Edvard Grieg's Ballade in the Form of Variations on a Norwegian Melody

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs for Piano Alone a Look at Franz Liszt’S Buch Der Lieder Für Piano Allein Books I and Ii

SONGS FOR PIANO ALONE A LOOK AT FRANZ LISZT’S BUCH DER LIEDER FÜR PIANO ALLEIN BOOKS I AND II BY JEREMY RAFAL Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University December, 2012 Accepted by the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music __________________________________ Karen Shaw, Chairperson __________________________________ Edmund Battersby, Committee Member __________________________________ Emile Naoumoff, committee member ii Songs for Piano Alone A Look at Franz Liszt’s Buch der Lieder für Piano allein Books I and II Music circles have often questioned the artistic integrity of piano transcriptions: should they should be on the same par as “original works” or are they merely imitations of somebody else’s work? Franz Liszt produced hundreds of piano transcriptions of works by other composers making him one of the leading piano transcriptionists of all time. While transcriptions are the results of rethinking and remolding pre-existing materials, how should we view the “transcriptions” of the composer’s own original work? Liszt has certainly taken much of his original non-piano works and transcribed them for solo piano. But would these really be transcriptions, or different versions? This thesis explores the question of how transcriptions of Liszt’s own works should be treated, particularly the solo piano pieces in the two books of Buch der Lieder für Piano allein. While some pieces are clearly transcriptions of previous art songs, some pieces should really be characterized as independent piano pieces first before art songs. -

The Year's Music

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com fti E Y LAKS MV5IC 1896 juu> S-q. SV- THE YEAR'S MUSIC. PIANOS FOR HIRE Cramer FOR HARVARD COLLEGE LIBRARY Pianos BY All THE BEQUEST OF EVERT JANSEN WENDELL (CLASS OF 1882) OF NEW YORK Makers. 1918 THIS^BQQKJS FOR USE 1 WITHIN THE LIBRARY ONLY 207 & 209, REGENT STREET, REST, E.C. A D VERTISEMENTS. A NOVEL PROGRAMME for a BALLAD CONCERT, OR A Complete Oratorio, Opera Recital, Opera and Operetta in Costume, and Ballad Concert Party. MADAME FANNY MOODY AND MR. CHARLES MANNERS, Prima Donna Soprano and Principal Bass of Royal Italian Opera, Covent Garden, London ; also of 5UI the principal ©ratorio, dJrtlustra, artii Sgmphoiu) Cxmctria of ©wat Jfvitain, Jtmmca anb Canaba, With their Full Party, comprising altogether Five Vocalists and Three Instrumentalists, Are now Booking Engagements for the Coming Season. Suggested Programme for Ballad and Opera (in Costume) Concert. Part I. could consist of Ballads, Scenas, Duets, Violin Solos, &c. Lasting for about an hour and a quarter. Part II. Opera or Operetta in Costume. To play an hour or an hour and a half. Suggested Programme for a Choral Society. Part I. A Small Oratorio work with Chorus. Part II. An Operetta in Costume; or the whole party can be engaged for a whole work (Oratorio or Opera), or Opera in Costume, or Recital. REPERTOIRE. Faust (Gounod), Philemon and Baucis {Gounod) (by arrangement with Sir Augustus Harris), Maritana (Wallace), Bohemian Girl (Balfe), and most of the usual Oratorios, &c. -

Peer Gynt: Suite No. 1 Instrumentation: Piccolo, 2 Flutes, 2 Oboes, 2

Peer Gynt: Suite No. 1 Instrumentation: piccolo, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, strings. Duration: 15 minutes in four movements. THE COMPOSER – EDVARD GRIEG (1843-1907) – Grieg spent much of the 1870s collaborating with famous countrymen authors. With Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson, the composer had hoped to mount a grand operatic history of King Olav Tryggvason but the two artists soon ran afoul of one another. A possible contributing factor was Grieg’s moonlighting project with Henrik Ibsen but, in truth, Bjørnson and the composer had been nursing hurt feelings for a while by the time the latter began to stray. THE MUSIC – As it turned out, Grieg’s back-up plan was more challenging than rewarding at first. He was to compose incidental music that expanded and stitched together the sections of Ibsen’s epic poem. This he did with delight, but soon found the restrictions of the theatrical setting more a burden than a help creatively. “In no case,” he claimed, “had I opportunity to write as I wanted” but the 1876 premiere was a huge success regardless. Grieg seized the chance to re-work some of the music and add new segments during the 1885 revival and did the same in 1902. The two suites he published in 1888 and 1893 likely represent his most ardent hopes for his part of the project and stand today as some of his most potently memorable work. Ibsen’s play depicted the globetrotting rise and fall of a highly symbolic Norwegian anti-hero and, in spite of all the aforementioned struggles, the author could not have chosen a better partner than Grieg to enhance the words with sound. -

Introduction to the Art of Drum Circle Facilitation, Part 4 Facilitating the Drum Ensemble Towards Orchestrational Consciousness by Arthur Hull

INTRODUCTION TO THE ART OF DRUM CIRCLE FACILITATION, PART 4 FACILITATING THE DRUM ENSEMBLE TOWARDS ORCHESTRATIONAL CONSCIOUSNESS BY ARTHUR HULL his is the fourth in a series of five articles and video in- cilitator is to help the players use their notes to make space for Tstallments that describe and demonstrate the four stages other people’s creativity. of the Village Music Circles Drum Circle Facilitation Protocol. 3. Melody Line. Once you have your players listening and By using this VMC protocol, you will be able to take a circle talking to each other in their interactive rhythmical dialogue, of drummers from a group playing consciousness to an en- you have set the foundation for a particular melody line, or semble playing consciousness, and finally into orchestration- Rhythm Song, to appear in the totality of the group’s interactive al consciousness, where drum rhythm grooves are turned into playing. These melody lines in your drum circle group’s playing music. will constantly evolve and change throughout the event. Sculpt- If you have been following this series of articles, you have ing and showcasing the particular players who are the funda- gone through the basic Village Music Circle protocol that will mental contributors of any “dialogue melody line” is the key to help you get a drum circle started through facilitating interac- facilitating your playing group into higher and more sophisticat- tive experiential rhythmical playing actives. I have introduced ed forms of musicality. to you the process of facilitating a “Drum Call” experience that will educate your drum circle playing group about itself and the collaborative musical potential that exists in any group rhythm event. -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

Editing Historical Music in the Age of Digitization

Editing Historical Music in the Age of Digitization Jørgen Langdalen The National Library of Norway Author Jørgen Langdalen is a senior researcher at The National Library of Norway, where he takes part in the preparation of the new Johan Svendsen Edition. Langdalen was trained as a music historian at The University of Oslo, where he earned his PhD with a dissertation on Gluck and Rousseau. Abstract Norwegian Musical Heritage—a program for preserving, editing and publishing historical music from Norway—benefits from digitization programs like that of The National Library of Norway. Digital media, in turn, opens new possibilities in the publication of historical music editions on the Internet. In both cases we see that digital technology draws new attention to the historical documents serving as sources of music edition. Although digitization strips them of their material form, they gain tremendously in virtual visibility. This visibility may contribute to a shift in critical edition, away from a predominant concern for the need to reach a single unequivocal reading, toward a greater interest for the real diversity of the sources. This broadened perspective may moderate the canonizing effect associated with traditional editions and open a more spacious field of interpretation and experience. In this way, more people may take part in the formation of cultural repertoires, in a media situation where such repertoires are no longer provided by traditional institutions, venues and media. 1. Introduction This paper presents a new initiative for preserving, editing and publishing historical music from Norway, called Norwegian Musical Heritage. The aim of the program is to make historical music available for performance and research in Norway and abroad. -

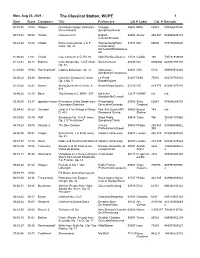

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Mon, Aug 23, 2021 - The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 12:02 Wagner Die Meistersinger: Selections Chicago 05288 BMG 63301 090266330126 (for orchestra) Symphony/Reiner 00:14:3208:54 Handel Concerto in D English 04894 Archiv 453 451 028945345123 Concert/Pinnock 00:24:26 34:44 Chopin Piano Concerto No. 2 in F Weissenberg/Paris 01070 EMI 69036 077776903620 minor, Op. 21 Conservatory Orchestra/Skrowaczew ski 01:00:40 11:01 Vivaldi Lute Concerto in D, RV 93 Isbin/Pacifica Quartet 13728 Cedille 190 735131919029 01:12:4125:17 Brahms Cello Sonata No. 1 in E minor, Mork/Grimaud 07246 DG 0006904 028947757191 Op. 38 01:38:5819:54 Rachmaninoff Caprice bohemien, Op. 12 Vancouver 03341 CBC 5143 059582514320 Symphony/Comissiona 02:00:2209:26 Geminiani Concerto Grosso in C minor, La Petite 01027 DHM 77010 054727701023 Op. 2 No. 5 Bande/Kuijken 02:10:4834:32 Mozart String Quintet In G minor, K. Beyer/Melos Quartet 01130 DG 419 773 028941977328 516 02:46:2012:15 Bach Trio Sonata in C, BWV 1037 Ida & Ani 12237 CMNW n/a n/a Kavafian/McDermott 03:00:0503:37 Ippolitov-Ivanov Procession of the Sardar from Philadelphia 03983 Sony 62647 074646264720 Caucasian Sketches Orchestra/Ormandy Classical 03:04:4256:53 Schubert Octet in F for Strings & Winds, Fine Arts Quartet/NY 04503 Boston 143 n/a D. 803 Woodwind Quintet Skyline 04:03:0535:15 Raff Symphony No. 10 in F minor, Basel Radio 08615 Tudor 786 761991107862 Op. 213 "In Autumn" Symphony/Travis 1 04:39:2009:45 Strauss Jr. -

Christianialiv

Christianialiv Works from Norway’s Golden Age of wind music Christianialiv The Staff Band of the Norwegian Armed Forces The second half of the 19th century is often called the “Golden Age” of Norwegian music. The reason lies partly in the international reputations established by Johan Svendsen and Edvard Grieg, but it also lies in the fact that musical life in Norway, at a time of population growth and economic expansion, enjoyed a period of huge vitality and creativity, responding to a growing demand for music in every genre. The Staff Band of the Norwegian Armed Forces (to use its modern name) played a key role in this burgeoning musical life not just by performing music for all sections of society, but also by discovering and fostering musical talent in performers and composers. Johan Svendsen, Adolf Hansen, Ole Olsen and Alfred Evensen, whose music we hear on this album, can therefore be called part of the band’s history. Siste del av 1800-tallet er ofte blitt kalt «gullalderen» i norsk musikk. Det skyldes ikke bare Svendsens og Griegs internasjonale posisjon, men også det faktum at musikklivet i takt med befolkningsøkning og økonomiske oppgangstider gikk inn i en glansperiode med et sterkt behov for musikk i alle sjangre. I denne utviklingen spilte Forsvarets stabsmusikkorps en sentral rolle, ikke bare som formidler av musikkopplevelser til alle lag av befolkningen, men også som talentskole for utøvere og komponister. Johan Svendsen, Adolf Hansen, Ole Olsen og Alfred Evensen er derfor en del av korpsets egen musikkhistorie. The Staff Band of the Norwegian Armed Forces / Ole Kristian Ruud Recorded in DXD 24bit/352.8kHz 5.1 DTS HD MA 24/192kHz 2.0 LPCM 24/192kHz + MP3 and FLAC EAN13: 7041888519027 q e 101 2L-101-SABD made in Norway 20©14 Lindberg Lyd AS 7 041888 519027 Johan Svendsen (1840-1911) Symfoni nr. -

MAHANI TEAVE Concert Pianist Educator Environmental Activist

MAHANI TEAVE concert pianist educator environmental activist ABOUT MAHANI Award-winning pianist and humanitarian Mahani Teave is a pioneering artist who bridges the creative world with education and environmental activism. The only professional classical musician on her native Easter Island, she is an important cultural ambassador to this legendary, cloistered area of Chile. Her debut album, Rapa Nui Odyssey, launched as number one on the Classical Billboard charts and received raves from critics, including BBC Music Magazine, which noted her “natural pianism” and “magnificent artistry.” Believing in the profound, healing power of music, she has performed globally, from the stages of the world’s foremost concert halls on six continents, to hospitals, schools, jails, and low-income areas. Twice distinguished as one of the 100 Women Leaders of Chile, she has performed for its five past presidents and in its Embassy, along with those in Germany, Indonesia, Mexico, China, Japan, Ecuador, Korea, Mexico, and symbolic places including Berlin’s Brandenburg Gate, Chile’s Palacio de La Moneda, and Chilean Congress. Her passion for classical music, her local culture, and her Island’s environment, along with an intense commitment to high-quality music education for children, inspired Mahani to set aside her burgeoning career at the age of 30 and return to her Island to found the non-profit organization Toki Rapa Nui with Enrique Icka, creating the first School of Music and the Arts of Easter Island. A self-sustaining ecological wonder, the school offers both classical and traditional Polynesian lessons in various instruments to over 100 children. Toki Rapa Nui offers not only musical, but cultural, social and ecological support for its students and the area. -

Agosto-Setembro

GIANCARLO GUERRERO REGE O CONCERTO PARA PIANO EM LÁ MENOR, DE GRIEG, COM O SOLISTA DMITRY MAYBORODA RECITAIS OSESP: O PIANISTA DMITRY MAYBORODA APRESENTA PEÇAS DE CHOPIN E RACHMANINOV FABIO MARTINO É O SOLISTA NO CONCERTO Nº 5 PARA PIANO, DE VILLA-LOBOS, SOB REGÊNCIA DE EDIÇÃO CELSO ANTUNES Nº 5, 2014 TIMOTHY MCALLISTER INTERPRETA A ESTREIA LATINO-AMERICANA DO CONCERTO PARA SAXOFONE, DE JOHN ADAMS, COENCOMENDA DA OSESP, SOB REGÊNCIA DE MARIN ALSOP OS PIANISTAS BRAD MEHLDAU E KEVIN HAYS APRESENTAM O PROGRAMA ESPECIAL MODERN MUSIC RECITAIS OSESP: JEAN-EFFLAM BAVOUZET, ARTISTA EM RESIDÊNCIA 2014, APRESENTA PEÇAS PARA PIANO DE BEETHOVEN, RAVEL E BARTÓK MÚSICA NA CABEÇA: ENCONTRO COM O COMPOSITOR SERGIO ASSAD O QUARTETO OSESP, COM JEAN-EFFLAM BAVOUZET, APRESENTA A ESTREIA MUNDIAL DE ESTÉTICA DO FRIO III - HOMENAGEM A LEONARD BERNSTEIN, DE CELSO LOUREIRO CHAVES, ENCOMENDA DA OSESP ISABELLE FAUST INTERPRETA O CONCERTO PARA VIOLINO, DE BEETHOVEN, E O CORO DA OSESP APRESENTA TRECHOS DE ÓPERAS DE WAGNER, SOB REGÊNCIA DE FRANK SHIPWAY CLÁUDIO CRUZ REGE A ORQUESTRA DE CÂMARA DA OSESP NA INTERPRETAÇÃO DA ESTREIA MUNDIAL DE SONHOS E MEMÓRIAS, DE SERGIO ASSAD, ENCOMENDA DA OSESP COM SOLOS DE NATAN ALBUQUERQUE JR. A MEZZO SOPRANO CHRISTIANNE STOTIJN INTERPRETA CANÇÕES DE NERUDA, DE PETER LIEBERSON, SOB REGÊNCIA DE LAWRENCE RENES MÚSICA NA CABEÇA: ENCONTRO COM O COMPOSITOR CELSO LOUREIRO CHAVES JUVENTUDE SÔNICa – UM COMPOSITOR EM Desde 2012, a Revista Osesp tem ISSN, BUSCA DE VOZ PRÓPRIA um selo de reconhecimento intelectual JOHN ADAMS 4 e acadêmico. Isso significa que os textos aqui publicados são dignos de referência na área e podem ser indexados nos sistemas nacionais e AGO ago internacionais de pesquisa. -

Autumn/Winter Season 2021 Concerts at the Bridgewater Hall Music Director Sir Mark Elder Ch Cbe a Warm Welcome to the Hallé’S New Season!

≥ AUTUMN/WINTER SEASON 2021 CONCERTS AT THE BRIDGEWATER HALL MUSIC DIRECTOR SIR MARK ELDER CH CBE A WARM WELCOME TO THE HALLÉ’S NEW SEASON! We are all thrilled to be able to welcome everyone back to The Bridgewater Hall once more for a full, if shortened, Hallé autumn season. As we glimpse normality again, we can, together, look forward to some magnificent music-making. We will announce our spring concerts in October, but until then there are treasures to be discovered and wonderful stories to be told. Many of you will look forward to hearing some of the repertoire’s great masterpieces, heard perhaps afresh after so long an absence. We particularly look forward to performing these works for people new to our concerts, curious and keen to experience something special. 2 THE HALLÉ’S AUTUMN/WINTER SEASON 2021 AT THE BRIDGEWATER HALL My opening trio of programmes includes Sibelius’s ever-popular Second Symphony, Elgar’s First – given its world premiere by the Hallé in 1908 – and Brahms’s glorious Third, tranquil and poignant, then dramatic and peaceful once more. Delyana Lazarova, our already acclaimed Assistant Conductor, will perform Dvoˇrák’s ‘New World’ Symphony and Gemma New will conduct Copland’s euphoric Third, with its finale inspired by the composer’s own Fanfare for the Common Man. You can look forward to Mussorgsky’s Pictures from an Exhibition, in Ravel’s famous arrangement, Nicola Benedetti playing Wynton Marsalis’s Violin Concerto, Boris Giltburg performing Rachmaninov’s Fourth Piano Concerto, Natalya Romaniw singing Richard Strauss’s Four Last Songs and Elisabeth Brauß playing Grieg’s wonderfully Romantic Piano Concerto. -

April 2021 Vol.22, No. 4 the Elgar Society Journal 37 Mapledene, Kemnal Road, Chislehurst, Kent, BR7 6LX Email: [email protected]

Journal April 2021 Vol.22, No. 4 The Elgar Society Journal 37 Mapledene, Kemnal Road, Chislehurst, Kent, BR7 6LX Email: [email protected] April 2021 Vol. 22, No. 4 Editorial 3 President Sir Mark Elder, CH, CBE Ballads and Demons: a context for The Black Knight 5 Julian Rushton Vice-President & Past President Julian Lloyd Webber Elgar and Longfellow 13 Arthur Reynolds Vice-Presidents Diana McVeagh Four Days in April 1920 23 Dame Janet Baker, CH, DBE Some notes regarding the death and burial of Alice Elgar Leonard Slatkin Relf Clark Sir Andrew Davis, CBE Christopher Robinson, CVO, CBE Book reviews 36 Andrew Neill Arthur Reynolds, Relf Clark Martyn Brabbins Tasmin Little, OBE CD Reviews 44 Christopher Morley, Neil Mantle, John Knowles, Adrian Brown, Chairman Tully Potter, Andrew Neill, Steven Halls, Kevin Mitchell, David Morris Neil Mantle, MBE DVD Review 58 Vice-Chairman Andrew Keener Stuart Freed 100 Years Ago... 60 Treasurer Kevin Mitchell Peter Smith Secretary George Smart The Editors do not necessarily agree with the views expressed by contributors, nor does the Elgar Society accept responsibility for such views. Front Cover: Portrait photograph of Longfellow taken at ‘Freshfields’, Isle of Wight in 1868 by Julia Margaret Cameron. Courtesy National Park Service, Longfellow Historical Site. Notes for Contributors. Please adhere to these as far as possible if you deliver writing (as is much Editorial preferred) in Microsoft Word or Rich Text Format. Copyright: it is the contributor’s responsibility to be reasonably sure that copyright permissions, if required, are obtained. Professor Russell Stinson, the musicologist, in his chapter on Elgar in his recently issued Bach’s Legacy (reviewed in this issue) states that Elgar had ‘one of the greatest minds in English music’.1 Illustrations (pictures, short music examples) are welcome, but please ensure they are pertinent, This is a bold claim when considering the array of intellectual ability in English music ranging cued into the text, and have captions.