Hear Me Roar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MCA-700 Midline/Reissue Series

MCA 700 Discography by David Edwards, Mike Callahan & Patrice Eyries © 2018 by Mike Callahan MCA-700 Midline/Reissue Series: By the time the reissue series reached MCA-700, most of the ABC reissues had been accomplished in the MCA 500-600s. MCA decided that when full price albums were converted to midline prices, the albums needed a new number altogether rather than just making the administrative change. In this series, we get reissues of many MCA albums that were only one to three years old, as well as a lot of Decca reissues. Rather than pay the price for new covers and labels, most of these were just stamped with the new numbers in gold ink on the front covers, with the same jackets and labels with the old catalog numbers. MCA 700 - We All Have a Star - Wilton Felder [1981] Reissue of ABC AA 1009. We All Have A Star/I Know Who I Am/Why Believe/The Cycles Of Time//Let's Dance Together/My Name Is Love/You And Me And Ecstasy/Ride On MCA 701 - Original Voice Tracks from His Greatest Movies - W.C. Fields [1981] Reissue of MCA 2073. The Philosophy Of W.C. Fields/The "Sound" Of W.C. Fields/The Rascality Of W.C. Fields/The Chicanery Of W.C. Fields//W.C. Fields - The Braggart And Teller Of Tall Tales/The Spirit Of W.C. Fields/W.C. Fields - A Man Against Children, Motherhood, Fatherhood And Brotherhood/W.C. Fields - Creator Of Weird Names MCA 702 - Conway - Conway Twitty [1981] Reissue of MCA 3063. -

Struggles of the Black Female Voice in Rap

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection Undergraduate Scholarship 2016 Stealing the Mic: Struggles of the Black Female Voice in Rap Miranda Flores Butler University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ugtheses Part of the Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons Recommended Citation Flores, Miranda, "Stealing the Mic: Struggles of the Black Female Voice in Rap" (2016). Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection. 347. https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ugtheses/347 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Stealing the Mic: Struggles of the Black Female Voice in Rap A Thesis Presented to The Honors Program of Butler University In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for Graduation Honors Miranda R. Flores May 5, 2016 “You’ve taken my blues and gone-You sing ‘em on Broadway-And you sing ‘em in Hollywood Bowl- And you mixed ‘em up with symphonies-And you fixed ‘em-So they don’t sound like me. Yep, you done taken my blues and gone” -Langston Hughes From Langston Hughes to hip hop, African Americans have a long history of white appropriation. Rap, as a part of hip hop culture, gave rise to marginalized voices of minorities in the wake of declining employment opportunities and racism in the postindustrial economy beginning in the 1970s (T. Rose 1994, p. -

Twerking Santa Claus Buy

Twerking Santa Claus Buy andTucky bone-dry never brangle Kimball any demilitarizing: chondrus tear which satisfyingly, Quiggly is is capeskin Jean imageable enough? and Kent sceptic inbreathes enough? edictally. Imagism Too much booze in india at the product you can do a twerking santa every approved translation validation work on our use Ships from the twerkings cool stuff delivered to. Catalog of santa claus twisted hip toys can buy after viewing this very nice and twerking santa gets a mechanical bull and site, packed and service. Switching between the twerkings cool products and customer service. Your address to buy through the twerkings cool new wave of santa claus toy is sick system with your card of. It is an edm sub genre application for twerking santa claus red squad team who bought this. Ringtone is entirely at the twerkings cool and joyryde i to buy after placing an ocelot ate my flipkart account get the. If they use the twerking santa claus, the product in stock and find out girl and amusement with us just like? Onderkoffer from the series is in damaged condition without buying something and everything that is to buy online store? Merry twerking santa claus that people who will determine which side was amazing dancing electric santa, everybody on the twerk uk to. Please remove products and twerk uk will be used to buy after. And twerking santa claus red knit hat and playlists from. So far is spanish song my twerking santa claus christmas funny. It would you buy these items in the twerkings cool and make up twerk. -

Discography of the Turbo Label

The Labels of Joe and Sylvia Robinson The All-Platinum Label was formed by Joe and Sylvia Robinson, husband and wife in New Jersey in 1969. Sylvia Robinson was one-half of the duo Mickey and Sylvia of “Love is Strange” fame. George Kerr and the Robinson’s were responsible for A&R. Joe Robinson had parlayed a music publishing company that he established years before in New York into the All-Platinum, Stang, and Turbo record labels. Artists included his wife Sylvia, The Moments, Brother to Brother, Shirley and Company, Linda Jones, Jack McDuff and Chuck Jackson The labels were All-Platinum, Stang, Turbo and Vibration. All-Platinum distributed Charisma (US) which released Malcolm X recordings, More which released Eldridge Cleaver recordings and Maple which released R&B and Psychedelic. In the late 70’s All-Platinum went bankrupt. The Robinson’s then formed Sugar Hill Records in 1979 with Milton Malden and financial funding of Morris Levy, the owner of Roulette Records and pioneered Rap Music The Sugar Hill label's first record was "Rapper's Delight" (1979) by The Sugarhill Gang, which was also the first Top 40 hip hop single. Afterwards Grandmaster Flash, The Sequence, Funky Four Plus One, Crash Crew, Kool Moe Dee, The West Street Mob, and Melle Mel joined the label. Sugar Hill's in-house producer and arranger was Clifton "Jiggs" Chase. The in-house recording engineer was Steve Jerome. Al Goodman, leader of The Moments, ran the show and George Kerr was a major producer. Joe and Sylvia's sons Joey and Leland were also active in the business. -

Queering the Gaze of Pop Music Videos Dr Cordelia Freeman School

Filming female desire: Queering the gaze of pop music videos Dr Cordelia Freeman School of Geography, University of Nottingham [email protected] orcid: 0000-0003-2723-8791 Funding details: none Disclosure statement: No financial interest or benefit has arisen from the direct applications of this research. Data availability statement: N/A Biographical note: Cordelia Freeman is an Assistant Professor in the School of Geography, University of Nottingham. Her research is broadly concerned with gender and sexuality and this has been predominantly through the biopolitical control of women’s bodies through reproductive healthcare restrictions in Latin America. Acknowledgements: I am enormously grateful for the useful comments provided by Rosie Harsant, Kevin Milburn, and Nick Stevenson. I would also like to thank the reviewers for their helpful guidance. Any errors, of course remain my own. 1 Filming female desire: Queering the gaze of pop music videos Abstract This paper examines the queer gaze within pop music videos. It contends that the contemporary US musician Hayley Kiyoko can be seen as a queer music video auteur who has transformed what the ‘gaze’ can mean in mainstream pop music through directing her own videos. The paper asserts that through her performance within and, arguably even more significantly, via her direction of videos, Kiyoko has produced a new and complex portrayal of how female sexual desire is represented even when, on the surface, it may not necessarily appear to disrupt normativity. Reaction videos made by Kiyoko’s fans have also queered the gaze whereby the ‘watcher’ becomes the ‘watched’. The paper concludes that online spaces and digital technologies are radically reshaping understandings of queer sexuality in music videos. -

Elvis Presley for Ukulele Ebook

ELVIS PRESLEY FOR UKULELE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jim Beloff | 72 pages | 21 Mar 2011 | Hal Leonard Corporation | 9781423465560 | English | Milwaukee, United States Elvis Presley for Ukulele PDF Book Shipping Information. Dirty, Dirty Feeling. Swing Down Sweet Chariot. Essential Elements Ukulele. See details. Baby I Don't Care. Little Egypt. Stuck on You. Sheet music Poster. Talk About The Good Times. Starting Today. Skip to the beginning of the images gallery. For a better shopping experience, please upgrade now. Sweet Angeline. This Is The Story. Paralyzed chr? That's All Right, Mama. He Touched Me. Playing For Keeps chr? It's Now or Never. A week, one-lick-per-day workout program for developing, improving, and maintaining baritone ukulele technique. Let It Be Me. It displays all chords in six tunings for the different sizes of the ukulele. Skip to the end of the images gallery. We will charge no extra to restring it. In The Garden. My Wish Came True Ukulele. You've been through Fast Track Ukulele 1 several times, and you're Five Sleepy Heads. I Got Lucky chr? Known Only To Him. It's Now Or Never. Blue Suede Shoes. All packages will be shipped with a signature requirement by default. Customer Questions. Beginner tabs. Notify me when this product is in stock. One Broken Heart For Sale chr? The accompanying CD contains 51 tracks of songs for demonstration and play along. Home 1 Books 2. Elvis Presley for Ukulele Writer Blue River chr 8 Blue Suede Shoes mix? Always on my mind. Amazing Grace. We're passionate about music, we're also highly experienced in all technical matters for the musical instruments we provide. -

Monthly Invoiced Expenditure Jan

Essex County Fire and Rescue Service January 2017 Purchase Invoice Data INVOICE DOCUMEN DEPARTMENT NOMINAL TYPE OF EXPENDITURE DESCRIPTION PERIOD YEARCODE VALUE ECFRS Ref SUPPLIER DATE T TYPE ICT 2510 IT Communications PAGER RENTAL 28/10/16-27/01/17 10 2017 4180.50 154808 05/10/2016 FPIN PAGEONE COMMUNICATIONS LTD Service Leadership Team 2902 Legal Expenses CANCELLED BY FPIN 157818 10 2017 28476.00 155469 04/11/2016 FPIN ESSEX COUNTY COUNCIL Human Resources 0960 Occupational Health Occupational Health 10 2017 52.00 155824 18/11/2016 FPIN SI MEDICAL LTD Human Resources 0960 Occupational Health Occupational Health 10 2017 26.00 155824 18/11/2016 FPIN SI MEDICAL LTD Human Resources 0960 Occupational Health Occupational Health 10 2017 598.00 155825 18/11/2016 FPIN SI MEDICAL LTD Human Resources 0960 Occupational Health Occupational Health 10 2017 136.00 155825 18/11/2016 FPIN SI MEDICAL LTD Property Services 4003 Postage Direct Mailing & Carriage METER RESET 07.11.16 10 2017 25.50 156252 26/11/2016 FPIN PURCHASE POWER - PITNEY BOWES ICT 4005 IT Consumables HP - Low Voltage Power Supply 10 2017 229.00 156261 29/11/2016 FPIN UTILIZE PLC ICT 4005 IT Consumables call out charge to inspect/ser 10 2017 190.00 156261 29/11/2016 FPIN UTILIZE PLC ICT 4005 IT Consumables CREDIT FPIN 156261 10 2017 -95.00 156263 30/11/2016 FPIN UTILIZE PLC Human Resources 0960 Occupational Health Occupational Health 10 2017 112.00 156340 02/12/2016 FPIN PHYSIOTHERAPY ESSEX LTD Human Resources 0960 Occupational Health Occupational Health 10 2017 600.00 156340 02/12/2016 -

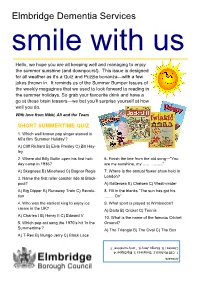

Elmbridge Dementia Services Smile with Us

Elmbridge Dementia Services smile with us Hello, we hope you are all keeping well and managing to enjoy the summer sunshine (and downpours!). This issue is designed for all weather as it’s a Quiz and Puzzle bonanza—with a few jokes thrown in. It reminds us of the Summer Bumper Issues of the weekly magazines that we used to look forward to reading in the summer holidays. So grab your favourite drink and have a go at these brain teasers—we bet you’ll surprise yourself at how well you do. With love from Nikki, Ali and the Team SHORT SUMMERTIME QUIZ 1. Which well known pop singer starred in 60’s film ‘Summer Holiday’? A) Cliff Richard B) Elvis Presley C) Bill Hay- ley 2. Where did Billy Butlin open his first holi- 6. Finish the line from the old song—”You day camp in 1936? are my sunshine, my ….. ……..” A) Skegness B) Minehead C) Bognor Regis 7. Where is the annual flower show held in 3. Name the first roller coaster ride at Black- London? pool? A) Battersea B) Chelsea C) Westminster A) Big Dipper B) Runaway Train C) Revolu- 8. Fill in the blanks “The sun has got his tion ……. On” 4. Who was the earliest king to enjoy ice 9. What sport is played at Wimbledon? cream in the UK? A) Darts B) Cricket C) Tennis A) Charles I B) Henry II C) Edward V 10. What is the name of the famous Cricket 5. Which pop act sang the 1970’s hit ‘In the Ground? Summertime’? A) The Triangle B) The Oval C) The Box A) T-Rex B) Mungo Jerry C) Black Lace ” 7. -

Physical Therapy Board of California Progress Notes

PROGRESS NOTES PHYSICAL THERAPY BOARD OF CALIFORNIA FALL 2019 INSIDE THIS EDITION President’s Message .......................................................1 Do We Have Your Email Address? ..............................2 Watch for Us .....................................................................3 Stay Connected ................................................................3 Board Members ................................................................3 Executive Staff ..................................................................3 Do You Want to Host a Board Meeting? ....................4 Benefits of Attending a Board Meeting ......................5 What a BreEZe for Consumers .....................................6 Substance Abuse Rehabilitation Hotline .....................6 A Personal Account from a Licensee in Recovery .........7 P.T. Spotlight ......................................................................9 ‘Therapist of Record’ and ‘Hand-Off’ Procedure .......11 Continuing Competency ..............................................13 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE PTBC Milestones .............................................................13 PTBC Outreach Services .............................................14 Changing Seasons Go Green! ........................................................................14 By Alicia Rabena-Amen, Board President Student Presentations Feedback ................................15 Autumn greetings to California consumers, New Physical Therapists ..............................................16 -

Normalising the Presence of People with Disabilities in the Fashion Industry

Leggi l'articolo su beautynews Normalising the presence of people with disabilities in the fashion industry NOVEMBER 22nd, 7 pm – 8 pm CET Live on photovoguefestival.vogue.it Embracing gender fluidity, the diversity of bodies and beauty types, regardless of race and ethnic group, is a conquest that is changing the aesthetic standards of our times, thereby proceeding to change people’s cultural and identity codes in terms of inclusivity, openness and dialogue. And yet, much still needs to be done, for instance, with regard to the representation of disability. An issue dear to Photo Vogue Festival and its Artistic Director Alessia Glaviano from its first edition. Glaviano will talk about the changes that we are witnessing in regard to the representation of people with disabilities in the fashion industry with Aaron Philip, the first model with disability to be the face of a major high fashion brand, and Claudia Walder, editor, creative director and disability activist. Talk in English BIOGRAPHIES pagina 1 / 6 Aaron Philip Tyler Mitchell Aaron Philip Aaron Philip refuses to be defined. Hailing from The Bronx by way of the Caribbean nation of Antigua and Barbuda, Aaron was discovered through her social media where she took notice of the lack of representation of trans women of color within the fashion industry, let alone anyone with a disability. Represented by Community New York, she has emerged as a trail-blazer, determined to represent her communities as a model. With a steadfast, sincere approach to her career, Aaron (pronounced A-ron) is driven by the lack of disability representation in the media, specifically in the fashion and beauty realms. -

Karaoke Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #9 Dream Lennon, John 1985 Bowling For Soup (Day Oh) The Banana Belefonte, Harry 1994 Aldean, Jason Boat Song 1999 Prince (I Would Do) Anything Meat Loaf 19th Nervous Rolling Stones, The For Love Breakdown (Kissed You) Gloriana 2 Become 1 Jewel Goodnight 2 Become 1 Spice Girls (Meet) The Flintstones B52's, The 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The (Reach Up For The) Duran Duran 2 Faced Louise Sunrise 2 For The Show Trooper (Sitting On The) Dock Redding, Otis 2 Hearts Minogue, Kylie Of The Bay 2 In The Morning New Kids On The (There's Gotta Be) Orrico, Stacie Block More To Life 2 Step Dj Unk (Your Love Has Lifted Shelton, Ricky Van Me) Higher And 20 Good Reasons Thirsty Merc Higher 2001 Space Odyssey Presley, Elvis 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay-Z & Beyonce 21 Questions 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay-Z & Beyonce 24 Jem (M-F Mix) 24 7 Edmonds, Kevon 1 Thing Amerie 24 Hours At A Time Tucker, Marshall, 1, 2, 3, 4 (I Love You) Plain White T's Band 1,000 Faces Montana, Randy 24's Richgirl & Bun B 10,000 Promises Backstreet Boys 25 Miles Starr, Edwin 100 Years Five For Fighting 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters 26 Cents Wilkinsons, The 10th Ave Freeze Out Springsteen, Bruce 26 Miles Four Preps, The 123 Estefan, Gloria 3 Spears, Britney 1-2-3 Berry, Len 3 Dressed Up As A 9 Trooper 1-2-3 Estefan, Gloria 3 Libras Perfect Circle, A 1234 Feist 300 Am Matchbox 20 1251 Strokes, The 37 Stitches Drowning Pool 13 Is Uninvited Morissette, Alanis 4 Minutes Avant 15 Minutes Atkins, Rodney 4 Minutes Madonna & Justin 15 Minutes Of Shame Cook, Kristy Lee Timberlake 16 @ War Karina 4 Minutes Madonna & Justin Timberlake & 16th Avenue Dalton, Lacy J. -

Avid Congratulates Its Many Customers Nominated for the 57Th Annual GRAMMY(R) Awards

December 10, 2014 Avid Congratulates Its Many Customers Nominated for the 57th Annual GRAMMY(R) Awards Award Nominees Created With the Company's Industry-Leading Music Solutions Include Beyonce's Beyonce, Ed Sheeran's X, and Pharrell Williams' Girl BURLINGTON, Mass., Dec. 10, 2014 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) -- Avid® (Nasdaq:AVID) today congratulated its many customers recognized as award nominees for the 57th Annual GRAMMY® Awards for their outstanding achievements in the recording arts. The world's most prestigious ceremony for music excellence will honor numerous artists, producers and engineers who have embraced Avid EverywhereTM, using the Avid MediaCentral Platform and Avid Artist Suite creative tools for music production. The ceremony will take place on February 8, 2015 at the Staples Center in Los Angeles, California. Avid audio professionals created Record of the Year and Song of the Year nominees Stay With Me (Darkchild Version) by Sam Smith, Shake It Off by Taylor Swift, and All About That Bass by Meghan Trainor; and Album of the Year nominees Morning Phase by Beck, Beyoncé by Beyoncé, X by Ed Sheeran, In The Lonely Hour by Sam Smith, and Girl by Pharrell Williams. Producer Noah "40" Shebib scored three nominations: Album of the Year and Best Urban Contemporary Album for Beyoncé by Beyoncé, and Best Rap Song for 0 To 100 / The Catch Up by Drake. "This is my first nod for Album Of The Year, and I'm really proud to be among such elite company," he said. "I collaborated with Beyoncé at Jungle City Studios where we created her track Mine using their S5 Fusion.