Digital Youth with Disabilities the John D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Physical Therapy Board of California Progress Notes

PROGRESS NOTES PHYSICAL THERAPY BOARD OF CALIFORNIA FALL 2019 INSIDE THIS EDITION President’s Message .......................................................1 Do We Have Your Email Address? ..............................2 Watch for Us .....................................................................3 Stay Connected ................................................................3 Board Members ................................................................3 Executive Staff ..................................................................3 Do You Want to Host a Board Meeting? ....................4 Benefits of Attending a Board Meeting ......................5 What a BreEZe for Consumers .....................................6 Substance Abuse Rehabilitation Hotline .....................6 A Personal Account from a Licensee in Recovery .........7 P.T. Spotlight ......................................................................9 ‘Therapist of Record’ and ‘Hand-Off’ Procedure .......11 Continuing Competency ..............................................13 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE PTBC Milestones .............................................................13 PTBC Outreach Services .............................................14 Changing Seasons Go Green! ........................................................................14 By Alicia Rabena-Amen, Board President Student Presentations Feedback ................................15 Autumn greetings to California consumers, New Physical Therapists ..............................................16 -

Youth with Disabilities in Law and Civil Society: Exclusion and Inclusion in Public Policy and NGO Networks in Cambodia and Indonesia

Disability and the Global South, 2014 OPEN ACCESS Vol.1, No. 1, 5-28 ISSN 2050-7364 www.dgsjournal.org Youth with Disabilities in Law and Civil Society: Exclusion and inclusion in public policy and NGO networks in Cambodia and Indonesia Stephen Meyersa, Valerie Karrb and Victor Pinedac aUniversity of California, San Diego; bUniversity of New Hampshire; cUniversity of California, Berkeley. Corresponding Author- Email: [email protected] Youth with disabilities, as a subgroup of both persons with disabilities and of youth, are often left out of both legislation and advocacy networks. One step towards addressing the needs of youth with disabilities is to look at their inclusion in both the law and civil society in various national contexts. This article, which is descriptive in nature, presents research findings from an analysis of public policy and legislation and qualitative data drawn from interviews, focus group discussions, and site visits conducted on civil society organizations working in Phnom Penh, Cambodia and Jakarta, Indonesia. Data was collected during two separate research visits in the Spring and Summer of 2011 as a part of a larger study measuring youth empowerment. Key findings indicate that youth with disabilities are underrepresented in both mainstream youth and mainstream disability advocacy organizations and networks and are rarely mentioned in either youth or disability laws. This has left young women and men with disabilities in a particularly vulnerable place, often without the means of advancing their interests nor the specification of how new rights or public initiatives should address their transition to adulthood. Keywords: Global South; inclusive development; youth policy; disability policy; Cambodia; Indonesia Introduction The passage of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) in 2006 was a landmark achievement that has since begun to filter down and affect the everyday lives of persons with disabilities around the globe. -

Autism Entangled – Controversies Over Disability, Sexuality, and Gender in Contemporary Culture

Autism Entangled – Controversies over Disability, Sexuality, and Gender in Contemporary Culture Toby Atkinson BA, MA This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Sociology Department, Lancaster University February 2021 1 Declaration I declare that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in substantially the same form for the award of a higher degree elsewhere. Furthermore, I declare that the word count of this thesis, 76940 words, does not exceed the permitted maximum. Toby Atkinson February 2021 2 Acknowledgements I want to thank my supervisors Hannah Morgan, Vicky Singleton, and Adrian Mackenzie for the invaluable support they offered throughout the writing of this thesis. I am grateful as well to Celia Roberts and Debra Ferreday for reading earlier drafts of material featured in several chapters. The research was made possible by financial support from Lancaster University and the Economic and Social Research Council. I also want to thank the countless friends, colleagues, and family members who have supported me during the research process over the last four years. 3 Contents DECLARATION ......................................................................................... 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................. 3 ABSTRACT .............................................................................................. 9 PART ONE: ........................................................................................ -

Download Issue

YOUTH &POLICY No. 116 MAY 2017 Youth & Policy: The final issue? Towards a new format Editorial Group Paula Connaughton, Ruth Gilchrist, Tracey Hodgson, Tony Jeffs, Mark Smith, Jean Spence, Naomi Thompson, Tania de St Croix, Aniela Wenham, Tom Wylie. Associate Editors Priscilla Alderson, Institute of Education, London Sally Baker, The Open University Simon Bradford, Brunel University Judith Bessant, RMIT University, Australia Lesley Buckland, YMCA George Williams College Bob Coles, University of York John Holmes, Newman College, Birmingham Sue Mansfield, University of Dundee Gill Millar, South West Regional Youth Work Adviser Susan Morgan, University of Ulster Jon Ord, University College of St Mark and St John Jenny Pearce, University of Bedfordshire John Pitts, University of Bedfordshire Keith Popple, London South Bank University John Rose, Consultant Kalbir Shukra, Goldsmiths University Tony Taylor, IDYW Joyce Walker, University of Minnesota, USA Anna Whalen, Freelance Consultant Published by Youth & Policy, ‘Burnbrae’, Black Lane, Blaydon Burn, Blaydon on Tyne NE21 6DX. www.youthandpolicy.org Copyright: Youth & Policy The views expressed in the journal remain those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Editorial Group. Whilst every effort is made to check factual information, the Editorial Group is not responsible for errors in the material published in the journal. ii Youth & Policy No. 116 May 2017 About Youth & Policy Youth & Policy Journal was founded in 1982 to offer a critical space for the discussion of youth policy and youth work theory and practice. The editorial group have subsequently expanded activities to include the organisation of related conferences, research and book publication. Regular activities include the bi- annual ‘History of Community and Youth Work’ and the ‘Thinking Seriously’ conferences. -

Normalising the Presence of People with Disabilities in the Fashion Industry

Leggi l'articolo su beautynews Normalising the presence of people with disabilities in the fashion industry NOVEMBER 22nd, 7 pm – 8 pm CET Live on photovoguefestival.vogue.it Embracing gender fluidity, the diversity of bodies and beauty types, regardless of race and ethnic group, is a conquest that is changing the aesthetic standards of our times, thereby proceeding to change people’s cultural and identity codes in terms of inclusivity, openness and dialogue. And yet, much still needs to be done, for instance, with regard to the representation of disability. An issue dear to Photo Vogue Festival and its Artistic Director Alessia Glaviano from its first edition. Glaviano will talk about the changes that we are witnessing in regard to the representation of people with disabilities in the fashion industry with Aaron Philip, the first model with disability to be the face of a major high fashion brand, and Claudia Walder, editor, creative director and disability activist. Talk in English BIOGRAPHIES pagina 1 / 6 Aaron Philip Tyler Mitchell Aaron Philip Aaron Philip refuses to be defined. Hailing from The Bronx by way of the Caribbean nation of Antigua and Barbuda, Aaron was discovered through her social media where she took notice of the lack of representation of trans women of color within the fashion industry, let alone anyone with a disability. Represented by Community New York, she has emerged as a trail-blazer, determined to represent her communities as a model. With a steadfast, sincere approach to her career, Aaron (pronounced A-ron) is driven by the lack of disability representation in the media, specifically in the fashion and beauty realms. -

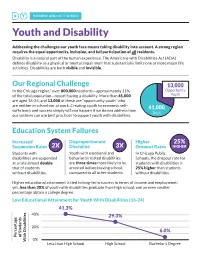

INFORM and ACT SERIES Youth and Disability

INFORM AND ACT SERIES Youth and Disability Addressing the challenges our youth face means taking disability into account. A strong region requires the equal opportunity, inclusion, and full participation of all residents. Disability is a natural part of the human experience. The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) defines disability as a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities. Disabilities are both visible and invisible. Our Regional Challenge 13,000 In the Chicago region,* over 800,000 residents—approximately 11% Opportunity of the total population—report having a disability. More than 41,000 Youth are aged 16-24, and 13,000 of these are “opportunity youth” who are neither in school nor at work. Creating a path to economic self- 41,000 sufficiency and success simply will not happen if we do not address how Total our systems can use best practices to support youth with disabilities. Education System Failures Increased Disproportionate Higher 25% Suspension Rates 2X Discipline 3X Dropout Rates HIGHER Students with Youth with emotional and In Chicago Public disabilities are suspended behavioral related disabilities Schools, the dropout rate for at a rate almost double are three times more likely to be students with disabilities is that of students arrested before leaving school, 25% higher than students without disabilities. compared to all other students. without disabilities. Higher educational attainment is tied to long-term success in terms of income and employment; yet, less than 30% of youth with disabilities graduate from high school, and an even smaller percentage obtain a college degree. Low Educational Attainment for Youth With Disabilities (16-24) 41.3% 40% 29.3% 20% 6.0% Percentage Percentage of Students 0% With Disabilities Less than High School High School Bachelor’s Degree Employment Gaps While mounting evidence demonstrates that hiring this overlooked talent pool can increase productivity and reduce costly turnover, barriers persist both when seeking employment and while on the job. -

Interdisciplinary Disability Studies

YOUTH AND DISABILITY Interdisciplinary Disability Studies Series Editor: Mark Sherry, The University of Toledo, USA Disability studies has made great strides in exploring power and the body. This series extends the interdisciplinary dialogue between disability studies and other fields by asking how disability studies can influence a particular field. It will show how a deep engagement with disability studies changes our understanding of the following fields: sociology, literary studies, gender studies, bioethics, social work, law, education, and history. This ground-breaking series identifies both the practical and theoretical implications of such an interdisciplinary dialogue and challenges people in disability studies as well as other disciplinary fields to critically reflect on their professional praxis in terms of theory, practice, and methods. Other titles in the series Disability, Human Rights and the Limits of Humanitarianism Edited by Michael Gill and Cathy J. Schlund-Vials Disability and Social Movements Australian Perspectives Rachel Carling-Jenkins Forthcoming titles in the series Communication, Sport and Disability The Case of Power Soccer Michael S. Jeffress Disability and Qualitative Inquiry Methods for Rethinking an Ableist World Edited by Ronald J. Berger and Laura S. Lorenz Youth and Disability A Challenge to Mr Reasonable Jenny SlateR Sheffield Hallam University, UK First published 2015 by Ashgate Publishing Published 2016 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business Copyright © 2015 Jenny Slater Jenny Slater has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work. -

Directory of Organisations and Resources for People with Disabilities in South Africa

DISABILITY ALL SORTS A DIRECTORY OF ORGANISATIONS AND RESOURCES FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES IN SOUTH AFRICA University of South Africa CONTENTS FOREWORD ADVOCACY — ALL DISABILITIES ADVOCACY — DISABILITY-SPECIFIC ACCOMMODATION (SUGGESTIONS FOR WORK AND EDUCATION) AIRLINES THAT ACCOMMODATE WHEELCHAIRS ARTS ASSISTANCE AND THERAPY DOGS ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR HIRE ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR PURCHASE ASSISTIVE DEVICES — MAIL ORDER ASSISTIVE DEVICES — REPAIRS ASSISTIVE DEVICES — RESOURCE AND INFORMATION CENTRE BACK SUPPORT BOOKS, DISABILITY GUIDES AND INFORMATION RESOURCES BRAILLE AND AUDIO PRODUCTION BREATHING SUPPORT BUILDING OF RAMPS BURSARIES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — EASTERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — FREE STATE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — GAUTENG CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — KWAZULU-NATAL CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — LIMPOPO CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — MPUMALANGA CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTHERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTH WEST CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — WESTERN CAPE CHARITY/GIFT SHOPS COMMUNITY SERVICE ORGANISATIONS COMPENSATION FOR WORKPLACE INJURIES COMPLEMENTARY THERAPIES CONVERSION OF VEHICLES COUNSELLING CRÈCHES DAY CARE CENTRES — EASTERN CAPE DAY CARE CENTRES — FREE STATE 1 DAY CARE CENTRES — GAUTENG DAY CARE CENTRES — KWAZULU-NATAL DAY CARE CENTRES — LIMPOPO DAY CARE CENTRES — MPUMALANGA DAY CARE CENTRES — WESTERN CAPE DISABILITY EQUITY CONSULTANTS DISABILITY MAGAZINES AND NEWSLETTERS DISABILITY MANAGEMENT DISABILITY SENSITISATION PROJECTS DISABILITY STUDIES DRIVING SCHOOLS E-LEARNING END-OF-LIFE DETERMINATION ENTREPRENEURIAL -

Resources for Working with Youth with Disabilities

ATTACHMENT: Resources for Working with Youth with Disabilities Resources are listed alphabetically: Association for Higher Education and Disability (AHEAD) http://www.ahead.org/ AHEAD is a professional membership organization for individuals involved in the development of policy and the provision of quality services to meet the needs of persons with disabilities involved all areas of higher education. Disability and Employment Workforce3One Web Site https://disability.workforce3one.org (Workforce3 One requires a username and password to access the site. It is free, easy to register, and the access to workforce-related resources and information will be a great benefit to workforce professionals). The purpose of the Disability and Employment Community of Practice is to disseminate promising practices to promote the positive employment outcomes of people with disabilities and expand the capacity of the One- Stop Career Center system to serve customers with disabilities. There is a great deal of information (videos, briefs, promising practices, and other resources) related to the employment of youth with disabilities. This site compiles information related to disability and employment in one location on Workforce3 One, and, along with the addition of a new “Disability” super search category, will make it easier for users to find this information. The disability and employment resources are divided into four main categories. Promising Practices https://disability.workforce3one.org/page/tag/promising_practices This section includes examples of promising practices to expand the capacity of the One-Stop Career Center system to serve customers with disabilities and promote positive employment outcomes of people with disabilities. Access and Accommodations https://disability.workforce3one.org/page/tag/access___accommodations This section provides information and resources on: how to ensure physical, programmatic, and communication access to people with disabilities; the purposes and uses of assistive technology; and how to provide reasonable accommodations. -

TEGL31-10.Pdf

2 3. Background. The U.S. Department of Labor (the Department) is committed to helping all workers obtain “good jobs.” This includes helping to eliminate multiple challenges to employment that youth with disabilities face. In support of this vision, the Employment and Training Administration (ETA) and the Office of Disability Employment Policy (ODEP) believe it is critical to promote improved services to youth with disabilities in the public workforce system. Given the current economic situation, the public workforce system is focusing its resources to meet the extremely high national demand for employment and training services. Although dedicated resources are limited, particularly in these tough economic times, the Department is encouraging the public workforce system to enhance services to youth with disabilities. While the Department acknowledges that the public workforce system currently serves a number of youth with disabilities, the resources and successful strategies included in this guidance can further assist the public workforce system to expand capacity and adopt practices for effectively serving this population. According to the U.S. Department of Education’s National Longitudinal Transition Study, youth with disabilities are less likely to complete high school and are only half as likely to attend post-secondary education as their non-disabled peers. In 2005-2006, the percentage of youth with disabilities exiting school with a regular high school diploma was 57 percent, compared to 87.6 percent of the general student population. During the same time period, 46 percent of youth with disabilities enrolled in post-secondary schools, compared to 63 percent of the general population. Youth with disabilities that are not easily recognized through observation, or that have not been identified through traditional testing within the educational system, may experience difficulty with traditional educational settings or may drop out of school. -

Annual Report 2014 Access, Services and Knowledge (ASK), Youth Empowerment Alliance (YEA)

Annual Report 2014 Access, Services and Knowledge (ASK), Youth Empowerment Alliance (YEA) An exploration of barriers and enabling factors for young people with disabilities to access sexual and reproductive health services in Senegal Final Report Utrecht, March 2016 Authors: Eva Burke, Alex le May, Fatou Kébé & Ilse Flink1 1 Corresponding author: [email protected] © Rutgers 2016 Suggested citation: Burke E., May A. le, Kébé F. & Flink I., 2016 “An exploration of barriers and enabling factors for young people with disabilities to access sexual and reproductive health services in Senegal”, Rutgers The Access, Services and Knowledge (ASK) programme is a three-year programme (from 2013 to 2015) funded by the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs with the aim of improving the SRHR of young people (10 – 24 yrs.), including underserved groups. The programme which is a joint effort of eight organizations comprising of Rutgers (lead), Simavi, Amref Flying Doctors, CHOICE for Youth and Sexuality, dance4life, Stop AIDS Now!, the International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF), and Child Helpline International (CHI) is implemented in 7 countries, namely Ethiopia, Ghana, Indonesia, Kenya, Pakistan, Senegal, and Uganda. Operations research (OR) was identified as an integral part of activities in the ASK programme. The aim was to enhance the performance of the program, improve outcomes, assess feasibility of new strategies and/or assess or improve the programme Theory of Change. Contents Acknowledgements 3 Summary 4 Introduction 6 Objectives 10 Definitions 11 Methodology 12 Results 18 Discussion 33 Recommendations 37 Limitations 40 Conclusions 41 References 43 2 Acknowledgements The research team expresses its appreciation to all individuals and organisations who participated in the study. -

An International Conversation on Disabled Children's Childhoods

This is a repository copy of An international conversation on disabled children’s childhoods: Theory, ethics and methods. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/166727/ Version: Published Version Article: Underwood, K., Moreno-Angarita, M., Curran, T. et al. (2 more authors) (2020) An international conversation on disabled children’s childhoods: Theory, ethics and methods. Canadian Journal of Disability Studies, 9 (5). pp. 302-327. ISSN 1929-9192 10.15353/cjds.v9i5.699 Reuse This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (CC BY-NC-ND) licence. This licence only allows you to download this work and share it with others as long as you credit the authors, but you can’t change the article in any way or use it commercially. More information and the full terms of the licence here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Canadian Journal of Disability Studies Published by the Canadian Disability Studies Association Association Canadienne des Études sur le handicap Hosted by The University of Waterloo www.cjds.uwaterloo An International Conversation on Disabled Children’s Childhoods: Theory, Ethics and Methods Kathryn Underwood Professor, School of Early Childhood Studies, Ryerson University