Course Outline

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANGELS' SHARE – Ein Schluck Für Die Engel

Kirchen + Kino. DER FILMTIPP 7. Staffel, Oktober 2013 – Mai 2014, 4. Film : „Angels’ Share – Ein Schluck für die Engel “ ANGELS’ SHARE – Ein Schluck für die Engel GB/F/B/I 2012 Länge: 101 Minuten FSK: ab 12 Jahren Originalsprache: Englisch Originaltitel: The Angels’ Share Regie: Ken Loach Drehbuch: Paul Laverty Produktion: Rebecca O’Brien Kamera: Robbie Ryan Schnitt: Jonathan Morris Musik: George Fenton Besetzung: Paul Brannigan (Robbie), John Henshaw (Harry, Sozialarbeiter), Jasmin Riggins (Mo), Gary Maitland (Albert), William Ruane (Rhino), Siobhan Reilly (Leonie, Robbies Freundin), Roger Allam (Thaddeus, Whiskyhändler) Auszeichnungen: Festival de Cannes: „Prix du Jury“ Empfehlung: Von www.medientipp.ch. – Programm-, Film- und Medienhinweise zu Kirche, Religion und Gesellschaft wurde der Film ausgezeichnet als Film des Monats Dezember 2012 mit der Begründung: „Eine bittersüsse Komödie über Robbie, der in eine Familien-Fehde verwickelt ist und alles tut, um sich daraus zu befreien. Als er in der Geburtsabteilung zum ersten Mal den kleinen Luke auf dem Arm hält, ist er ist überwältigt. Der junge Mann schwört, dass seinem Sohn nicht dasselbe Schicksal blühen wird. Mit viel Fantasie und Herzblut begibt sich Robbie auf einen neuen Lebensweg. Statt weiter Gewalt und Rache zu säen, entscheidet er sich für ein neues Hobby: dem Degustieren mit feiner Nase und findigem Gaumen. Die überraschende Hinwendung zum Alkohol – nicht Wein, sondern Malt Whiskey vom Feinsten – eröffnet eine neue berufliche Perspektive. Doch bevor Robbie sein Hobby zur Profession machen kann, muss er in den hohen Norden Schottlands reisen und an einer legendären Whiskey-Verkostung teilnehmen. Dabei begleiten ihn Rhino, Albert und Mo in typischer Kilt-Verkleidung. -

71 Ans De Festival De Cannes Karine VIGNERON

71 ans de Festival de Cannes Titre Auteur Editeur Année Localisation Cote Les Années Cannes Jean Marie Gustave Le Hatier 1987 CTLes (Exclu W 5828 Clézio du prêt) Festival de Cannes : stars et reporters Jean-François Téaldi Ed du ricochet 1995 CTLes (Prêt) W 4-9591 Aux marches du palais : Le Festival de Cannes sous le regard des Ministère de la culture et La 2001 Salle Santeuil 791 (44) Mar sciences sociales de la communication Documentation française Cannes memories 1939-2002 : la grande histoire du Festival : Montreuil Média 2002 Salle Santeuil 791 (44) Can l’album officiel du 55ème anniversaire business & (Exclu du prêt) partners Le festival de Cannes sur la scène internationale Loredana Latil Nouveau monde 2005 Salle Santeuil 791 (44) LAT Cannes Yves Alion L’Harmattan 2007 Magasin W 4-27856 (Exclu du prêt) En haut des marches, le cinéma : vitrine, marché ou dernier refuge Isabelle Danel Scrineo 2007 Salle Santeuil 791 (44) DAN du glamour, à 60 ans le Festival de Cannes brille avec le cinéma Cannes Auguste Traverso Cahiers du 2007 Salle Santeuil 791 (44) Can cinéma (Exclu du prêt) Hollywood in Cannes : The history of a love-hate relationship Christian Jungen Amsterdam 2014 Magasin W 32950 University press Sélection officielle Thierry Frémaux Grasset 2017 Magasin W 32430 Ces années-là : 70 chroniques pour 70 éditions du Festival de Stock 2017 Magasin W 32441 Cannes La Quinzaine des réalisateurs à Cannes : cinéma en liberté (1969- Ed de la 1993 Magasin W 4-8679 1993) Martinière (Exclu du prêt) Cannes, cris et chuchotements Michel Pascal -

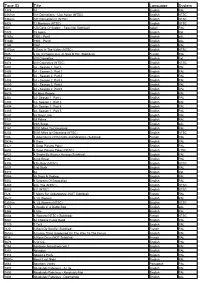

Tape ID Title Language Type System

Tape ID Title Language Type System 1361 10 English 4 PAL 1089D 10 Things I Hate About You (DVD) English 10 DVD 7326D 100 Women (DVD) English 9 DVD KD019 101 Dalmatians (Walt Disney) English 3 PAL 0361sn 101 Dalmatians - Live Action (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 0362sn 101 Dalmatians II (NTSC) English 6 NTSC KD040 101 Dalmations (Live) English 3 PAL KD041 102 Dalmatians English 3 PAL 0665 12 Angry Men English 4 PAL 0044D 12 Angry Men (DVD) English 10 DVD 6826 12 Monkeys (NTSC) English 3 NTSC i031 120 Days Of Sodom - Salo (Not Subtitled) Italian 4 PAL 6016 13 Conversations About One Thing (NTSC) English 1 NTSC 0189DN 13 Going On 30 (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 7080D 13 Going On 30 (DVD) English 9 DVD 0179DN 13 Moons (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 3050D 13th Warrior (DVD) English 10 DVD 6291 13th Warrior (NTSC) English 3 nTSC 5172D 1492 - Conquest Of Paradise (DVD) English 10 DVD 3165D 15 Minutes (DVD) English 10 DVD 6568 15 Minutes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 7122D 16 Years Of Alcohol (DVD) English 9 DVD 1078 18 Again English 4 Pal 5163a 1900 - Part I English 4 pAL 5163b 1900 - Part II English 4 pAL 1244 1941 English 4 PAL 0072DN 1Love (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0141DN 2 Days (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0172sn 2 Days In The Valley (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 3256D 2 Fast 2 Furious (DVD) English 10 DVD 5276D 2 Gs And A Key (DVD) English 4 DVD f085 2 Ou 3 Choses Que Je Sais D Elle (Subtitled) French 4 PAL X059D 20 30 40 (DVD) English 9 DVD 1304 200 Cigarettes English 4 Pal 6474 200 Cigarettes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 3172D 2001 - A Space Odyssey (DVD) English 10 DVD 3032D 2010 - The Year -

Festival Schedule

T H E n OR T HWEST FILM CE n TER / p ORTL a n D a R T M US E U M p RESE n TS 3 3 R D p ortl a n D I n ter n a tio n a L film festi v a L S p O n SORED BY: THE OREGO n I a n / R E G a L C I n EM a S F E BR U a R Y 1 1 – 2 7 , 2 0 1 0 WELCOME Welcome to the Northwest Film Center’s 33rd annual showcase of new world cinema. Like our Northwest Film & Video Festival, which celebrates the unique visions of artists in our community, PIFF seeks to engage, educate, entertain and challenge. We invite you to explore and celebrate not only the art of film, but also the world around you. It is said that film is a universal language—able to transcend geographic, political and cultural boundaries in a singular fashion. In the spirit of Robert Louis Stevenson’s famous observation, “There are no foreign lands. It is the traveler who is foreign,” this year’s films allow us to discover what unites rather than what divides. The Festival also unites our community, bringing together culturally diverse audiences, a remarkable cross-section of cinematic voices, public and private funders of the arts, corporate sponsors and global film industry members. This fabulous ecology makes the event possible, and we wish our credits at the back of the program could better convey our deep appreci- ation of all who help make the Festival happen. -

Women Directors in 'Global' Art Cinema: Negotiating Feminism And

Women Directors in ‘Global’ Art Cinema: Negotiating Feminism and Representation Despoina Mantziari PhD Thesis University of East Anglia School of Film, Television and Media Studies March 2014 “This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution.” Women Directors in Global Art Cinema: Negotiating Feminism and Aesthetics The thesis explores the cultural field of global art cinema as a potential space for the inscription of female authorship and feminist issues. Despite their active involvement in filmmaking, traditionally women directors have not been centralised in scholarship on art cinema. Filmmakers such as Germaine Dulac, Agnès Varda and Sally Potter, for instance, have produced significant cinematic oeuvres but due to the field's continuing phallocentricity, they have not enjoyed the critical acclaim of their male peers. Feminist scholarship has focused mainly on the study of Hollywood and although some scholars have foregrounded the work of female filmmakers in non-Hollywood contexts, the relationship between art cinema and women filmmakers has not been adequately explored. The thesis addresses this gap by focusing on art cinema. It argues that art cinema maintains a precarious balance between two contradictory positions; as a route into filmmaking for women directors allowing for political expressivity, with its emphasis on artistic freedom which creates a space for non-dominant and potentially subversive representations and themes, and as another hostile universe given its more elitist and auteurist orientation. -

Raining Stones Raining Stones

HOMMAGE RAINING STONES RAINING STONES Ken Loach Um seiner Tochter ein Kleid zur Erstkommunion kaufen zu können, Großbritannien 1993 nimmt der arbeitslose Bob jeden Gelegenheitsjob an. Als ihm während 90 Min. · DCP · Farbe des Verkaufs von selbst erjagtem Hammelfleisch der Lieferwagen ge- stohlen wird, bleibt ihm ohnehin keine Wahl: Er reinigt Kloaken, wird Regie Ken Loach als Rausschmeißer schon am ersten Arbeitstag in der Disco verprügelt Buch Jim Allen Kamera Barry Ackroyd und beteiligt sich schließlich gemeinsam mit seinem Kumpel Tommy Schnitt Jonathan Morris an einem Diebstahl von Rasensoden aus dem Klub der Konservativen. Musik Stewart Copeland of SixteenCourtesy Films Wirklich ernst wird Bobs Lage allerdings, als ein Schuldschein in den Mischung Kevin Brazier Besitz des Kredithais Tansey gerät und der brutale Gangster Bobs Frau “Es geht um Menschen, die niedergeknüppelt, Ton Ray Beckett aber nicht gebrochen werden. Das und Tochter gewaltsam bedrängt … Geschickt verbindet RAINING Production Design Martin Johnson Entscheidende an Bob ist, dass er nicht STONES – nach einem Drehbuch von Jim Allen (1926–1999), der selbst Art Director Fergus Clegg untergeht und verzweifelt versucht, seine viele Jahre lang in Middlestone bei Manchester lebte – die Darstellung Kostüm Anne Sinclair Selbstachtung zu bewahren. Außerdem der regionalen wirtschaftlichen Krise unter der Regierung Thatcher mit Maske Louise Fisher behandelt der Film verschiedene Arten von Thriller-Elementen. Dabei lässt Ken Loach (neben burlesken Extempo- Produzentin Sally Hibbin Moral. Es ist nichts Falsches daran, auf dem res) an authentischen Schauplätzen wie einem Nachbarschaftsverein Darsteller Moor ein Schaf zu klauen und es an einen immer wieder Hinweise auf prekäre Wohnsituationen, die ausweglose Metzger zu verkaufen oder Rasensoden von Bruce Jones (Bob Williams) Lage arbeitsloser Jugendlicher und die enge Verbindung von Armut, Julie Brown (Anne Willams) der Rasenbowling-Bahn der Konservativen Verschuldung und Gewalt einfließen. -

Ricerca Film Per Tematica

RICERCA FILM PER TEMATICA 10/2019 TEMATICA TITOLO E COLLOCAZIONE ADOLESCENZA • A tutta velocità – 710. • Amarcord – 564. • Anche libero va bene – 827. • Caterina va in città – 532. • Cielo d’ottobre – 787. • Coach Carter - 1619 • Corpo celeste – 1469. • Così fan tutti – 535. • Cuore selvaggio – 755. • L’albero di Natale – 183. • Detachment, Il distacco – 1554. • Diciassette anni –1261 – 1344. • Edward mani di forbice – 559. • Elephant – 449. • Emporte moi – 943. • Fidati – 197. • Flashdance – 376. • Fratelli d’Italia – 1467. • Fuga dalla scuola media – 107. • Gente comune – 237 – 287 – 446. • Harold e Maude – 399. • Il calamaro e la balena – 981. • Il club degli imperatori – 503 – 1030. • Il diario di Anna Frank – 292 – 528. • Il figlio – 275 – 345 – 840. • Il ladro di bambini – 68 – 152 – 847. • Il laureato – 150. • Il lungo giorno finisce – 57. • Il ribelle – 452 – 641. • Il ritorno – 378. • Il segreto di Esma – 949. • Il sogno di Calvin – 738. • Io ballo da sola – 227 – 450. • J’ai tué ma mère – 1753 - 1765. • Juno – 1303. • Kids – 123. • L’attimo fuggente – 35 – 35a – 269 – 683. • L’India raccontata da James Ivory – 696. • L’occhio del diavolo – 515 – 581. • L’ospite d’inverno – 101 – 102 – 119. • La città dei ragazzi – 308 – 1465. • La classe – 1229 – 1370. • La luna – 804. • La scuola – 55 – 524. • La zona - 1476 • Le ricamatrici – 658. • Lolita – 138. • Luna nera – 708. • Maddalena… zero in condotta – 499 – 1470. • Making off – 1283. • MarPiccolo – 1466. • Mask – 851. • Mean creek – 1126. • Mignon è partita – 597 – 665. • Munyurangabo – 1276. • Niente velo per Jasira – 1358. • No’I Albinoi – 649. • Noi i ragazzi delle zoo di Berlino – 569 – 958. • Non è giusto – 281. -

Narrative Viewpoint and the Representation of Power in George Orwell’S Nineteen Eighty-Four

Narrative viewpoint and the representation of power in George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four BRIGID ROONEY This essay considers how ‘perspective’ and ‘choice of language’ in George Orwell’s novel, Nineteen Eighty-Four, position the reader and contribute to the text’s representation of power, powerplay and people power.1 The aims of this essay can be restated in the form of two key questions. What specific features of the narrative in Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four construct the text’s representation of power, and of powerplay? How do those features position the responder to think and feel about political power and about whether there can be people power? Questions of medium, textual form, and genre It is important to distinguish, at the outset, between ‘narrative’, as a general term for story or the telling of story, and ‘the novel’, as a particular medium or form of narrative. Narratives are everywhere in culture. Not only are they integral to novels but they also permeate films, news reports, and even the everyday stories we use to make sense of life. Narratives always position the listener, reader, or responder in particular ways, expressing partial truths, and creating or constructing certain views of reality while minimizing or excluding others. The novel, on the other hand, is a specific textual form that developed, in the medium of print, during the last three hundred years or so in European societies. Not all cultures and societies have given rise to ‘novels’, though all have told stories, in visual, oral, or written forms. The European novel’s popularity peaked in the nineteenth century. -

Télécharger Au Format

ÉDITO LE FESTIVAL DE TOUS LES CINÉMAS our sa 47e édition, le festival évolue tout en étant fidèle à son identité visuelle très identifiée, grâce aux magnifiques affiches peintes depuis 1991 par Stanislas Bouvier, qui s’est inspiré cette année de Little Big Man. Le festival change de nom. En substituant « Cinéma » à « film », le PFestival La Rochelle Cinéma (FEMA) réaffirme sa singularité et va à l’essentiel. Au-delà du 7e art, le mot cinéma désigne aussi la salle de projection, que nous fréquentons assidûment et que nous nous devons de défendre et de réinventer pour qu’elle demeure le lieu de (re)découverte des films. L’actualité de ces derniers mois nous a prouvé qu’il existe un besoin de se ras- sembler, d’échanger. Quoi de mieux qu’un festival pour se rencontrer ? Quoi de mieux que le cinéma pour déchiffrer l’état du monde ? Les films comme de multiples points de vue sur notre humanité. À commencer par notre film d’ouverture, It Must Be Heaven, dont le titre, quand nous connais- sons l’univers d’Elia Suleiman, paraît bien ironique. Il s’y met en scène avec son dito regard étonné et souvent amusé, dans un monde dévoré par la violence. La force É de son cinéma tient à la composition de ces plans séquences, qui font d’un détail —— tout un symbole. Quand il pose sa caméra place des Victoires à Paris, en direction de la Banque de France devant laquelle défilent lentement des chars de combat, tout est dit. Cette violence, Arthur Penn la dénonçait déjà en 1967 notamment dans Bonnie and Clyde avec la célèbre réplique « we rob banks » (nous dévalisons des banques) et le massacre final filmé au ralenti. -

British Art Cinema

Introduction: British art cinema 1 Introduction – British art cinema: creativity, experimentation and innovation Paul Newland and Brian Hoyle What is art cinema? Definitions of art cinema have long been contested, but the generic term ‘art cinema’ has generally come to stand for feature-length narrative films that are situated at the margins of mainstream cinema, located some- where between overtly experimental films and more obviously commercial product. Whether it is through a modernist, drifting, episodic approach to storytelling; a complex engagement with high culture; the foregrounding of a distinct authorial voice; or a simple refusal to bow to normal commercial considerations, at its heart the term ‘art cinema’ has come to represent film- making which is distinct from – and often in direct opposition to – popular narrative film. But for Steve Neale, writing in a seminal article published in the journal Screen in 1981, the term ‘art cinema’ applies not just to individ- ual films and film histories but also to patterns of distribution, exhibition, reception and audience engagement.1 Moreover, art cinema, in its cultural and aesthetic aspirations but also its audience, relies heavily upon an appeal to ‘universal’ values of culture and art. This is reflected in the existence of international festivals, where distribution is sought for these films, and where their status as ‘art’ – and as films ‘to be taken seriously’ – is confirmed and re-stated through prizes and awards. Writing in 2013, David Andrews argued that art cinema should -

Tape ID Title Language System

Tape ID Title Language System 1375 10 English PAL 0361sn 101 Dalmatians - Live Action (NTSC) English NTSC 0362sn 101 Dalmatians II (NTSC) English NTSC 6826 12 Monkeys (NTSC) English NTSC i031 120 Days Of Sodom - Salo (Not Subtitled) Italian PAL 1078 18 Again English Pal 5163a 1900 - Part I English pAL 5163b 1900 - Part II English pAL 1244 1941 English PAL 0172sn 2 Days In The Valley (NTSC) English NTSC f085 2 Ou 3 Choses Que Je Sais D Elle (Subtitled) French PAL 1304 200 Cigarettes English Pal 6474 200 Cigarettes (NTSC) English NTSC 2401 24 - Season 1, Vol 1 English PAL 2406 24 - Season 2, Part 1 English PAL 2407 24 - Season 2, Part 2 English PAL 2408 24 - Season 2, Part 3 English PAL 2409 24 - Season 2, Part 4 English PAL 2410 24 - Season 2, Part 5 English PAL 5675 24 Hour People English PAL 2402 24- Season 1, Part 2 English PAL 2403 24- Season 1, Part 3 English PAL 2404 24- Season 1, Part 4 English PAL 2405 24- Season 1, Part 5 English PAL 3287 28 Days Later English PAL 5731 29 Palms English PAL 5501 29th Street English pAL 3141 3000 Miles To Graceland English PAL 6234 3000 Miles to Graceland (NTSC) English NTSC f103 4 Adventures Of Reinette and Mirabelle (Subtitled) French PAL 0514s 4 Days English PAL 3421 4 Dogs Playing Poker English PAL 6607 4 Dogs Playing Poker (NTSC) English nTSC g033 4 Shorts By Werner Herzog (Subtitled) English PAL 0160 42nd Street English PAL 6306 4Th Floor (NTSC) English NTSC 3437 51st State English PAL 5310 54 English Pal 0058 55 Days At Peking English PAL 3052 6 Degrees Of Separation English PAL 6389 60s, The (NTSC) English NTSC 6555 61* (NTSC) English NTSC f126 7 Morts Sur Ordonnance (NOT Subtitled) French PAL 5623 8 1/2 Women English PAL 0253sn 8 1/2 Women (NTSC) English NTSC 1175 8 Heads In A Duffel Bag English pAL 5344 8 Mile English PAL 6088 8 Women (NTSC) (Subtitled) French NTSC 5041 84 Charing Cross Road English PAL 1129 9 To 5 English PAL f220 A Bout De Souffle (Subtitled) French PAL 0652s A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum English PAL f018 A Nous Deux (NOT Subtitled) French PAL 3676 A.W.O.L. -

28Th Leeds International Film Festival Presents Leeds Free Cinema Week Experience Cinema in New Ways for Free at Liff 28 from 7 - 13 November

LIFF28th 28 Leeds International Film Festival CONGRATULATIONS TO THE LEEDS INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL IN YOUR 28TH YEAR The BFI is proud to partner with Screen Yorkshire in a fantastic year for filmmaking in the region INCLUDING ‘71 GET SANTA SCREENING AT LIFF28 X + Y CATCH ME DADDY & LIFF28 OPENING NIGHT FILM TESTAMENT OF YOUTH Image: (2014) Testament of Youth James Kent Dir. bfi.org.uk/FilmFund Film Fund Ad LIFF 210x260 2014-10_FINAL 3.indd 1 27/10/2014 11:06 WELCOME From its beginnings at the wonderful, century-old Hyde Park Leeds International Film Festival is a celebration of both Picture House to its status now as a major national film event, film culture and Leeds itself, with this year more than 250 CONGRATULATIONS Leeds International Film Festival has always aimed to bring screenings, events and exhibitions hosted in 16 unique a unique and outstanding selection of global film culture locations across the city. Our venues for LIFF28 include the TO THE LEEDS INTERNATIONAL to the city for everyone to experience. This achievement main hub of Leeds Town Hall, the historic cinemas Hyde is not possible without collaborations and this year we’ve Park Picture House and Cottage Road, other city landmarks FILM FESTIVAL IN YOUR 28TH YEAR assembled our largest ever line-up of partners. From our like City Varieties, The Tetley, Left Bank, and Royal Armouries, long-term major funders the European Union and the British Vue Cinemas at The Light and the Everyman Leeds, in their Film Institute to exciting new additions among our supporting recently-completed Screen 4, and Chapel FM, the new arts The BFI is proud to partner with Screen Yorkshire organisations, including Game Republic, Infiniti, and Trinity centre for East Leeds.