October 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

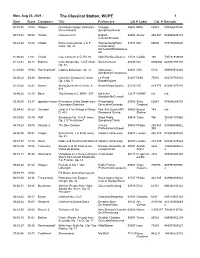

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Mon, Aug 23, 2021 - The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 12:02 Wagner Die Meistersinger: Selections Chicago 05288 BMG 63301 090266330126 (for orchestra) Symphony/Reiner 00:14:3208:54 Handel Concerto in D English 04894 Archiv 453 451 028945345123 Concert/Pinnock 00:24:26 34:44 Chopin Piano Concerto No. 2 in F Weissenberg/Paris 01070 EMI 69036 077776903620 minor, Op. 21 Conservatory Orchestra/Skrowaczew ski 01:00:40 11:01 Vivaldi Lute Concerto in D, RV 93 Isbin/Pacifica Quartet 13728 Cedille 190 735131919029 01:12:4125:17 Brahms Cello Sonata No. 1 in E minor, Mork/Grimaud 07246 DG 0006904 028947757191 Op. 38 01:38:5819:54 Rachmaninoff Caprice bohemien, Op. 12 Vancouver 03341 CBC 5143 059582514320 Symphony/Comissiona 02:00:2209:26 Geminiani Concerto Grosso in C minor, La Petite 01027 DHM 77010 054727701023 Op. 2 No. 5 Bande/Kuijken 02:10:4834:32 Mozart String Quintet In G minor, K. Beyer/Melos Quartet 01130 DG 419 773 028941977328 516 02:46:2012:15 Bach Trio Sonata in C, BWV 1037 Ida & Ani 12237 CMNW n/a n/a Kavafian/McDermott 03:00:0503:37 Ippolitov-Ivanov Procession of the Sardar from Philadelphia 03983 Sony 62647 074646264720 Caucasian Sketches Orchestra/Ormandy Classical 03:04:4256:53 Schubert Octet in F for Strings & Winds, Fine Arts Quartet/NY 04503 Boston 143 n/a D. 803 Woodwind Quintet Skyline 04:03:0535:15 Raff Symphony No. 10 in F minor, Basel Radio 08615 Tudor 786 761991107862 Op. 213 "In Autumn" Symphony/Travis 1 04:39:2009:45 Strauss Jr. -

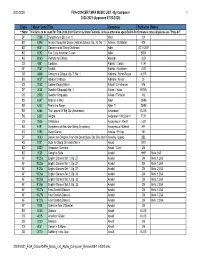

8/11/2020 FOA CONCERT MPA MUSIC LIST - by Composer 1 2020-2021 (Approved 07/23/2020)

8/11/2020 FOA CONCERT MPA MUSIC LIST - By Composer 1 2020-2021 (Approved 07/23/2020) Class Music Code Title Composer Publisher Notes ** Note: This list is to be used for FOA 2020-2021 District & State Festivals. Unless otherwise specified in Performance notes all pieces are "Play All" BF 7066 Symphony in Eb (mvt. 1) Abel OX BS 6346 Ancient Song And Dance (Hebrew Dance, Op. 35, No. 1) Achron / McAllister KM BS 6041 Concertino for String Orchestra Adler SC / OOP BS 6292 Five Early American Tunes Adler BSM AS 8060 Pastoral for Strings Ahrendt LUD CS 4351 Cordoba Albeniz / Lipton FJH BF 7087 Sevilla Albeniz / McAlister LUD CS 4348 Concerto a Cinque, Op. 7, No. 1 Albinoni / Farrar-Royce ALFR BS 6007 Albinoni's Adagio Albinoni / Keiser CF CS 2062 Colonel Bogey March Alford / Christensen KM DF 3038 Swedish Rhapsody No. 1 Alfven / Isaac WYNN CS 2306 Swedish Rhapsody Alfven / Fishburn WJ BS 6347 Birds on a Wire Allen GMM BS 6303 Fire in the Forge Allen, T. GMM BS 6366 The Legend Of Big Ole (Amundson) Amundson KJOS BS 6322 Allegro Anderssen / McCashin FJH CS 2506 Childgrove Anonymous / Atwell LUD BS 6191 Symphonia de Navitate-String Symphony Anonymous / Blahnik API ES 1183 Sword Dance Arbeau / Phillips HE DF 3060 Danse des Ghazies, From the Ballet Suite, Op. 50a: Mvt 9 Arensky / Lopez BEL AS 8101 Suite for String Orchestra No. 5 Ariosti ANY BS 6220 Vespasian Overture Ariosti / Clark LM ES 1023 Campfire Suite Arnold HHP Mvts. 1&3 AF 9125a English Dances Set 1, Op. 27 Arnold CN Mvts. -

EDVARD GRIEG Complete Symphonic Works • Vol. 1

EDVARD GRIEG Complete Symphonic Works Vol. 1 • Symphonic Dances, Op. 64 • Peer Gynt Suite No. 1, Op. 46 incidental music to Peer Gynt by Ibsen • Peer Gynt Suite No. 2, Op. 55 incidental music to Peer Gynt by Ibsen • funeral March in Memory of Rikard Nordraak EG 107 WDR SINfONIEORCHESTER KöLN EIVIND AADLAND, conductor recording date: Oktober 2010 Philharmonie, Köln release date: 24 June 2011 »audite« Ludger Böckenhoff • Tel.: +49 (0) 52 31-870 320 • Fax: +49 (0) 52 31-870 321 • [email protected] • www.audite.de EDVARD GRIeg Complete Symphonic Works Vol. II • Two Elegiac Melodies, Op. 34 • Holberg Suite, Op. 40 • Two Melodies, Op. 53 • Two Nordic Melodies, Op. 63 recording date: August / September 2009 relese date: August 2011 audite 92.579 (SACD / digipac) Vol. III • Concerto in A minor, Op. 16 • Old Norwegian Romance with Variations for orchestra, Op. 51 • Lyric Suite for Orchestra, Op. 54 • “Glockengeläute” recording date: September 2011 / February 2012 audite 92.669 (SACD / digipac) Vol. IV • “I host“ (In Autumn), concert overture for orchestra, Op. 11 • Six Orchestral Songs • Two Lyric Pieces • “Der Bergentrückte“ • Three Orchestral Pieces from Sigurd Jorsalfar, Op.56 audite 92.670 (SACD / digipac) Vol. V • Symphony No. 1 • Norwegian Dances • “Vor der Klosterpforte“ • etc. audite 92.671 (SACD / digipac) WDR Sinfonieorchester Köln Eivind Aadland, conductor »audite« Ludger Böckenhoff • Tel.: +49 (0) 52 31-870 320 • Fax: +49 (0) 52 31-870 321 • [email protected] • www.audite.de PLAYS ON ALL CD- AND SACD- PLAYERS! MUSIKPRODUKTION Press Info: EDVARD GRIEG Complete Symphonic Works • Vol. I • Symphonic Dances, Op. -

Edvard Grieg's Ballade in the Form of Variations on a Norwegian Melody

Edvard Grieg’s Ballade in the Form of Variations on a Norwegian Melody, Op.24, for Piano, and Old Norwegian Melody with Variations, Op.51, for Two Pianos: An Analytical Overview and Interpretive Study of the Variation Procedure D.M.A. Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Amalia Sagona, B.M., M.M. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2009 Document Committee: Steven Glaser, Advisor Kenneth Williams Danielle Fosler-Lussier Copyright by Amalia Sagona 2009 Abstract Edvard Grieg (1843-1907), Norway’s greatest composer of the 19th century, is particularly known as a lyrical composer of songs and piano miniatures. The great majority of his piano works are short character pieces influenced by the Romantic tradition (mostly in three-part form), with a large part of them especially characterized by the use of Norwegian folk and folk-like melodies, harmonies, and rhythms. Grieg’s larger works employing the piano (solo or chamber music) and exploring the sonata form include his Piano Sonata in E Minor, Op.7, a number of chamber music compositions (three Sonatas for Violin and Piano and one Sonata for Cello and Piano), and the most familiar Piano Concerto in A Minor, Op.16. Moreover, his larger-scale piano works include two important essays in the variation form: the Ballade in the Form of Variations on a Norwegian Melody, Op.24, for piano, and the Old Norwegian Melody (Romance) with Variations, Op.51, for two pianos. -

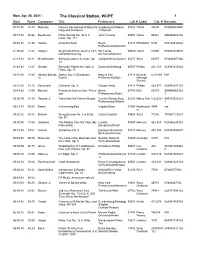

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Mon, Apr 26, 2021 - The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 10:12 Debussy Dances Sacred and Profane for Kondonassis/Oberlin 07989 Telarc 80694 089408069420 Harp and Orchestra 21/Reischl 00:12:4226:56 Beethoven Piano Sonata No. 32 in C John O’Conor 05591 Telarc 80261 089408026126 minor, Op. 111 00:40:38 18:36 Handel Amaryllis Suite Royal 01219 RPO/MCA 6186 076732618622 Philharmonic/Menuhin 01:00:4412:48 Wagner Siegfried's Rhine Journey from Minnesota 05989 Telarc 82005 089408200526 Gotterdammerung Orchestra/Marriner 01:14:32 30:11 Mendelssohn String Quartet in A minor, Op. Juilliard String Quartet 05275 Sony 60579 074646057926 13 01:45:4313:47 Dvorak Romantic Pieces for Violin & Zukerman/Neikrug 00587 Philips 416 158 028941615824 Piano, Op. 75 02:01:00 13:20 Rimsky-Korsak Sadko, Op. 5 (Symphonic Mexico City 01478 Musical 512145A N/A ov Poem) Philharmonic/Batiz Heritage Society 02:15:2031:10 Schumann Carnaval, Op. 9 Claudio Arrau 01411 Philips 420 871 028942087125 02:47:3011:59 Borodin Polovtsian Dances from Prince Berlin 07743 EMI 00273 509995002732 Igor Philharmonic/Rattle 3 03:00:59 16:34 Strauss Jr. Tales from the Vienna Woods Czecho-Slovak State 02381 Marco Polo 8.223221 489103023221 Philharmonic/Wildner 1 03:18:3300:59 Beach A Humming-Bird Virginia Eskin 01568 Northeaste 9004 n/a rn 03:20:32 38:42 Brahms String Quartet No. 3 in B flat, Cavani Quartet 05624 Azica 71216 787867121627 Op. 67 04:00:4413:55 Smetana The Moldau from Ma Vlast (My London 05047 Mercury 462 953 028946295328 Fatherland) Symphony/Dorati 04:15:39 33:01 Hanson Symphony No. -

GRIEG, Edvard Hagerup (1843-1907)

BIS-SACD-1391 SURROUND DSD Recording Total playing time: 74'36 GRIEG, Edvard Hagerup (1843-1907) Sigurd Jorsalfar, Op. 22 (1872) (Edition Peters) 34'31 Incidental music to the play by Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson 1 I. Introduction to Act I. Molto Andante e maestoso 2'10 2 II. Borghild’s Dream. Poco andante – Allegro agitato 3'42 3 III. At the Matching Game. Allegretto semplice 3'38 4 IV. The Northland Folk*°. Allegro moderato e molto energico 5'58 5 V. Homage March. Allegro molto – Allegretto marziale 9'17 6 VI. Interlude I. Allegretto tranquillo 1'45 7 VII. Interlude II. Allegretto marziale – Maestoso 3'34 8 VIII. The King’s Song*. Poco Andante – Vivace – Molto Andante e maestoso 4'07 *Håkan Hagegård, baritone ° Male voices from the Bergen Philharmonic Choir, Seim Songkor and Kor Vest 9 Landkjenning, Op. 31 (1872, rev. 1881) (Edition Peters) 6'30 for baritone, male choir and orchestra. Text: Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson Håkan Hagegård, baritone Male voices from the Bergen Philharmonic Choir, Seim Songkor and Kor Vest 10 Bergliot, Op. 42 (1871, orch. 1885) (Edition Peters) 18'37 Melodrama for declamation and orchestra. Text: Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson Gørild Mauseth, narrator 2 11 Sørgemarsj over Rikard Nordraak, EG 117 (1866) (Edition Peters) 7'49 (arranged for orchestra [1907] by Johan Halvorsen) 12 Den Bergtekne, Op. 32 (1877-78) (Wilhelm Hansen) 5'37 for baritone and orchestra. Text: traditional Norwegian Håkan Hagegård, baritone Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Ole Kristian Ruud The music on this Hybrid SACD can be played back in Stereo as well as in 5.0 Surround sound. -

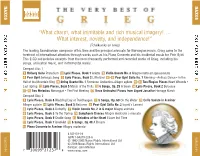

What Charm, What Inimitable and Rich Musical Imagery

NAXOS NAXOS “What charm, what inimitable and rich musical imagery! … What interest, novelty, and independence!” (Tchaikovsky on Grieg) The leading Scandinavian composer of his time and the principal advocate for Norwegian music, Grieg came to the forefront of international attention through works such as his Piano Concerto and his incidental music for Peer Gynt. This 2-CD set includes excerpts from the most frequently performed and recorded works of Grieg, including his songs, orchestral music, and instrumental music. Compact Disc 1 1 Holberg Suite Preludium 2 Lyric Pieces, Book 1 Arietta 3 Violin Sonata No. 3 Allegro molto ed appassionato 4 Peer Gynt Solveig’s Song 5 Lyric Pieces, Book 3 Little Bird 6–8 Peer Gynt Suite No. 1 Morning • Anitra’s Dance • In the Hall of the Mountain King 9 String Quartet No. 1 Romanze: Andantino–Allegro agitato 0–! Two Elegiac Pieces Heart Wounds • Last Spring @ Lyric Pieces, Book 5 March of the Trolls # 6 Songs, Op. 25 A Swan $ Lyric Pieces, Book 2 Berceuse %–^ Two Melodies Norwegian • The First Meeting & Three Orchestral Pieces from Sigurd Jorsalfar Homage March Compact Disc 2 1 Lyric Pieces, Book 8 Wedding Day at Troldhaugen 2 5 Songs, Op. 60 On the Water 3 Cello Sonata in A minor Allegro agitato 4 Lyric Pieces, Book 5 Notturno 5 Peer Gynt Suite No. 2 Ingrid’s Lament 6 Lyric Pieces, Book 3 Butterfly 7 Violin Sonata No. 2 in G major Allegro animato 8 Lyric Pieces, Book 3 To the Spring 9 Symphonic Dances Allegro moderato e marcato 0 Lyric Pieces, Book 9 Cradle Song ! Melodies of the Heart I Love But Thee @ Lyric Pieces, Book 7 Brooklet # 6 Songs, Op.48 A Dream $ Piano Concerto in A minor Allegro moderato 8.552123-24 8.552123-24 8.552123-24 ISBN 1-84379-220-6 ൿ 1990-2003 Naxos Rights International Ltd Ꭿ 2006 Naxos Rights International Ltd Cartoon: John Minnion www.naxos.com. -

Edvard Grieg's Orchestral Style

Bjarte Engeset: EDVARD GRIEG’S ORCHESTRAL STYLE - a conductor’s point of view Good morning, everybody! Edvard Grieg (1843–1907) wrote the following after he had performed his Norwegian Peasant Dances (Slåtter) op. 72: I played them with all my love and all my troll magic. 1 Jeg spillede dem med al den Kjærlighed og Troldskab, jeg ejede. In the written introduction to Slåtter he uses similar word pairs describing the music: «their combination of nice and pure grace with bold power and untamed ferocity».2 In such associative word pairings, close to value-laden concepts like God and Devil, Culture and Barbarism, Grieg reveals his aesthetics. I therefore use this contrastive sentence as disposition for this study of Grieg’s universe of orchestral sonorities: [1] «Love» (Colour) «A World of Sonorities» «The Path of Poetry» «Imbued with the one great Tone» «The transparent Clarity» «This Natural Freshness» «Troll magic» (Contour) «Rhythmical Punctuation» «Brave and bizarre Phantasy» «The Horror and Songs of the Waterfall» These symbol loaded bars from Night Scene in Peer Gynt op. 23, depicts in a condensed way this universe: Example 1: Night Scene (Peer Gynt op. 23), bb. 19–23. [2] Grieg here links very different colours. The first augmented chord is dominated by a stopped horn note marked fp, floating into a soft and bright A-major chord marked pp, with a typical sound of two flutes and two clarinets. We are entering a world rich of associations and contrast. Grieg had a great concern for the element of sound colour, so the lack of research in this particular field is both surprising and motivating. -

Sarah Ioannides Music

1 SARAH IOANNIDES Conductor Pages 1 -11 Works conducted in performance. Pages 11-13 Works prepared as Cover Conductor for the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestral/Instrumental Bach Brandenburg Concertos Nos. 2, 3, 5 Bach, J.C. Sinfonia, Op. 18 No. 1 Bach/Respighi Three Chorale Preludes Balakirev Overture King Lear Barber Adagio for Strings Music for a Scene from Shelley Two movements from the Opera, Vanessa Bartok Concerto for Orchestra Beethoven Contradances Coriolan Overture Egmont Overture Fidelio Overture Creatures of Prometheus Overture Symphony Nos. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 (arr. Cooper) Berlioz Symphonie Fantastique Bernstein Candide Overture On The Waterfront Symphonic Suite Three Dances from On The Town West Side Story Selections (arr. Mason) Symphonic Dances from West Side Story Suite No.2 from West Side Story Bizet L’Arlesienne Suite No. 2 Carmen Suites No. 1 & 2 Symphony in C Bliss Music for Strings Bloch Epic Rhapsody “America” Finale Borodin In the Steppes of Central Asia Polovtsian Dances (with choir) L Boulanger D’un matin de printemps Brahms Symphony Nos. 1, 2 & 4 Tragic Overture Haydn Variations Hungarian Dances Nos. 1 & 5 Britten Four Sea Interludes Simple Symphony Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra Chabrier Espana Chadwick Euterpe Copland Appalachian Spring Suite El Salon Mexico (2015-16 season) Fanfare for the Common Man Debussy La Mer Prelude à l’apres midi d’un faune Three Nocturnes Dukas Sorcerer’s Apprentice Dvorak Symphony Nos. 7, 8 & 9 In Nature’s Realm Noon Witch www.sarahioannides.net 9/23/19 2 SARAH IOANNIDES Conductor Elgar Enigma Variations (also prepared Symphony No. -

School of Music Faculty of Fine Arts University of Victoria C

School of Music Faculty of Fine Arts University of Victoria C MUS UNIVERSITY OF VICTORIA Orchestra Nordic Light With Muzi Xu, piano soloist UVic Concerto Competition Winner Studio of Arthur Rowe Ajtony Csaba, Conductor Friday, October 28, 2016 • 8:00 p.m. University Centre Farquhar Auditorium University of Victoria Adults: $20 / Seniors: $15 / Students & UVic alumni: $10 P R O G R A M From Holberg’s Time “Suite in olden style” Op. 40 Edvard Grieg Introduction (1843–1907) Matthew Sabo, Undergraduate conductor Air Rigaudon Oberon Overture Carl Maria von Weber (1786–1826) Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 16 Edvard Grieg Allegro molto moderato Adagio Allegro moderato molto e marcato—Quasi presto— Andante maestoso Soloist: Muzi Xu, piano I N T E R M I S S I O N Serenade for Winds, Op. 7 Richard Strauss (1864–1949) Peer Gynt Suites Edvard Grieg No. 2, Op. 55 i. Der Brautraub No. 1, Op. 46 i. Morning Mood iv. In the Hall of the Mountain King Symphonic Dances, Op. 64 Edvard Grieg Allegro Moderato e marcato Allegretto grazioso—Più mosso Allegro giocoso Andante—Allegro molto e risoluto BIOGRAPHIES Muzi Xu, piano At the young age of 3, Muzi Xu started to play the piano and instantly enjoyed per- forming in front of others. Coupled with the full support of her family, she gradually developed a keen interest in music. Now, music is an integral part of her life and she has continued playing the piano on a daily basis for nearly 15 years. Muzi has partici- pated in various piano competitions and music festivals and was first-prize winner of the Yamaha Piano Competition when she was in elementary school. -

Two Orchestral Embodiments of Three Pieces from Op. 54 by Edvard Grieg Dve Orkestrski Realizaciji Treh Skladb Iz Op

R. URNIEŽIUS • TWO ORCHESTRAL EMBODIMENTS... UDK 785Grieg E.:78.083.1Lirična suita:781.63 DOI: 10.4312/mz.56.1.101-132 Rytis Urniežius Univerza v Šiauliai, Litva Šiauliai University, Lithuania Two Orchestral Embodiments of Three Pieces from op. 54 by Edvard Grieg Dve orkestrski realizaciji treh skladb iz op. 54 Edvarda Griega Prejeto: 30. maj 2019 Received: 30th May 2019 Sprejeto: 28. april 2020 Accepted: 28th April 2020 Ključne besede: Edvard Grieg, Lirična suita, Keywords: Edvard Grieg, Lyric Suite, orchestration orkestracija IZVLEČEK ABSTRACT Lirična suita je orkestrska verzija štirih stavkov iz Lyric Suite is an orchestral version of four move- Griegovih Liričnih skladb V, op. 54. Trije od teh šti- ments from Grieg’s Lyric Pieces V, op. 54. Three out rih stavkov obstajajo v dveh orkestrskih različicah. of these four movements exist in two orchestral ver- Cilj pričujoče raziskave je izpostaviti edinstvene sions. The aim of the current research is to highlight lastnosti Griegovega orkestrskega sloga v poznem peculiar traits of Grieg’s orchestral style in the late obdobju skladateljevega življenja, in sicer s primer- period of composer’s life by comparing scores of javo teh dveh orkestracij. two orchestrators. 101 MZ_2020_1_FINAL.indd 101 24. 06. 2020 12:00:38 MUZIKOLOŠKI ZBORNIK • MUSICOLOGICAL ANNUAL LVI/1 Introduction Lyric Suite and Old Norwegian Melody with variations, op. 51 are the last two orches- tral works by Edvard Grieg. Lyric Suite is an orchestral version of four movements from Grieg’s Lyric Pieces V, op. 54. Three out of these four movements (“Norwegian March”, “Notturno”, and “March of the Dwarfs”) are the subject of the comparative analysis de- livered in the current article. -

Danse Macabre

TRILLS & CHILLSII 2018.19 MILWAUKEE SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA TEACHER RESOURCE GUIDE 2 Welcome! Table of Contents On behalf of the musicians and staff of the Milwaukee Symphony Welcome from Director of Education................ 2 Orchestra, I am pleased to welcome you to our 2018.19 education Audio Guide Information ........................... season. We are thrilled to have you and your students come to 3 our concerts. It will be a fun, educational, and engaging musical Have Fun with the MSO............................. 4 experience. MSO Biography .................................... 5 To help prepare your students to hear this concert, you will find About the Conductor .............................. 6 key background information and activities for all of the featured musical selections and their composers. Additionally, three Program ........................................... 7 pieces are presented in the Comprehensive Musicianship though Program Notes . 8 Performance model. These pieces have skill, knowledge and affective outcomes, complete with strategies and assessments. It Resources ........................................ 29 is our hope that you will find this guide to be a valuable tool in Glossary.......................................... 31 preparing your students to hear and enjoy Trills & Chills II About the MSO Education Department ...........34 Special thanks to Forte, the MSO Volunteer League, for their volunteer support of MSO Education initiatives. We thank the 2018.19 Orchestra Roster .........................35 docents and