Young Persons with Disabilities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Youth with Disabilities in Law and Civil Society: Exclusion and Inclusion in Public Policy and NGO Networks in Cambodia and Indonesia

Disability and the Global South, 2014 OPEN ACCESS Vol.1, No. 1, 5-28 ISSN 2050-7364 www.dgsjournal.org Youth with Disabilities in Law and Civil Society: Exclusion and inclusion in public policy and NGO networks in Cambodia and Indonesia Stephen Meyersa, Valerie Karrb and Victor Pinedac aUniversity of California, San Diego; bUniversity of New Hampshire; cUniversity of California, Berkeley. Corresponding Author- Email: [email protected] Youth with disabilities, as a subgroup of both persons with disabilities and of youth, are often left out of both legislation and advocacy networks. One step towards addressing the needs of youth with disabilities is to look at their inclusion in both the law and civil society in various national contexts. This article, which is descriptive in nature, presents research findings from an analysis of public policy and legislation and qualitative data drawn from interviews, focus group discussions, and site visits conducted on civil society organizations working in Phnom Penh, Cambodia and Jakarta, Indonesia. Data was collected during two separate research visits in the Spring and Summer of 2011 as a part of a larger study measuring youth empowerment. Key findings indicate that youth with disabilities are underrepresented in both mainstream youth and mainstream disability advocacy organizations and networks and are rarely mentioned in either youth or disability laws. This has left young women and men with disabilities in a particularly vulnerable place, often without the means of advancing their interests nor the specification of how new rights or public initiatives should address their transition to adulthood. Keywords: Global South; inclusive development; youth policy; disability policy; Cambodia; Indonesia Introduction The passage of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) in 2006 was a landmark achievement that has since begun to filter down and affect the everyday lives of persons with disabilities around the globe. -

JDAIM Lesson Plans 2019

Rabbi Philip Warmflash, Chief Executive Officer Walter Ferst, President The Jewish Special Needs/Disability Inclusion Consortium of Greater Philadelphia Presents Jewish Disability Awareness & Inclusion Month (JDAIM) Lesson Plans Jewish Learning Venture innovates programs that help people live connected Jewish lives. 1 261 Old York Road, Suite 720 / Jenkintown, PA 19046 / 215.320.0360 / jewishlearningventure.org Partners with Jewish Federation of Greater Philadelphia Rabbi Philip Warmflash, Chief Executive Officer Walter Ferst, President INTRODUCTION Jewish Disability Awareness, Acceptance & Inclusion Month (JDAIM) is a unified national initiative during the month of February that aims to raise disability awareness and foster inclusion in Jewish communities worldwide. In the Philadelphia area, the Jewish Special Needs/Disability Inclusion Consortium works to expand opportunities for families of students with disabilities. The Consortium is excited to share these comprehensive lesson plans with schools, youth groups, and early childhood centers in our area. We hope that the children in our classrooms and youth groups will eventually become Jewish leaders and we hope that thinking about disability awareness and inclusion will become a natural part of their Jewish experience. We appreciate you making time for teachers to use these lessons during February—or whenever it’s convenient for you. For additional resources, please email me at gkaplan- [email protected] or call me at 215-320-0376. Thank you to Rabbi Michelle Greenfield for her hard work on this project and to Alanna Raffel for help with editing. Sincerely, Gabrielle Kaplan-Mayer, Director, Whole Community Inclusion NOTES FOR EDUCATORS · We hope that you can make these lessons as inclusive as possible for all kinds of learners and for students with different kinds of disabilities. -

Autism Entangled – Controversies Over Disability, Sexuality, and Gender in Contemporary Culture

Autism Entangled – Controversies over Disability, Sexuality, and Gender in Contemporary Culture Toby Atkinson BA, MA This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Sociology Department, Lancaster University February 2021 1 Declaration I declare that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in substantially the same form for the award of a higher degree elsewhere. Furthermore, I declare that the word count of this thesis, 76940 words, does not exceed the permitted maximum. Toby Atkinson February 2021 2 Acknowledgements I want to thank my supervisors Hannah Morgan, Vicky Singleton, and Adrian Mackenzie for the invaluable support they offered throughout the writing of this thesis. I am grateful as well to Celia Roberts and Debra Ferreday for reading earlier drafts of material featured in several chapters. The research was made possible by financial support from Lancaster University and the Economic and Social Research Council. I also want to thank the countless friends, colleagues, and family members who have supported me during the research process over the last four years. 3 Contents DECLARATION ......................................................................................... 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................. 3 ABSTRACT .............................................................................................. 9 PART ONE: ........................................................................................ -

Download Issue

YOUTH &POLICY No. 116 MAY 2017 Youth & Policy: The final issue? Towards a new format Editorial Group Paula Connaughton, Ruth Gilchrist, Tracey Hodgson, Tony Jeffs, Mark Smith, Jean Spence, Naomi Thompson, Tania de St Croix, Aniela Wenham, Tom Wylie. Associate Editors Priscilla Alderson, Institute of Education, London Sally Baker, The Open University Simon Bradford, Brunel University Judith Bessant, RMIT University, Australia Lesley Buckland, YMCA George Williams College Bob Coles, University of York John Holmes, Newman College, Birmingham Sue Mansfield, University of Dundee Gill Millar, South West Regional Youth Work Adviser Susan Morgan, University of Ulster Jon Ord, University College of St Mark and St John Jenny Pearce, University of Bedfordshire John Pitts, University of Bedfordshire Keith Popple, London South Bank University John Rose, Consultant Kalbir Shukra, Goldsmiths University Tony Taylor, IDYW Joyce Walker, University of Minnesota, USA Anna Whalen, Freelance Consultant Published by Youth & Policy, ‘Burnbrae’, Black Lane, Blaydon Burn, Blaydon on Tyne NE21 6DX. www.youthandpolicy.org Copyright: Youth & Policy The views expressed in the journal remain those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Editorial Group. Whilst every effort is made to check factual information, the Editorial Group is not responsible for errors in the material published in the journal. ii Youth & Policy No. 116 May 2017 About Youth & Policy Youth & Policy Journal was founded in 1982 to offer a critical space for the discussion of youth policy and youth work theory and practice. The editorial group have subsequently expanded activities to include the organisation of related conferences, research and book publication. Regular activities include the bi- annual ‘History of Community and Youth Work’ and the ‘Thinking Seriously’ conferences. -

Antisemitism

ANTISEMITISM ― OVERVIEW OF ANTISEMITIC INCIDENTS RECORDED IN THE EUROPEAN UNION 2009–2019 ANNUAL UPDATE ANNUAL © European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2020 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. For any use or reproduction of photos or other material that is not under the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights' copyright, permission must be sought directly from the copyright holders. Neither the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights nor any person acting on behalf of the Agency is responsible for the use that might be made of the following information. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2020 Print ISBN 978-92-9474-993-2 doi:10.2811/475402 TK-03-20-477-EN-C PDF ISBN 978-92-9474-992-5 doi:10.2811/110266 TK-03-20-477-EN-N Photo credits: Cover and Page 67: © Gérard Bottino (AdobeStock) Page 3: © boris_sh (AdobeStock) Page 12: © AndriiKoval (AdobeStock) Page 17: © Mikhail Markovskiy (AdobeStock) Page 24: © Jon Anders Wiken (AdobeStock) Page 42: © PackShot (AdobeStock) Page 50: © quasarphotos (AdobeStock) Page 58: © Igor (AdobeStock) Page 75: © Anze (AdobeStock) Page 80: © katrin100 (AdobeStock) Page 92: © Yehuda (AdobeStock) Contents INTRODUCTION � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 3 DATA COLLECTION ON ANTISEMITISM � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 4 LEGAL FRAMEWORK � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � -

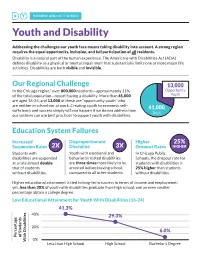

INFORM and ACT SERIES Youth and Disability

INFORM AND ACT SERIES Youth and Disability Addressing the challenges our youth face means taking disability into account. A strong region requires the equal opportunity, inclusion, and full participation of all residents. Disability is a natural part of the human experience. The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) defines disability as a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities. Disabilities are both visible and invisible. Our Regional Challenge 13,000 In the Chicago region,* over 800,000 residents—approximately 11% Opportunity of the total population—report having a disability. More than 41,000 Youth are aged 16-24, and 13,000 of these are “opportunity youth” who are neither in school nor at work. Creating a path to economic self- 41,000 sufficiency and success simply will not happen if we do not address how Total our systems can use best practices to support youth with disabilities. Education System Failures Increased Disproportionate Higher 25% Suspension Rates 2X Discipline 3X Dropout Rates HIGHER Students with Youth with emotional and In Chicago Public disabilities are suspended behavioral related disabilities Schools, the dropout rate for at a rate almost double are three times more likely to be students with disabilities is that of students arrested before leaving school, 25% higher than students without disabilities. compared to all other students. without disabilities. Higher educational attainment is tied to long-term success in terms of income and employment; yet, less than 30% of youth with disabilities graduate from high school, and an even smaller percentage obtain a college degree. Low Educational Attainment for Youth With Disabilities (16-24) 41.3% 40% 29.3% 20% 6.0% Percentage Percentage of Students 0% With Disabilities Less than High School High School Bachelor’s Degree Employment Gaps While mounting evidence demonstrates that hiring this overlooked talent pool can increase productivity and reduce costly turnover, barriers persist both when seeking employment and while on the job. -

Equal Protection for All Victims of Hate Crime the Case of People with Disabilities

03/2015 Equal protection for all victims of hate crime The case of people with disabilities Hate crimes violate the rights to human dignity and non-discrimination enshrined in the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union and the European Convention of Human Rights. Nevertheless, people with disabilities often face violence, discrimination and stigmatisation every day. This paper discusses the difficulties faced by people with disabilities who become victims of hate crime, and the different legal frameworks in place to protect such victims in the EU’s Member States. It ends by listing a number of suggestions for improving the situation at both the legislative and policy levels. Key facts FRA Opinions People with disabilities face discrimination, EU and national criminal law provisions stigmatisation and isolation every day, relating to hate crime should treat all which can be a formidable barrier to their grounds equally, from racism and inclusion and participation in the community xenophobia through to disability Disability is not included in the EU’s hate The EU and its Member States should crime legislation systematically collect and publish Victims of disability hate crime are often disaggregated data on hate crime, including reluctant to report their experiences hate crime against people with disabilities If incidents of disability hate crime are Law enforcement officers should be trained reported, the bias motivation is seldom and alert for indications of bias motivation recorded, making investigation and when investigating crimes prosecution less likely Trust-building measures should be undertaken to encourage reporting by disabled victims of bias-motivated or other forms of crime Equal protection for all victims of hate crime - The case of people with disabilities “[We want] to stop them being racist against us and stop some 80 million people in total. -

Interdisciplinary Disability Studies

YOUTH AND DISABILITY Interdisciplinary Disability Studies Series Editor: Mark Sherry, The University of Toledo, USA Disability studies has made great strides in exploring power and the body. This series extends the interdisciplinary dialogue between disability studies and other fields by asking how disability studies can influence a particular field. It will show how a deep engagement with disability studies changes our understanding of the following fields: sociology, literary studies, gender studies, bioethics, social work, law, education, and history. This ground-breaking series identifies both the practical and theoretical implications of such an interdisciplinary dialogue and challenges people in disability studies as well as other disciplinary fields to critically reflect on their professional praxis in terms of theory, practice, and methods. Other titles in the series Disability, Human Rights and the Limits of Humanitarianism Edited by Michael Gill and Cathy J. Schlund-Vials Disability and Social Movements Australian Perspectives Rachel Carling-Jenkins Forthcoming titles in the series Communication, Sport and Disability The Case of Power Soccer Michael S. Jeffress Disability and Qualitative Inquiry Methods for Rethinking an Ableist World Edited by Ronald J. Berger and Laura S. Lorenz Youth and Disability A Challenge to Mr Reasonable Jenny SlateR Sheffield Hallam University, UK First published 2015 by Ashgate Publishing Published 2016 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business Copyright © 2015 Jenny Slater Jenny Slater has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work. -

The Situation of Minority Children in Russia

The Situation of Children Belonging to Vulnerable Groups in Russia Alternative Report March 2013 Anti- Discrimination Centre “MEMORIAL” The NGO, Anti-Discrimination Centre “MEMORIAL”, was registered in 2007 and continued work on a number of human rights and anti-discrimination projects previously coordinated by the Charitable Educational Human Rights NGO “MEMORIAL” of St. Petersburg. ADC “Memorial‟s mission is to defend the rights of individuals subject to or at risk of discrimination by providing a proactive response to human rights violations, including legal assistance, human rights education, research, and publications. ADC Memorial‟s strategic goals are the total eradication of discrimination at state level; the adoption of anti- discrimination legislation in Russia; overcoming all forms of racism and nationalism; Human Rights education; and building tolerance among the Russian people. ADC Memorial‟s vision is the recognition of non-discrimination as a precondition for the realization of all the rights of each person. Tel: +7 (812) 317-89-30 E-mail: [email protected] Contributors The report has been prepared by Anti-discrimination Center “Memorial” with editorial direction of Stephania Kulaeva and Olga Abramenko. Anti-discrimination Center “Memorial” would like to thank Simon Papuashvili of International Partnership for Human Rights for his assistance in putting this report together and Ksenia Orlova of ADC “Memorial” for allowing us to use the picture for the cover page. Page 2 of 47 Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ 4 Summary of Recommendations ..................................................................................................... 7 Overview of the legal and policy initiatives implemented in the reporting period ................. 11 Violations of the rights of children involving law enforcement agencies ............................... -

The Policy of Multicultural Education in Russia: Focus on Personal Priorities

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ENVIRONMENTAL & SCIENCE EDUCATION 2016, VOL. 11, NO. 18, 12613-12628 OPEN ACCESS THE POLICY OF MULTICULTURAL EDUCATION IN RUSSIA: FOCUS ON PERSONAL PRIORITIES a a Natalya Yuryevna Sinyagina , Tatiana Yuryevna Rayfschnayder , a Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration, RUSSIA, ABSTRACT The article contains the results of the study of the current state of multicultural education in Russia. The history of studying the problem of multicultural education has been analyzed; an overview of scientific concepts and research of Russian scientists in the sphere of international relations, including those conducted under defended theses, and the description of technologies of multicultural education in Russia (review of experience, programs, curricula and their effectiveness) have been provided. The ways of the development of multicultural education in Russia have been described. Formulation of the problem of the development of multicultural education in the Russian Federation is currently associated with a progressive trend of the inter- ethnic and social differentiation, intolerance and intransigence, which are manifested both in individual behavior (adherence to prejudices, avoiding contacts with the "others", proneness to conflict) and in group actions (interpersonal aggression, discrimination on any grounds, ethnic conflicts, etc.). A negative attitude towards people with certain diseases, disabilities, HIV-infected people, etc., is another problem at the moment. This situation also -

Anglo-Jewry's Experience of Secondary Education

Anglo-Jewry’s Experience of Secondary Education from the 1830s until 1920 Emma Tanya Harris A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements For award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Hebrew and Jewish Studies University College London London 2007 1 UMI Number: U592088 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U592088 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract of Thesis This thesis examines the birth of secondary education for Jews in England, focusing on the middle classes as defined in the text. This study explores various types of secondary education that are categorised under one of two generic terms - Jewish secondary education or secondary education for Jews. The former describes institutions, offered by individual Jews, which provided a blend of religious and/or secular education. The latter focuses on non-Jewish schools which accepted Jews (and some which did not but were, nevertheless, attended by Jews). Whilst this work emphasises London and its environs, other areas of Jewish residence, both major and minor, are also investigated. -

Directory of Organisations and Resources for People with Disabilities in South Africa

DISABILITY ALL SORTS A DIRECTORY OF ORGANISATIONS AND RESOURCES FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES IN SOUTH AFRICA University of South Africa CONTENTS FOREWORD ADVOCACY — ALL DISABILITIES ADVOCACY — DISABILITY-SPECIFIC ACCOMMODATION (SUGGESTIONS FOR WORK AND EDUCATION) AIRLINES THAT ACCOMMODATE WHEELCHAIRS ARTS ASSISTANCE AND THERAPY DOGS ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR HIRE ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR PURCHASE ASSISTIVE DEVICES — MAIL ORDER ASSISTIVE DEVICES — REPAIRS ASSISTIVE DEVICES — RESOURCE AND INFORMATION CENTRE BACK SUPPORT BOOKS, DISABILITY GUIDES AND INFORMATION RESOURCES BRAILLE AND AUDIO PRODUCTION BREATHING SUPPORT BUILDING OF RAMPS BURSARIES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — EASTERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — FREE STATE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — GAUTENG CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — KWAZULU-NATAL CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — LIMPOPO CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — MPUMALANGA CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTHERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTH WEST CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — WESTERN CAPE CHARITY/GIFT SHOPS COMMUNITY SERVICE ORGANISATIONS COMPENSATION FOR WORKPLACE INJURIES COMPLEMENTARY THERAPIES CONVERSION OF VEHICLES COUNSELLING CRÈCHES DAY CARE CENTRES — EASTERN CAPE DAY CARE CENTRES — FREE STATE 1 DAY CARE CENTRES — GAUTENG DAY CARE CENTRES — KWAZULU-NATAL DAY CARE CENTRES — LIMPOPO DAY CARE CENTRES — MPUMALANGA DAY CARE CENTRES — WESTERN CAPE DISABILITY EQUITY CONSULTANTS DISABILITY MAGAZINES AND NEWSLETTERS DISABILITY MANAGEMENT DISABILITY SENSITISATION PROJECTS DISABILITY STUDIES DRIVING SCHOOLS E-LEARNING END-OF-LIFE DETERMINATION ENTREPRENEURIAL