antique sculpture, but from the passing crowds, he aspired ‘only to the glory of colour.’1 Caravaggio abandoned his early Venetian manner in favor of ‘bold shadows and a great deal of black’ because of ‘his turbulent and contentious nature.’ The artist expressed himself in his work: ‘Caravaggio’s way of working corresponded to his physiognomy and appearance. He had a dark complexion and dark eyes, black hair and eyebrows and this, of course, was reflected in his painting ‘The curse of his too naturalistic style was that ‘soon the value of the beautiful was discounted.’ Some of these claims are hard to take at face value. Surely when Caravaggio composed an altarpiece he did not just look until ‘it happened that he came upon someone in the town who pleased him,’ making ‘no effort to exercise his brain further.’ While we might think that swarthy people look brooding more easily than blonds, we are unlikely to link an artist’s complexion to his style. But if portions of Bellori’s text are alien to us, its structure is understandable. -

Evolution and Ambition in the Career of Jan Lievens (1607-1674)

ABSTRACT Title: EVOLUTION AND AMBITION IN THE CAREER OF JAN LIEVENS (1607-1674) Lloyd DeWitt, Ph.D., 2006 Directed By: Prof. Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr. Department of Art History and Archaeology The Dutch artist Jan Lievens (1607-1674) was viewed by his contemporaries as one of the most important artists of his age. Ambitious and self-confident, Lievens assimilated leading trends from Haarlem, Utrecht and Antwerp into a bold and monumental style that he refined during the late 1620s through close artistic interaction with Rembrandt van Rijn in Leiden, climaxing in a competition for a court commission. Lievens’s early Job on the Dung Heap and Raising of Lazarus demonstrate his careful adaptation of style and iconography to both theological and political conditions of his time. This much-discussed phase of Lievens’s life came to an end in 1631when Rembrandt left Leiden. Around 1631-1632 Lievens was transformed by his encounter with Anthony van Dyck, and his ambition to be a court artist led him to follow Van Dyck to London in the spring of 1632. His output of independent works in London was modest and entirely connected to Van Dyck and the English court, thus Lievens almost certainly worked in Van Dyck’s studio. In 1635, Lievens moved to Antwerp and returned to history painting, executing commissions for the Jesuits, and he also broadened his artistic vocabulary by mastering woodcut prints and landscape paintings. After a short and successful stay in Leiden in 1639, Lievens moved to Amsterdam permanently in 1644, and from 1648 until the end of his career was engaged in a string of important and prestigious civic and princely commissions in which he continued to demonstrate his aptitude for adapting to and assimilating the most current style of his day to his own somber monumentality. -

'Rubens and His Legacy' Exhibition in Focus Guide

Exhibition in Focus This guide is given out free to teachers and full-time students with an exhibition ticket and ID at the Learning Desk and is available to other visitors from the RA Shop at a cost of £5.50 (while stocks last). ‘Rubens I mention in this place, as I think him a remarkable instance of the same An Introduction to the Exhibition mind being seen in all the various parts of the art. […] [T]he facility with which he invented, the richness of his composition, the luxuriant harmony and brilliancy for Teachers and Students of his colouring, so dazzle the eye, that whilst his works continue before us we cannot help thinking that all his deficiencies are fully supplied.’ Sir Joshua Reynolds, Discourse V, 10 December 1772 Introduction Written by Francesca Herrick During his lifetime, the Flemish master Sir Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) For the Learning Department was the most celebrated artist in Europe and could count the English, French © Royal Academy of Arts and Spanish monarchies among his prestigious patrons. Hailed as ‘the prince of painters and painter of princes’, he was also a skilled diplomat, a highly knowledgeable art collector and a canny businessman. Few artists have managed to make such a powerful impact on both their contemporaries and on successive generations, and this exhibition seeks to demonstrate that his Rubens and His Legacy: Van Dyck to Cézanne continued influence has had much to do with the richness of his repertoire. Its Main Galleries themes of poetry, elegance, power, compassion, violence and lust highlight the 24 January – 10 April 2015 diversity of Rubens’s remarkable range and also reflect the main topics that have fired the imagination of his successors over the past four centuries. -

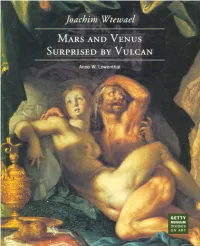

Mars and Venus Surprised by Vulcan

Joachim Wtewael MARS AND VENUS SURPRISED BY VULCAN Joachim Wtewael MARS AND VENUS SURPRISED BY VULCAN Anne W. Lowenthal GETTY MUSEUM STUDIES ON ART Malibu, California Christopher Hudson, Publisher Cover: Mark Greenberg, Managing Editor Joachim Wtewael (Dutch, 1566-1638). Cynthia Newman Bohn, Editor Mars and Venus Surprised by Vulcan, Amy Armstrong, Production Coordinator circa 1606-1610 [detail]. Oil on copper, Jeffrey Cohen, Designer 20.25 x 15.5 cm (8 x 6/8 in.). Malibu, J. Paul Getty Museum (83.PC.274). © 1995 The J. Paul Getty Museum 17985 Pacific Coast Highway Frontispiece: Malibu, California 90265-5799 Joachim Wtewael. Self-Portrait, 1601. Oil on panel, 98 x 74 cm (38^ x 29 in.). Utrecht, Mailing address: Centraal Museum (2264). P.O. Box 2112 Santa Monica, California 90407-2112 All works of art are reproduced (and photographs provided) courtesy of the owners unless otherwise Library of Congress indicated. Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lowenthal, Anne W. Typography by G & S Typesetting, Inc., Joachim Wtewael : Mars and Venus Austin, Texas surprised by Vulcan / Anne W. Lowenthal. Printed by C & C Offset Printing Co., Ltd., p. cm. Hong Kong (Getty Museum studies on art) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-89236-304-5 i. Wtewael, Joachim, 1566-1638. Mars and Venus surprised by Vulcan. 2. Wtewael, Joachim, 1566-1638 — Criticism and inter- pretation. 3. Mars (Roman deity)—Art. 4. Venus (Roman deity)—Art. 5. Vulcan (Roman deity)—Art. I. J. Paul Getty Museum. II. Title. III. Series. ND653. W77A72 1995 759-9492-DC20 94-17632 CIP CONTENTS Telling the Tale i The Historical Niche 26 Variations 47 Vicissitudes 66 Notes 74 Selected Bibliography 81 Acknowledgments 88 TELLING THE TALE The Sun's loves we will relate. -

The Spell of Belgium

The Spell of Belgium By Isabel Anderson THE SPELL OF BELGIUM CHAPTER I THE NEW POST THE winter which I spent in Belgium proved a unique niche in my experience, for it showed me the daily life and characteristics of a people of an old civilization as I could never have known them from casual meetings in the course of ordinary travel. My husband first heard of his nomination as Minister to Belgium over the telephone. We were at Beverly, which was the summer capital that year, when he was told that his name was on the list sent from Washington. Although he had been talked of for the position, still in a way his appointment came as a surprise, and a very pleasant one, too, for we had been assured that “Little Paris” was an attractive post, and that Belgium was especially interesting to diplomats on account of its being the cockpit of Europe. After receiving this first notification, L. called at the “Summer White House” in Beverly, and later went to Washington for instructions. It was not long before we were on our way to the new post. Through a cousin of my husband’s who had married a Belgian, the Comte de Buisseret, we were able to secure a very nice house in Brussels, the Palais d’Assche. As it was being done over by the owners, I remained in Paris during the autumn, waiting until the work should be finished. My husband, of course, went directly to Brussels, and through his letters I was able to gain some idea of what our life there was to be. -

Unequal Lovers: a Study of Unequal Couples in Northern Art

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications and Creative Activity, School of Art, Art History and Design Art, Art History and Design, School of 1978 Unequal Lovers: A Study of Unequal Couples in Northern Art Alison G. Stewart University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/artfacpub Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Stewart, Alison G., "Unequal Lovers: A Study of Unequal Couples in Northern Art" (1978). Faculty Publications and Creative Activity, School of Art, Art History and Design. 19. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/artfacpub/19 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art, Art History and Design, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications and Creative Activity, School of Art, Art History and Design by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Unequal Lovers Unequal Lovers A Study of Unequal Couples in Northern Art A1ison G. Stewart ABARIS BOOKS- NEW YORK Copyright 1977 by Walter L. Strauss International Standard Book Number 0-913870-44-7 Library of Congress Card Number 77-086221 First published 1978 by Abaris Books, Inc. 24 West 40th Street, New York, New York 10018 Printed in the United States of America This book is sold subject to the condition that no portion shall be reproduced in any form or by any means, and that it shall not, by way of trade, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise disposed of without the publisher's consent, in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published. -

MARTEN VAN CLEVE I (C. 1527 – Antwerp – Before 1581) a Wedding

VP4739 MARTEN VAN CLEVE I (c. 1527 – Antwerp – before 1581) A Wedding Procession On canvas, 61¼ X 101 ins. (155.3 X 256 cm) PROVENANCE Marchesa de Bermejillo del Rey, by the early 20th century And by descent to the previous owner Private Collection, Spain, until 2015 LITERATURE M. Diaz Padrón, ‘La Obra de Pedro Brueghel el jóven en Espana”, Archivo Espanol de Arte, 1980, p. 309, fig. 18. K. Ertz, Pieter Brueghel der Jüngere, Lingen, 2000, vol. II, p. 702, no. A830. Against a backdrop of rolling farmlands and a giant windmill, a wedding party makes its way along a road from the village on the right, where preparations are being made for the wedding feast, to the church in the upper left-hand corner. As was customary, the bride and groom walk separately, each processed by a man playing a doedelzac (bagpipes). Tall trees single out the groom, who is identified by the wedding crown he wears on top of his bright red cap. He is followed by two older men, probably the fathers of the bridal couple, and the other menfolk of the village. Then comes the plump and solemn-looking bride, wearing a bridal crown and flanked on either side by pages. She is attended by the two mothers and the other female members of the party. Work in the fields has all but stopped: three sacks of flour sit at the foot of the windmill and a cart stands idle. The workers have all turned out to accompany the wedding procession on its way: among the crowd of well-wishers are young men and old, a shepherd, a miller, his face white with flour, and many more besides. -

Julius S. Held Papers, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3g50355c No online items Finding aid for the Julius S. Held papers, ca. 1921-1999 Isabella Zuralski. Finding aid for the Julius S. Held 990056 1 papers, ca. 1921-1999 Descriptive Summary Title: Julius S. Held papers Date (inclusive): ca. 1918-1999 Number: 990056 Creator/Collector: Held, Julius S (Julius Samuel) Physical Description: 168 box(es)(ca. 70 lin. ft.) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: Research papers of Julius Samuel Held, American art historian renowned for his scholarship in 16th- and 17th-century Dutch and Flemish art, expert on Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Rembrandt. The ca. 70 linear feet of material, dating from the mid-1920s to 1999, includes correspondence, research material for Held's writings and his teaching and lecturing activities, with extensive travel notes. Well documented is Held's advisory role in building the collection of the Museo de Arte de Ponce in Puerto Rico. A significant portion of the ca. 29 linear feet of study photographs documents Flemish and Dutch artists from the 15th to the 17th century. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English Biographical / Historical Note The art historian Julius Samuel Held is considered one of the foremost authorities on the works of Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Rembrandt. -

The Drawings of Cornelis Visscher (1628/9-1658) John Charleton

The Drawings of Cornelis Visscher (1628/9-1658) John Charleton Hawley III Jamaica Plain, MA M.A., History of Art, Institute of Fine Arts – New York University, 2010 B.A., Art History and History, College of William and Mary, 2008 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Art and Architectural History University of Virginia May, 2015 _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................................. i Acknowledgements.......................................................................................................................... ii Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: The Life of Cornelis Visscher .......................................................................................... 3 Early Life and Family .................................................................................................................... 4 Artistic Training and Guild Membership ...................................................................................... 9 Move to Amsterdam ................................................................................................................. -

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice PUBLICATIONS COORDINATION: Dinah Berland EDITING & PRODUCTION COORDINATION: Corinne Lightweaver EDITORIAL CONSULTATION: Jo Hill COVER DESIGN: Jackie Gallagher-Lange PRODUCTION & PRINTING: Allen Press, Inc., Lawrence, Kansas SYMPOSIUM ORGANIZERS: Erma Hermens, Art History Institute of the University of Leiden Marja Peek, Central Research Laboratory for Objects of Art and Science, Amsterdam © 1995 by The J. Paul Getty Trust All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America ISBN 0-89236-322-3 The Getty Conservation Institute is committed to the preservation of cultural heritage worldwide. The Institute seeks to advance scientiRc knowledge and professional practice and to raise public awareness of conservation. Through research, training, documentation, exchange of information, and ReId projects, the Institute addresses issues related to the conservation of museum objects and archival collections, archaeological monuments and sites, and historic bUildings and cities. The Institute is an operating program of the J. Paul Getty Trust. COVER ILLUSTRATION Gherardo Cibo, "Colchico," folio 17r of Herbarium, ca. 1570. Courtesy of the British Library. FRONTISPIECE Detail from Jan Baptiste Collaert, Color Olivi, 1566-1628. After Johannes Stradanus. Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum-Stichting, Amsterdam. Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Historical painting techniques, materials, and studio practice : preprints of a symposium [held at] University of Leiden, the Netherlands, 26-29 June 1995/ edited by Arie Wallert, Erma Hermens, and Marja Peek. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-89236-322-3 (pbk.) 1. Painting-Techniques-Congresses. 2. Artists' materials- -Congresses. 3. Polychromy-Congresses. I. Wallert, Arie, 1950- II. Hermens, Erma, 1958- . III. Peek, Marja, 1961- ND1500.H57 1995 751' .09-dc20 95-9805 CIP Second printing 1996 iv Contents vii Foreword viii Preface 1 Leslie A. -

Webfile121848.Pdf

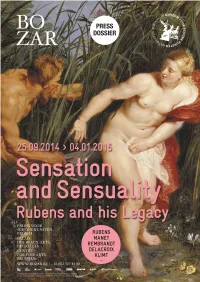

0 TABLE OF CONTENTS Press release ................................................................................................................................................... 2 Catalogue text: Nico Van Hout - Curator ...................................................................................................... 6 Gallery texts ................................................................................................................................................... 11 Transversal Activities ................................................................................................................................... 14 BOZAR MUSIC ......................................................................................................................................... 14 BOZAR LITERATURE ............................................................................................................................. 17 BOZAR EXPO ........................................................................................................................................... 17 BOZAR CINEMA ...................................................................................................................................... 18 Rubens for families ...................................................................................................................................... 19 Disovery trails for families (6>12) ........................................................................................................... 19 -

Statement of Significance

KIRK OF ST NICHOLAS, ABERDEEN Statement of Significance prepared by HISTORY IN THE MAKING HERITAGE CONSULTANTS Aberdeen 2005 Contents Page (1) Introduction 2 (2) History 2 (3) Social significance 4 (4) Location 6 (5) Kirkyard 7 (6) Physical elements: (a) Architecture 7 (b) Archaeology 9 (7) Contents: (a) Historic timber-work and fittings 10 (b) Stained glass 11 (c) Effigies 12 (d) Wall-hangings, paintings 13 (e) Silver plate 14 (f) Organs 15 (g) Bells 15 (8) Documentary background 15 (9) Outline of the Mither Kirk Project 16 (10) Conclusion: summary of significance 17 1 (1) Introduction Although it is only one building, St Nicholas Kirk is a remarkably complex subject for survey. It is a notable ancient monument, which has grown and altered organically from the twelfth century to the present. But it has also been over all these centuries a central spiritual institution of Aberdeen. It therefore requires study, preservation and presentation, plus development in the context of today. The Mither Kirk Project is a broadly based scheme designed to achieve that development on a wide canvas. What follows below is a summary outline of significance, based on the present state of knowledge and research. The term ‘mother church’ (matrix ecclesia in Latin, mither kirk in Scots) was applied to this church in the middle ages. It indicated a church which, though not a cathedral, had superior status, which had other churches or chapels dependent on it and which had the authority to conduct baptisms. St Nicholas has been a significant institution since early times. (2) History The foundation date of the church is unknown, but must lie before 1157 when the first reference to it occurs in a papal document.