Centralization, Decentralization and Conflict in the Middle East and North Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Muzaffargarh

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! Overview - Muzaffargarh ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Bhattiwala Kherawala !Molewala Siwagwala ! Mari PuadhiMari Poadhi LelahLeiah ! ! Chanawala ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Ladhranwala Kherawala! ! ! ! Lerah Tindawala Ahmad Chirawala Bhukwala Jhang Tehsil ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Lalwala ! Pehar MorjhangiMarjhangi Anwarwal!a Khairewala ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Wali Dadwala MuhammadwalaJindawala Faqirewala ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! MalkaniRetra !Shah Alamwala ! Bhindwalwala ! ! ! ! ! Patti Khar ! ! ! Dargaiwala Shah Alamwala ! ! ! ! ! ! Sultanwala ! ! Zubairwa(24e6)la Vasawa Khiarewala ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Jhok Bodo Mochiwala PakkaMochiwala KumharKumbar ! ! ! ! ! ! Qaziwala ! Haji MuhammadKhanwala Basti Dagi ! ! ! ! ! Lalwala Vasawa ! ! ! Mirani ! ! Munnawala! ! ! Mughlanwala ! Le! gend ! Sohnawala ! ! ! ! ! Pir Shahwala! ! ! Langanwala ! ! ! ! Chaubara ! Rajawala B!asti Saqi ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! BuranawalaBuranawala !Gullanwala ! ! ! ! ! Jahaniawala ! ! ! ! ! Pathanwala Rajawala Maqaliwala Sanpalwala Massu Khanwala ! ! ! ! ! ! Bhandniwal!a Josawala ! ! Basti NasirBabhan Jaman Shah !Tarkhanwala ! !Mohanawala ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Basti Naseer Tarkhanwala Mohanawala !Citiy / Town ! Sohbawala ! Basti Bhedanwala ! ! ! ! ! ! Sohaganwala Bhurliwala ! ! ! ! Thattha BulaniBolani Ladhana Kunnal Thal Pharlawala ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Ganjiwala Pinglarwala Sanpal Siddiq Bajwa ! ! ! ! ! Anhiwala Balochanwala ! Pahrewali ! ! Ahmadwala ! ! ! -

Pathologies of Centralized State-Building by Jennifer Murtazashvili

In 2011, Afghan government and International Security Assistance Force officials take part in a shura with elders in Zabul province, Afghanistan. The Zabul Provincial Reconstruction Team visited the village to talk with elders and help Afghan National Security Forces distribute winter supplies. (U.S. Air Force/Brian Ferguson) 54 | FEATURES PRISM 8, NO. 2 Pathologies of Centralized State-Building By Jennifer Murtazashvili he international community, led by the United States, has invested trillions of dollars in state-build- ing efforts during the past two decades. Yet despite this commitment of substantial resources, conflict and violence remain a challenge in fragile states. It therefore seems especially important to Tconsider the reasons why state-building has not lived up to its expectations. Past state-building efforts were predicated on the belief that a centralized government would improve prospects for political order and economic development. These efforts therefore have typically empha- sized powerful national governments and centralized bureaucratic administration as the keys to generating improvements in the state’s provision of public goods, including rule of law and collective security. This article challenges the underlying assumptions to that approach, arguing that centralization actu- ally undermines efforts to stabilize and rebuild fragile states. It describes several risks centralization poses for effective state-building. For example, many highly centralized governments prey on their own citizens and are therefore prone to civil unrest, conflict, and collapse.1 Most of the countries that have experienced pro- longed civil conflict over the past several decades—including Afghanistan, Libya, Myanmar, Somalia, Syria, and Yemen—had extremely centralized governments prior to the outbreak of conflict. -

The Informal Sector and Economic Growth of South Africa and Nigeria: a Comparative Systematic Review

Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity Review The Informal Sector and Economic Growth of South Africa and Nigeria: A Comparative Systematic Review Ernest Etim and Olawande Daramola * Department of Information Technology, Cape Peninsula University of Technology, P.O. Box 652, South Africa; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 17 August 2020; Accepted: 10 October 2020; Published: 6 November 2020 Abstract: The informal sector is an integral part of several sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries and plays a key role in the economic growth of these countries. This article used a comparative systematic review to explore the factors that act as drivers to informality in South Africa (SA) and Nigeria, the challenges that impede the growth dynamics of the informal sector, the dominant subsectors, and policy initiatives targeting informal sector providers. A systematic search of Google Scholar, Scopus, ResearchGate was performed together with secondary data collated from grey literature. Using Boolean string search protocols facilitated the elucidation of research questions (RQs) raised in this study. An inclusion and exclusion criteria became necessary for rigour, comprehensiveness and limitation of publication bias. The data collated from thirty-one (31) primary studies (17 for SA and 14 for Nigeria) revealed that unemployment, income disparity among citizens, excessive tax burdens, excessive bureaucratic hurdles from government, inflationary tendencies, poor corruption control, GDP per capita, and lack of social protection survival tendencies all act as drivers to the informal sector in SA and Nigeria. Several challenges are given for both economies and policy incentives that might help sustain and improve the informal sector in these two countries. -

Austria FULL Constitution

AUSTRIA THE FEDERAL CONSTITUTIONAL LAW OF 1920 as amended in 1929 as to Law No. 153/2004, December 30, 2004 Table of Contents CHAPTER I General Provisions European Union CHAPTER II Legislation of the Federation CHAPTER III Federal Execution CHAPTER IV Legislation and Execution by the Länder CHAPTER V Control of Accounts and Financial Management CHAPTER VI Constitutional and Administrative Guarantees CHAPTER VII The Office of the People’s Attorney ( Volksanwaltschaft ) CHAPTER VIII Final Provisions CHAPTER I General Provisions European Union A. General Provisions Article 1 Austria is a democratic republic. Its law emanates from the people. Article 2 (1) Austria is a Federal State. (2) The Federal State is constituted from independent Länder : Burgenland, Carinthia, Lower Austria, Upper Austria, Salzburg, Styria, Tirol, Vorarlberg and Vienna. Article 3 (1) The Federal territory comprises the territories ( Gebiete ) of the Federal Länder . (2) A change of the Federal territory, which is at the same time a change of a Land territory (Landesgebiet ), just as the change of a Land boundary inside the Federal territory, can—apart from peace treaties—take place only from harmonizing constitutional laws of the Federation (Bund ) and the Land , whose territory experiences change. Article 4 (1) The Federal territory forms a unitary currency, economic and customs area. (2) Internal customs borders ( Zwischenzollinien ) or other traffic restrictions may not be established within the Federation. Article 5 (1) The Federal Capital and the seat of the supreme bodies of the Federation is Vienna. (2) For the duration of extraordinary circumstances the Federal President, on the petition of the Federal Government, may move the seat of the supreme bodies of the Federation to another location in the Federal territory. -

Austrian Federalism in Comparative Perspective

CONTEMPORARY AUSTRIAN STUDIES | VOLUME 24 Bischof, Karlhofer (Eds.), Williamson (Guest Ed.) • 1914: Aus tria-Hungary, the Origins, and the First Year of World War I War of World the Origins, and First Year tria-Hungary, Austrian Federalism in Comparative Perspective Günter Bischof AustrianFerdinand Federalism Karlhofer (Eds.) in Comparative Perspective Günter Bischof, Ferdinand Karlhofer (Eds.) UNO UNO PRESS innsbruck university press UNO PRESS innsbruck university press Austrian Federalism in ŽŵƉĂƌĂƟǀĞWĞƌƐƉĞĐƟǀĞ Günter Bischof, Ferdinand Karlhofer (Eds.) CONTEMPORARY AUSTRIAN STUDIES | VOLUME 24 UNO PRESS innsbruck university press Copyright © 2015 by University of New Orleans Press All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage nd retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. All inquiries should be addressed to UNO Press, University of New Orleans, LA 138, 2000 Lakeshore Drive. New Orleans, LA, 70148, USA. www.unopress.org. Printed in the United States of America Book design by Allison Reu and Alex Dimeff Cover photo © Parlamentsdirektion Published in the United States by Published and distributed in Europe University of New Orleans Press by Innsbruck University Press ISBN: 9781608011124 ISBN: 9783902936691 UNO PRESS Publication of this volume has been made possible through generous grants from the the Federal Ministry for Europe, Integration, and Foreign Affairs in Vienna through the Austrian Cultural Forum in New York, as well as the Federal Ministry of Economics, Science, and Research through the Austrian Academic Exchange Service (ÖAAD). The Austrian Marshall Plan Anniversary Foundation in Vienna has been very generous in supporting Center Austria: The Austrian Marshall Plan Center for European Studies at the University of New Orleans and its publications series. -

Austria Österreich

eGovernment Factsheets January 2007 [ eGovernment in ] Version 7.0 Austria Österreich Country Profile History eGovernment Strategy eGovernment Legal Framework Actors eGovernment Who’s Who eGovernment Infrastructure Services for Citizens eGovernment Services for Businesses What’s Inside European Commission http://ec.europa.eu/idabc/egovo [ eGovernment Factsheets - Austria ] Contents: Country Profile..........................................................................Profile.........................................................................1 eGovernment History.................................................................History................................................................3 eGovernment Strategy.............................................................Strategy.............................................................109 eGovernment Legal Framework...............................................1412 eGovernment Actors................................................................Actors...............................................................1516 eGovernment Who’s Who........................................................2018 eGovernment Infrastructure.....................................................2124 eGovernment Services for Citizens...........................................2824 eGovernment Services for Businesses.......................................3530 Disclaimer: This document is not intended to be exhaustive. Its purpose is to give an overview of the general e-government situation -

Contextualising Austria's Commemorative Year 2005 Matthew .P Berg John Carroll University, [email protected]

John Carroll University Carroll Collected History 1-2008 Commemoration versus coping with the past: contextualising Austria's commemorative year 2005 Matthew .P Berg John Carroll University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://collected.jcu.edu/hist-facpub Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Berg, Matthew P., "Commemoration versus coping with the past: contextualising Austria's commemorative year 2005" (2008). History. 19. http://collected.jcu.edu/hist-facpub/19 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Carroll Collected. It has been accepted for inclusion in History by an authorized administrator of Carroll Collected. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Commemoration versus Vergangenheitsbewältigung: Contextualizing Austria’s Gedenkjahr 2005* Abstract This essay explores the politics of memory in post-1945 Austrian political culture, focusing on the shift between the fiftieth anniversary of the Anschluss and the sixtieth anniversary of the end of the Second World War. Postwar Austrian society experienced a particular tension associated with the Nazi past, manifested in communicative and cultural forms of memory. On the one hand, the support of many for the Third Reich—expressed through active or passive complicity—threatened to link Austria with the perpetrator status reserved for German society. On the other, the Allies’ Moscow Declaration (1943) created a myth of victimization by Germany that allowed Austrians to avoid confronting difficult questions concerning the Nazi era. Consequently, discussion of Austrian involvement in National Socialism became a taboo subject during the initial decades of the Second Republic. The 2005 commemoration is notable insofar as it marked a significant break with this taboo. -

How Government Structure Encourages Criminal Violence: the Causes of Mexico's Drug War

How Government Structure Encourages Criminal Violence: The causes of Mexico's Drug War The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Rios Contreras, Viridiana. 2013. How Government Structure Encourages Criminal Violence: The causes of Mexico's Drug War. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:11156675 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA c 2012—Viridiana Rios All rights reserved. ProfessorJorgeI.Dom´ınguez ViridianaRiosContreras How Government Structure Encourages Criminal Violence: The Causes of Mexico’s Drug War Abstract This work advances a theory about corruption, criminal organizations, and violence to show how political institutions set incentives and constraints that lead criminal organi- zations behave, organize, compromise or fight one another. It is my argument that the propensity of criminal groups to deploy violence increases when formal or informal polit- ical institutions are decentralized because violent criminal organizations are less likely to be punished. Under decentralized institutional environments, understood here as those in which different levels of government fail to act cohesively as a single decision-making body, corruption agreements with one government inhibit law enforcement operations conducted by another. As a result, belligerent criminal organizations that would other- wise be punished remain untouched. My argument sheds light on why many criminal organizations are able to operate profitably without major episodes of violence, and illu- minates the causes of Mexico’s large increases in drug–related violence. -

Decentralized Forms of Government

A Practical Guide to Constitution Building: Decentralized Forms of Government Markus Böckenförde This paper appears as chapter 7 of International IDEA’s publication A Practical Guide to Constitution Building. The full Guide is available in PDF and as an e-book at <http://www.idea.int> and includes an introductory chapter (chapter 1) and chapters on principles and cross-cutting themes in constitution building (chapter 2), building a culture of human rights (chapter 3), and constitution building and the design of the executive branch, the legislature and the judiciary (chapters 4, 5 and 6). International IDEA resources on Constitution Building A Practical Guide to Constitution Building: Decentralized Forms of Government © International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International IDEA), 2011 This publication is independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA, its Board or its Council of Member States, or those of the donors. Applications for permission to reproduce all or any part of this publication should be made to: International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International IDEA) Strömsborg SE -103 34 Stockholm Sweden Tel: +46-8-698 37 00 Fax: +46-8-20 24 22 Email: [email protected] Website: www.idea.int Design and layout by: Turbo Design, Ramallah Printed by: Bulls Graphics, Sweden Cover design by: Turbo Design, Ramallah Cover illustration by: Sharif Sarhan ISBN: 978-91-86565-34-3 This publication is produced as part of the Constitution Building Programme implemented by International IDEA with funding from the Royal Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. -

Human Rights Reports in Europe

HUMAN RIGHTS IN EUROPE REVIEW OF 2019 Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2020 Cover photo: Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed A protester speaks through a megaphone as under a Creative Commons (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, smoke from coloured smoke bombs billows near international 4.0) licence. people taking part in the annual May Day rally in https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Strasbourg, eastern France, on May 1, 2019. For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: © PATRICK HERTZOG/AFP via Getty Images www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2020 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street, London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: EUR 01/2098/2020 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS REGIONAL OVERVIEW 4 ALBANIA 8 AUSTRIA 10 BELGIUM 12 BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 14 BULGARIA 16 CROATIA 18 CYPRUS 20 CZECH REPUBLIC 22 DENMARK 24 ESTONIA 26 FINLAND 27 FRANCE 29 GERMANY 32 GREECE 35 HUNGARY 38 IRELAND 41 ITALY 43 LATVIA 46 LITHUANIA 48 MALTA 49 MONTENEGRO 51 THE NETHERLANDS 53 NORTH MACEDONIA 55 NORWAY 57 POLAND 59 PORTUGAL 62 ROMANIA 64 SERBIA 66 SLOVAKIA 69 SLOVENIA 71 SPAIN 73 SWEDEN 76 SWITZERLAND 78 TURKEY 80 UK 84 HUMAN RIGHTS IN EUROPE 3 REVIEW OF 2019 Amnesty International campaigns, harassment, and even In 2019, founding values of the European administrative and criminal penalties. -

Austria's Constitution of 1920, Reinstated in 1945, with Amendments Through 2009

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:54 constituteproject.org Austria's Constitution of 1920, Reinstated in 1945, with Amendments through 2009 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:54 Table of contents Chapter I: General Provisions. European Union . 3 Section A: General Provisions . 3 Section B: European Union . 23 Chapter II: Federal Legislation . 26 Section A: The National Council . 26 Section B: The Federal Council . 29 Section C: The Bundesversammlung. 31 Section D: Federal Legislative Procedure . 31 Section E: Participation of the National Council and of the Federal Council in the Execution by the Federation . 35 Section F: Status of Members of the National Council and the Federal Council . 40 Chapter III: Federal Execution . 43 Section A: Administration . 43 1. The Federal President . 43 2. The Federal Government . 46 3. The Federal Security Authorities . 49 4. The Federal Army . 50 5. The Federal School Authorities . 51 6. Universities . 53 Section B: Jurisdiction . 53 Chapter IV: Legislation and Execution by the Laender . 56 Section A: General Provisions . 56 Section B: The Federal Capital Vienna . 61 Chapter V: Self administration . 62 Section A: municipalities . 62 Section B: Other self administration . 68 Chapter VI: Control of Public Accounts and Administration of Public Funds . 68 Chapter VII: Constitutional and Administrative Guarantees . 74 Section A: Independent Administrative Tribunals in the Laender . 74 Section B: Asylum Court . 75 Section C: The Administrative Court . 76 Section D: The Constitutional Court . 79 Chapter VIII: Ombudsman board . -

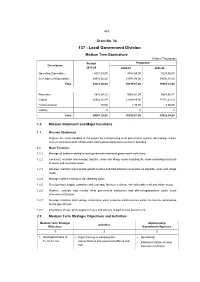

137 - Local Government Division

453 Grant No. 34 137 - Local Government Division Medium Term Expenditure (Taka in Thousands) Budget Projection Description 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22 Operating Expenditure 4321,54,00 4753,69,00 5229,06,00 Development Expenditure 29919,66,00 31541,98,00 34696,18,00 Total 34241,20,00 36295,67,00 39925,24,00 Recurrent 7815,04,16 9003,87,04 8807,80,41 Capital 26425,35,84 27289,84,96 31115,37,59 Financial Asset 80,00 1,95,00 2,06,00 Liability 0 0 0 Total 34241,20,00 36295,67,00 39925,24,00 1.0 Mission Statement and Major Functions 1.1 Mission Statement Improve the living standard of the people by strengthening local government system, developing climate resilient rural and urban infrastructure and implementing socio-economic activities. 1.2 Major Functions 1.2.1 Manage all matters relating to local government and local government institutions; 1.2.2 Construct, maintain and manage Upazilla, union and village roads including the roads and bridges/culverts of towns and municipal areas; 1.2.3 Develop, maintain and manage growth centres and hats-bazaars connected via Upazilla, union and village roads; 1.2.4 Manage matters relating to safe drinking water; 1.2.5 Develop water supply, sanitation and sewerage facilities in climate risk vulnerable rural and urban areas; 1.2.6 Finance, evaluate and monitor local government institutions and offices/organizations under Local Government Division; 1.2.7 Develop, maintain and manage small-scale water resource infrastructures within the timeline determined by the government. 1.2.8 Enactment of Law, promulgation of rules and policies related to local government.