The Anglo-American Commercial Aviation Rivalry, 1939-45

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Airline Schedules

Airline Schedules This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on January 08, 2019. English (eng) Describing Archives: A Content Standard Special Collections and Archives Division, History of Aviation Archives. 3020 Waterview Pkwy SP2 Suite 11.206 Richardson, Texas 75080 [email protected]. URL: https://www.utdallas.edu/library/special-collections-and-archives/ Airline Schedules Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Series Description .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 5 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 6 - Page 2 - Airline Schedules Summary Information Repository: -

British Imperial Policy and the Indian Air Route, 1918-1932

British Imperial Policy and the Indian Air Route, 1918-1932 CROMPTON, Teresa Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/24737/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version CROMPTON, Teresa (2014). British Imperial Policy and the Indian Air Route, 1918- 1932. Doctoral, Sheffield Hallam Universiy. Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk British Imperial Policy and the Indian Air Route, 1918-1932 Teresa Crompton A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Sheffield Hallam University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 2014 Abstract The thesis examines the development of the civil air route between Britain and India from 1918 to 1932. Although an Indian route had been pioneered before the First World War, after it ended, fourteen years would pass before the route was established on a permanent basis. The research provides an explanation for the late start and subsequent slow development of the India route. The overall finding is that progress was held back by a combination of interconnected factors operating in both Britain and the Persian Gulf region. These included economic, political, administrative, diplomatic, technological, and cultural factors. The arguments are developed through a methodology that focuses upon two key theoretical concepts which relate, firstly, to interwar civil aviation as part of a dimension of empire, and secondly, to the history of aviation as a new technology. -

BOAC Staff Towards 650+ for Website.Pub

Poole Flying Boats Celebration (Charity No.1123274) PFBC Archive: Our Charity is committed to developing & maintaining its Public -Access Archive… For the purpose of this website a brief selection of items together with information have been provided where references in blue indicate further material is available. Á Part Nineteen … ‘ BOAC Staff at Poole: Towards 650+ ’… (IAL 1939 and BOAC 1940 -48) © PFBC (Staff employed at Poole with IAL & then BOAC in WW2, through to the postwar era ) It is reckoned that during the era 1939 -1948, firstly with Imperial Airways Ltd. (IAL) when relocated to Poole Harbour, and then British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC), members of some 650+ local families in Poole & Bournemouth were employed as Staff to provide the facilities focussed upon Poole’s Marine Terminal for the Civil -Air Flying Boat ops. This included members of the Marinecraft Unit which was essential to provide the links between the Moorings & Quays: During WW2 with many of the MCU Men enlisted in the Royal Navy or to serve elsewhere, a significant shortage arose, whereon 18 Women were recruited to train as Seamen , at a School set up by BOAC at Poole expressly as replacements ! As well as the 650+ employees ( - some based here throughout the period) there were a further 50+ members of the MCU belonging to the Ministry of Civil Aviation (MCA) who operated pinnaces, fire floats, control launches and patrol craft. Besides the shore -based Staff and the Marinecraft Unit, IAL /BOAC had a significant number of Aircrew based at Poole: With the Fall of France, plus the entry of Italy into the War and the closure of the Mediterranean Sea for the time being, a Detachment of support Staff, including maintenance engineers from Hythe etc., and aircrew left for Durban, S. -

The Impacts of Globalisation on International Air Transport Activity

Global Forum on Transport and Environment in a Globalising World 10-12 November 2008, Guadalajara, Mexico The Impacts of Globalisation on International Air Transport A ctivity Past trends and future perspectives Ken Button, School of George Mason University, USA NOTE FROM THE SECRETARIAT This paper was prepared by Prof. Ken Button of School of George Mason University, USA, as a contribution to the OECD/ITF Global Forum on Transport and Environment in a Globalising World that will be held 10-12 November 2008 in Guadalajara, Mexico. The paper discusses the impacts of increased globalisation on international air traffic activity – past trends and future perspectives. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS NOTE FROM THE SECRETARIAT ............................................................................................................. 2 THE IMPACT OF GLOBALIZATION ON INTERNATIONAL AIR TRANSPORT ACTIVITY - PAST TRENDS AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVE .................................................................................................... 5 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 5 2. Globalization and internationalization .................................................................................................. 5 3. The Basic Features of International Air Transportation ....................................................................... 6 3.1 Historical perspective ................................................................................................................. -

Neil Cloughley, Managing Director, Faradair Aerospace

Introduction to Faradair® Linking cities via Hybrid flight ® faradair Neil Cloughley Founder & Managing Director Faradair Aerospace Limited • In the next 15 years it is forecast that 60% of the Worlds population will ® live in cities • Land based transportation networks are already at capacity with rising prices • The next transportation revolution faradair will operate in the skies – it has to! However THREE problems MUST be solved to enable this market; • Noise • Cost of Operations • Emissions But don’t we have aircraft already? A2B Airways, AB Airlines, Aberdeen Airways, Aberdeen Airways, Aberdeen London Express, ACE Freighters, ACE Scotland, Air 2000, Air Anglia, Air Atlanta Europe, Air Belfast, Air Bridge Carriers, Air Bristol, Air Caledonian, Air Cavrel, Air Charter, Air Commerce, Air Commuter, Air Contractors, Air Condor, Air Contractors, Air Cordial, Air Couriers, Air Ecosse, Air Enterprises, Air Europe, Air Europe Express, Air Faisal, Air Ferry, Air Foyle HeavyLift, Air Freight, Air Gregory, Air International (airlines) Air Kent, Air Kilroe, Air Kruise, Air Links, Air Luton, Air Manchester, Air Safaris, Air Sarnia, Air Scandic, Air Scotland, Air Southwest, Air Sylhet, Air Transport Charter, AirUK, Air UK Leisure, Air Ulster, Air Wales, Aircraft Transport and Travel, Airflight, Airspan Travel, Airtours, Airfreight Express, Airways International, Airwork Limited, Airworld Alderney, Air Ferries, Alidair, All Cargo, All Leisure, Allied Airways, Alpha One Airways, Ambassador Airways, Amber Airways, Amberair, Anglo Cargo, Aquila Airways, -

Air Transport

The History of Air Transport KOSTAS IATROU Dedicated to my wife Evgenia and my sons George and Yianni Copyright © 2020: Kostas Iatrou First Edition: July 2020 Published by: Hermes – Air Transport Organisation Graphic Design – Layout: Sophia Darviris Material (either in whole or in part) from this publication may not be published, photocopied, rewritten, transferred through any electronical or other means, without prior permission by the publisher. Preface ommercial aviation recently celebrated its first centennial. Over the more than 100 years since the first Ctake off, aviation has witnessed challenges and changes that have made it a critical component of mod- ern societies. Most importantly, air transport brings humans closer together, promoting peace and harmo- ny through connectivity and social exchange. A key role for Hermes Air Transport Organisation is to contribute to the development, progress and promo- tion of air transport at the global level. This would not be possible without knowing the history and evolu- tion of the industry. Once a luxury service, affordable to only a few, aviation has evolved to become accessible to billions of peo- ple. But how did this evolution occur? This book provides an updated timeline of the key moments of air transport. It is based on the first aviation history book Hermes published in 2014 in partnership with ICAO, ACI, CANSO & IATA. I would like to express my appreciation to Professor Martin Dresner, Chair of the Hermes Report Committee, for his important role in editing the contents of the book. I would also like to thank Hermes members and partners who have helped to make Hermes a key organisa- tion in the air transport field. -

Speedbird : the Complete History of Boac Pdf, Epub, Ebook

SPEEDBIRD : THE COMPLETE HISTORY OF BOAC PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Robin Higham | 512 pages | 15 Jul 2013 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9781780764627 | English | New York, United Kingdom Speedbird : The Complete History of BOAC PDF Book Wartime Routes and Services Chapter 3. A logical answer would be that this one was already in use, but BOAC obviously used 'blocks' of registrations so surely this one would have been included. Spitfire Manual The order was again changed the following year into just 15 standard and 30 Super VC10s. Colour lithograph. By the airline was doing well carrying 1. The suitcases are made from high gloss vulcanised fibreboard with a metallic sheen for a pearlescent white shimmer, which is complemented by Navy leather trim on the corners and handles. The History Teacher's Handbook. Avbryt Send e-post. Seller Inventory xxbeb Published by AuthorHouseUK Not you? As with many of life's endeavours the three most important aspects are 'timing', 'timing' and 'timing'. The two airlines in Britain operating the VC10 have every reason to be grateful not only for the prestige they enjoy through flying this aircraft in their colours but also for the undoubted attraction it has for passengers. Seller Inventory N02L Negative Horizon is Paul Virilio's most original and unified exploration of the key themes and Franco via Aviation Photography of Miami collection. Moreover it includes guidance in a number of fields in which no similar source is available By clicking "That's OK" below, or continuing to use the site, you confirm your agreement to this use. British Overseas Airways Corporation -- Posters. -

Imperial Airways Limited 1924 – 1940

IMPERIAL AIRWAYS LIMITED 1924 – 1940 Talk and display given to The Collectors Club of New York 3rd October 2012 Barry Scott FRPSL Auckland, New Zealand Introduction This collection has been built up over a period of some twenty – five years and started life as an exhibit of New Zealand commercial air mails. Over a period of years in has developed into the display that you see before you, that of Imperial Airways Limited. I am interested in commercially flown air mails and how the Air line developed the air mail system to take into account the vast distances imposed by the extended British Empire and the wishes of the British Government at the time of the Air line’s inception. It is a work in progress and over the years has had some very interesting items added to it and this has continued to this day, with a number of longstanding gaps being filled only recently in the past two or three months. Again recently I have been lucky enough to acquire original Post Office documents to support the beginnings of the “Empire Air Mail Scheme” to various parts of the Empire. These documents together with original documents produced by the Air line have helped to establish with accuracy when and where the Air line and its staff of dedicated people ensured that the air routes were expanded in a logical fashion. My primary interest in the air mails is not so much the advent of first flight covers, but rather the commercial mails that prove that the mails continued to be flown over certain routes, whilst others required detailed descriptions as to how the mails got to their destinations via such and such a routing is not always clear. -

Theyre Lee Elliott

Theyre Lee-Elliott Graphic Designer and Artist, 1903-1988 Glenn H Morgan FRPSL I have always had an interest in the stylised artwork of the 1930s-era and no- one captured that style for me more than graphic artist Theyre Lee-Elliott, especially his GPO work that incorporated letter boxes. Unfortunately, it has proved very difficult to obtain a biography about this man, but I will be actively pursuing this in a more vigorous manner shortly. His best remembered creation is probably that of the Imperial Airways “Speedbird” logo design. This was used by Imperial between 1932-1939 and later continued in use through to 1973 by successor BOAC. The design still looks modern today despite being almost three-quarters of a century old and could so easily have just been submitted by a design agency to an airline undergoing a current rebranding exercise. He published at least one book, entitled Paintings of the Ballet*, a subject that he first painted in 1936. This had an introduction by Arnold Haskell and included a selection of his drawings and paintings, recapturing the mood and magical spirit of the original performances, apparently delighting all lovers of the ballet. I am aware of just the few items illustrated on the following pages that were created for the General Post Office of the 1930s, but other gems may well lie hidden in the archives of the British Postal Museum & Archive in London. Unfortunately, their search engine reveals nothing of relevance. The opportunity has been taken to also show here other works by him that I have traced through searches on the internet. -

British Airways Profile

SECTION 2 - BRITISH AIRWAYS PROFILE OVERVIEW British Airways is the world's second biggest international airline, carrying more than 28 million passengers from one country to another. Also, one of the world’s longest established airlines, it has always been regarded as an industry-leader. The airline’s two main operating bases are London’s two main airports, Heathrow (the world’s biggest international airport) and Gatwick. Last year, more than 34 million people chose to fly on flights operated by British Airways. While British Airways is the world’s second largest international airline, because its US competitors carry so many passengers on domestic flights, it is the fifth biggest in overall passenger carryings (in terms of revenue passenger kilometres). During 2001/02 revenue passenger kilometres for the Group fell by 13.7 per cent, against a capacity decrease of 9.3 per cent (measured in available tonne kilometres). This resulted in Group passenger load factor of 70.4 per cent, down from 71.4 per cent the previous year. The airline also carried more than 750 tonnes of cargo last year (down 17.4 per cent on the previous year). The significant drop in both passengers and cargo carried was a reflection of the difficult trading conditions resulting from the weakening of the global economy, the impact of the foot and mouth epidemic in the UK and effects of the September 11th US terrorist attacks. An average of 61,460 staff were employed by the Group world-wide in 2001-2002, 81.0 per cent of them based in the UK. -

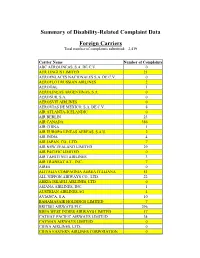

Summary of Disability-Related Complaint Data Foreign Carriers Total Number of Complaints Submitted: 2,419

Summary of Disability-Related Complaint Data Foreign Carriers Total number of complaints submitted: 2,419 Carrier Name Number of Complaints ABC AEROLINEAS, S.A. DE C.V. 0 AER LINGUS LIMITED 21 AEROENLACES NACIONALES S.A. DE C.V. 0 AEROFLOT RUSSIAN AIRLINES 2 AEROGAL 1 AEROLINEAS ARGENTINAS, S.A. 0 AEROSUR, S.A. 0 AEROSVIT AIRLINES 0 AEROVIAS DE MEXICO, S.A. DE C.V. 8 AIR ATLANTA-ICELANDIC 0 AIR BERLIN 23 AIR CANADA 386 AIR CHINA 1 AIR EUROPA LINEAS AEREAS, S.A.U. 2 AIR INDIA 4 AIR JAPAN, CO., LTD. 7 AIR NEW ZEALAND LIMITED 29 AIR PACIFIC LIMITED 0 AIR TAHITI NUI AIRLINES 3 AIR TRANSAT A.T., INC. 7 AIRES 0 ALITALIA COMPAGNIA AEREA ITALIANA 51 ALL NIPPON AIRWAYS CO., LTD. 22 ARKIA ISRAELI AIRLINES, LTD. 0 ASIANA AIRLINES, INC. 1 AUSTRIAN AIRLINES AG 4 AVIANCA, S.A. 10 BAHAMASAIR HOLDINGS LIMITED 7 BRITISH AIRWAYS PLC 296 BWIA WEST INDIES AIRWAYS LIMITED 17 CATHAY PACIFIC AIRWAYS LIMITED 34 CAYMAN AIRWAYS LIMITED 0 CHINA AIRLINES, LTD. 0 CHINA EASTERN AIRLINES CORPORATION 0 COMLUX MALTA LTD. 0 COMPANIA MEXICANA DE AVIACION, S.A. 0 COMPANIA PANAMENA DE AVIACION, S.A. 10 CONDOR FLUGDIENST GMBH 0 CORSAIR 0 DC AVIATION GMBH 0 DEUTSCHE LUFTHANSA AG 215 EGYPTAIR 0 EL AL ISRAEL AIRLINES LTD. 56 EMIRATES 28 ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES ENTERPRISE 0 ETIHAD AIRWAYS P.J.S.C. 0 EUROATLANTIC AIRWAYS TRANSPORTES AE 0 EVA AIRWAYS CORPORATION 1 FINNAIR OY D/B/A FINNAIR OYJ 0 FIRST AIR 0 GLOBAL JET LUXEMBOURG S.A. 0 HAINAN AIRLINES COMPANY LTD 0 HELLENIC IMPERIAL AIRWAYS 0 IBERIA LINEAS AEREAS DE ESPANA, S.A 65 IBERWORLD AIRLINES, S.A. -

Emirates Airline, Etihad Airways and Qatar Airways Global Airline Companies Promoting the International Position and Reputation of Dubai, Abu Dhabi and Qatar

Études de l’Ifri EMIRATES AIRLINE, ETIHAD AIRWAYS AND QATAR AIRWAYS Global Airline Companies Promoting the International Position and Reputation of Dubai, Abu Dhabi and Qatar Julien LEBEL July 2019 Turkey and Middle East Program The Institut français des relations internationales (Ifri) is a research center and a forum for debate on major international political and economic issues. Headed by Thierry de Montbrial since its founding in 1979, Ifri is a non-governmental, non-profit organization. As an independent think tank, Ifri sets its own research agenda, publishing its findings regularly for a global audience. Taking an interdisciplinary approach, Ifri brings together political and economic decision-makers, researchers and internationally renowned experts to animate its debate and research activities. The opinions expressed in this text are the responsibility of the author alone. ISBN: 979-10-373-0046-1 © All rights reserved, Ifri, 2019 How to cite this publication: Julien Lebel, « Emirates Airline, Etihad Airways and Qatar Airways: Global Airline Companies Promoting the International Position and Reputation of Dubai, Abu Dhabi and Qatar », Études de l’Ifri, Ifri, July 2019. Ifri 27 rue de la Procession 75740 Paris Cedex 15 – FRANCE Tél. : +33 (0)1 40 61 60 00 – Fax : +33 (0)1 40 61 60 60 Email : [email protected] Website: Ifri.org Author Julien Lebel holds a Ph.D. in geography from the French Institute of Geopolitics (Institut français de géopolitique - IFG) at the Université Paris 8. His research centers on civil aviation and especially on how political actors use air routes to gain influence and promote their interests at various geographic levels.